Hieronymus Bosch with Lens Flares: Paul W. S. Anderson on “In the Lost Lands”

In the Lost Lands (Paul W. S. Anderson, 2025).Paul W. S. Anderson is beaming a boyish grin when I log into our video call. Salt-and-pepper hair aside, you wouldn’t guess that the B-movie maven was turning sixty on the day of our chat. “I’m actually getting to spend my first birthday in three years with Milla,” he says by way of preamble while I fumble with my recording device. Anderson is cinema’s preeminent wife guy, and the Milla in question is Milla Jovovich, mother to his three daughters and star of seven collaborations.Theirs is one of the great actor-director partnerships of the 21st century—she the high-kicking badass with charisma to burn, he the no-nonsense conductor of bodies in (slow) motion; the enthusiastic facilitator of his leading lady’s uncomplicated cool.The surly critical dismissal of their new film, In the Lost Lands (2025), tells a familiar story. Content to miss the wood for the trees, Anderson’s detractors have been complaining about one-dimensional characters, inane dialogue, and the frenetic cacophony of his style since his ram-raiding debut, Shopping (1994). But as any member of his growing army of disciples will tell you, Anderson’s spatially coherent staging and resplendent image-making is a balm in the contemporary landscape of genre filmmaking. Where his critics sneer at an aesthetic that, to their eyes, resembles a video game cutscene, his defenders see a filmmaker working at the vanguard of the digital revolution.The cutscene dig would likely be water off a duck’s back to a filmmaker for whom video-game adaptations are nothing short of vocational. Anderson scored a major hit when he brought the arcade beat-em-up Mortal Kombat to the big screen in 1995, while his six-film Resident Evil franchise—based on the hugely successful series of Capcom games—took in more than a billion dollars at the international box office. The pandemic put paid to any franchise ambitions for his previous film, the visually striking Monster Hunter (2020)—another Capcom adaptation—which failed to recoup its $60 million budget. But Anderson has been making enterprising pulp fiction for more than half his adult life, and knows full well that some pictures—like his 1997 sci-fi hellraiser Event Horizon, which took a critical drubbing on release—need time to find their audience.Superficially, In the Lost Lands is a departure from recent projects. Like The Three Musketeers (2011), it’s a literary adaptation (from a wisp of a George R. R. Martin short story) and one of the few films on which Anderson hasn’t taken a writing credit. There’s a greater emphasis on character dynamics, between the two leads at least—perhaps testament to Jovovich’s first credit as producer on one of her husband’s films—and an unusually relaxed vibe to the ride between action sequences.Otherwise it’s business as usual: some complex lore masking a straightforward quest narrative through a spectacularly elaborate world—a steampunk, quasi-medieval fantasy realm of witches, werewolves, and religious fanatics that serves as an expressionistic backdrop for Anderson to hang his signature set pieces and jaw-dropping master shots. Borrowing and discarding western iconography at will, while channeling Albert Pyun to draw on anything from Mad Max: Fury Road (2015) to Heavy Metal (1981), In the Lost Lands wears its patchwork of influences on its sleeve. Yet there’s no mistaking it for anything but a PWSA joint. Utilising a gaming engine to embellish built locations, Anderson’s visual sensibilities scale new operatic heights. In lending his peerless eye for composition, space, and movement to a production method that conjugates his love for video games and practical filmmaking, Anderson has come away with his most beautiful film to date.In the Lost Lands (Paul W. S. Anderson, 2025).NOTEBOOK: Happy birthday! Today is a big one, right?PAUL W. S. ANDERSON: That’s right! I’m celebrating it with George R. R. Martin. We’re having a premiere in Santa Fe because this is where George lives. He’s all in on Santa Fe. He loves it, and has lived here for like 40 years. He owns a cinema here called the Jean Cocteau, which he saved. It was the local cinema that closed down, so he poured a ton of money into it and turned it into this big event space. So we thought we’d have the premiere of In the Lost Lands in Santa Fe, in his own theater. And then the afterparty is in his speakeasy, which is called The Milk of the Poppy. So I’m looking forward to that.NOTEBOOK: You had a big anniversary last year too, with your first film, Shopping, turning 30. When was the last time you watched that one?ANDERSON: Oh, a long time ago. I see bits and pieces of it occasionally. And I see the opening helicopter shots all over the place. I spent years trying to get that film off the ground. It was a patchwork of international financing. I got paid next to nothing to write and direct it, and to help produce it. I looked at the movie and thought, It needs a stronger opening. But we h

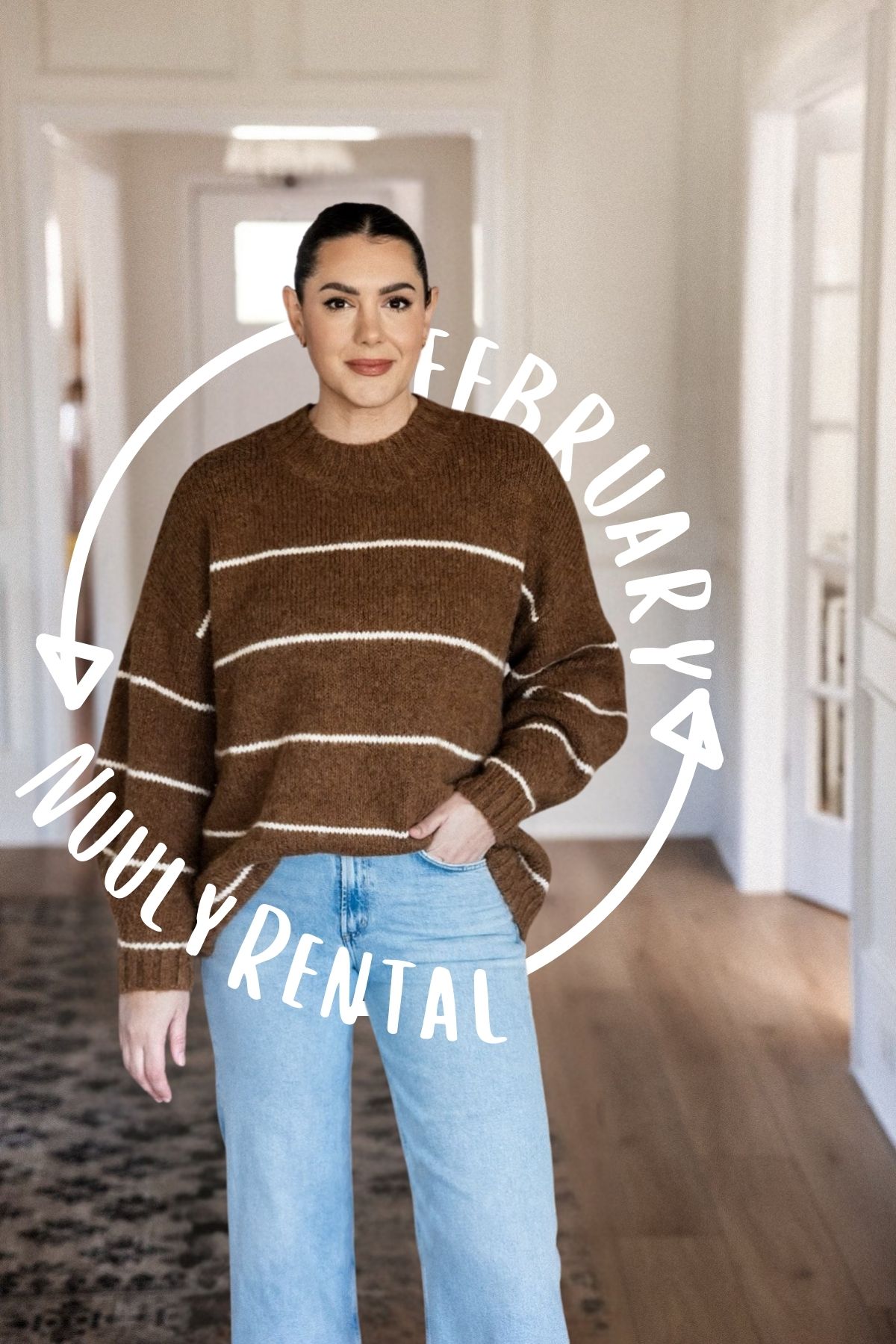

In the Lost Lands (Paul W. S. Anderson, 2025).

Paul W. S. Anderson is beaming a boyish grin when I log into our video call. Salt-and-pepper hair aside, you wouldn’t guess that the B-movie maven was turning sixty on the day of our chat. “I’m actually getting to spend my first birthday in three years with Milla,” he says by way of preamble while I fumble with my recording device. Anderson is cinema’s preeminent wife guy, and the Milla in question is Milla Jovovich, mother to his three daughters and star of seven collaborations.

Theirs is one of the great actor-director partnerships of the 21st century—she the high-kicking badass with charisma to burn, he the no-nonsense conductor of bodies in (slow) motion; the enthusiastic facilitator of his leading lady’s uncomplicated cool.

The surly critical dismissal of their new film, In the Lost Lands (2025), tells a familiar story. Content to miss the wood for the trees, Anderson’s detractors have been complaining about one-dimensional characters, inane dialogue, and the frenetic cacophony of his style since his ram-raiding debut, Shopping (1994). But as any member of his growing army of disciples will tell you, Anderson’s spatially coherent staging and resplendent image-making is a balm in the contemporary landscape of genre filmmaking. Where his critics sneer at an aesthetic that, to their eyes, resembles a video game cutscene, his defenders see a filmmaker working at the vanguard of the digital revolution.

The cutscene dig would likely be water off a duck’s back to a filmmaker for whom video-game adaptations are nothing short of vocational. Anderson scored a major hit when he brought the arcade beat-em-up Mortal Kombat to the big screen in 1995, while his six-film Resident Evil franchise—based on the hugely successful series of Capcom games—took in more than a billion dollars at the international box office.

The pandemic put paid to any franchise ambitions for his previous film, the visually striking Monster Hunter (2020)—another Capcom adaptation—which failed to recoup its $60 million budget. But Anderson has been making enterprising pulp fiction for more than half his adult life, and knows full well that some pictures—like his 1997 sci-fi hellraiser Event Horizon, which took a critical drubbing on release—need time to find their audience.

Superficially, In the Lost Lands is a departure from recent projects. Like The Three Musketeers (2011), it’s a literary adaptation (from a wisp of a George R. R. Martin short story) and one of the few films on which Anderson hasn’t taken a writing credit. There’s a greater emphasis on character dynamics, between the two leads at least—perhaps testament to Jovovich’s first credit as producer on one of her husband’s films—and an unusually relaxed vibe to the ride between action sequences.

Otherwise it’s business as usual: some complex lore masking a straightforward quest narrative through a spectacularly elaborate world—a steampunk, quasi-medieval fantasy realm of witches, werewolves, and religious fanatics that serves as an expressionistic backdrop for Anderson to hang his signature set pieces and jaw-dropping master shots. Borrowing and discarding western iconography at will, while channeling Albert Pyun to draw on anything from Mad Max: Fury Road (2015) to Heavy Metal (1981), In the Lost Lands wears its patchwork of influences on its sleeve.

Yet there’s no mistaking it for anything but a PWSA joint. Utilising a gaming engine to embellish built locations, Anderson’s visual sensibilities scale new operatic heights. In lending his peerless eye for composition, space, and movement to a production method that conjugates his love for video games and practical filmmaking, Anderson has come away with his most beautiful film to date.

In the Lost Lands (Paul W. S. Anderson, 2025).

NOTEBOOK: Happy birthday! Today is a big one, right?

PAUL W. S. ANDERSON: That’s right! I’m celebrating it with George R. R. Martin. We’re having a premiere in Santa Fe because this is where George lives. He’s all in on Santa Fe. He loves it, and has lived here for like 40 years. He owns a cinema here called the Jean Cocteau, which he saved. It was the local cinema that closed down, so he poured a ton of money into it and turned it into this big event space. So we thought we’d have the premiere of In the Lost Lands in Santa Fe, in his own theater. And then the afterparty is in his speakeasy, which is called The Milk of the Poppy. So I’m looking forward to that.

NOTEBOOK: You had a big anniversary last year too, with your first film, Shopping, turning 30. When was the last time you watched that one?

ANDERSON: Oh, a long time ago. I see bits and pieces of it occasionally. And I see the opening helicopter shots all over the place. I spent years trying to get that film off the ground. It was a patchwork of international financing. I got paid next to nothing to write and direct it, and to help produce it. I looked at the movie and thought, It needs a stronger opening. But we had no money left. So the meager director’s fee that I had made over the past three years, I put back into the film to get those helicopter shots. And they really made the movie. They opened up the scope of the film and really felt like a statement of intent, that this was something very cinematic. Then, over the years, I’ve seen clips from those helicopter shots turning up in other people’s movies. One of the opening shots of Moon [2009], for example, is the opening shot of Shopping. I deferred my director’s fee to pay for them, and despite the fact that someone somewhere is selling it as stock footage, I’m still waiting to get my deferment check back.

NOTEBOOK: Are there any plans to restore the film?

ANDERSON: Funnily enough, yesterday I got approached by someone who wanted to do a novelization of it. I thought, Really? They said, “We think there’s an audience for it.” So maybe the Shopping bandwagon is starting to roll again.

NOTEBOOK: I’d forgotten about Sadie Frost’s character playing the handheld racing game until I revisited it recently.

ANDERSON: Video games! They were in there.

Shopping (Paul W. S. Anderson, 1994).

NOTEBOOK: Do you think video-game adaptations are still the final frontier for genre respectability these days?

ANDERSON: Hollywood has had more success than ever with video-game adaptations, so it isn’t looked down upon as much as it used to be. I remember when I was adapting Mortal Kombat, my first Hollywood movie, people went, “How can you even base a movie on a video game? And why would you want to?” They spoke like you ought to be wearing rubber gloves while you were doing it. It was very distasteful. I don’t think they’re viewed that way now. As a piece of commerce, Hollywood has accepted them. They’re a little more respectable, and I think that’s a good thing.

I’m actually developing another video-game adaptation at the moment. But for me, it’s got nothing to do with respectability or commerciality. I just grew up playing video games, and I really love them. I’m interested in the narrative form they present, which is slightly different to the cinematic form of storytelling. But I think increasingly, to an audience that grew up playing video games, that kind of elliptical version of storytelling is something that has become more acceptable. The language of video games has been absorbed into cinema, and vice versa, of course.

NOTEBOOK: You’ve been flirting with the western for some time now, as a director on Soldier [1998] and as writer-producer on Resident Evil: Extinction [2007], but In the Lost Lands really leans into the genre signifiers.

ANDERSON: Yeah, absolutely. More than any film I’ve done. Is it a fully fledged western? No, but it’s getting there. It’s got a lot of the imagery, and a lot of the storytelling tropes that you would expect, especially from a spaghetti western. Two characters embark across a difficult landscape on a mission, not quite trusting each other, but learning respect for one another as they go. That could be The Good, The Bad and the Ugly [1966] or For a Few Dollars More [1965]. Or with the female-male component, Two Mules for Sister Sara [1970]. That was something that was organic to George’s original writing, and one of the reasons that I thought it would make a great movie.

Soldier (Paul W. S. Anderson, 1998).

NOTEBOOK: There’s also a video-game logic to it as well, in the way that it moves episodically between distinct locations for a series of set pieces.

ANDERSON: A lot of great westerns are, at heart, road movies. And with a great road movie, you may be with the same bunch of people, but you’re going to different places and you want to feel that progression. One of the exciting things about In the Lost Lands was that because of the way we mounted the movie, I got to build all of those locations. I got to build them from scratch. We weren’t stuck with, Okay, you’re in Cape Town, and these are the five postapocalyptic-looking locations. Pick three of them, and that’s the basis of your movie. We started working on the environments nine months before we shot the movie. And then we continued working on them for nearly a year and a half after we finished principal photography.

It was great that you could plan it, too. You weren’t just beholden to available locations and shooting times. If you were to watch In the Lost Lands on fast-forward, you’d see that the whole movie changes color. It starts in a very specific color tone, but then it really moves, so that by the end of the film, hopefully the audience feels that they’ve taken a real journey.

NOTEBOOK: This sense of set-piece staging posts is underlined by the map you use to segue between spaces. It’s a recurring motif throughout your filmography, from the wireframe mazes in the Resident Evil films to the wargaming map in The Three Musketeers. Tell me a bit about their function and the importance of spatial orientation for the viewer.

ANDERSON: I’ve always liked knowing my geography in movies, like the different landscapes that people are traveling between in Lost Lands. That’s a reference back to the books I grew up reading. You open The Lord of the Rings or a Conan book, and the first thing you see is the map: Here’s Hyperborea, here’s Middle Earth, here’s the world of the book. I love that, and I think audiences love that, because you can dive into it. Sometimes there are bits of the map that you don’t go to, so your imagination takes care of what those bits are like. We were creating the world of the Lost Lands from scratch, so I thought that a map was very appropriate.

When I started working, it was around the time that shaky-cam was really taking off, especially in Hollywood movies. A lot of directors were like, Arghh! Geographic logic, be damned! We’re just gonna go rarghhhh! That can give your action scenes and your movie a lot of kinetic energy for a while, but I think it ends up being disorienting for an audience, and ultimately reduces the impact of the action if you don’t know what’s happening to who. So I’ve always strived to combine kinetic energy with logic and geography. For me, that’s the holy grail in action cinematography: for the audience to know what’s going on, and be thrilled by it. You don’t have to sacrifice geography for energy.

Resident Evil: Afterlife (Paul W. S. Anderson, 2010).

NOTEBOOK: Speaking of kinetic energy, you’re back working with Niven Howie as editor, who cut Resident Evil: Afterlife [2010] and Resident Evil: Retribution [2012], after a two-film break. How would you describe his influence on your work versus that of Doobie White, who cut Monster Hunter and Resident Evil: The Final Chapter [2016] for you?

ANDERSON: They’re both terrific editors, and each brings their own flavor to the work. I’ve always wanted to feel as though my movies are progressing. Especially with the Resident Evil films, I never wanted the audience to think, Oh, it’s the same thing again. I wanted the movies to thematically, narratively, and visually have a sense of progression. So it was familiar material but presented in a completely different way. And the editing style is definitely a part of that. If you look at The Final Chapter, it’s dramatically different to the Resident Evil movies that Niven edited, and I felt that that was appropriate.

Having done two movies with Doobie, I thought that it would be fun to work with Niven again. The way I make my movies, we tend to shoot them in different places, and we also use the local crew. I travel very light. I’m not one of those directors who takes 30 or 40 people with them. I’ll take a director of photography, a visual effects supervisor, and an editor. And then pretty much everybody else is the local crew. Traveling light prevents—and I’ve seen it on other movies—a kind of them and us situation, where those coming in go, Oh, these locals don’t know what they’re doing, they don’t know how to make movies, and the locals see the incoming crew as a bunch of snobs who have it too good. Because then there’s friction. When there’s only a few of you going there, you really have to embrace the local crews, embrace their way of working, and then seek to inspire them.

Which is all a long and windy way of saying that while my visual effects supervisor and director of photography tend to be the same person, the editor is the only real place where I get to make a change in my core group. And I feel like that’s important for me to change up every so often. The really good editors are not the ones who do what they’re told, they’re the ones who challenge you. I like working with people who throw their ideas in and who don’t mind fighting for those ideas. Quite often you go through these struggles before realizing, Yeah, they’re right. I never want to be one of those directors who travel around in a bubble, where to get to them you have to go through all these other people. I like to be challenged, and I think I’m a very collaborative person. I have an eye, and I know what I want, but if someone has a good idea, I’m happy to take it off them… and then take credit for it.

In the Lost Lands (Paul W. S. Anderson, 2025).

NOTEBOOK: In the Lost Lands is marked by a series of magnificent widescreen master shots. This is your seventh film with cinematographer Glen MacPherson. Tell me a bit about your working relationship and your conversations about the film’s visual design.

ANDERSON: What I love about Glen is that he’s very adaptable. He’s a highly skilled director of photography. DPs, like actors and directors, tend to get typecast. Once you’ve done a certain type of film, people are like, Oh, he’s that guy, he does the dark scary movies, or the Michael Bay–style action movies. There’s a belief among producers and studio people that that guy can’t go and do something different. What I love about working with Glen is that people often come up to me and say, “The movie looks great. Who’s the new DP?”

If you look at the bright, polished look of Resident Evil: Retribution, for example, I said to Glen, “Let’s make it look like a perfume ad, but it’s an action movie!” He was like, “Well, um, that’s not in the American Cinematographer’s handbook. Let me have a think about that.” That was our approach: It has an incredibly slick feel, but it’s a kinetic action movie. And then the next Resident Evil looked completely different. We never stuck the camera on a tripod, everything was handheld. So it felt to a lot of people as though Doobie had cut it much faster than Niven had cut the previous one, and they assumed it must be a different cinematographer, but it was the same guy.

And then between Monster Hunter and In the Lost Lands, people are again asking, “who’s the new DP?” But what they’re really reacting to is that Monster Hunter was all shot on real, organic locations—I think we went indoors twice, and the crew lived in tents in Namibia and South Africa—whereas Lost Lands has a much more painterly feel to it. I always refer to it as the graphic novel that Hieronymus Bosch never got out of his system.

NOTEBOOK: Hieronymus Bosch with lens flares.

ANDERSON: Exactly. And a lot of people ask, “If Lost Lands is mostly visual effects, how important is the DP?” Well, the DP is very important. I don’t think I’ve ever talked with a DP more than I talked with Glen before shooting Lost Lands. Because we were creating the environments, and he was part of that. We’d have these discussions where we’d create the environments in Unreal, which is a very fast video-game engine, and Glen would say things like, “This is great but the sun shouldn’t be over there, it needs to be over here.” So you’d move the sun around 120 degrees in the sky, and then bring it down 30 degrees closer to the horizon. And the good thing about Unreal is that you can do that quite quickly. It’s not like you ask for it and then have to wait a week for someone to bring the visual effect back. And then everyone would say, “Oh wow, that looks amazing,” because Glen is now lighting these virtual sets as though they were real. And once we had worked out what made the virtual set look the best, that would become Glen’s roadmap for lighting the physical set.

Everything that the actors interacted with was real. So everything in the mid-ground and the foreground we built for real, and the deep backgrounds were these virtual environments. But because Glen and I had already worked on them, we’d know that this location is going to look great with the sun ten degrees off the horizon. So Glen would then put his main light ten degrees off the studio floor, allowing the studio environment and the digital environment to mesh together very well.

In the Lost Lands (Paul W. S. Anderson, 2025).

NOTEBOOK: In the years between the release of Retribution and The Final Chapter, you became something of a poster boy for a resurrected auteurism debate in online film circles. Were you aware of these conversations at the time?

ANDERSON: When I was growing up, as a teenage wannabe filmmaker, I have to say I wasn’t looking at British filmmakers for inspiration. British cinema at that time was heavily arthouse, or it was period. There was very little in the middle. So I started looking to other countries and other filmmakers as my role models. Obviously, the road led to America, but there were a lot of British directors who had gone to America, like the Scott brothers [Ridley and Tony] and Adrian Lyne. They were my idols.

Then, because I also wrote, I looked to Europe, because that’s where it felt like a lot of the writer-directors were. Wim Wenders is obviously a very different filmmaker to me, but back then I thought, God, his movies look really, really stylish, and on not-a-big budget. Shopping was achieved on a kitchen-sink drama budget, but we had car chases and helicopters and riot scenes. I remember when the reviews came out, some were disgusted. One said, ”Shopping is nothing but a reckless orgy of destruction.” I loved that quote, because I thought, Do you realize how expensive it is to put a reckless orgy of destruction on screen? It’s more money than we had, but we did it! I loved it so much that I had that quote put on the poster for the UK release.

It may have been the same journalist who said that Jude Law was too good-looking to be an actor. They also described me as painting in the same primary colors as someone like Luc Besson. To me, that was a huge compliment, being compared to a filmmaker who was working in the cinéma du look and was a respected auteur.

So to come back to your question, it’s definitely a compliment if someone wants to describe me as an auteur, and it’s something I’ve worked at. The movies I’m happiest with, and think have come out the best, are those on which I’ve done a lot of the heavy lifting. Either because I’ve written it myself, or because I’ve done a lot of work behind the scenes developing it for a long period of time. For me, the writing process becomes pre-pre-production. You’re thinking about what the movie will be, and how the movie will look, and how you’re going to put it together.

In the Lost Lands (Paul W. S. Anderson, 2025).

NOTEBOOK: Given the ambivalent views on artificial intelligence in the last two Resident Evil films, I’m curious about your perspective on AI as a filmmaking tool.

ANDERSON: Listen, it’s there and it’s being used. Some of it is fantastic. There are some Instagram Reels that I’m totally in love with. But then being able to deploy that imagery as a means of telling a story is much more challenging. It’s one thing to have snippets, but quite another to bend those snippets to your will to tell a story.

When you make a movie like Lost Lands that has as many visual effects as it does, you’re using AI. But AI is so broad, and so much of it is so bad, that what you really need is to curate it. The good use of AI is when it has been highly curated, and then worked upon by a visual artist afterwards. Those are the kind of AI-led images that I like in the work I’ve done. I think it can only get you so far, and then you need a human being with great taste to push it to the next level.

That’s what AI doesn’t have. It doesn’t have the taste button yet. It can do a whole bunch of stuff, but unless you have human beings pushing it to the next level, it’s not something I would want to stick in one of my movies, that’s for sure.

![‘Yellowjackets’ Stars on Filming [SPOILER]’s ‘Heartbreaking’ Death in Episode 6 and Why It Needed to Happen That Way](https://variety.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/Yellowjackts_306_CB_0809_1106_RT.jpg?#)

![‘Silent Hill f’ Announced for PlayStation 5, Xbox Series and PC; New Trailer and Details Revealed [Watch]](https://bloody-disgusting.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/silenthillf-1.jpg)

![‘The Astronaut’ Review: Kate Mara Is Trapped In A Sci-Fi Horror That Crashes to Earth [SXSW]](https://cdn.theplaylist.net/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/13233357/the-astronaut-321845-kate-mara.jpg)

![[FINAL WEEK] Platinum Status And 170,000 Points: IHG’s New $99 Credit Card Offer Worth Getting And Keeping](https://viewfromthewing.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/IMG_3311.jpg?#)

.jpg)

![[Podcast] Should Brands Get Political? The Risks & Rewards of Taking a Stand with Jeroen Reuven](https://justcreative.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/jeroen-reuven-youtube.png)