Duke Johnson on Charlie Kaufman’s Advice and the Philosophies of Identity That Guide The Actor

After co-directing 2015’s Anomalisa with Charlie Kaufman, Duke Johnson’s solo follow-up is an adaptation of the Donald E. Westlake’s novel Memory. Paul Cole (André Holland) is the eponymous actor––or so people tell him is his occupation after he wakes up in small-town Ohio with a mysterious head injury and zero memories. There’s a beautiful woman, […] The post Duke Johnson on Charlie Kaufman’s Advice and the Philosophies of Identity That Guide The Actor first appeared on The Film Stage.

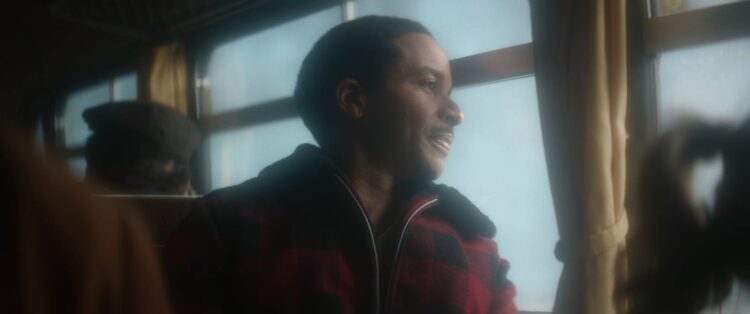

After co-directing 2015’s Anomalisa with Charlie Kaufman, Duke Johnson’s solo follow-up is an adaptation of the Donald E. Westlake’s novel Memory. Paul Cole (André Holland) is the eponymous actor––or so people tell him is his occupation after he wakes up in small-town Ohio with a mysterious head injury and zero memories. There’s a beautiful woman, Edna (Gemma Chan), and a small cast of characters who may or may not have Paul’s best interests at heart. It’s a classic noir setup, but Johnson is less interested in doling out narrative breadcrumbs that build into a perfectly interlocking narrative so that audiences can solve a central mystery––instead he centers us firmly within the headspace of Paul, prioritizing larger philosophical questions about identity along with a budding romance between Paul and Edna. Johnson was transfixed watching Chan deliver a monologue about lost love in Steven Soderbergh’s Let Them All Talk and casts her alongside a small host of fellow Brits. Many perform double-duty in multiple roles, which saved the small production money and creates a greater sense of disorientation for Paul as he struggles to gather his bearings.

Shot in a warehouse in Budapest and finished mostly by Johnson on his own dime utilizing his animation studio in Burbank, the production was, per him, “strange and unconventional” and very collaborative with the 15-person acting troupe. As the film enters theaters via NEON, I spoke with Johnson over Zoom about the key advice Charlie Kaufman gave him on trusting his instincts and the power of open artifice and metaphor.

The Film Stage: After Anomalisa, did you experience any industry resistance moving to a live-action film? It’s an industry with a reputation for pigeon-holing.

Duke Johnson: Ironically, no. I absolutely anticipated that, and that’s part of the reason why I wanted to use the momentum created by Anomalisa to do a live-action film. I wasn’t offered live-action movies after Anomalisa, but I was offered lots of opportunities for mainstream, family-animated films. It’s funny how people could see a direct line more to me doing a Pixar movie––not that I was offered a Pixar movie, but that type of thing––after Anomalisa, rather than something like The Actor, which, to me, makes more sense. But when I did go out with The Actor, I didn’t get any of that. In fact, the people at NEON were interested in what I would bring to the medium. I’ve never worked within a studio system and I always generate my own material, anyway. I have pitched for movies and not gotten them, so maybe that was in their mind––“This guy can’t do this”––but they didn’t say it to my face.

There’s a version of The Actor that’s more of a puzzle box for audiences to solve what happened to Paul. Instead the emotion of the story, specifically with Paul and Edna, is centralized. How did you balance those elements with this mystery of what happened to him?

Charlie Kaufman pitched the book to me. Not because he was trying to sell me the movie or anything; I was asking him to recommend a book. What he liked about it was this idea that it was by this famous crime author in the guise of a crime noir thriller that used the amnesia trope. But where it’s usually used to propel a plot, in this case, it was more a way to explore the nature of identity and more abstract or emotional ideas. That was my guiding force when making the film: I was drawn less to the idea of how we make this have twists and turns and the puzzle pieces will add up to something and more interested in exploring abstract ideas. André is so grounded in his emotions; they are very available to him. You just like him and root for him as a person. I felt I could explore more abstract ideas because he would be this grounding emotional force that takes you through the story.

Most of the movie is shot on stages, right?

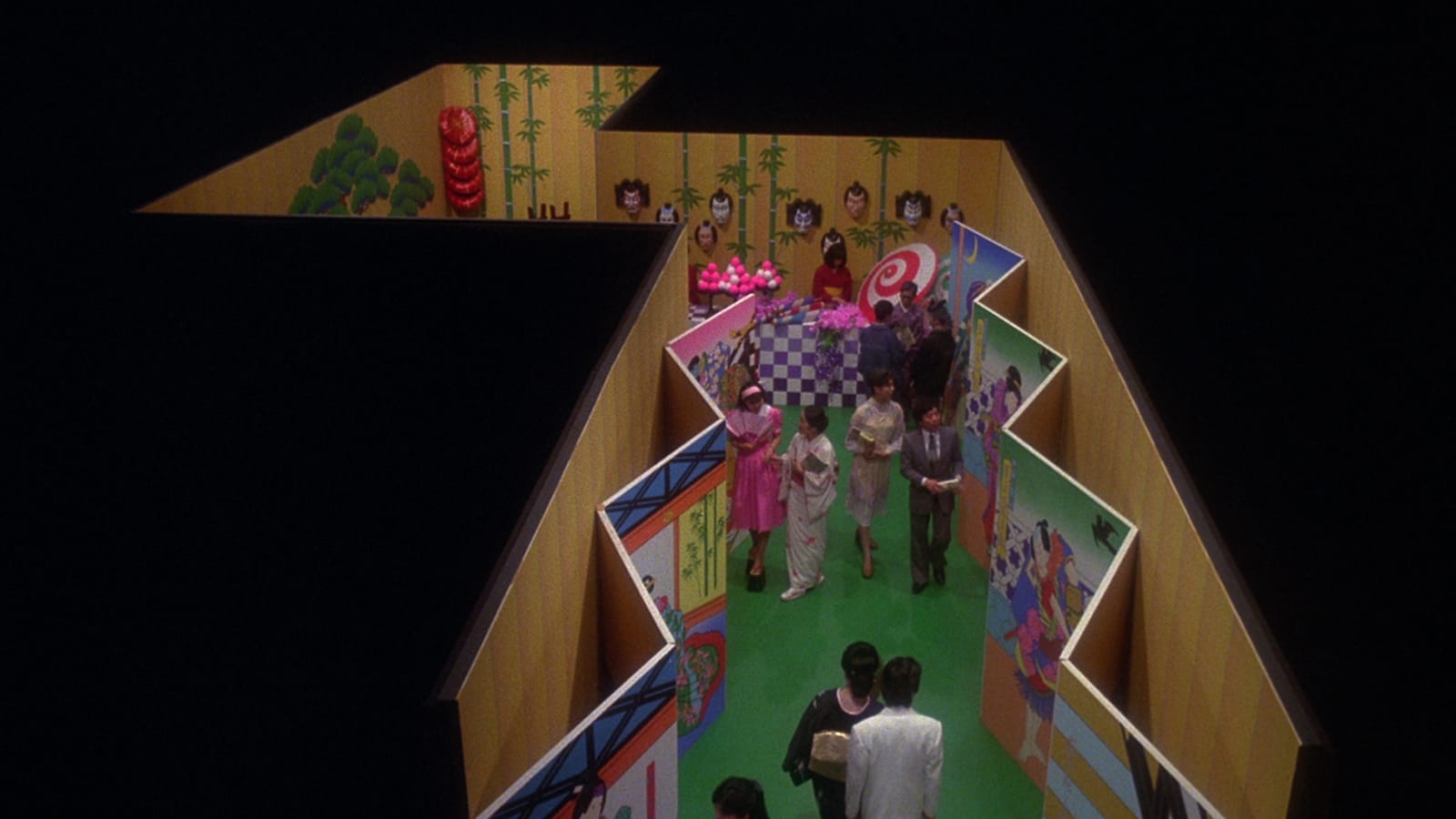

The book is very much an internal monologue of what this character’s emotional experience is; he’s talking in his head about everything. How do you make that into an audio-visual experience? I was interested in world-building because that’s what I like to do in animation. That’s something I’ve always loved about films––its world-building qualities. So I wanted to build a world that could illustrate the artifice and the construct and the visual and emotional metaphors of the film. We could reuse locations over and over and put people in the character’s mind of: “Have I been here before? Have I seen this before? Have I seen this person before?” But we were very low-budget, so it was a challenge. We ended up in a dank, dusty warehouse in Budapest in order to do that.

Duke Johnson, Gemma Chan, and André Holland at the premiere of The Actor

From what I understand, once you get within a certain budget range, especially when building sets, shooting in Eastern Europe allows your money to go a lot further.

They have the artisans, the labor, and material costs––everything. But we were so low-budget we couldn’t even afford a real sound stage. At one point, we’d be shooting and you’d hear metal beams dropping to the floor. We’d all be like, “Can everybody quiet on set? Can people stop dropping things?” And you eventually realize it’s just because you’re in a warehouse and things are shifting. It’s not soundproof. It was like Terry Gilliam’s Brazil––there was an added surreal, alternate-reality atmosphere.

When shooting low-budget on built sets, how do you keep the freedom to change things on the day of? Or do you just accept that this is the plan: “We spent a lot of time planning this, this is what we’re shooting.”

This was my first live-action feature, and part of what I learned was that you can’t approach it the same way you do an animated film. I did these animatics and had specific plans. This can be cost-effective when you’re building things because you can say, “I only need this one wall because I know what my shot is.” Then you show up, and live-action is its own beast. There’s this ticking clock. Those 12 shots you had planned, you have 45 minutes. You can’t do 12 shots. How can you get this scene in two shots or one shot? Then it’s all about flow state––you’re in it. What was helpful to me is that I had this troupe of 12 actors and then André, Gemma, and myself. So 15 people saying, “OK, what do we do? You could be over there, and we could do this, and I’ll cover it with this camera.” You have to have that flexibility. It almost doesn’t matter what your plan was because so much of filmmaking is problem-solving in the moment anyway––you just find a way through it.

I didn’t get everything I needed for the movie because we had a limited shooting schedule. That’s part of the reason the film took so long in post-production––I spent my time in the edit figuring out what else I needed to make the film work. I have my animation studio in Burbank with some stages. I did little animated shots and I had a friend of mine, who’s an incredible painter, do some matte paintings. I continued filling the holes and building the world for a long period of time, just on my own dime, afterwards. That’s why it took so long.

What do you feel drives audiences to this genre of memory loss? There’s a certain metaphor for a lot of different things that people can attach to it: Alzheimer’s, substance abuse, trauma. But in your mind, what do you think is the attraction to this narrative setup?

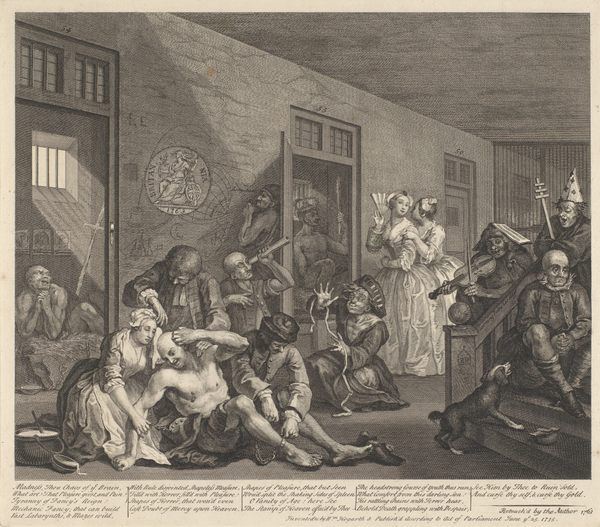

It’s existential dread. It’s mortality. We’re always searching for: who am I? Where do I fit in? Am I my thoughts? Everybody’s all Buddhismized these days, so we know we’re not our thoughts. That’s not who we are. But then, who am I? We did a lot of research just to have this infused in our brains––not that we’ve put these lessons in the movie or anything. It’s just exploring a research phase of the philosophies surrounding identity. There’s the metaphor of the mirror, which is that when you look in a mirror, you’re not the thing that’s reflected. You’re the thing that’s observing the thing reflected––these mindfuck concepts. What does that even mean?

A lot of philosophical ideology says that identity is tied to memory. That’s all you have that makes you who you are: the accumulation of your memories and your experiences. There’s also this idea that your personality is formed by trauma and through trial-and-error of experiences and interpersonal relationships. What if all that stuff was stripped away? And there’s the concept of: are you your actions? Are you what you’ve done? Can people change? Are you the worst thing that you’ve ever done? People want to think that they’re capable of change. Even people that do bad things or make a mistake want to say, “But I’m a good person.” What makes you a good person? Because you were an innocent child at some point? I have no answers to any of this––these are compelling ideas that are universal.

There is a humanist quality to the plot where, right off the bat, Toby Jones’ character gives Paul an advance payday loan. People don’t seem out to get Paul outright. Once again, there’s a version of this movie that goes in another direction that’s increasingly a nightmare because he doesn’t have any memories and can’t get help from anyone around him. Was that humanism in the source material or something that you developed?

There’s an element of paranoia that comes from him in the novel. There are questions of: are these mundane interactions, or is there something underlying? I wanted some of that tension to come out of characters playing multiple roles––that there’s something happening under the surface, on a deeper level in the world. How much of our perception is a construct? How much of the world is a construct? There was something to me more insidious about the idea of it not being overt in that sense, where everybody is directly out to get them. It’s more that he himself is less and less capable of interacting with a normal world. But then, at the same time, life is hard for everybody and human interactions of all kinds are difficult. I wanted it to be more about seeking connection than about surviving an agenda of everybody’s out to get them.

Was there ever a plan to shoot this in a more traditional way––in a small town in Ohio, for instance? Or did you always envision it shot on a constructed sound stage?

I’m sure there was a time early on when I pictured it that way. To me, with filmmaking, the form matches content, and I am drawn to narratives that have fantastical elements that are grounded emotionally. I come to filmmaking from a fine-art background. I love theater. I love the ballet. I’d rather see an oil painting than a photograph. Honestly, I feel within art that’s seeking some truth about the human experience, within the craft of the artistry, the artist’s soul becomes visible to a certain degree. It’s like the brush strokes in a painting. You can feel the energy with which it was painted.

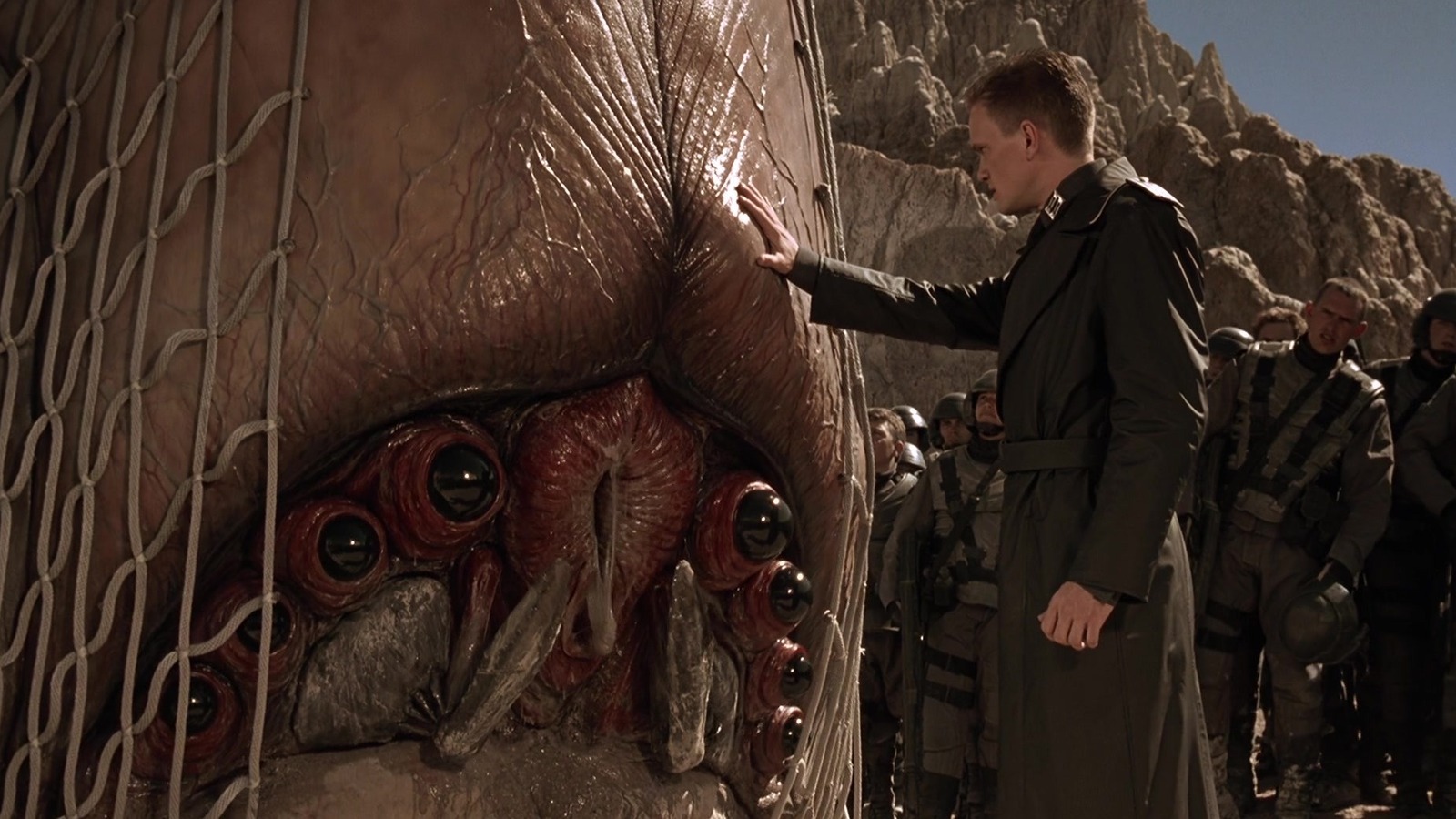

I’ve always been drawn to that aspect of filmmaking. Even when you watch older films, when they were trying to make it look real, you can often tell that it’s a set. In The Wizard of Oz, when they go marching down the yellow brick road, and they’re walking right up to a wall, and then the camera cuts before they hit the wall––I love that shit because it’s not the real world. They’re telling you a story. Through storytelling you see metaphors, and metaphors are an effective way to communicate universal human themes.

In Wes Anderson’s Asteroid City, the emotional climax is two actors standing on constructed balconies, talking about their characters’ roles in a scene we never see. It’s harder to achieve, but if you can elicit emotion within open artifice, it becomes a more powerful experience for audiences.

It is for me a lot of times, for sure.

Rather than some “realist” handheld experience.

Exactly. With Anomalisa we were playing a lot with the idea of, “OK, these are puppets.” And that’s funny and silly, in a way. Puppets are doing human things: they’re peeing and taking showers, and you can see puppet penises––ha, ha, ha. But are there moments where you forget that they’re puppets and you’re just with these characters? If you can do that, there’s something magical about that. That’s something that I like to play with.

Did you primarily cast British actors because it’s much easier for them to travel to Budapest, compared with Los Angeles actors, where it’s a nine-hour time difference?

100 percent. So much of this business is: the creative informs the practical, and the practical informs the creative. If you make a movie in L.A. you can’t afford to make sets, but every actor lives in L.A. and actors want to work––you might be able to get a bunch of amazing actors. You can’t do that in Budapest, because then you’re flying all these people out. Some actors fly private––it adds up real quick. But England: they speak the same language for American movies, and they can all do American accents. There’s so many talented artists there. It opens up the casting possibilities and your world.

You noted the process was a little experimental and unconventional. What do you mean, specifically?

I went to film school: NYU and then AFI. You only know as much as you know until you make something. Working in live-action, there’s a way that you do things. There’s a way that you do a budget. There’s a way that you do a schedule. There’s a way that you set up lighting structures––there’s just a way that you do it. And if you want to do things differently––“Why can’t we do it like this?”––there’s a thousand people that show up out of nowhere and go, “Well, that’s not how you do things in live-action. We have ways that we do things, and we don’t do it like that.”

I mentioned Charlie because he’s a mentor to me. We made that movie together and he’s a dear friend––somebody I admire greatly. He’s a brilliant man. He told me, “Don’t let anybody tell you you have to direct a certain way. Know that you can direct any way that you want to. You get to be any kind of director you want.” But immediately people are like, “You can’t do that, you can’t do that, you can’t do that.” It’s hard, and some of those battles you lose or you give into––and every time you do that, it’s a mistake. What makes art work, when it does work, is because you’re driven by some intuitive through line and you have to be able to follow it. When people get behind that and they support it, you can make new discoveries.

Did you witness Charlie Kaufman on the set of Anomalisa doing this?

Charlie is incredibly brave. He tight-ropes without a net and he’s not worried about it. He’s in pursuit of whatever he’s interested in creatively, and if people are like, “Maybe that’ll be perceived this way,” he responds, “Why are we worried about that?” With Anomalisa, for example, we had a friends-and-family screening and we showed the film in a rougher state, but basically what it is. We put on a questionnaire: “Was there any part of the movie that felt slow?” Almost everybody said: “Well, I guess the 20 minutes when he’s alone in the hotel room before Lisa shows up got a little slow.” So I, a young filmmaker: “Oh shit, people are bored.” I came back and was like, “We can cut this up. Let’s tighten it up. Let’s punch up those 20 minutes.” Charlie was like, “Well, wait a minute. When the audience has that experience, and then Lisa shows up, they’re going to have the same experience that he’s having where they’re gonna be like, ‘Oh, my God, something new. Something’s happening.’” He had the courage to say, “Let’s just ignore that. I believe that this is the right way to do it.” And he was right.

The Actor is now in theaters.

The post Duke Johnson on Charlie Kaufman’s Advice and the Philosophies of Identity That Guide The Actor first appeared on The Film Stage.

![First-Person Psychological Horror Title ‘The Cecil: The Journey Begins’ Arrives on Steam April 3 [Trailer]](https://i0.wp.com/bloody-disgusting.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/cecil.jpg?fit=900%2C580&ssl=1)

![‘It Ends’ Review: The Kids Are Not Alright In Alex Ullom’s Evocative Existential Horror Debut [SXSW]](https://cdn.theplaylist.net/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/12223138/it-ends-sxsw.jpg)

![Silver Airways Can’t Pay for Planes—So It’s Firing Pilots Instead [Roundup]](https://viewfromthewing.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/01/silver-airways.jpg?#)

![[FINAL WEEK] Platinum Status And 170,000 Points: IHG’s New $99 Credit Card Offer Worth Getting And Keeping](https://viewfromthewing.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/IMG_3311.jpg?#)

.jpg?#)

![[Podcast] Should Brands Get Political? The Risks & Rewards of Taking a Stand with Jeroen Reuven](https://justcreative.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/jeroen-reuven-youtube.png)