What It’s Really Like to Travel to Iraq as a Westerner Right Now

A new film sheds light on perception vs reality.

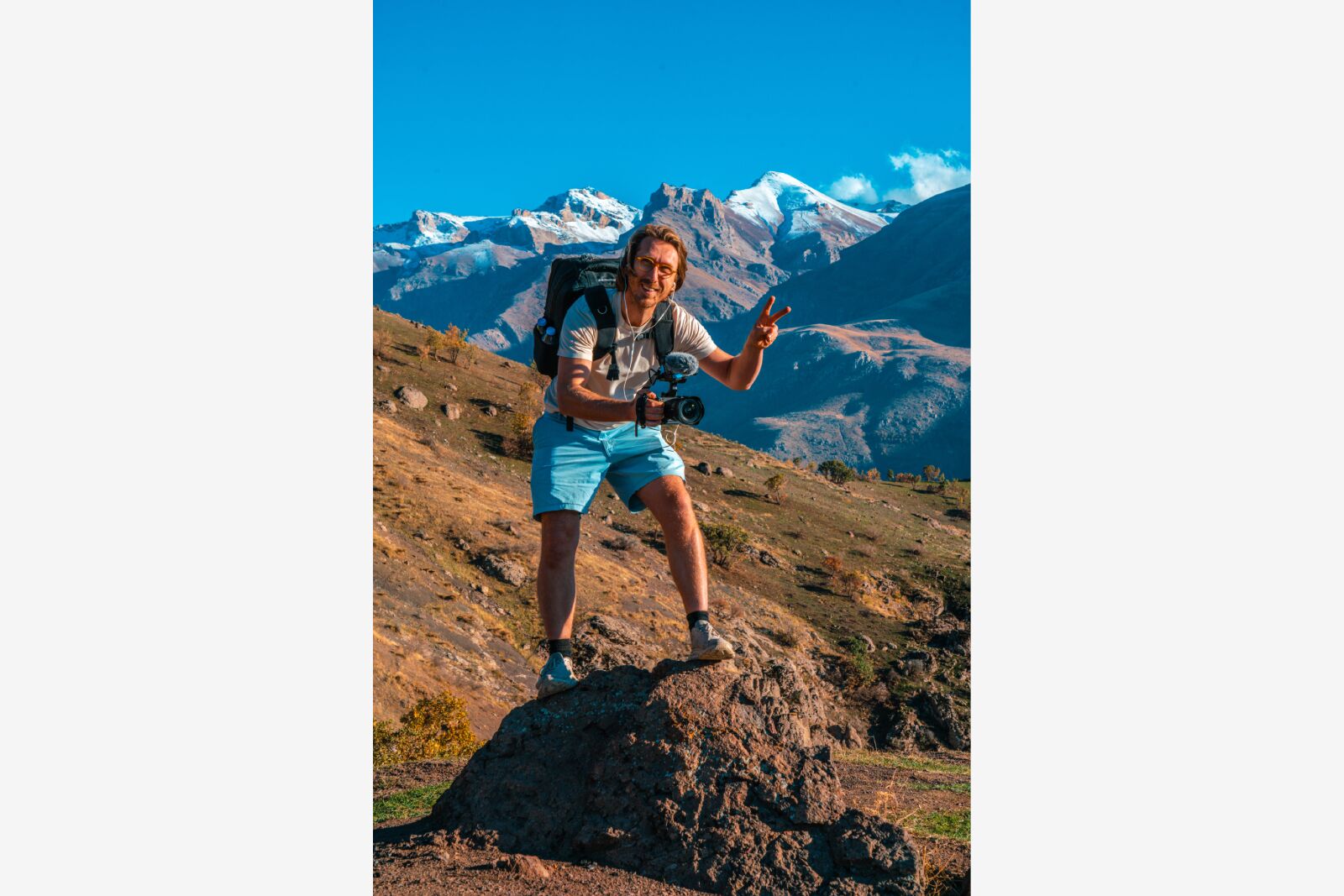

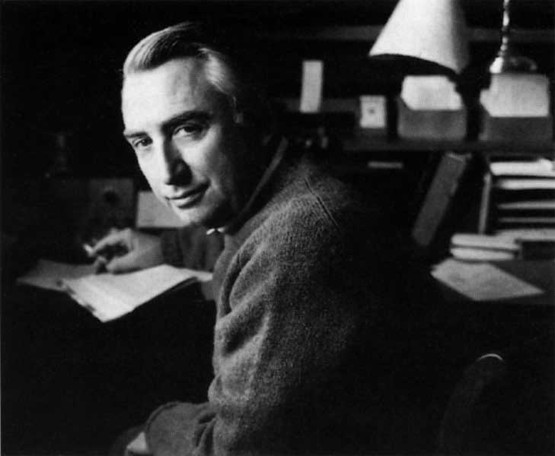

In a world where headlines often paint countries in broad strokes, Dutch filmmaker Reinier van Oorsouw wants to offer an alternative — particularly in places many Westerners wouldn’t typically consider visiting. His latest film, produced in partnership with Matador Network, is an exploration of Iraq.

“Our perception of the world is very different than reality,” van Oorsouw says. Traveling to places not typically popular with Western tourists is an opportunity for cultural understanding, rather than just a touristic experience. It’s all about nuance, he says, including nuance in risk assessment. “You can never eliminate a risk,” he adds. But if you can book a car for a road trip relatively easily, finding accommodations on the go, that passes van Oorsouw’s internal evaluation of what’s safe.

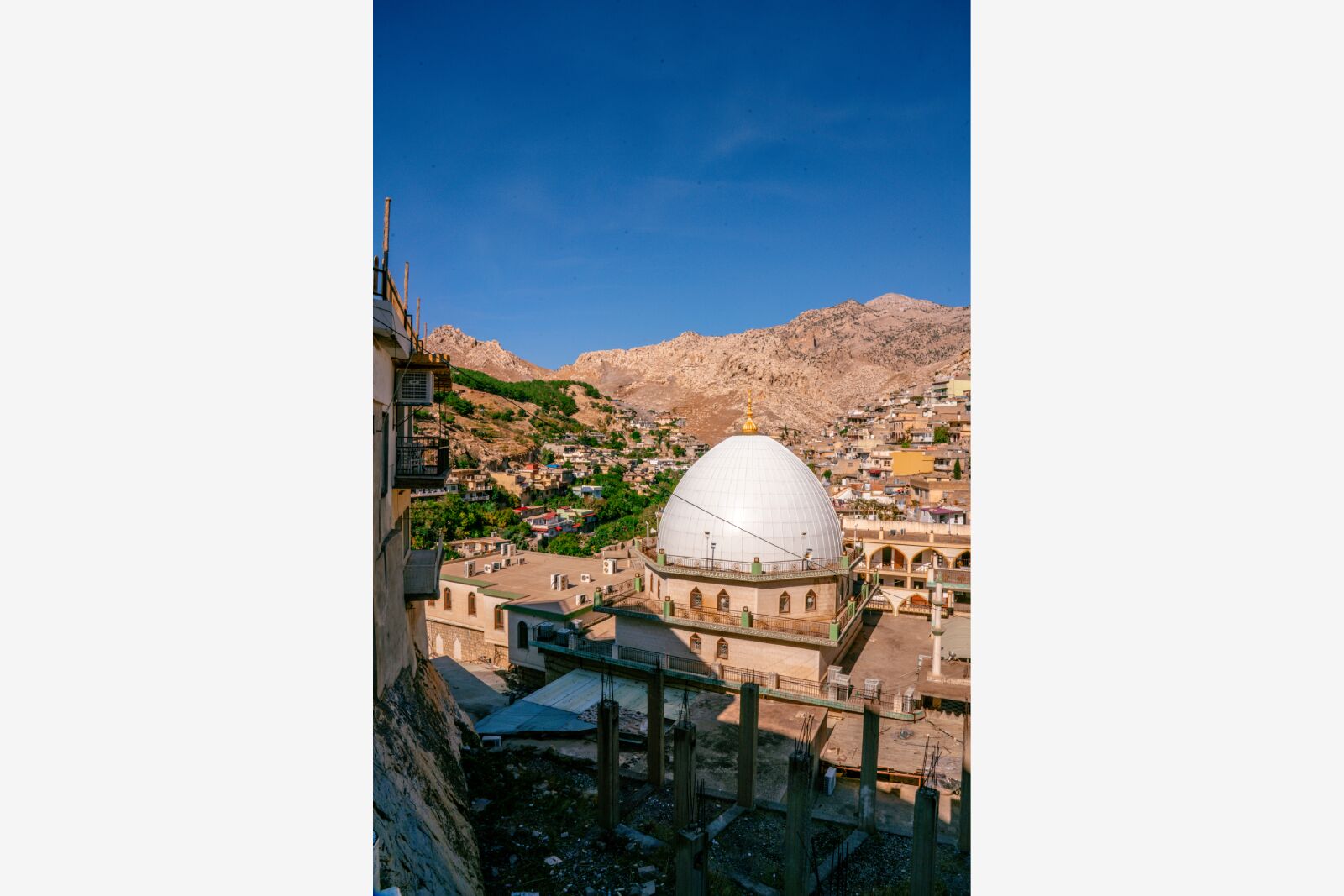

His trip took him to Baghdad, Al-Hillah (the site of the former city of Babylon), and Iraqi Kurdistan, an autonomous region within Iraq. Kurdish people live in Iraq, Iran, Türkiye, and Syria, though they have no official country. Fights for recognized independence continue in various regions, but in Iraq, the Kurdistan region has special status with a high level of autonomy, including its own parliament, president, and security forces.

The film starts on March 19, 2003, when then-President George W. Bush announced the start of the military invasion of Iraq during a televised White House address. The previous year, Bush had signed the Authorization for Use of Military Force Against Iraq Resolution of 2002, more commonly known as the “Iraq Resolution.” America’s on-the-ground presence lasted until December 2011, when the country’s final troops were removed. More than 4,400 American service members were killed, and between 300,000 and 500,000 Iraqis were killed or died from war-related incidents.

“When the war was going on in Iraq, I was a young teenager,” van Oorsouw says. “So understanding what went on at the time was very foreign to me. I had not really traveled. Even in the Netherlands I was fed the media and saw things happening but didn’t understand why.”

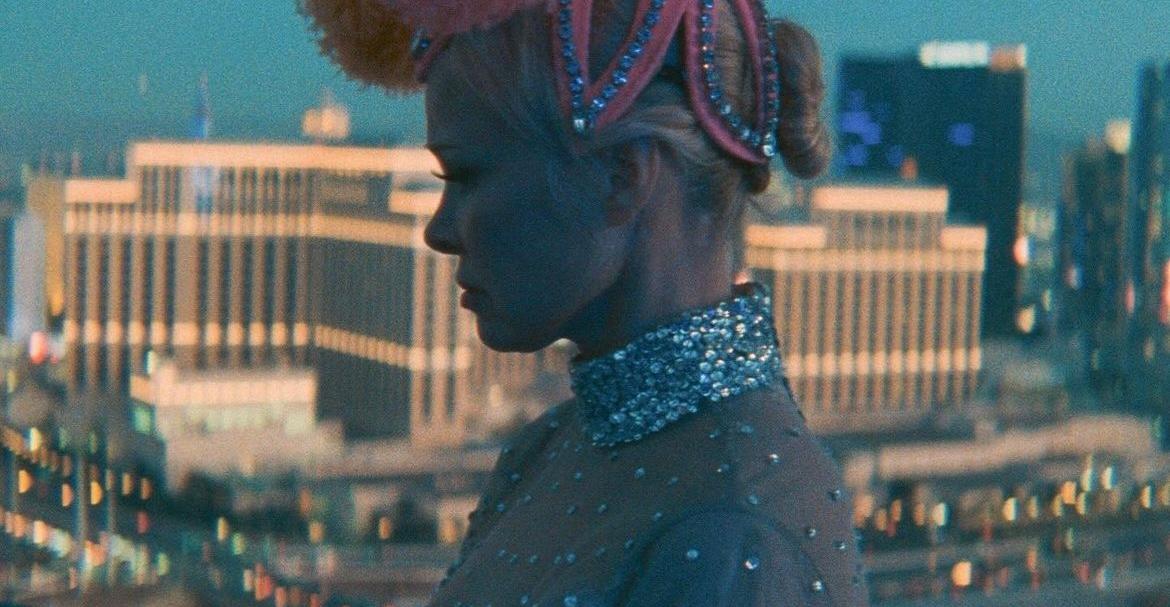

Photo: Reinier van Oorsouw

This isn’t van Oorsouw’s first film with Matador Network exploring a country generally considered off-limits for Western travelers. In 2018, van Oorsouw and Matador worked together on a similar project centered on Iran. It was a natural next step for Van Oorsouw, who got his start filming travel stories around the world with Lonely Planet. In 2008, he started Beyond Borders Media, which has grown into a communications agency for developmental work and human interest stories, frequently working with NGOs and the United Nations.

Van Oorsouw lives in Lima, Peru, with his wife and their two-year-old child. Daycare in Peru is much better than in van Oorsouw’s native Netherlands, he says, and Peru’s weather, food, and backyard are certainly welcome, too. “My interest in the world comes from traveling, understanding, and demystifying other cultures. What we’re taught in school is usually black and white — one thing or the other but nothing in between,” van Oorsouw says. “This travel opened my eyes to see a range of colors, and every time you dive into a new adventure, you come back with answers but way more questions as well.”

Majed Amer, translator who grew up in Baghdad and moved to the Netherlands during the war. Photo: Reinier van Oorsouw

He traveled with cameraman Jerry de Mars and friend and translator Majed Amer, who used to live in Baghdad but moved to the Netherlands during the war. Van Oorsouw’s film covers cities, towns, and historic sites, including Saddam Hussein’s graffiti-covered and cavernous abandoned palace, as well as the remains of the ancient city of Babylon. It’s more than sights and views. Local food, spices, teahouses, and coffeehouses were an important part of his experience and provided a chance to have deeper, spontaneous conversations with locals.

“Our perception of the world is very different than reality,” van Oorsouw says. “I would say I’m a nuance seeker in this case, and I’m mainly trying to amplify the local voices. I can pretend that I know a place if I go on a road trip for a week or two, but that’s only an impression — it’s one side. It’s still fed by media impressions that I have. It’s a conversation starter, and I’m hoping to show something else than [what] the traditional media show you: that there are people there trying to make the best out of their lives. Of course there are extremes in places, but there are in the United States as well.”

We caught up with van Oorouw to learn more about what it’s like to travel to Iraq as a Westerner right now, and what travelers need to know before going.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

What goes through your mind when deciding to visit a place typically considered “dangerous” and “not a tourist destination?”

There are places with a higher risk where [when] I go with my “gringo” face, it’s obvious that I stand out. For places like Iraq, Iran, Afghanistan nowadays, places like Venezuela for instance, you can go there, there’s no wars. But there is a type of danger. So if you go to a place like this, identify the danger. How can I reduce the risk? If I reduce it as much as possible, am I comfortable enough to go? But you can never eliminate risk. If you don’t want to take that risk, go on a cruise in the Caribbean. You’ll be fine. Or maybe the cruise sinks.

How do you make that calculation of whether somewhere is safe enough to visit?

The whole idea behind this series is to go in without any form of preparation other than a ticket, visa, and renting a car. My idea is if you can freely do a road trip, navigate as you go, find somewhere unplanned to stay in the evening, and manage that relatively comfortably, then I feel the country is not that bad. That’s the threshold. This was certainly the case for all that I’ve seen in the Kurdistan part of Iraq, but also in the Iraqi part of Iraq.

A local who sings for the camera in the film. Photo: Reinier van Oorsouw

Late at night driving around was perfectly safe. There’s a lot of checkpoints, and the people who work at these checkpoints will raise a few eyebrows of why where are three Westerners driving around and they think we’re a bit loco. But if you approach it with a smile, if there’s nothing you’ve done wrong, if you know that there are no restrictions and your paperwork is all okay, it’s rare to get into trouble.

Were there any instances that made you pause on this trip to Iraq?

While we were in Kurdistan, there were some security issues. On the way through this mountain pass to this town, we got a notification from the Dutch consulate in Kurdistan that there was a drone strike by either Turkish or Iranian forces in exactly that town where we were going. I thought, okay, it’s like rain that has already fallen. So the chance that we get hit by another drone strike is almost zero, it won’t come our way again. But is it good that an hour after there’s a drone strike, there are three white guys showing up; “hey guys, how are you doing?” So there’s the sensible thing of turning around and taking another route.

I also understand that for a lot of people, hearing the words “drone strike nearby me” is already a motive not to travel. But in there is a nuance.

What can the average traveler take away from that?

If you want a vacation, I would say don’t go to Kurdistan or the whole of Iraq. If you want an adventure, if you know your way around, if you’re a bit of a seasoned traveler, you can do it. Just understand what you’re going to. If you’re not all about beaches and sipping piña coladas at sunset, but have an exploring mindset and want to learn about a place through the eyes of local people, these are very interesting times and you can do so in a way that is relatively safe.

It’s travel with an interest in understanding what’s going on in the world. I wouldn’t even call it tourism, but cultural understanding.

Photo: Reinier van Oorsouw

Does seeing everyday life in Iraq and other places you’ve been change how you think about other places?

There’s almost always a rush to explain the exact opposite from what you’re used to. Understanding and trying to have empathy with other points of view will help, at least they help me, bring more understanding of life and different cultures.

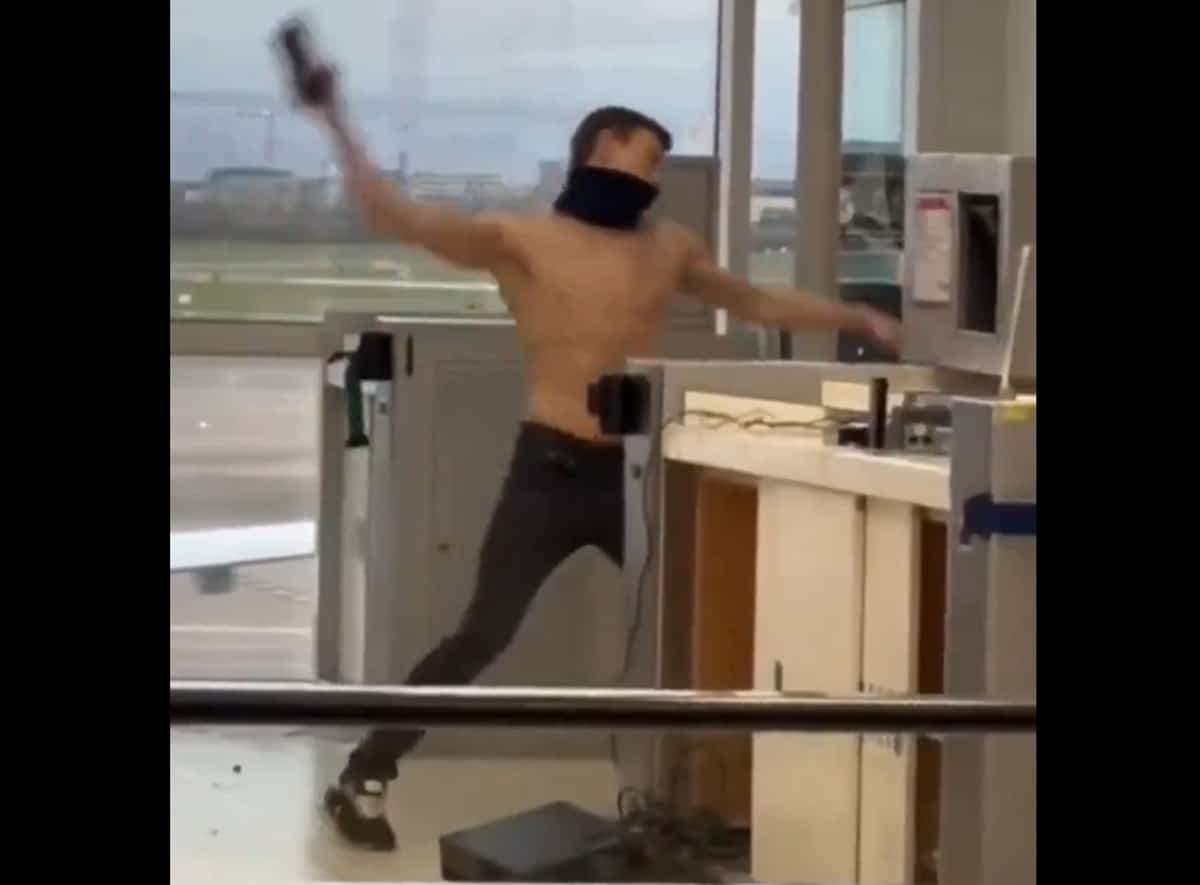

I’ve seen my fair share of guns in Iraq, because they’re out there as well. It’s just that people don’t wave them around and it’s only guards, police, or army who usually carry guns. I don’t want to hit the infamous topic of school shootings in the US, but I don’t think the words “school shooting” exists in Iraq.

If you come in as an outsider, everything seems foreign. But if you travel more and understand more of another place, you take that knowledge and you start to reflect it on the place where you’re from.

A big part of your experience involved meeting with locals, often by happenstance. What was that like?

People come up to you in the streets, especially if you walk around with a camera, and ask where you’re from. We had that on various occasions. Not everybody will talk to you in this manner, but people there with an open mind, they see travelers coming in as a chance to interact with people from other cultures.

It feels like a lot of the public perception about what’s dangerous revolves around politics.

The state of politics always affects a “dangerous” place because usually the source of danger comes through a political conflict — a ruler turning against their people, a rebel group trying to liberate a country (from their perspective). Usually politics or religion. Politics brings a difficult state for people, from pickpockets to kidnapping to fighting between factions. These are the symptoms you see.

Photo: Reinier van Oorsouw

Right, and the government is not necessarily of the people.

That’s exactly what I try to show. The context is always political or religious, but I want to see the people who, you know, think differently and have their own lives and what drives them. That is very much the thing that I want to highlight.

The region is one of the cradles of civilization and agriculture. How did that history play into the experience that you had? Going to the ancient parts of Babylon must have been something.

By chance, there was this group of local architects who were there. We started talking to them randomly and they were restoring parts of buildings with ancient methods. It really shows you how fragile a place like this is if it’s not well kept. This identity of Babylon is something for people from Iraq to be really proud of, you know. They had an empire here thousands of years ago. If this is safeguarded and preserved, this is a great thing they can look to as a united factor.

One of the places you went was Saddam Hussein’s palace that was never completed. What was that like?

This abandoned palace is on a hill that overlooks the ancient part of Babylon along the Euphrates River. Between the palm trees, the sun is shining. It’s a beautiful place. It also feels a bit arrogant to think like, “Hey, I’m the next ruler of Iraq. I have to plan my legacy here next to this ancient civilization.” Putting yourself out there doesn’t feel right to me as a humble Dutch person. But this place is, of course, loaded with history. You’re walking through the corridors that would have been his home, had it been finished in time.

Now, it’s this place where local people go and visit. The walls are full of graffiti. There’s no windows, no furniture. Just empty hallways in this megalomaniac building. To me, it symbolizes how quick and ego can be broken down. Everything in life is fragile. You will die eventually, I will die eventually. It’s the only guarantee we have in life. We are trying to make the most out of it in our lifetimes and I’m guessing he did the same.

In addition to the important sites, you mixed it up in local markets and restaurants. How did those food experiences play into the trip?

The taste of the Middle East has different herbs, spices, smells, tastes. The traditional food in every country is made by what’s from around there, and people in Iraq have had very different resources in different times.

Photo: Reinier van Oorsouw

You have teahouses, the ways coffee is made, how bread is made. The fresh produce they use, from the vegetables and the herbs to the spices. Diving into other food cultures is very enriching for me. The older I get, the more demanding my tongue and my stomach get. So I’m always trying to find new things that open my palate more.

I’m a coffee addict, so tasting different types of coffees is always a priority, and I try to take a few kilos home for personal use. Same goes for tea. I try to take some herbs, spices, dried fruits. Once you start to understand what other basic ingredients people are using, it’s nice to experiment a bit at home with it. I’m not at the chef’s standards of Iraqi cooking, but I’m just doing my best to make my own versions and share this with my friends because through these food experiences, you can let other people travel in a way to places that they won’t likely visit.

I’ve always thought of food as one of the best doors into culture.

People will always be interested in food. We all eat every day. This is one of the ways to really indulge yourself, because in Iraq and the Middle East in general, the spices and how a meal is approached on a daily basis is so different to me coming from a country like the Netherlands, where the menu traditionally has been relatively basic. There’s a lot to learn. The Dutch robbed all the spices and herbs from around the globe, and we’ve never tried to use them. I think the Dutch are the OGs of don’t get high on your own supply.

If you go to everything between Türkiye, Tajikistan, and out to Bangladesh, there’s a similarity. What is very much at the surface are the landscapes. If you cross the border from Iran to Iraq or Iran to Afghanistan, you see why there are borders: gradually the landscape changes, but within that the base ingredients are often the same, but used differently from country to country.

I’ve been in Pakistan, Tajikistan, the country of Georgia, and Türkiye, where they all have these types of dumplings, but in all different shapes and sizes, [changing] how they’re filled, how they’re served, what they’re eaten with.

Cameraman Jerry. Photo: Reinier van Oorsouw

Any last advice for the travelers (and armchair travelers) out there?

The world isn’t as bad as we think it is. We hold a lot of assumptions. I hope that people see that not all assumptions you have are correct. Try to look beyond the horizon and seek something that inspires you to go one step beyond.

It doesn’t have to be Iraq, of course. It can be in your own backyard. But try something different or new that you haven’t done before and that scares you a little. Go with an open mind to understand a new place. It’s an enriching experience. ![]()

![‘Karma’ – Netflix’s Korean Thriller Series Stars ‘Squid Game’ Actor Park Hae-Soo [Trailer]](https://bloody-disgusting.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/Karma_unit_104_B_A03554_cr-scaled.jpg)

![Underwater FPS ‘Chasmal Fear’ Surfaces on Steam April 17 [Trailer]](https://bloody-disgusting.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/chasmal.jpg)

![Inside the Vault [on SPIONE]](http://img.youtube.com/vi/gOltBk-9-rU/0.jpg)

![Please Watch Carefully [THE HEART OF THE WORLD]](http://www.jonathanrosenbaum.net/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/the-heart-of-the-world-5-300x166.jpg)

![Passenger Pops Open Champagne Mid-Flight—That Didn’t Go Over Quietly [Roundup]](https://viewfromthewing.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/passenger-pops-champagne.jpg?#)

.jpg?width=1920&height=1920&fit=bounds&quality=80&format=jpg&auto=webp#)

![[Podcast] Should Brands Get Political? The Risks & Rewards of Taking a Stand with Jeroen Reuven Bours](https://justcreative.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/jeroen-reuven-youtube-1.png)

![[Podcast] Should Brands Get Political? The Risks & Rewards of Taking a Stand with Jeroen Reuven](https://justcreative.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/jeroen-reuven-youtube.png)