The Action Scene | Bruising Banality in Steven Soderbergh’s “Haywire”

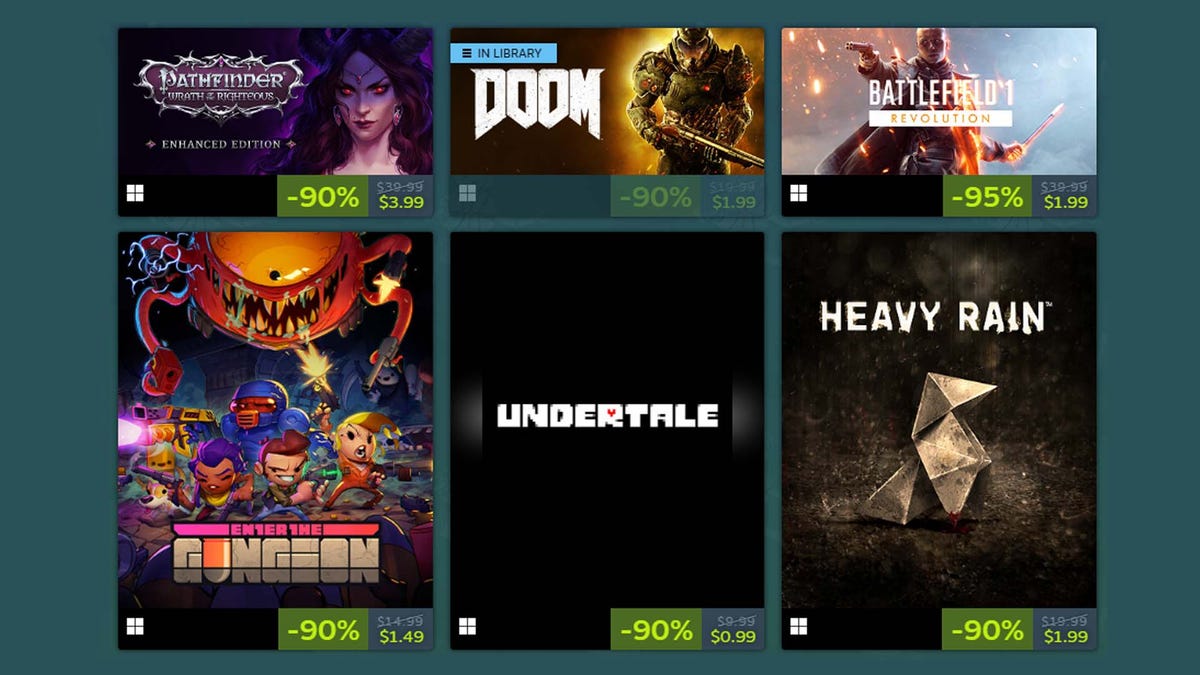

Haywire (Steven Soderbergh, 2011).Violence erupts in a sleepy Upstate New York diner at the start of Steven Soderbergh’s Haywire (2011). Seated in the back, Mallory Kane (Gina Carano) is joined by her hungover, bleary-eyed associate Aaron (Channing Tatum), who has been sent to pick her up. She refuses to budge. As Aaron is served his coffee, the camera peers at them from a few yards away, peeking around the counter at knee height, like an eavesdropping waitress wiping up spilled food. He feigns a sip, then abruptly pitches the cup’s scalding contents at Mallory. She clutches her face in pain, but no reaction shot follows: the camera retains its distant vantage on the pair, off-center in the frame, as if it, too, hasn’t fully processed this jolting disruption of a banal scene.Aaron breaks a glass against Mallory’s temple, causing her to keel over onto the floor. The brawl now begins in earnest. The pace of cutting accelerates as blows are exchanged, but the tone remains muted. There’s no music, only the sounds of the scuffle: grunts, kicks and punches muffled by fabric, the tinny clang of Aaron’s head connecting with a metal barstool. Every maneuver is cleanly framed, enhancing a sense of real physicality, of a fight actually unfolding on camera; gunshots boom like cannons within such a confined space. The choreography is slick yet messy, involving tactical takedowns but also flailing and fumbling, especially when a couple of bystanders try to help subdue Aaron. Kept in frame throughout most of the fight, their stunned reactions cuing and mirroring our own, these onlookers are our diegetic counterparts. Like them, our humdrum day has been shockingly interrupted by spectacular action, a spike in the flatline.A spike in the flatline. Haywire (Steven Soderbergh, 2011).Leaving Aaron out cold and with a broken arm, Mallory flees in the car of one of the diner patrons (Michael Angarano). The presence of this bewildered outsider motivates an extended flashback, during which it’s revealed that Mallory once worked black ops for a private intelligence firm headed by her ex-boyfriend Kenneth (Ewan McGregor). Early in the flashback, we see a closed-door meeting in which a CIA agent named Coblenz (Michael Douglas) contracts Kenneth to complete a mission in Barcelona. Watch the exchange in isolation, however, and you wouldn’t know that this was what was happening. “This fee structure is unacceptable,” Kenneth remarks while leafing through a stack of forms. Pressed to elaborate, he continues: “We need to adjust the overall payment, in order that we can address things like hazard bumps. I’ll make a list. But also how the installments are spaced.”Yellow-tinted and set in a dingy conference room, the scene displays the trappings and language of finance culture, from the sight of businessmen talking payment plans (Douglas’s casting conjures Gordon Gekko and Wall Street malfeasance) to the flattening of embodied risk into legalese like “hazard”; similarly sanitized terms like “essential element” and “personnel” are used in a later meeting to describe Mallory, whom Coblenz wants to spearhead the operation (“I don’t want your B-team. She’s value-added”). Intercut with the meeting footage are flash-forward shots of her in the field, prepping the Barcelona job. From the outset, the film juxtaposes suits in offices with boots on the ground, data sheets with real-world danger—a contrast underscored by the diner fight, which accentuates the bruising materiality of bodies in pain and peril. This tension comes to a head when Mallory is framed for an assassination, for which the Barcelona job—ostensibly a rescue operation—was mere pretext.Kenneth (top) meets with Coblenz and a Barcelona contact, played by Antonio Banderas (bottom). Haywire (Steven Soderbergh, 2011).Variations on this premise appear in sundry spy thrillers. Haywire’s innovation lies in context and style. Released in the wake of the 2008 financial crisis, the film is part of a spate of pictures directed by Soderbergh that focus on precarious employment, institutional pressure, or both, from Bubble (2005) and its vision of economic stagnation in a small Midwestern town; to The Girlfriend Experience (2009) and Magic Mike (2012) and their portraits of job insecurity within the post-Recession gig economy; to works like Unsane (2018), High Flying Bird (2019), and Kimi (2022), which depict characters at the mercy of organizations like sports agencies and tech corporations.One of Hollywood’s premier experimenters in digital video, Soderbergh put the format to evocative use in several of these movies, crafting images that feel both workaday and artificial. Often centering on drab corporate spaces like offices (High Flying Bird), hospitals (Unsane), and health clubs (The Girlfriend Experience), these images flatly observe the rote rhythms and textures of life under capitalism, but, in their conspicuously digital, at times surveillant aesthetic, they also thematize the act of techno

Haywire (Steven Soderbergh, 2011).

Violence erupts in a sleepy Upstate New York diner at the start of Steven Soderbergh’s Haywire (2011). Seated in the back, Mallory Kane (Gina Carano) is joined by her hungover, bleary-eyed associate Aaron (Channing Tatum), who has been sent to pick her up. She refuses to budge. As Aaron is served his coffee, the camera peers at them from a few yards away, peeking around the counter at knee height, like an eavesdropping waitress wiping up spilled food. He feigns a sip, then abruptly pitches the cup’s scalding contents at Mallory. She clutches her face in pain, but no reaction shot follows: the camera retains its distant vantage on the pair, off-center in the frame, as if it, too, hasn’t fully processed this jolting disruption of a banal scene.

Aaron breaks a glass against Mallory’s temple, causing her to keel over onto the floor. The brawl now begins in earnest. The pace of cutting accelerates as blows are exchanged, but the tone remains muted. There’s no music, only the sounds of the scuffle: grunts, kicks and punches muffled by fabric, the tinny clang of Aaron’s head connecting with a metal barstool. Every maneuver is cleanly framed, enhancing a sense of real physicality, of a fight actually unfolding on camera; gunshots boom like cannons within such a confined space. The choreography is slick yet messy, involving tactical takedowns but also flailing and fumbling, especially when a couple of bystanders try to help subdue Aaron. Kept in frame throughout most of the fight, their stunned reactions cuing and mirroring our own, these onlookers are our diegetic counterparts. Like them, our humdrum day has been shockingly interrupted by spectacular action, a spike in the flatline.

A spike in the flatline. Haywire (Steven Soderbergh, 2011).

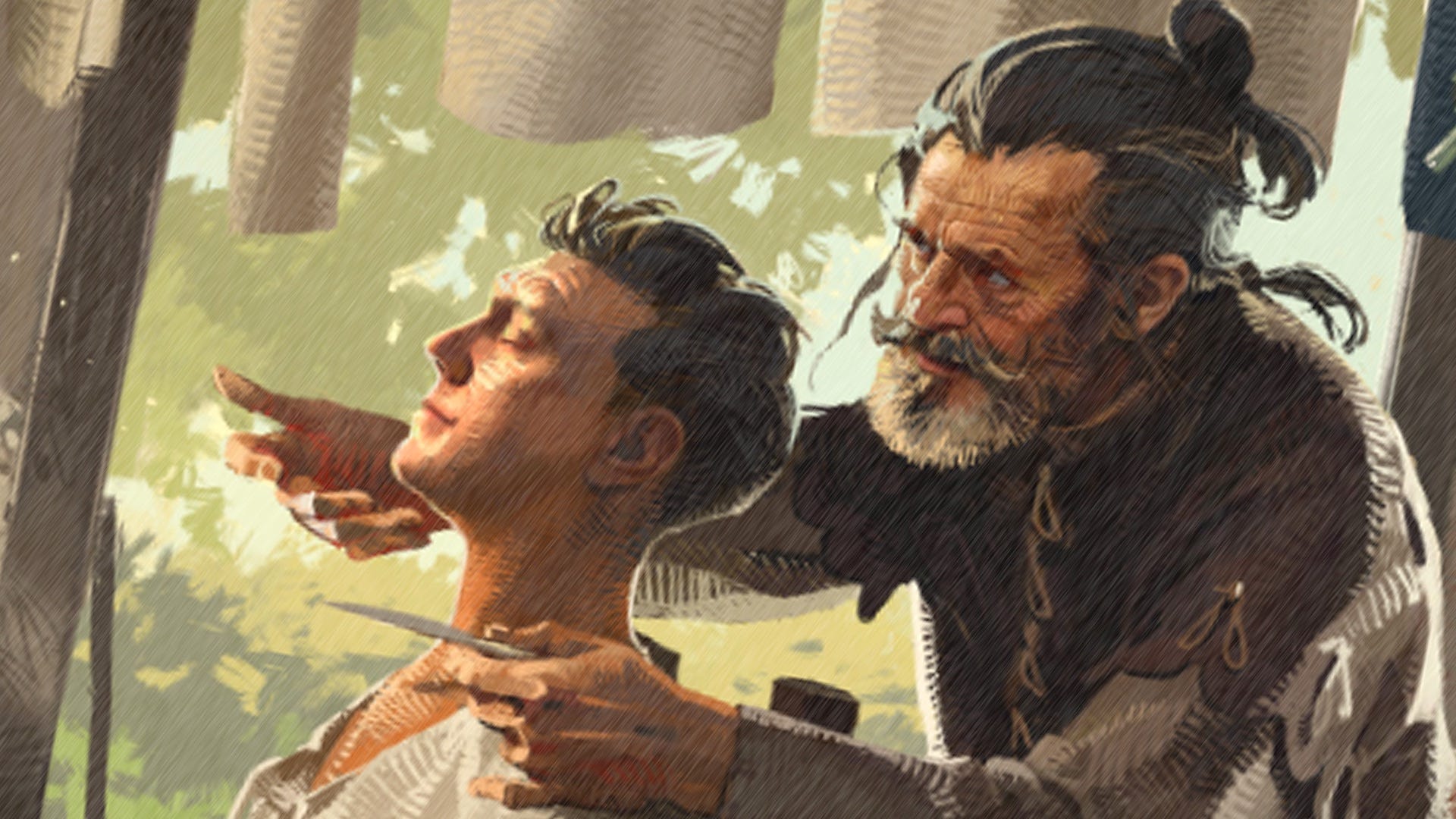

Leaving Aaron out cold and with a broken arm, Mallory flees in the car of one of the diner patrons (Michael Angarano). The presence of this bewildered outsider motivates an extended flashback, during which it’s revealed that Mallory once worked black ops for a private intelligence firm headed by her ex-boyfriend Kenneth (Ewan McGregor). Early in the flashback, we see a closed-door meeting in which a CIA agent named Coblenz (Michael Douglas) contracts Kenneth to complete a mission in Barcelona. Watch the exchange in isolation, however, and you wouldn’t know that this was what was happening. “This fee structure is unacceptable,” Kenneth remarks while leafing through a stack of forms. Pressed to elaborate, he continues: “We need to adjust the overall payment, in order that we can address things like hazard bumps. I’ll make a list. But also how the installments are spaced.”

Yellow-tinted and set in a dingy conference room, the scene displays the trappings and language of finance culture, from the sight of businessmen talking payment plans (Douglas’s casting conjures Gordon Gekko and Wall Street malfeasance) to the flattening of embodied risk into legalese like “hazard”; similarly sanitized terms like “essential element” and “personnel” are used in a later meeting to describe Mallory, whom Coblenz wants to spearhead the operation (“I don’t want your B-team. She’s value-added”). Intercut with the meeting footage are flash-forward shots of her in the field, prepping the Barcelona job. From the outset, the film juxtaposes suits in offices with boots on the ground, data sheets with real-world danger—a contrast underscored by the diner fight, which accentuates the bruising materiality of bodies in pain and peril. This tension comes to a head when Mallory is framed for an assassination, for which the Barcelona job—ostensibly a rescue operation—was mere pretext.

Kenneth (top) meets with Coblenz and a Barcelona contact, played by Antonio Banderas (bottom). Haywire (Steven Soderbergh, 2011).

Variations on this premise appear in sundry spy thrillers. Haywire’s innovation lies in context and style. Released in the wake of the 2008 financial crisis, the film is part of a spate of pictures directed by Soderbergh that focus on precarious employment, institutional pressure, or both, from Bubble (2005) and its vision of economic stagnation in a small Midwestern town; to The Girlfriend Experience (2009) and Magic Mike (2012) and their portraits of job insecurity within the post-Recession gig economy; to works like Unsane (2018), High Flying Bird (2019), and Kimi (2022), which depict characters at the mercy of organizations like sports agencies and tech corporations.

One of Hollywood’s premier experimenters in digital video, Soderbergh put the format to evocative use in several of these movies, crafting images that feel both workaday and artificial. Often centering on drab corporate spaces like offices (High Flying Bird), hospitals (Unsane), and health clubs (The Girlfriend Experience), these images flatly observe the rote rhythms and textures of life under capitalism, but, in their conspicuously digital, at times surveillant aesthetic, they also thematize the act of technological capture itself: the ensnarement of these characters within larger institutional structures that “frame”—constrain, confine, determine—the form that the “mundane” takes. Within this context, the mundane signals a reality that has been actively shaped: routinized and banalized into simply “how things are,” while the forces behind it remain abstracted, mysterious, and seemingly untouchable.

Digital banality. Top: The Girlfriend Experience (Steven Soderbergh, 2009). Bottom: Unsane (Steven Soderbergh, 2018).

In Haywire, a film about lower-level workers paying the price for upper management’s schemes, it’s striking that the action scenes—which almost exclusively involve the former group—are so bracingly naturalistic. Through its emphatically muted fights, the film invites us to feel the weight of banality, to consider where the pressure is coming from and who bears the brunt of the burden. This approach marks a radical departure from the Bourne-style action filmmaking that was fashionable in the late aughts and early 2010s, in which rapid cutting and jittery, handheld camerawork evoke the flitting eyes and racing mind of super agents outsmarting and outmaneuvering their opponents. For such characters, taking action means beating the system at its own game, becoming more in sync with its logic of surveillance and split-second calculation than those in power.

Haywire’s fights forego this kind of formal agitation, opting instead for a sense of inertia, of business as usual. Ironically, the violence hits harder due to the everyday context; the action feels unusually jolting, like we’re being forced to sprint without having warmed up. Conversely, the everyday is also defamiliarized by the violence, which strains the fabric of the quotidian, foregrounding its texture and density. A similar defamiliarization of the mundane occurs in Soderbergh’s other Recession-era films, but Haywire differs in one respect: It’s an action movie. Through its set pieces, the idea of bodies under pressure is dramatized in an especially visceral way. Choreographed by veteran stunt coordinator J. J. Perry, who makes a brief cameo as one of Kenneth’s cronies, the fights pummel and galvanize the viewer’s own body, making them feel more vividly the heaviness of suppressive banality and the act of resisting it.

Combat tinged with the risqué. Haywire (Steven Soderbergh, 2011).

Haywire’s other big fight takes place in a hotel room. Returning from a dinner-party-cum-reconnaissance-mission, Paul (Michael Fassbender), an agent posing as Mallory’s husband, tries to kill her on Kenneth’s orders. Opening with the same kind of abrupt violence and aloof visual framing that kicked off the diner brawl—here, a sharp crack of his fist against the nape of her neck, viewed in a mostly static long shot—the scene observes as the pair tussle from living room to bedroom, wrecking the decor in the process.

If the diner fight was uncompromisingly blunt, this one contains a hint of playfulness. Mussed-up hair, a bared shoulder, heavy breathing, a triangle choke executed in bed with stockinged legs—it’s combat tinged with the risqué, of the sort one might expect from the director of Out of Sight (1998) and the Ocean’s movies (2001–07). And yet, for a film about bodies being flattened into “value added,” the sensual fullness of the combatants also feels revelatory, asserting these capitalist subjects as unruly, irreducible, uncontainable. Break the rules, fight back, affirm your existence. Go haywire.

![‘Silent Hill f’ Announced for PlayStation 5, Xbox Series and PC; New Trailer and Details Revealed [Watch]](https://bloody-disgusting.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/silenthillf-1.jpg)

![Final Pre-Sale Campaign Launched for ‘TerrorBytes: The Evolution of Horror Gaming’ [Trailer]](https://bloody-disgusting.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/terrorbyteslogo.jpg)

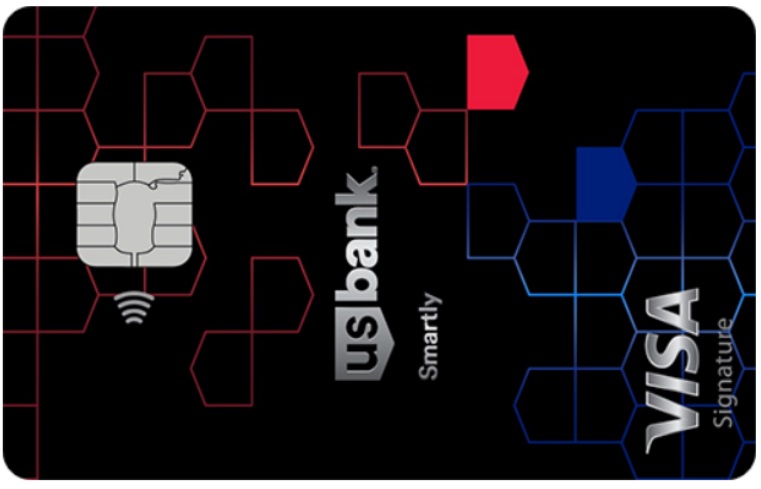

![[FINAL WEEK] Platinum Status And 170,000 Points: IHG’s New $99 Credit Card Offer Worth Getting And Keeping](https://viewfromthewing.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/IMG_3311.jpg?#)

.jpg?width=1920&height=1920&fit=bounds&quality=80&format=jpg&auto=webp#)

![[Podcast] Should Brands Get Political? The Risks & Rewards of Taking a Stand with Jeroen Reuven](https://justcreative.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/jeroen-reuven-youtube.png)