Metro 2033 Makes Killing Easy And Atrocity Quiet

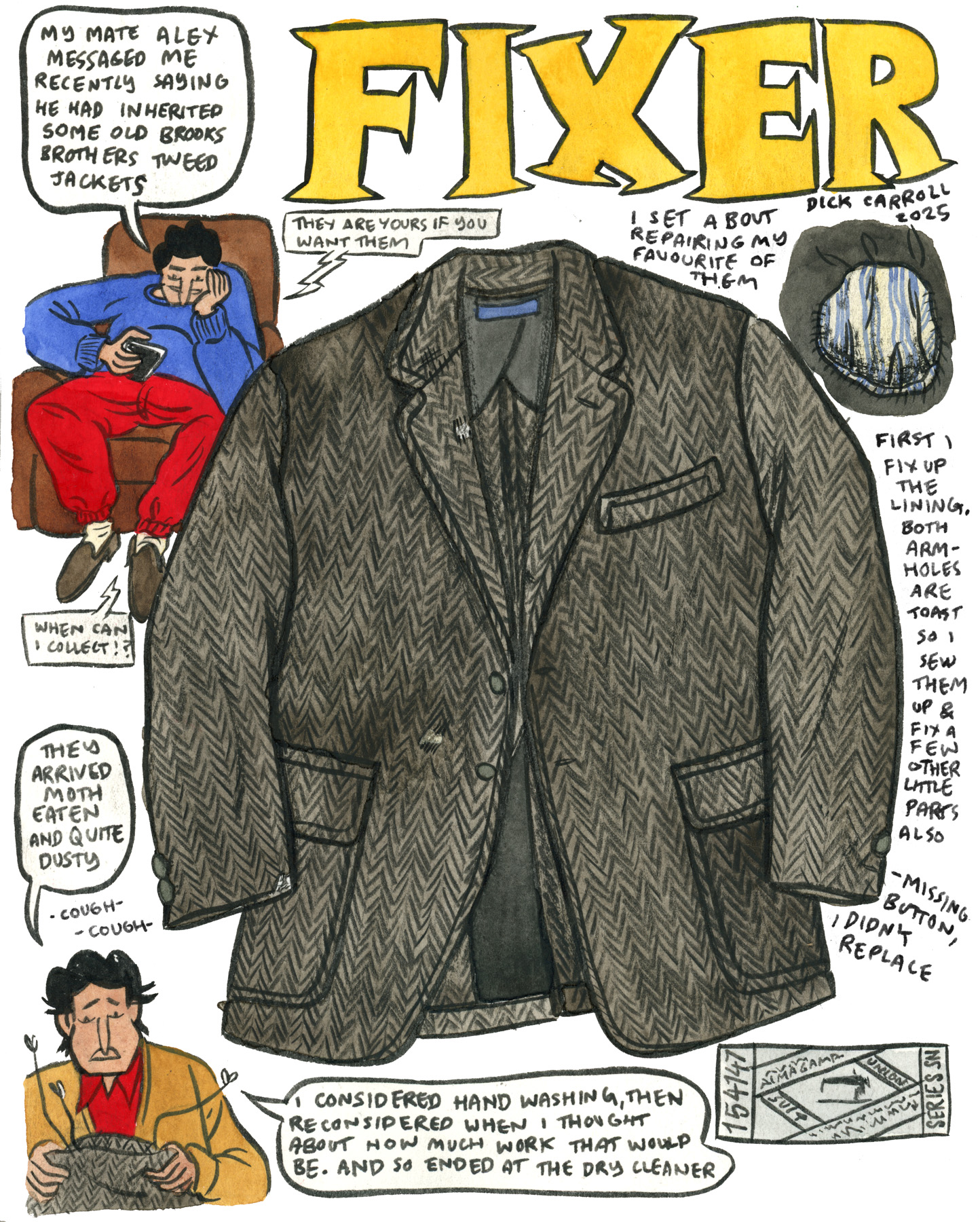

Metro 2033 is celebrating its 15-year anniversary today, March 16, 2025. Below, we examine how its subtle morality system helped to illustrate its broader points about humanity and violence.In video games, evil tends to be gigantic. Think of the rivers of blood in Baldur's Gate 3's evil endings or an army of Sith bowing to the player in Knights of the Old Republic. These moments are not exactly comical, but they have a glee to them. They have the joy of a cackling cartoon villain. In some sense, Metro 2033 is no exception. In the wake of atomic devastation, the Moscow metro populates itself with cruel bandits, monstrous mutants, and authoritarian militants. It is grimmer than the prior examples to be sure, but there is still a note of the absurd in its endless cruel men. But the game's ultimate quest, to destroy a mutant army of "Dark Ones" with an atomic weapon, casts the shadow of real-world brutality. Metro 2033 concerns itself with the miniscule decisions and delusions that build up to atrocity, all under an atomic shadow. Unlike most other morality systems, Metro 2033 does not announce itself; instead it builds up the protagonist's character through tiny individual moments: beats of butterfly wings that become a hurricane.This works in a simple binary way. Completing certain tasks will net protagonist Artyom moral points. Get enough points and he'll have the opportunity for the good ending. In contrast to other games with morality systems, the player cannot see how many points Artyom has earned. There is only a sound and a flash of light (a more ominous sound plays when Artyom loses moral points). Fittingly, Artyom has humble origins. He is not a soldier. His station is distant from the comparatively sprawling central stations of the Metro and he has rarely left his home. He is as explicit a player-insert as a game like this can muster. More familiar with the world than the player to be sure, but also an outsider and newcomer to most of it. A sort of greatness awaits him. The game opens in media res: Artyom outfitted with military-grade gear and fighting a massive migration of mutants on the surface. But at the start, he is only arrogant because of his youth, not his power. He is incapable of atrocity; it takes an invitation for him to become a monster.Continue Reading at GameSpot

Metro 2033 is celebrating its 15-year anniversary today, March 16, 2025. Below, we examine how its subtle morality system helped to illustrate its broader points about humanity and violence.

In video games, evil tends to be gigantic. Think of the rivers of blood in Baldur's Gate 3's evil endings or an army of Sith bowing to the player in Knights of the Old Republic. These moments are not exactly comical, but they have a glee to them. They have the joy of a cackling cartoon villain. In some sense, Metro 2033 is no exception. In the wake of atomic devastation, the Moscow metro populates itself with cruel bandits, monstrous mutants, and authoritarian militants. It is grimmer than the prior examples to be sure, but there is still a note of the absurd in its endless cruel men. But the game's ultimate quest, to destroy a mutant army of "Dark Ones" with an atomic weapon, casts the shadow of real-world brutality. Metro 2033 concerns itself with the miniscule decisions and delusions that build up to atrocity, all under an atomic shadow. Unlike most other morality systems, Metro 2033 does not announce itself; instead it builds up the protagonist's character through tiny individual moments: beats of butterfly wings that become a hurricane.

This works in a simple binary way. Completing certain tasks will net protagonist Artyom moral points. Get enough points and he'll have the opportunity for the good ending. In contrast to other games with morality systems, the player cannot see how many points Artyom has earned. There is only a sound and a flash of light (a more ominous sound plays when Artyom loses moral points). Fittingly, Artyom has humble origins. He is not a soldier. His station is distant from the comparatively sprawling central stations of the Metro and he has rarely left his home. He is as explicit a player-insert as a game like this can muster. More familiar with the world than the player to be sure, but also an outsider and newcomer to most of it. A sort of greatness awaits him. The game opens in media res: Artyom outfitted with military-grade gear and fighting a massive migration of mutants on the surface. But at the start, he is only arrogant because of his youth, not his power. He is incapable of atrocity; it takes an invitation for him to become a monster.Continue Reading at GameSpot

![‘Eyes Never Wake’ Puts Your Webcam to Terrifying Use [Trailer]](https://bloody-disgusting.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/eyesneverwake.jpg)

![Official Announcement Trailer for ‘Baptiste’ Delves Into the Gameplay and Psychological Terror [Watch]](https://bloody-disgusting.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/baptiste.jpg)

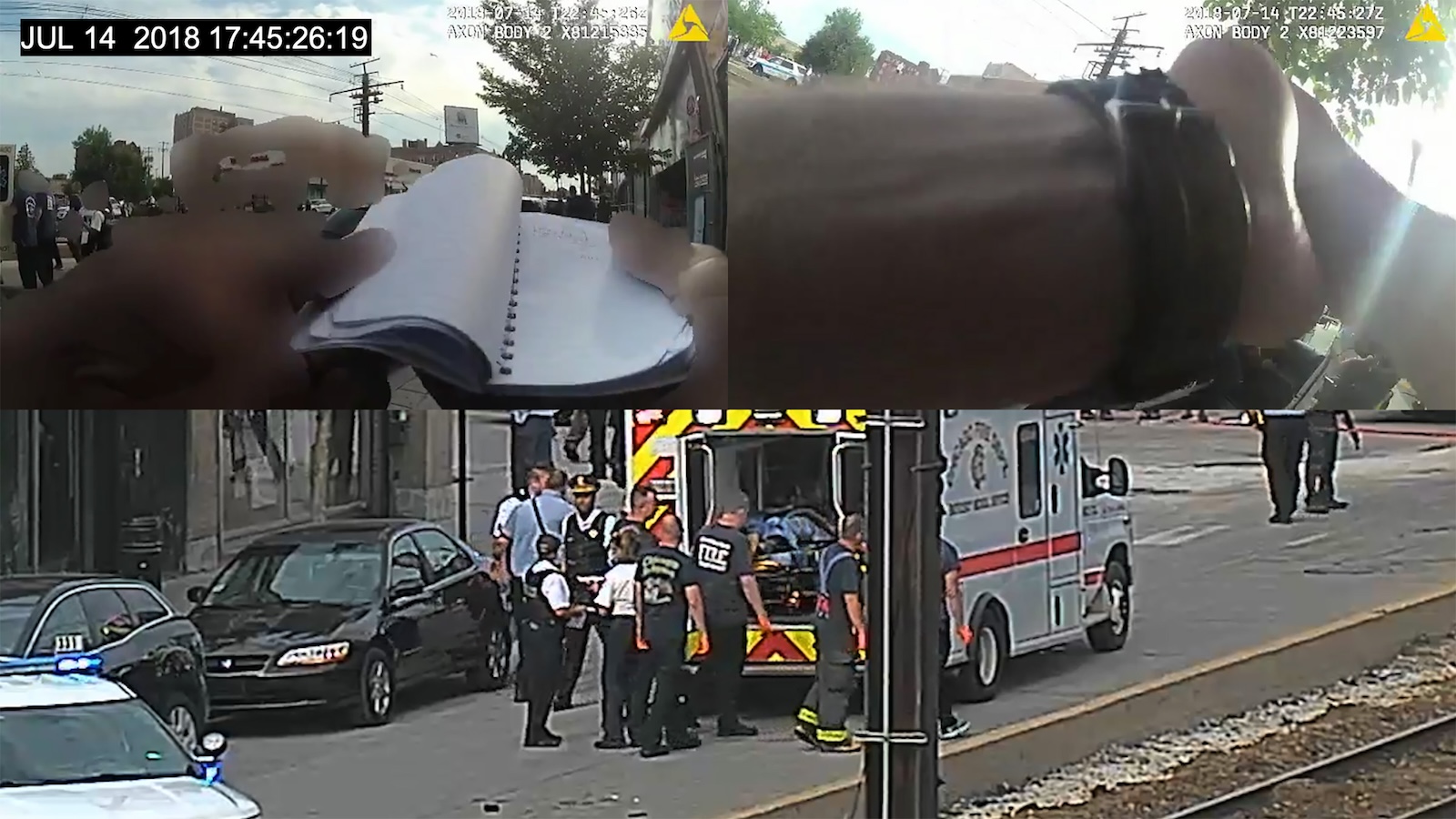

![‘The Toxic Avenger’ Made an Appearance on the Green Chicago River for St. Patrick’s Day! [Video]](https://bloody-disgusting.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/Screenshot-2025-03-16-100033.png)

![Form Counts [MIX-UP, ANATOMY OF A RELATIONSHIP, & GAP-TOOTHED WOMEN]](https://jonathanrosenbaum.net/wp-content/uploads/2009/09/mix-up.jpg)

.jpg?width=1920&height=1920&fit=bounds&quality=80&format=jpg&auto=webp#)

![[Podcast] Should Brands Get Political? The Risks & Rewards of Taking a Stand with Jeroen Reuven](https://justcreative.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/jeroen-reuven-youtube.png)