Show and Tell: Inside The Exhibition Highlighting The Art of Storyboarding

A new exhibition in Milan sheds light on the multiplicity of collaborative processes in the filmmaking world through the preliminary drawings developed for Psycho, Train to Busan, Wings of Desire and beyond. The post Show and Tell: Inside The Exhibition Highlighting The Art of Storyboarding appeared first on Little White Lies.

Cinema is an art that has a fair share of science behind it. However brilliant they may be, an individual’s ideas need to be realised by a team with diverse technical expertise. For many filmmakers, it is a matter of pathfinding, and storyboards are often solicited to mediate between creativity and practicality, ensuring their abstract thoughts are understood, and then acted on in a production.

Such is the focus of the ongoing exhibition ‘A Kind Of Language’ (on show till 8 September 2025) at Fondazione Prada’s Milanese gallery Osservatorio, curated by Melissa Harris, formerly editor-in-chief of the esteemed photography magazine Aperture. The 56 sets of storyboards on display, some dating back to the 1920s, exemplify the liminal nature of the graphic device and its propensity to shapeshift in the hands of different directors.

Even though not every director adopts it, storyboarding has been a cornerstone of the industry for the majority of its existence. Georges Méliès was among the forerunners who incorporated it into his whimsical works, such as in A Trip to the Moon where the intricate camerawork and special effects qualified the film as an ambitious production during the 1900s. The director made rigorous plans, among those series of preparatory sketches, ahead of time to coordinate all the moving parts.

More concerted effort to institutionalise storyboarding into the workflow came in the 1930s, when Walt Disney Studios consistently fleshed out plots and characters with detailed illustrations, as evidenced by the beautifully crafted panels for Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs (1937) and Fantasia (1940) in the exhibition.

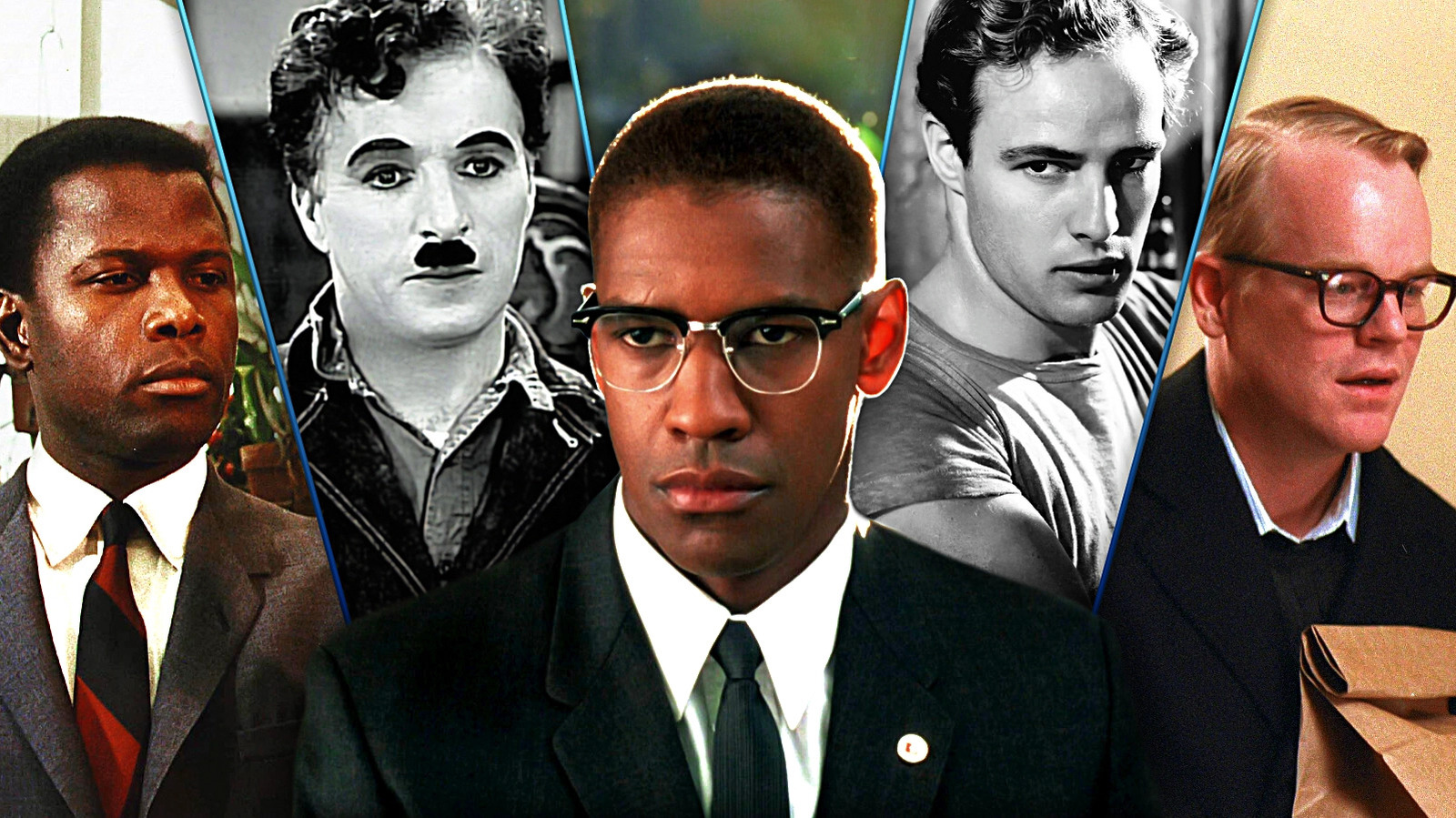

Since then, the practice was gradually popularised across Hollywood, and a common perception of it – sequential images visualised in boxes of the same size to map out the progression of a film – started to emerge among the public. ‘A Kind Of Language’, with its exhibits manifesting a breadth of visual styles, narrative structures and applications, problematises the notion that storyboards can or should be distilled to just one formula. From the hundred-page “story-bible” for Train to Busan detailing each frame with clear instructions, to the single large-scale rendering of Manderley for Alfred Hitchcock’s Rebecca, Harris emphasises that there really is not a fixed pattern in storyboarding. Each board is a means to an end, developed in response to the challenges around a specific title.

“One thing about the process that is especially interesting, is the lack of uniformity. When a director makes a storyboard, or commissions a storyboard artist, they’re on a journey,” she explained. “The storyboards represent moments of intuition and emotion, and address problems to be resolved, and at times might even show sequences that don’t end up in the final project. There’s a certain intimacy to them.”

The curator resists organising the storyboards by theme, time period or any obvious order. Instead, visitors are asked to connect with – and confront – the pieces individually. The resulting viewing experience is akin to a process of mental deconstruction: breaking up the memories we gathered from watching the films in a theatre, matching them with the sketches of the same films in printed form, and using them to comb through the logic behind the directors’ decisions.

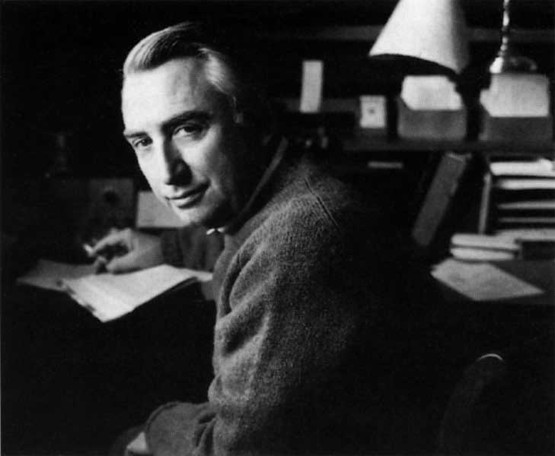

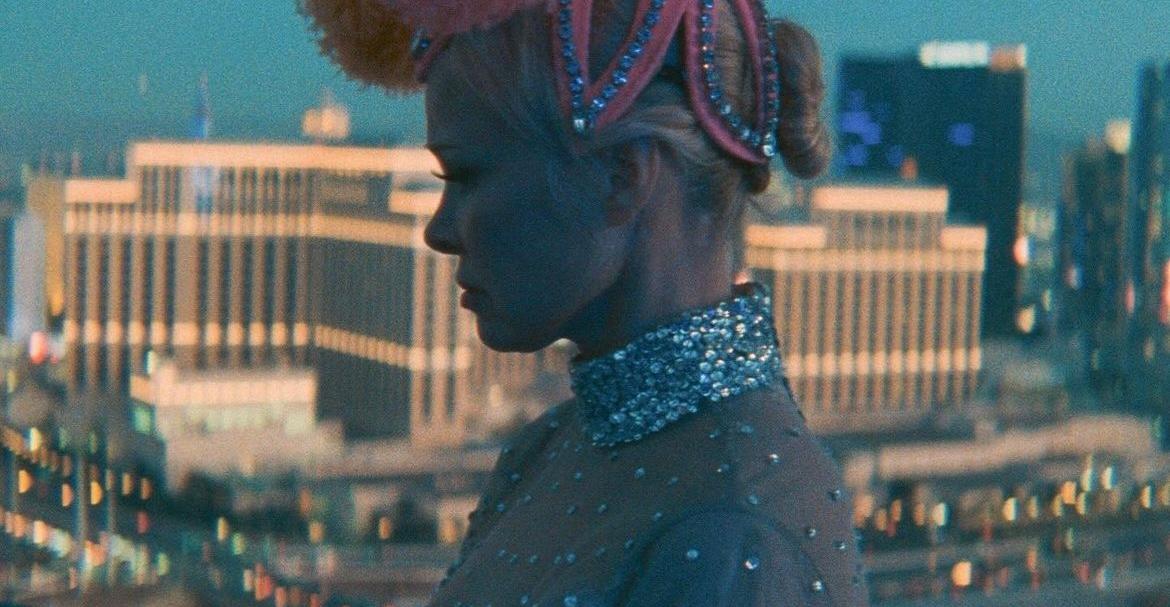

The thought exercise is not unlike how the actors, set designers, editors and other personnel involved in a film production assess the boards, picturing, digesting and adding to the director’s vision. This is especially apparent in the storyboards for Close Encounters of the Third Kind and Jodorowsky’s unrealised version of Dune from the 1970s. Executed in distinct styles, they let the projects’ collaborators in on the fantastical settings with few reference points in reality, or in the case of the gestural drawings for Wings of Desire, the surreal elements heightening the Wim Wenders’ subjective sentiments towards Berlin.

In a later interview, Wenders elaborated on the way he mobilised different sets of preliminary materials spontaneously during filming. “The film was largely done without a script… The script was a huge wall in my office with all the places in Berlin I wanted to shoot. On the other side of the room, I had all the scenes that we could possibly shoot,” he said. “Every night I was picking a scene, and then I was looking for the place where it could happen.”

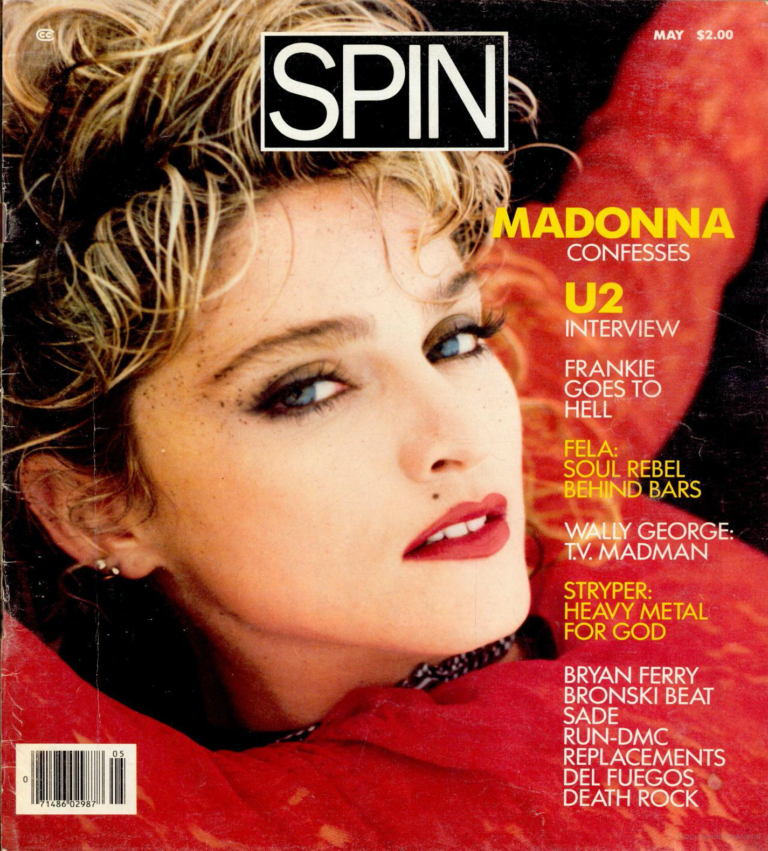

Another task storyboards excel at is capturing the depth of specific scenes and characters. Saul Bass, for instance, detailed the shower sequence of Psycho with a frame-by-frame outline. It accentuates Marion Crane’s fear as the images’ focus shifts across her hands, feet, eyes and face, which was recreated vividly by Janet Leigh. Bass admitted Alfred Hitchcock was taken aback by the board’s claustrophobic mood and quick cutting at first, but after he did a test run with Leigh’s stand-in following his design and showed the edited clip to the director, Hitchcock finally gave his green light to the proposal. “It was an amazing moment… I set up each shot, matching them to the storyboard,” Bass said.

Meanwhile, the graphic portfolio for the Indian film Anjuman serves as a freeform character study, integrating vignettes of the protagonists’ facial expressions in different scenarios and literal remarks of their traits in an organic manner. There are endless ways to play around the format, always contingent on what requires attention, who needs to be informed, and when decisions are made.

“This kind of exchange between collaborators can take place before production begins. And the storyboards may be used to convince various individuals to participate in a project,” Harris adds. “It’s a unique form of communication, and we think the name of the exhibition ‘A Kind Of Language’ really reflects that.”

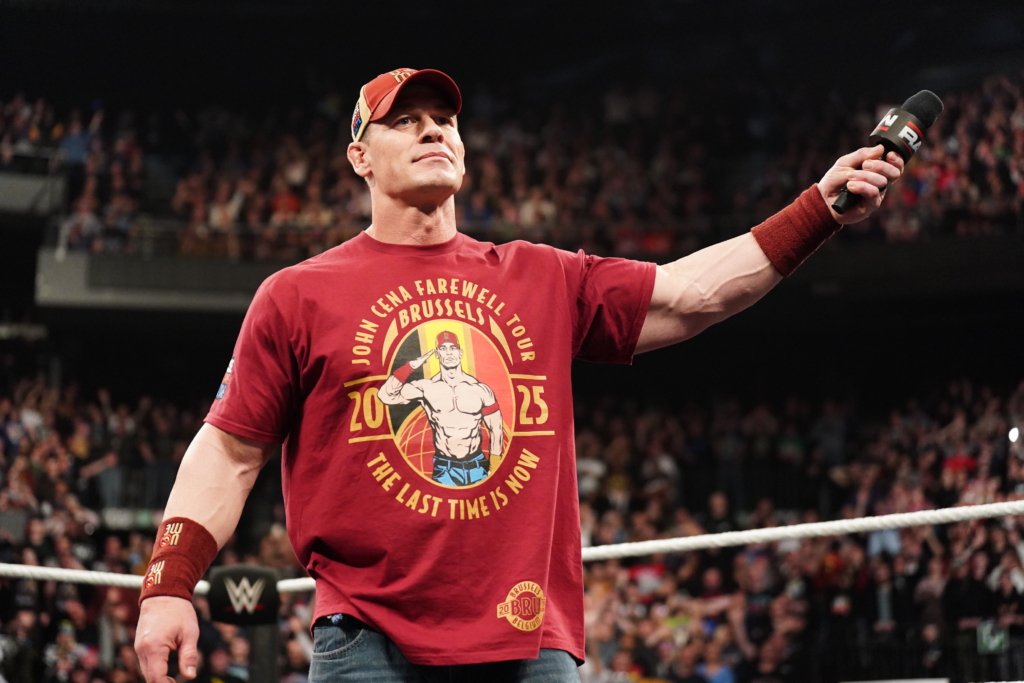

One of the exhibits that naturally stands out is the animatic storyboard produced by Jay Clarke and Edward Bursch for The Grand Budapest Hotel which highlights technology’s role in reinventing the storyboarding process. For a director whose works stand out for the meticulous scene composition, being able to predict how his characters and spaces move against one another gave Wes Anderson a leg up.

Looking forward, artificial intelligence seems to be an inevitable agent to disrupt the practice. To what extent? Time will tell. But Harris hopes the essence of storyboarding will remain intact. “I’d go back to the journey analogy. You’d want to get to the destination in your own way, at your own pace,” she says. “It makes the journey poetic and powerful, and you’ll likely end up with something interesting.”

The post Show and Tell: Inside The Exhibition Highlighting The Art of Storyboarding appeared first on Little White Lies.

![Underwater FPS ‘Chasmal Fear’ Surfaces on Steam April 17 [Trailer]](https://bloody-disgusting.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/chasmal.jpg)

![Battle Hordes of Alien Horrors in Survival Shooter ‘Let Them Come: Onslaught’ [Trailer]](https://bloody-disgusting.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/letthemcome.jpg)

![Inside the Vault [on SPIONE]](http://img.youtube.com/vi/gOltBk-9-rU/0.jpg)

![Please Watch Carefully [THE HEART OF THE WORLD]](http://www.jonathanrosenbaum.net/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/the-heart-of-the-world-5-300x166.jpg)

![Passenger Pops Open Champagne Mid-Flight—That Didn’t Go Over Quietly [Roundup]](https://viewfromthewing.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/passenger-pops-champagne.jpg?#)

.jpg?width=1920&height=1920&fit=bounds&quality=80&format=jpg&auto=webp#)

![[Podcast] Should Brands Get Political? The Risks & Rewards of Taking a Stand with Jeroen Reuven Bours](https://justcreative.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/jeroen-reuven-youtube-1.png)

![[Podcast] Should Brands Get Political? The Risks & Rewards of Taking a Stand with Jeroen Reuven](https://justcreative.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/jeroen-reuven-youtube.png)