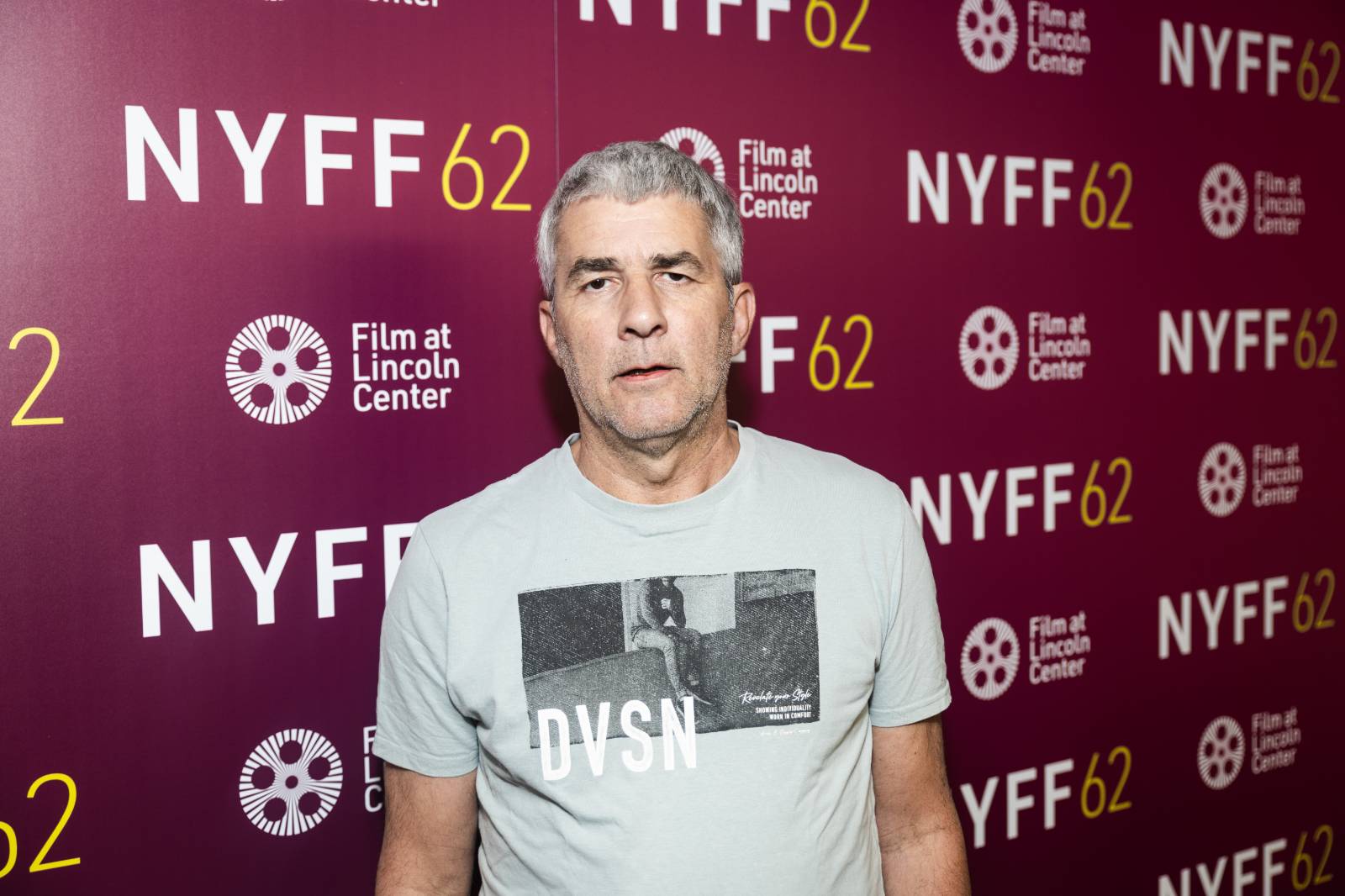

Alain Guiraudie on Misericordia, Desiring His Actors, and Praise from Godard and Bret Easton Ellis

If Alain Guiraudie has still not quite transcended festival obscurity to become an American art-house staple, all the more credit to the films––they’ve never approached niceties, comfortability, or a distillation of bleak perspectives for co-production amenability. But if anything must break through, Misericordia might as well be the one: ten months after its Cannes debut, […] The post Alain Guiraudie on Misericordia, Desiring His Actors, and Praise from Godard and Bret Easton Ellis first appeared on The Film Stage.

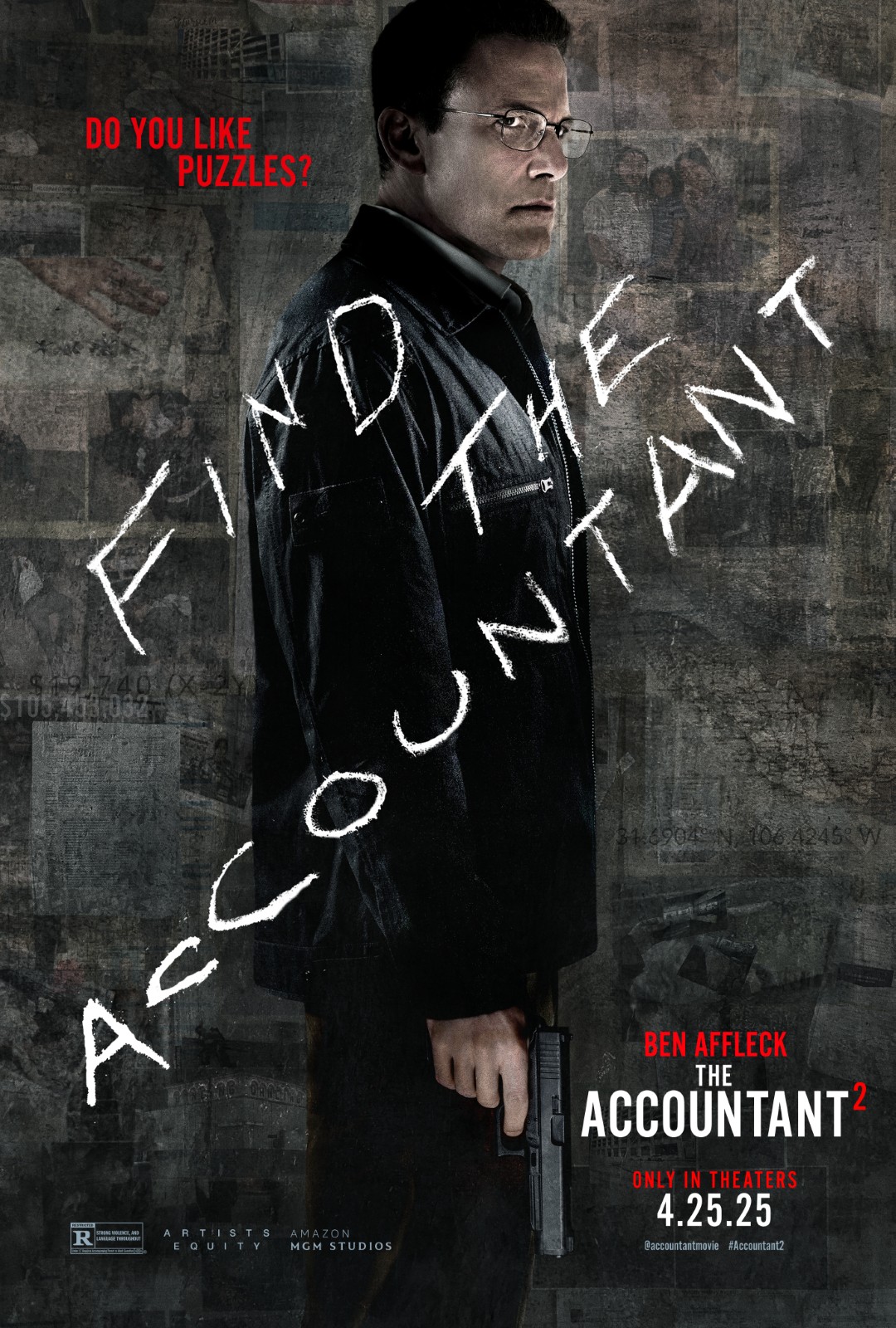

If Alain Guiraudie has still not quite transcended festival obscurity to become an American art-house staple, all the more credit to the films––they’ve never approached niceties, comfortability, or a distillation of bleak perspectives for co-production amenability. But if anything must break through, Misericordia might as well be the one: ten months after its Cannes debut, his existentialist thriller (a little gay, emphatically Catholic) comes to U.S. theaters with Guiraudie participating in a nationwide Q&A tour.

That the dozen years since Stranger by the Lake did little to elevate Guiraudie’s stateside profile––his previous feature, Nobody’s Hero, went effectively unreleased––is no fault of his own. Situated at the Criterion offices last fall, he active an engaged and peripatetic interview subject, returning to points and underlining ideas that characteristically tall language barriers couldn’t fell.

My thanks to Assia Turquier-Zauberman, who provided on-site interpretation.

Alain Guiraudie: Where am I supposed to sit? Freedom. I feel free now.

The Film Stage: Whatever you want to do. It’s just audio.

I’m just talking, okay. So it’s an interview for… for Twitter?

No, it’s for my website.

Ah, okay. I did not understand anything. I thought we were supposed to make a… show set.

I just came here with some questions and a love of your films.

[Laughs] Okay, wonderful.

I saw the movie here last week, in the screening room. Characteristically great. And I was sort of interested that it comes from a novel you’d written a few years ago. Which I thought was interesting because I’ve only read Now the Night Begins, which I really loved.

Okay, yes! Okay.

Your career as a novelist is fascinating to me. You had written Rabalaïre and then adapted it into this film. And you’ve been talking about it since Cannes, in May. Through this, do you feel like you have a special insight into the material of Misericordia because there are these different levels of experience you have with it? Or do you find that when you talk with people about it, you’re still learning new things? Where people are bringing observations of the material you just hadn’t considered.

No. It’s quite, quite surprising and very curious, the way a film functions after it’s been made. I continue to see new things in the film, things that I hadn’t seen in the editing stage until learning a lot, every time, I speak with the audience––every time I speak with film critics, also. Both about the film and about myself.

Do you think people have taken from the film something that you wanted them to take from it? Do you have those kinds of desires and hopes? Or do you wish the films to be a bit more of an open book, without any kind of prescribed reaction or feeling?

[Laughs] The question is a very interesting question. I don’t think I have a message to deliver with the films. I think that I work a lot on emotions and I work a lot on questions that I want to provoke in the spectator. But I always have the feeling, by the time the film is over, that I’ve somehow missed something. And I think that’s because, somehow, by the time I get to the stage where we’re at now, I don’t quite remember both maybe what my intention was from the beginning, but also maybe the evolution of the film throughout its process is such that when you’re writing the script it already moves so much from the original intent, and once it’s incarnated by the actors it changes in this way where the characters are not the actors as once was imagined.

That’s also the luck of the film––that’s also the grace of the film––but it changes some more through the editing process, and so by the time I get there I’m too far from what the original intent had been to have something to deliver that I’m trying to keep a hand on. And also, I’m not sure that what I even had intended was doable or realizable from the start. I think I never manage to do what I intended to do, and I think it’s a very good thing that I don’t. So I don’t know if you know this axiom––I think Robert Bresson is the one who is best to have summarized this filmic journey––he says that a film is killed a first time on-paper, and he uses the word “killed” in this way, and then revived once we see the actors and the set and the costumes in-place; that then the film itself, as material, kills it a second time; and that it is revived again in the editing room. I think that’s a very, very apt summary of the experience.

Photo by Godlis, courtesy of the New York Film Festival.

In your case, maybe you kill it when you turn it into a novel, it’s revived when it’s published, and you kill it again when you write it…

[Laughs] I think I work very, very differently between literature and film, so that even when there are relations between a novel and a film, I don’t think or speak of an adaptation as such. I consider that I really start from scratch, that the characters are fully different––even when they have some kind of lineage to them––and that even what happens between the characters and the film is just wildly, wildly different. So when I write the book, I don’t have to go through this process of killing anything. It’s like a revival straightaway. It’s almost as though writing the book is like being straight to the editing room. [Laughs] Writing a novel has a lot less frustration involved than making a movie.

I think this is getting at something I tapped into with Misericordia right away: this is a really great film of faces.

Ah, okay.

Félix Kysyl is a very strange screen presence––his face I’d describe as being like an adolescent fused with an adult, a weathered babyface. Which plays with that character so well, I think. Meanwhile Jean-Baptiste Durand is hardened and brutish, which feels so how Vincent is written. And obviously there are a lot of considerations that go into who you can cast or when you can cast them, but I do wonder how much the faces of these actors in this film revive, fulfill the characters that you had written.

So as you said: I think it’s really, very different for each actor. In the case of Félix, I was drawn to his ambiguity and the complexity of his face, which comes in contrast with a very, very simple and non-psychological way of acting, and so I was sensitive to the contrast in that. Yes, his face has this quality of being ageless, which gives him the capacity of being possibly an angel, and possibly a demon to the same degree. And I like, then, the way that that interacted with Jean-Baptiste Durand and the priest’s face, who, in my mind, are people who really carry their personality on their face in this way––a kind of “face value,” you would say, so that the priest looks like a priest. Martine also, I think, has a kind of an ambiguity in the way that she looks: there’s something childish in the femininity in her face. She has a candor that was moving for me.

Casting is always a very intimate process, because it’s one that’s based on my desire for the actors––desire that, of course, isn’t sexual per se, but there is a desire for their physique, there is a desire and an attraction to their form. I don’t surround myself with so, so many collaborators, but I do like there to be some people around me in the casting process trying to find some objective reasons to choose an actor or another.

When I saw Misericordia I took a special note of a particular shot of him walking outside as a cloud is passing over the sun––an image that I really loved. And I was kind of startled yesterday because I finally watched Sunshine for the Poor, from 2001…

Okay. Same…

…which has the same image in it. And I’m curious what significance that image might have for you––if that’s something that you were very consciously seeking to achieve both times out. Because if not, it would just be incredible luck.

We have a word in France, a specific word. Maybe if I have a second I’ll find it––there is one in English also––just for the process of this change in luminous intensity and the diaphragm change in the camera. This is something that I like very much; I’m very attached to working with natural light and I love changes in light in this way. I can’t say it’s exactly voluntary in this film––especially because DOPs don’t really like that––but for me, it’s important to work with the reality of light. Though in Sunshine for the Poor, we did wait for this cloud to arrive to start filming.

I don’t think it has… there’s nothing to really disclose about that image for me, other than that there’s something important about restituting the reality of light. It’s interesting that you noticed that because both Sunshine and Misericordia were filmed in basically the same space, the same location, which is a location that’s really striking to me for the beauty of the skies that have a lot of change in clouds, and so it’s something that sort of happens there.

I also watched That Old Dream That Moves, which I know Jean-Luc Godard was quite fond of. If I had made anything and Jean-Luc Godard said it was good I could probably drop dead happy.

[Laughs] Ah, okay.

I wonder what, if anything, that meant for you––especially as a younger filmmaker who hadn’t made so many films up to that point––receiving that kind of notice from Godard?

No, of course it’s nice to hear. I didn’t really know what to do with it at the time. I also have to say, for me, Godard is not the God of cinema that he is for so many of my friends. He’s somebody that I admire very much for his creativity––for everything that he’s invented; for his freedom, of course––but he isn’t sort of my patron saint in this way, so that at the time I would also think, “What would have happened if Lynch had said something like that about my films?” Because that’s sort of closer to who I consider in that way. It would have been very nice also, but I don’t think I have very much to say about that: they are not the people I make movies for, and that’s not where I’m just going to stop and rest. In the meantime, I was thinking that I was a lot more flattered when Bret Easton Ellis said good things about Stranger By the Lake.

Is there a particular person or group that you make movies for?

I’m happy that’s the follow-up, because when I was saying that about Lynch and Godard I was wondering who I make them for. And I realized: maybe not that many people in the end. Maybe I make films with a few people around me in mind, or a few friends of mine. For example: there’s somebody, a close friend, who’s collaborated on several of my films, whose opinion, for a long time, was really the be all, end all of something. If he said the film was bad, that was the end of it; or if he said it was good, that meant… you know. I’m trying, and I think I’m starting to really have succeeded in sort of shrugging the weight of these opinions on me right now, and I would say that that’s some of the freedom I’ve managed to conquer––to be able to kind of follow my own route in this way. And maybe land on what Beckett says, which I think is true: that I’m doomed to fail and to fail better and better and better.

And I do want to say a word about my relationship to the audience, because the audience at large is not an entity that exists for me as I’m making the film. But I do have to admit that by the time the film is done, I am very sensitive to the reception and I’m very sensitive to the way that the room moves when I’m present for a screening. For example: the first screening at Cannes, I think it was very important for me that it be received and felt in the way that I intended it to be felt––that there is a desire for the things to land in a way that I want the audience to laugh, for the things that I was trying to be funny on. I wanted it to be tense in the places where I intended that. So this is maybe a place where I come back to have a certain expectation of what the film is going to do.

And I think that’s the main difference between literature and cinema: in literature there is a certain complicity and a certain relation to the reader, but one that we’re not a witness of, and so to be able to experience with an audience the reception of something that was meant for them to receive is what I keep cinema around for. So I think, actually, I can say that it is for the public that I make the films. [Laughs]

As a fan, I just think you make the films for me.

Ah, okay! No, I should have said… wonderful. Thank you.

Misericordia opens on Friday, March 21; Alain Guiraudie will appear in Boston, New York, Los Angeles, San Francisco, and Chicago for Q&As. Learn more here.

The post Alain Guiraudie on Misericordia, Desiring His Actors, and Praise from Godard and Bret Easton Ellis first appeared on The Film Stage.

![Battle Hordes of Alien Horrors in Survival Shooter ‘Let Them Come: Onslaught’ [Trailer]](https://bloody-disgusting.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/letthemcome.jpg)

![Please Watch Carefully [THE HEART OF THE WORLD]](http://www.jonathanrosenbaum.net/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/the-heart-of-the-world-5-300x166.jpg)

![Passenger Pops Open Champagne Mid-Flight—That Didn’t Go Over Quietly [Roundup]](https://viewfromthewing.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/passenger-pops-champagne.jpg?#)

![[Podcast] Should Brands Get Political? The Risks & Rewards of Taking a Stand with Jeroen Reuven Bours](https://justcreative.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/jeroen-reuven-youtube-1.png)

![[Podcast] Should Brands Get Political? The Risks & Rewards of Taking a Stand with Jeroen Reuven](https://justcreative.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/jeroen-reuven-youtube.png)