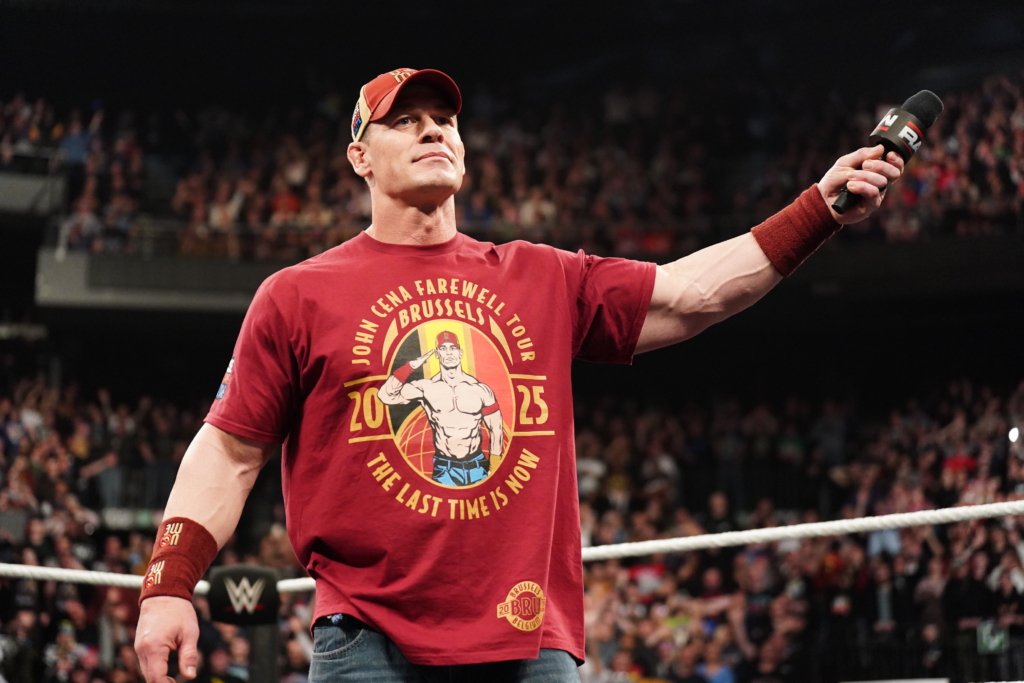

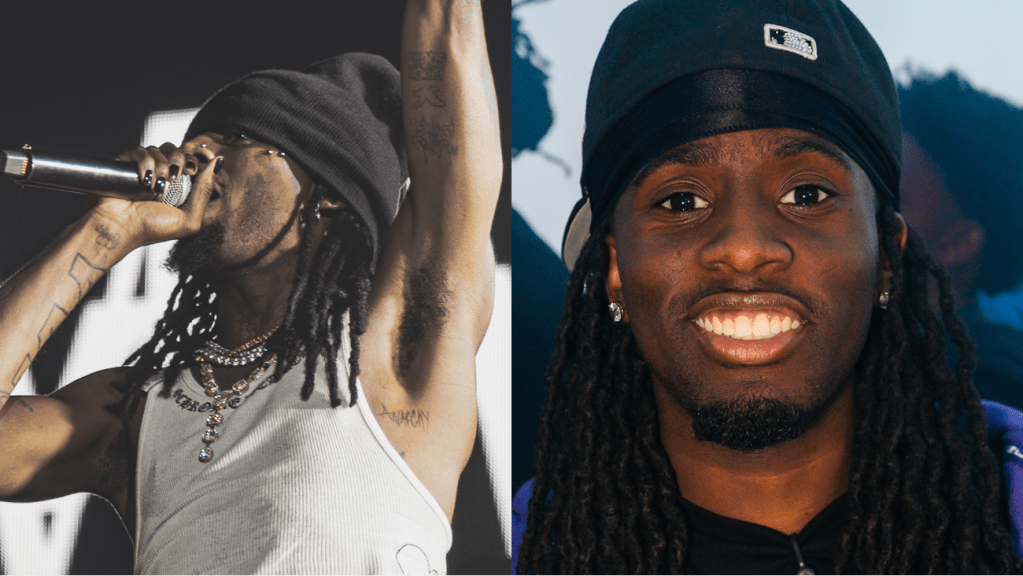

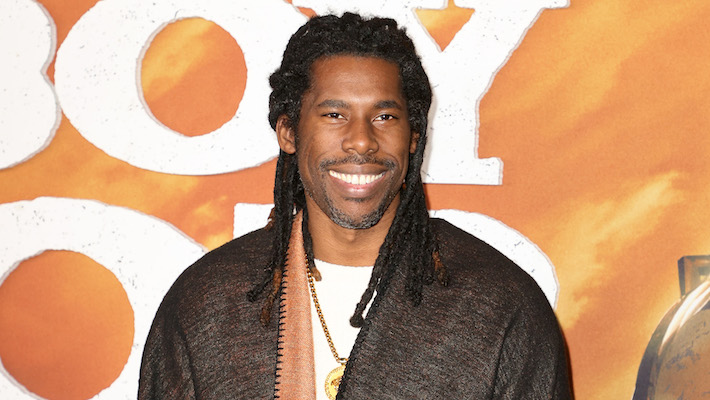

Workforce: ‘Nothing Iz Scared’ – and that’s the point

Workforce returns with ‘Nothing Iz Sacred’ – an LP that both embraces and pushes against the evolving landscape of drum & bass. Released on his own imprint, Must Make Music, it delivers eight tracks that sit at the typical 174 BPM, but veer into some atypical sounds and production – all while subtly challenging the constraints […]

Workforce returns with ‘Nothing Iz Sacred’ – an LP that both embraces and pushes against the evolving landscape of drum & bass. Released on his own imprint, Must Make Music, it delivers eight tracks that sit at the typical 174 BPM, but veer into some atypical sounds and production – all while subtly challenging the constraints of modern music consumption.

This project marks a shift from his 2022 album ‘Set & Setting’, which was deeply considered, interwoven with interludes, and sculpted during lockdowns when clubs were closed. Now, in a post-COVID world, Jack Stevens is a father, a seasoned label owner, and an artist with less time for overthinking and over-tinkering. There’s no meticulous sequencing here, no endless tweaking – just raw, focused expression, free from self-imposed perfectionism.

That mindset fuels the title, ‘Nothing Iz Sacred’ – a reflection on how streaming, algorithmic curation, and even AI-generated music have reshaped listeners’ relationships with art. Music doesn’t linger like it used to. In the interview, Stevens recalls ‘The View’ by LSB, DRS & Tyler Daley as the last drum & bass track to truly resonate across the entire scene. Can a track still do that today? If any from this project could, it’s Falling Down – a soulful collaboration with Tyler Daley and pianist Ed Zuccollo, born from a chance encounter and stitched together in an organic, instinctive way.

The LP as a whole is a masterclass in balance – abrasion and groove, rawness and warmth, structure and spontaneity, and a dark tension held throughout. Guest vocals from Bobbie Johnson and Tamara Blessa lavishly reinforce the moody foundations, while Leroy Horns returns to infuse the record with textured brass. And while this project is more direct than its predecessor, the LP format still gives Stevens room to explore ideas beyond what would fit on a single or EP – rewarding those who engage with his music on a deeper level.

While ‘Nothing Iz Sacred’ embraces creative freedom, it also reflects Stevens’ shifting perspective on what success means in 2025. In an era where streams often dictate an artist’s trajectory, he remains focused on deeper connections – both with listeners and with the artists he supports through his label. He’s selective about his releases and his approach to events – and he’s got no interested in chasing trends. As the interview reveals, this isn’t about playing the DSP game – it’s about making music that hopefully resonates beyond the moment.

Last time UKF spoke with you, it was about ‘Set & Setting’ in 2022. How has life been since then?

I put so much into ‘Set & Setting’ that I struggled to find the energy to dive back into the studio afterward. I’m not someone who likes to rinse and repeat what I’ve done before – there’s always going to be a core DNA to my music since it’s all within drum & bass, but I want each project to feel fresh.

After ‘Set & Setting’, I worked on the ‘Echoes’ project, which was essentially a collection of tracks that didn’t quite make the album. Once that was out, I hit a bit of a creative block – there was a lot going on, like moving studios and just life in general.

This new album, though, kind of came together naturally. I wasn’t overthinking it; the ideas just started flowing again. Having my son nearly a year ago has also been a huge motivator – it’s made me much more focused with the time I have. Most of the music was finished before he was born, and since then, it’s been about finding the right moments to handle the artwork and animation in between everything else.

It sounds like completely different ways of making albums. ‘Set & Setting’ you were locked in a room basically, whereas ‘Nothing Iz Sacred’ feels a bit more like… a healthy headspace, would you say?

I think they’re just different. When I was making ‘Set & Setting’, it started in 2020, and it came out in 2022. There were no clubs at the time, so I just wrote whatever I wanted, with no external pressure.

Because there were no gigs, I could work nights, Monday to Friday, and just treat it like a regular creative process – go in, make music, and see what happened. COVID was a strange time, but in some ways, it gave me the freedom to experiment. Since I’m self-employed, I was eligible for government subsidies, plus I could still sell merch, so financially, I was comfortable enough to focus purely on creativity.

This new album, though, was a different challenge. A big part of that was adjusting back to normality – clubs were open again, gigs were happening, and the landscape had shifted. But also, ‘Set & Setting’ felt like my first true Workforce album. Even though I’d done longer projects before, like the ‘Late Night Soundtrack’ and ‘Your Moves’ on Exit, this was the first one where I consciously tried to build a full album – interludes, themes, and a cohesive journey.

By the time it was done, I was totally drained. I’d put everything into it, and stepping away from the ideas that consumed me during that period felt strange, almost sad, because I’d been so invested in them. After an album like that, it’s hard not to feel exhausted and unsure about what comes next.

So this project felt less exhausting than Set & Setting?

Not really – I don’t think it’s about exhaustion as much as intent. This one just came together naturally. But at the same time, there are tracks on it that wouldn’t exist if I didn’t work on long-form projects. Or maybe they would exist, but they wouldn’t necessarily get released.

There’s a certain type of weird music I enjoy making that just doesn’t work as a standalone single. If I were only releasing singles, those tracks would never see the light of day. So in that sense, the album format feels necessary – it allows me to showcase a broader spectrum of what I like to create.

Did writing an album give you more freedom to experiment, rather than focusing on singles that need to stand out?

With this project, and others more recently, I’ve been trying not to overthink. My natural tendency is to overanalyze everything, but you can’t always think your way out of creative challenges. ‘Set & Setting’ was exhausting because it was so considered and meticulous, but I’m proud of the result. That said, it took a toll – on my energy, my mental health, even my ability to interact with people. I pushed myself too hard.

Now, I still love making music, but I’m trying to find a better balance. Maybe at some point, I’ll feel like diving into another exhaustive, conceptual project, but right now, I just want to write music across a broad spectrum and put it together in a longer format – without it needing to feel like a front-to-back album experience. It’s more like what I did with ‘Late Night Soundtrack’ – a collection of tracks that work together but still stand individually.

I guess I just approached this one differently. Or maybe I didn’t think about it at all.

Your last album had clear statements woven throughout – whether literally or thematically. This one seems to have that too. Can you talk about the message behind it?

Yeah, I think a big part of my frustration after ‘Set & Setting’ was that I put so much into it, but I’m at odds with a culture that doesn’t really foster or appreciate long-form projects like albums. There are obviously people who do, but on the whole, we’ve been conditioned to consume music in a way that’s more transient. Stuff comes out, disappears, and doesn’t really connect with people on a deeper level.

I don’t know if that’s just the nature of DSPs or something bigger, but there’s definitely a shift in how music is valued. There’s a Rick Rubin quote that resonated with me – he talks about how artistic expression isn’t something that can be judged as ‘right’ or ‘wrong’. It’s just a reflection of the artist, like a diary entry. That idea runs through the album. It’s still just drum & bass, but I like weaving in broader concepts and letting them sit there subtly, rather than making an overly pointed statement.

The title ‘Nothing Iz Sacred’ is a reflection of that throwaway culture. And that’s why I asked when this interview is going out – because a week before the album drops, I’m releasing an alternate version called the ‘Distorted Unlistenable Version’. It’s the entire album, but completely destroyed – distorted beyond recognition, to the point where it sounds awful.

Interesting…

It’s basically a comment on how music is treated. If platforms, consumers, and even artists don’t respect music as an art form, then why not just put out trash? Why not deliver something in a format that reflects how disposable everything has become? It’s not even me saying that’s objectively true – it’s more of a provocation. A reminder that people can engage with music on a deeper level, and that behind every track, there’s an artist making something personal. And as we move into an era where AI-generated music is being slipped into playlists, that connection is going to get even worse.

So yeah, I just thought, fuck it – let’s do it. My distributor asked if we should go through with it, and I was like, yeah, why not? Even if it just sparks conversation, that’s the point. It’ll drop out of nowhere – no announcement – just this wrecked, unlistenable version of the album appearing on DSPs. People will ask questions, wonder why it’s there.

Guerilla marketing?

I guess, but not in a cynical way. If I’m going to talk about things being disposable and sacred, what better way to provoke that conversation than by releasing something deliberately trash?

It feels like every artist I’ve spoken to in the past year has faced the same dilemma – do I release an album? Do I adhere to Spotify and social media, or reject it completely? Where do I sit on that spectrum?

Yeah, that’s exactly it – everyone’s playing someone else’s game.

I actually wrote something about this recently: It’s a response to the inertia of music. A reflection of an industry that prioritizes volume over value, where human creativity is sidelined by algorithms churning out lifeless slop – cheapening our societal relationship to art and threatening real artists’ livelihoods.

So the idea is, if you push that to the limit – if you deliberately make something sound like trash – it becomes a reflection of the way music is treated. Trash begets trash.

Yeah, and this whole shift of art and music becoming ‘content’ feels problematic. Things come out, people have a fleeting relationship with them, and then they’re gone.

Exactly. It’s like music has been absorbed into the broader content machine, which just means it’s disposable. Tracks come out, people connect with them briefly, but then they disappear.

I can’t even remember the last tune that truly grabbed everyone – that actually resonated in a lasting way. Maybe ‘The View’ by DRS, Tyler Daley, and LSB – that’s the last one I can think of from my world that still carries real emotional weight, years later.

What does success look like for this album? Is it about streams, purchases, or something else entirely?

Success changes depending on the day. Some days, it’s just writing a tune I really enjoyed making, regardless of whether it performs well commercially. I’ve had tracks where I know they won’t do anything in terms of streams or sales, but for me, they were still a success. If even a small group of people appreciate the full breadth of what I do, that means something.

For me, it’s about security – the ability to keep making the music I want, without being boxed in by numbers. But it’s easy to get caught up in it. You check Spotify stats and think, Oh, that track did well – should I make more like that? And that feedback loop isn’t good.

Spotify, for example, always favors liquid drum & bass over harder tracks. I’ve seen artists outside of D&B blow up because one song got added to big playlists, often with passive listeners – people who just have it on in the background, like on a ‘bath time’ playlist or something. Suddenly, that artist shifts their whole sound to chase that audience. But are you reaching actual fans, or just people who listen passively? Spotify doesn’t differentiate between an engaged fan and someone who’s half-listening while scrolling their phone.

So yeah, success is hard to pin down – it’s always shifting.

That algorithm-driven approach to music feels like part of that ‘enshittification’.

Yeah, there are a few things at play. Part of it is just how people’s behavior has changed – the way we consume media in general. I’m not immune to it either. The constant dopamine hits from scrolling, the way social media rewires our attention spans – it’s all connected.

I saw something recently about Netflix telling screenwriters to make sure characters say what they’re doing in every scene, so people watching with their phones out can still follow along without paying full attention. That blows my mind. We’re being conditioned to accept sloppy, low-effort content as the norm.

I don’t want to sound like I’m just complaining – I actually feel quite optimistic. My goal is to keep pushing, to keep things interesting, and to avoid dumbing it down into the kind of disposable slop that algorithms encourage. If I can keep that connection with fans who actually care about the music, that’s what matters most.

Yeah, it comes from a place of wanting it to do well.

And wanting better for the culture.

Exactly – this [drum & bass and music in general] is your life, it’s our lives.

Yeah, I’m a huge fan of Stewart Lee. I don’t know if you’ve ever watched his stand-up, but he’s probably the most successful comedian in the UK that no one’s heard of. Instead of doing the O2, he’ll do Leicester Square Theatre for 100 nights straight.

His comedy is really meta – he deconstructs what he’s doing while he’s doing it, breaking the crowd into groups: some people who get the joke, some who don’t, and some who are just confused. It’s abstract and deliberately challenging.

That aspect of his work really resonates with me – the idea that art doesn’t just have to be palatable, it can push the audience a little too. It still delivers on its core purpose – people laugh, they enjoy the show – but at the same time, they’re being prodded and engaged on a deeper level.

Obviously, I know I’m just making drum & bass – I’m not pretending it has the same effect as stand-up comedy. But it does give me the opportunity to have interesting discussions and experiment with ideas, like dropping a completely distorted version of my album. Why not push things a bit?

Do you see boutique labels like yours, Gemini Gemini, Rubi Records, and the like, as pushing against some of these trends?

Yeah, I think by their nature, they have to. Ultimately, it’s artists saying, I just want to do my own thing – to have complete creative control without being beholden to anyone else.

Running your own label gives you the purest, most unfiltered platform for expression. You’re handling the art, the schedule, the A&R – it’s entirely on your terms. I was talking to someone about this recently, and there’s a huge freedom in that. But at the same time, sometimes you do wish there was someone there to say, “this tune is done – put it out as it is”.

I think we’re all at risk of playing the DSP game to some extent, but I also work with a distributor that’s open to trying things differently, which helps. The key is remembering that DSPs aren’t the be-all and end-all. I see them as a shop window, not the whole business model. They exist somewhere between radio and direct sales – it’s not as simple as give me your money, here’s your product.

With boutique labels, I think Alix Perez has set the perfect example. He’s built a strong brand with 1985 Music – consistent, high-quality releases, never straying off-brand. He’s created a real pathway for fans to discover the music, become hardcore supporters, attend events, and eventually buy the merch.

I don’t mean this in a negative way, but it’s almost tribal – not in a cultish sense, but in the way he’s built a true community around the 1985 sound. That’s what makes it so powerful. It’s not just a label – it’s an ecosystem that people want to be part of, whether as fans or artists. That’s what I see as an alternative to the more disposable, algorithm-driven side of the industry.

Totally agree about 1985. How is Must Make going? You had Azifm on the label – do you have more releases coming up from other artists?

Yeah, after this album, I’ve got two releases lined up from other artists. I won’t say who just yet – one of them is quite unexpected and outside the box – but this year, I definitely want to release more music from other people.

When I started Must Make, I never intended it to be a label for other artists – it was just a platform for me, kind of like how Calibre started Signature. But when I heard Azifm’s music, I couldn’t not release it. It was too good. From there, it snowballed, and I started realizing that I actually enjoy working with artists.

That said, I’m not the type of label head who wants to micromanage. I don’t like heavy-handed A&R – when I was releasing on other labels, I never liked that myself. My approach is more about helping artists get the best out of their music rather than pushing them in a certain direction.

For example, I’m working with an artist right now who was finishing an EP but felt like he was one track short. Instead of forcing something to fit, I just said, Why not take a risk? Try something different – don’t worry about making a dancefloor track. He went away and made this incredible experimental drum & bass tune, something really different for him. That’s the kind of environment I want to foster.

I don’t have some big grand plan for the label – it’s all about the music presenting itself naturally. If I hear something I love, and the artist is someone I genuinely vibe with, then I want to support it. These days, I find myself caring just as much about who I work with as I do about the music itself. I’d rather release a solid tune from a good person I respect than a massive track from someone I’ve never met and don’t connect with. I don’t know why, but that’s just how I’ve come to approach things.

Exciting times for the label, even if you’re taking things as they come.

Yeah, and Azifm has a big project in the works. He relocated to Melbourne after spending some time in the UK, and we’re working on something bigger for him now. His music really lends itself to a larger project – he’s got a distinct sound, but he’s also branching out into different tempos and styles. Hopefully, it’ll come together by the end of the year, but we’re still working out the timing.

‘Falling Down’ is an obvious stand-out from the project. How did this one come together?

That track started with a pianist named Ed Zucollos, who I met at Northern Bass years ago. He’s a Kiwi musician, a bit of a legend out there. He was posting these piano clips online, and it turned out his family lived just around the corner from me in Worthing – crazy coincidence. A few years ago, we did some sessions together, recording a bunch of piano, but nothing came of it at the time.

Fast-forward to this album – I knew I wanted to work with Tyler, so I hit up Ed, and he sent me a load of stems. I found a loop I liked, built the track around it, and it all came together super quickly.

Love these encounters. How about the rest of the album coming together production-wise?

There was definitely more freedom on this record. Some tracks came together naturally, without me pulling them apart too much. On ‘Set & Setting’, I was hyper-focused on arrangement, trying to create these intricate structures. You hear it in Kendrick [Lamar] albums – where he’ll throw in a completely different section in the middle of a track before snapping back to the original groove.

With this album, ‘Deep Ones’ was probably my most indulgent track in that sense. It started as a simple club tune – just drums, bass, and some bleeps. But then I got Leroy Horns, the saxophonist from ‘Set & Setting’, to lay down parts, and that’s when it really evolved. I added key changes, small extra bars here and there – little details to break up the structure.

I hadn’t really thought about any of this until you asked, but yeah – this album was much more about going on feel rather than obsessively planning everything. That was probably a reaction to how much I overthought ‘Set & Setting’. With that record, I could explain every single decision, every structure, every transition. This time, there was intention behind what I did, but I wasn’t constantly analysing it.

It’s all drum & bass, but it really has a sonic uniqueness to it.

That’s definitely a conscious choice – maybe to a fault. I never want my music to sound too similar to anyone else’s. But at the same time, it still has to sit within the framework of drum & bass. It’s a balance.

With ‘How They See It’, for example, I wanted to take the energy and sonics of modern jump-up and present it in a more underground way. Some people have even messaged me calling it ‘tasteful foghorn’, ha, which I’ll take as a compliment. That was the idea – capturing that energy but presenting it differently.

What’s next? Anything for the label, or Workforce?

For Must Make, I’ve got a couple of releases lined up from other artists over the next few months. Some bigger projects are coming, including more from Azifm.

Personally, I’ve actually got a lot of new music ready to go this year – unlike after Set & Setting, where I had nothing lined up. I’ve been working on a project with LSB, which might turn into a proper collab release. I’ve also done remixes for Halogenix and LSB – LSB’s will be out on the ‘Annotations’ V/A later in March.

Beyond that, I’ve got a remix for Bobbie Johnson, the rapper from ‘Deep Ones’. She’s got some really cool music that I might help with this year. And I’m currently working on a track with DRS, which is sounding really tight – I was working on it right before this call.

For gigs, I’m being selective. I’ve got Bass Coast in Canada, which I’m really excited about. But with a young son at home, I’m prioritising quality over quantity. I want to focus more on the studio than chasing every festival slot.

![‘Karma’ – Netflix’s Korean Thriller Series Stars ‘Squid Game’ Actor Park Hae-Soo [Trailer]](https://bloody-disgusting.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/Karma_unit_104_B_A03554_cr-scaled.jpg)

![Underwater FPS ‘Chasmal Fear’ Surfaces on Steam April 17 [Trailer]](https://bloody-disgusting.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/chasmal.jpg)

![Inside the Vault [on SPIONE]](http://img.youtube.com/vi/gOltBk-9-rU/0.jpg)

![Please Watch Carefully [THE HEART OF THE WORLD]](http://www.jonathanrosenbaum.net/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/the-heart-of-the-world-5-300x166.jpg)

![Passenger Pops Open Champagne Mid-Flight—That Didn’t Go Over Quietly [Roundup]](https://viewfromthewing.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/passenger-pops-champagne.jpg?#)

.jpg?width=1920&height=1920&fit=bounds&quality=80&format=jpg&auto=webp#)

![[Podcast] Should Brands Get Political? The Risks & Rewards of Taking a Stand with Jeroen Reuven Bours](https://justcreative.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/jeroen-reuven-youtube-1.png)

![[Podcast] Should Brands Get Political? The Risks & Rewards of Taking a Stand with Jeroen Reuven](https://justcreative.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/jeroen-reuven-youtube.png)