Doors of Perception: Cinematic Sensations as Attractions

“Are You Experienced?” is the spring 2025 edition of the Notebook Insert, a seasonal supplement on moving-image culture.Illustration by Chau Luong.Why was cinema invented? Screenwriting manuals and certain film theorists have a ready answer: to tell stories in a dynamic modern form. This answer avoids the thorny thicket of film’s origins. As my friend and colleague André Gaudreault established, at the end of the nineteenth century the new technology of moving images did not have a single, dominant purpose; rather, it was employed in a diverse variety of what he calls “cultural series,” such as photographic exhibitions, journalistic reports, and magic shows.1 Theorist of technology Gilbert Simondon reminds us that technology continually reinvents and redefines its uses.2 Initially, moving photographic images supplied a precision tool that could record bodies in motion, allowing careful scientific analysis (the chronophotography of Étienne-Jules Marey, Eadweard Muybridge, and others). But moving images soon emerged from the physiological laboratory and were proclaimed as the latest innovation in photography, the logical next step after the snapshot, which froze action, often in ungainly postures. Now, photos could move… The early machinery of moving images became an attraction in itself: Edison’s Kinetoscope and Biograph’s Mutoscope were single-viewer peepshow devices installed in arcades, often coin-operated and showing risqué films. In addition to aiding scientific inquiry and providing sexual stimulation, early films made current events come alive: Newly elected presidents, diplomatic visits by world leaders, and sporting events appeared on the screen as a living newspaper. Film offered stage magician Georges Méliès a new way to create visual magic through in-camera techniques and by splicing the film strip, which would make objects and people magically appear, disappear, or transform. Advertisements for Dewar’s Whiskey or the latest brand of bicycle were projected onto billboards in New York City and other metropolises. Some of the earliest films also told stories: brief gags featuring young boys’ mischief with garden hoses (most famously, the Lumières’ L’Arroseur arrosé, 1895) or explosions caused by pouring kerosene in the kitchen stove, which blasted an astonished maid into heaven (as in George Albert Smith’s Mary Jane’s Mishap, 1903). Such stories—rather than developing characters or situations—are delivered more like a joke, with a sudden visual punch line.Decades later, historians stressed two aspects of the first films: their “realism,” and what theorist Christian Metz called a natural drive toward storytelling, which destined the new medium to become the twentieth century’s dominant vehicle for narrative.3 The realistic effect of seeing people and animals and vehicles in motion was celebrated by film’s first commentators as well: “This is life itself,” one critic responded to the Lumières’ first projections. But the desire to use cinema to tell stories as we usually understand them, creating characters living in a fictional world, came later. Rather than seeing cinema as inevitably taking the royal road to narrative, Gaudreault and I hold that the first movies were less interested in telling stories than in grabbing the viewer’s attention with what we call “attractions.”4 By 1906 or so, narrative dominated commercial filmmaking (although advertisements, educational films, porno, musical numbers, and crazy cartoons coexisted alongside fictional feature films as “added attractions,” they were relegated to the beginning of film programs and sometimes driven underground). Cinema never abandoned its primal mission of addressing its viewer through new technological means, folding attractions into storytelling to create the “movies” as we know them. As much as narrative, it was the sensual address of attractions that made the movies internationally popular, while cinema’s inherent visual fascination—its direct address to our senses—also created a radical cinematic avant-garde. Anna Held and a Mutoscope (American Mutoscope and Biograph Company, 1901).Touch, sight, hearing, smell, and taste—the traditional list of five senses. Scientists and mystics have sometimes proposed adding one or two more. Rather than telling stories or conveying information, a cinema that primarily addresses the senses as an attraction draws our attention to the way the senses work together—whether in harmony or discord. Scientists and philosophers have tackled such questions for as long as those disciplines have existed. But media artists and the devices and techniques they invent, employ, or simply imagine can make us experience the senses’ interactions directly. New media—film, video, television, home computers, 3D viewers—reveal our senses to be the object of manipulation and refinement.Jonathan Crary, in his groundbreaking work The Technics of the Observer: On Vision and Modernity in the Nineteenth Century, describes the sepa

“Are You Experienced?” is the spring 2025 edition of the Notebook Insert, a seasonal supplement on moving-image culture.

Illustration by Chau Luong.

Why was cinema invented? Screenwriting manuals and certain film theorists have a ready answer: to tell stories in a dynamic modern form. This answer avoids the thorny thicket of film’s origins. As my friend and colleague André Gaudreault established, at the end of the nineteenth century the new technology of moving images did not have a single, dominant purpose; rather, it was employed in a diverse variety of what he calls “cultural series,” such as photographic exhibitions, journalistic reports, and magic shows.1 Theorist of technology Gilbert Simondon reminds us that technology continually reinvents and redefines its uses.2 Initially, moving photographic images supplied a precision tool that could record bodies in motion, allowing careful scientific analysis (the chronophotography of Étienne-Jules Marey, Eadweard Muybridge, and others). But moving images soon emerged from the physiological laboratory and were proclaimed as the latest innovation in photography, the logical next step after the snapshot, which froze action, often in ungainly postures. Now, photos could move…

The early machinery of moving images became an attraction in itself: Edison’s Kinetoscope and Biograph’s Mutoscope were single-viewer peepshow devices installed in arcades, often coin-operated and showing risqué films. In addition to aiding scientific inquiry and providing sexual stimulation, early films made current events come alive: Newly elected presidents, diplomatic visits by world leaders, and sporting events appeared on the screen as a living newspaper. Film offered stage magician Georges Méliès a new way to create visual magic through in-camera techniques and by splicing the film strip, which would make objects and people magically appear, disappear, or transform. Advertisements for Dewar’s Whiskey or the latest brand of bicycle were projected onto billboards in New York City and other metropolises. Some of the earliest films also told stories: brief gags featuring young boys’ mischief with garden hoses (most famously, the Lumières’ L’Arroseur arrosé, 1895) or explosions caused by pouring kerosene in the kitchen stove, which blasted an astonished maid into heaven (as in George Albert Smith’s Mary Jane’s Mishap, 1903). Such stories—rather than developing characters or situations—are delivered more like a joke, with a sudden visual punch line.

Decades later, historians stressed two aspects of the first films: their “realism,” and what theorist Christian Metz called a natural drive toward storytelling, which destined the new medium to become the twentieth century’s dominant vehicle for narrative.3 The realistic effect of seeing people and animals and vehicles in motion was celebrated by film’s first commentators as well: “This is life itself,” one critic responded to the Lumières’ first projections. But the desire to use cinema to tell stories as we usually understand them, creating characters living in a fictional world, came later. Rather than seeing cinema as inevitably taking the royal road to narrative, Gaudreault and I hold that the first movies were less interested in telling stories than in grabbing the viewer’s attention with what we call “attractions.”4 By 1906 or so, narrative dominated commercial filmmaking (although advertisements, educational films, porno, musical numbers, and crazy cartoons coexisted alongside fictional feature films as “added attractions,” they were relegated to the beginning of film programs and sometimes driven underground). Cinema never abandoned its primal mission of addressing its viewer through new technological means, folding attractions into storytelling to create the “movies” as we know them. As much as narrative, it was the sensual address of attractions that made the movies internationally popular, while cinema’s inherent visual fascination—its direct address to our senses—also created a radical cinematic avant-garde.

Anna Held and a Mutoscope (American Mutoscope and Biograph Company, 1901).

Touch, sight, hearing, smell, and taste—the traditional list of five senses. Scientists and mystics have sometimes proposed adding one or two more. Rather than telling stories or conveying information, a cinema that primarily addresses the senses as an attraction draws our attention to the way the senses work together—whether in harmony or discord. Scientists and philosophers have tackled such questions for as long as those disciplines have existed. But media artists and the devices and techniques they invent, employ, or simply imagine can make us experience the senses’ interactions directly. New media—film, video, television, home computers, 3D viewers—reveal our senses to be the object of manipulation and refinement.

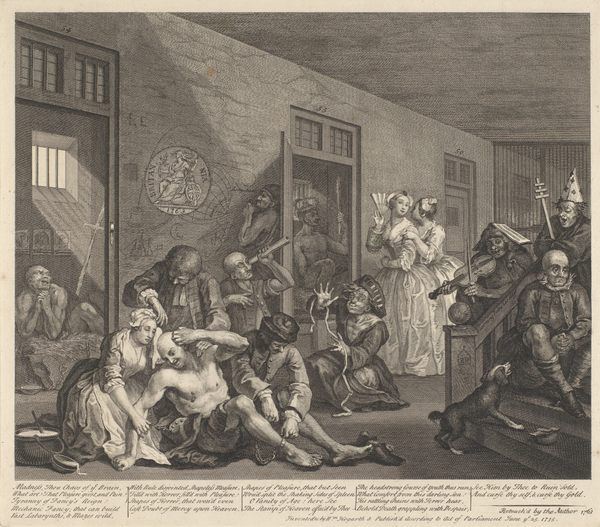

Jonathan Crary, in his groundbreaking work The Technics of the Observer: On Vision and Modernity in the Nineteenth Century, describes the separation of the senses (starting with the Enlightenment and René Descartes) as a pervasive modern understanding of how human beings grasp the world. Vision was conceived of in the Enlightenment as a form of touch, as the mind groped toward certainty by grasping reality through concepts. Crary claimed that a nineteenth-century invention, the stereoscope (the 3D viewer you can still buy in junk shops and antique malls), posed an alternative view of the relation between tactility and vision, one rooted deeply in the interaction of the body with a machine. In the modern era, a variety of machines have been designed that cheat or expand (take your pick) the human senses, creating new forms of experience and entertainment, a process which seems ever-expanding. Let’s stop viewing these attractions as a means to an end and learn to celebrate and appreciate the ride they take us on.

Beckers’ revolving stereoscopes (1873).

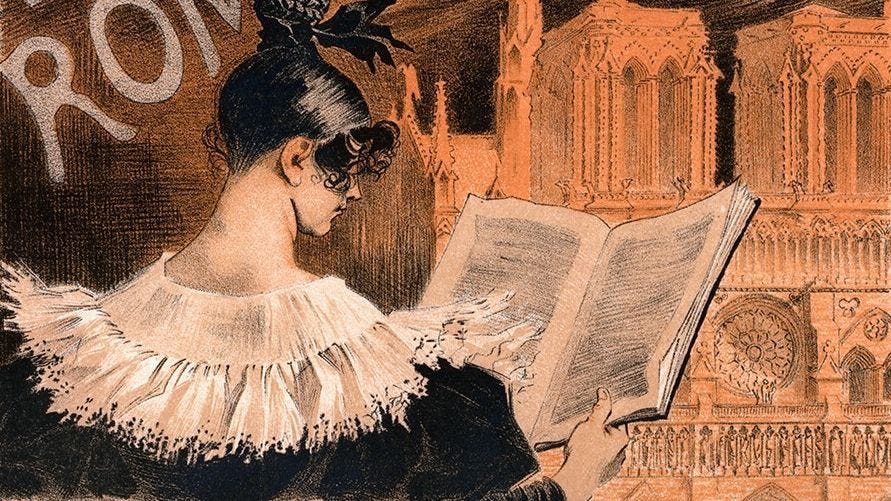

Separate in order to recombine. That might be the motto of artists and engineers who explore the attractions of sense perception. From Charles Baudelaire’s “Correspondences,” to Arthur Rimbaud’s vowel colors, to Wassily Kandinsky’s Yellow Sound, modern art was charged with a mission to divide and conquer the human sensorium. At the turn of the nineteenth century, the Symbolist theater in France strove to reimagine an art form that had traditionally been defined by speech and hearing (as the word auditorium, or the acoustic role of masks in Greek drama of projecting the voice, remind us). Experimental directors such as Lugné-Poe desired to return the senses to the theater, not only adding musical accompaniment to the action on stage, and carefully selected color to sets and costumes, but even on occasion passing out cotton swabs soaked in diverse scents for the audience to sniff at precise moments. The Gesamkunstwerk of Richard Wagner aimed at transforming the audience by orchestrating all the senses in a total environment. Wagner’s Bayreuth Festival Theatre was designed to bathe the auditorium in darkness and hide the orchestra while experimenting with new lighting technology on the stage, effectively enveloping the audience in a setting that seamlessly blended the senses.

In opposition to modern culture’s drive to control and instrumentalize human attention, reuniting the senses through artistic synesthesia took on both a mystic aura and rebellious purpose. As opposed to a growing sense of disembodiment resulting from modernity’s prioritization of vision over the other senses, this avant-garde celebration of the sensual demanded a return to the body and its inherence in the world. If hearing and sight remain dominant in our daily purposeful actions of work (and even, in many modern conditions, of play), the more intimate senses of touch, taste, and smell might better anchor us in our physical being.

Classical storytelling aims for coherent development. The principle of coherence seems to dominate commercial and even art cinema. But in the movies, narrative structure rarely makes up the whole show; the medium’s devices of attraction, spectacle, special effects, star glamour, and technical novelties grab audience attention. More than absorptive unity and coherence, the direct address of attractions works through addition and juxtaposition. The senses do not fuse together as much as rub against each other, creating montages of attractions rather than a seamless imaginary world. In a montage, a single sense supplements or evokes another.

Peter Kubelka conducting a master class at the Sonic Acts Festival in Amsterdam, 2002. (Photograph by Rosa Menkman.)

I recall my mentor, the great Austrian experimental filmmaker Peter Kubelka, describing his first experience of cinema as a child. An advertisement for a new sort of pudding was projected while the assembled audience gobbled samples; Kubelka’s earliest movie experience addressed his taste buds and eyes simultaneously. This sparked his understanding of film as more a means of feeding the senses than telling a story or representing the world. The class I took with Kubelka in the 1970s included not only close viewings of his own films, but savoring his cooking demonstrations (I can still taste the lamb testicles he fried in lemon juice).

Although this tendency has been mostly ignored by histories of film, there has long been an impulse to add the other senses to moving images. Silent cinema viewers watched moving images while they listened to music. The two forms certainly supplemented each other, but they were also experienced as coming from different spaces and having different sensual modes: live rather than recorded; present rather than projected. The theorist of the montage of attractions, Sergei Eisenstein, saw the coming of sound on film as adding another attraction, an aural counterpoint to the image. Beyond the ruling senses of sound and vision, other senses might provide added attractions.

Surrealist Salvador Dalí designed a device which would render films tactile and even obscene. Viewers were furnished with a sort of textured conveyor belt that would unroll while a film was projected on the screen. Materializing Aldous Huxley’s fictional “feelies,” this moving surface presented selected objects and textures to touch which would accompany the projected images, including a simulation of pubic hair for sex scenes.

Theatrical poster for Scent of Mystery (Jack Cardiff, 1960).

This sensual overload has remained an only occasional practice and recurrent fantasy of modernity; why has it never become as commercial as recorded sound? Besides a host of ideological and phenomenological reasons that privilege sight and hearing over the more intimate senses, the ambiguous and the ephemeral nature of touch, smell, and taste are hard to mass produce in a predictable manner. The fortune of Mike Todd and Hans Laub’s Smell-O-Vision is generally cited as a cautionary tale against overloading the sensual address of the movies. The tagline for this system claimed a historical progression: “First they moved (1895)! Then they talked (1927)! Now they smell (1959)!” It seems inevitable that this last phrase would have supplied critics with a readymade put-down of the new medium. Ultimately, only theaters in Los Angeles, New York City, and Chicago installed the system. A few years ago, the historic Selwyn Theatre in Chicago that had originally installed Smell-O-Vision was gutted, and a friend suggested we undertake an archeological excavation searching for relics of the system, which it turned out had been removed long before.

The only film made for Smell-O-Vision, Scent of Mystery (1960), can now be seen under the title Holiday in Spain on YouTube, bereft, of course, of fragrances and therefore both narrative coherence (since the odors directed the audience to clues in the course of the film’s mystery) and sensual attraction. But scent plays a key role in many classical films, such as the whiff of night-blooming jasmine that cues Humphrey Bogart to the real murderer in Dead Reckoning (1947) or the exotic mimosa perfume and sudden chill that announces the presence of the benevolent ghost in The Uninvited (1944), cued as well by an atonal passage in the score. The senses can be marshaled to provide narrative cues, even as they also function as attractions, as an imagined smell evokes hidden sins or supernatural influences.

L5: First City in Space (Toni Myers and Allan Kroeker, 1996).

Whatever great divides (aesthetic and ideological) separate the commercial and the avant-garde cinema, a fascination with exploring new technology and the senses joins them, and attractions could provide a shared sensibility. The role of 3D provides a complex and contested but shared regime. The scorn that many traditional critics dumped on 3D (recall Roger Ebert’s essay “Why I hate 3-D, and You Should Too”) was based mainly on the additional dimension being unnecessary to narrative development. I vividly recall seeing the 1996 IMAX 3D film L5: First City in Space on the recommendation of avant-garde master Ken Jacobs and realizing I had no interest in following its clichéd plot … but the feather fluttering on the costume of one of the characters provided sensual enjoyment worth the price of admission. 3D doesn’t simply place us “realistically” within the movie; our perception of tactility and vision merge due to a technology we cannot forget, as our senses are molded and our bodies respond.

At the end of the nineteenth century, the moving image immediately called into question the traditional boundary that defined the image: the frame. People and vehicles moved to the edge of the screen, then where did they go? Although the first New York City projections of the Vitascope placed an ornate golden frame around the screen, the films projected breached this limit. The trains that seemed to rush off the screen caused near panic in some viewers and introduced the direct address of attractions to the world. The movie screen itself, seemingly the most passive element of the cinema apparatus, has been subject to constant transformation since the beginning, stretched wider, variously curved, given the illusion of depth with stereoscopic images emerging from it, and now become so mobile it can be carried in our hands, connected to multiple networks of transmission. A conservative critical establishment may strive to put this genie back in the bottle by insisting that storytelling is the main objective of the movies, but the push and pull between narrative and attraction continues to draw viewers. Hopefully, it causes some of us to wonder how wide new technology might blow open the doors of perception.

- André Gaudreault, Cinéma et attraction (Paris: CNRS Editions, 2008), 111–144. ↩

- Gilbert Simondon, On the Mode of Existence of Technical Objects, trans. Cecile Malaspina and John Rogove (Univocal Publishing, 2017). ↩

- Christian Metz, Film Language: A Semiotics of the Cinema, trans. Michael Taylor (University of Chicago Press, 1990). ↩

- “Le cinéma des premiers temps, un défi á l'histoire du cinéma?” (co-authored André Gaudreault and Tom Gunning) in Histoire du Cinema: Nouvelles Approches, ed. J. Aumont, A. Gaudreault, and M. Marie (Publications de la Sorbonne, Paris, 1989). ↩

![‘Stygian: Outer Gods’ Comes to Early Access on April 14 [Trailer]](https://bloody-disgusting.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/stygian.jpg)

![‘Eyes Never Wake’ Puts Your Webcam to Terrifying Use [Trailer]](https://bloody-disgusting.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/eyesneverwake.jpg)

![Official Announcement Trailer for ‘Baptiste’ Delves Into the Gameplay and Psychological Terror [Watch]](https://bloody-disgusting.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/baptiste.jpg)

![‘The Toxic Avenger’ Made an Appearance on the Green Chicago River for St. Patrick’s Day! [Video]](https://bloody-disgusting.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/Screenshot-2025-03-16-100033.png)

![Form Counts [MIX-UP, ANATOMY OF A RELATIONSHIP, & GAP-TOOTHED WOMEN]](https://jonathanrosenbaum.net/wp-content/uploads/2009/09/mix-up.jpg)

.jpg?width=1920&height=1920&fit=bounds&quality=80&format=jpg&auto=webp#)

![[Podcast] Should Brands Get Political? The Risks & Rewards of Taking a Stand with Jeroen Reuven](https://justcreative.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/jeroen-reuven-youtube.png)