Robert De Niro’s The Alto Knights Reveals True Story Behind The Godfather Myth

Producer Irwin Winkler has been trying to get The Alto Knights or a movie similar to it made since the 1970s. It might go back even further he confides while reminiscing of his youth growing up in New York City. At the time, his idea of what a “gangster” looked like was defined by a certain […] The post Robert De Niro’s The Alto Knights Reveals True Story Behind The Godfather Myth appeared first on Den of Geek.

Producer Irwin Winkler has been trying to get The Alto Knights or a movie similar to it made since the 1970s. It might go back even further he confides while reminiscing of his youth growing up in New York City. At the time, his idea of what a “gangster” looked like was defined by a certain image: James Cagney mostly, walking through a downpour of rain while glowering beneath his fedora. Yet that changed when the nightly news started reporting about guys like Frank Costello—the future protagonist of The Alto Knights and the real-life boss of bosses who “retired” from the life around the time words like “Mafia” and “Cosa Nostra” became household terms spoken at the American dinner table.

For Winkler, discovering the existence of Costello in his custom-made suit and media-ready smile was revelatory. For the Mafia, it was deadly. And it took longtime collaborators and colleagues of Winkler’s, guys like Robert De Niro, director Barry Levinson, and the screenwriter of Goodfellas and Casino, Nicholas Pileggi, to open the movie up. They realized The Alto Knights is the story of a war between real-life mob bosses Costello and Vito Genovese (both played by De Niro); it is the story of the men whose conflict inspired The Godfather; and it is the story of why the mob, as those in the life previously understood it, ended forever.

“Barry came up with the idea of it’s a two-hander,” Pileggi says of the central dynamic between De Niro’s two roles as Costello and Genovese. “And it just dawned on me you’re right because afterward it’s over! When Frank Costello perhaps sets up the Appalachia hearing, the Appalachia hearing ends it. It’s over. No more Jimmy Cagney, no more organized crime. It’s over because what comes out of the Appalachia hearing is the McClellan committee, charts and hearings, and Joe Valachi.”

What Pileggi refers to is the turning point that all of The Alto Knights builds toward. Despite being childhood friends, the real-life Frank Costello and Vito Genovese grew apart after the U.S. government (temporarily as it turned out) deported Genovese back to Italy in 1945. In his absence, Costello became the de facto boss of bosses and ran organized crime increasingly like a mid-century corporation until Genovese returned and demanded control of the so-called Luciano Family.

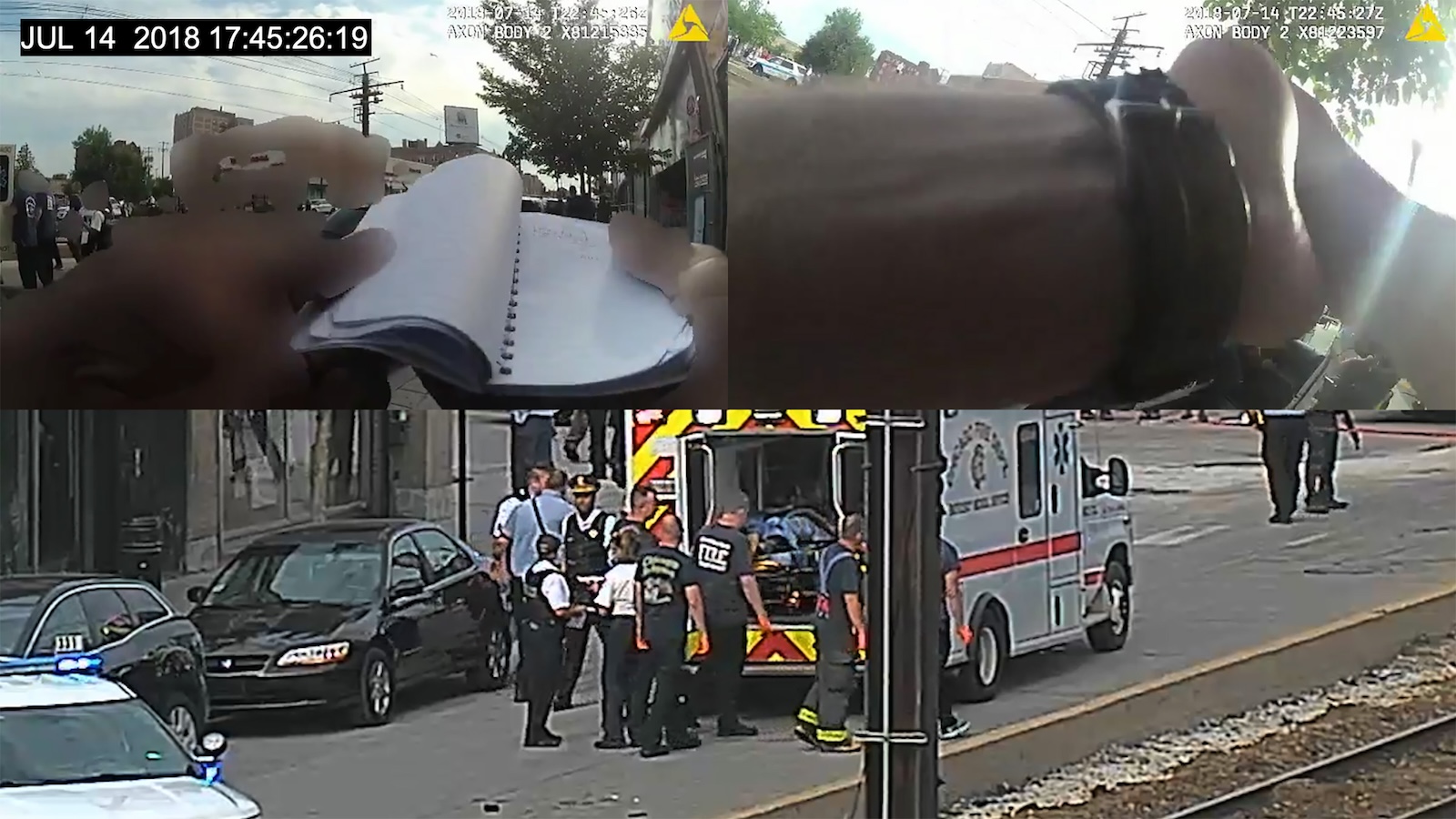

In 1959 he got it after rivals were whacked, and Costello made an unorthodox play for retirement. The Luciano Family became the Genovese Family, and Costello also helped Vito organize a meeting of the mob families in a New York corner of Appalachia where almost everyone (but Costello) wound up arrested. This in turn paved the way for U.S. Senate hearings, Genovese soldier Joseph Valachi uttering the words “Cosa Nostra” on live television, and a certain Italian American author who knew nothing about the Mafia getting a bright idea.

“Joe Valachi gives Mario Puzo everything he needs for The Godfather,” Pileggi laughs today. “That’s the process, and it’s over. The Godfather ends the mystery.”

Yet ironically it is now one of the iconic actors in The Godfather Trilogy, young Vito Corleone performer Robert De Niro, who gets to play Costello and Genovese both when recounting the true events that would inspire Vito’s heir in the first 1972 movie.

“These are two real figures who are well-known mythological characters, underworld characters in New York and in the country,” De Niro says about his dual roles. “So there was a lot of information about them already, and I just went and looked for as much as I could: things where they were filmed and things where they were talking.” The actor even reached out to anyone alive who still might have remembered them from the old days. “Maybe speak to somebody who knew somebody who knew them and told another story about one of these two guys.”

De Niro is circumspect, but his work ethic of profiling the historical figures he portrays is legendary. Even Pileggi marvels at his ability to get wiseguys and other toughs to open up, which is saying something since before earning an Oscar nomination for co-writing Goodfellas, Pileggi was a crime journalist for AP and then New York magazine, which led to him writing Wiseguy, on which Goodfellas is based.

“When on the Casino thing, [De Niro] went down and spent months with Frank ‘Lefty’ Rosenthal,” Pileggi chuckles, “who would not open up to me when I was trying to talk to him. He would say things like, ‘Well I can’t or I don’t know.’ But the minute Bob got in there, Lefty Rosenthal was showing him his closet. He’s showing him his 300 pairs of pastel-colored trousers. I mean, it’s just what happens. He would have made a fabulous reporter.”

He also makes for an interesting double lead in The Alto Knights, which in some eyes might be a gimmick, but from the perspective of collaborators like Winkler—who also produced Goodfellas as well as other De Niro standards like Raging Bull and The Irishman—it was the only natural direction to take.

“When Bob was thinking of playing Costello, he asked me specifically who I thought could play Vito Genovese,” Winkler remembers. “And my instinct was that nobody could play it better than Bob. If he said he wanted to play Genovese, we would then look for another Costello.”

It was certainly a unique proposition, but one that the actor initially admits to having his share of doubts about.

“In the beginning there was a hesitancy because it was unexpected,” De Niro says. “I said, ‘Well, easier said than done. Let’s think about this for a minute.’” After taking a few days to consider the prospect of playing dual roles at this stage in his career, and speaking about it with director and friend Levinson, the star came back and said he was willing to go for it.

“It’s something to try,” De Niro muses. “I’ve not done it before and it also adds to the reason, the justification of my doing another gangster film, even though I’m doing it with everybody I know so well and worked many times with, and I’d probably do it the other way too. But this is even better.”

As it stands, he admits that Costello, the role De Niro originally was attracted to, is perhaps the savvier character. He’s certainly “the diplomat.” But all things being even, Genovese was more delicious for the star: “With the Vito character, he’s a hothead, he’s more fun to play, he’s more explosive, impulsive.”

That explosion gets back to The Godfather of it all.

“Puzo took the whole idea of the Godfather [character] saying to the other members of the mob that he won’t have anything to do with drugs [from Costello],” Winkler contends. “The judges he was responsible for would go along with gambling and they couldn’t care less about prostitution, but when it came to drugs, they drew the line.”

Pileggi agrees, adding, “That battle about the mob being in drugs in reality took place between Frank Costello and Vito Genovese… In The Godfather, you see it depicted between the Marlon Brando character and the rest of the mob.”

Admittedly, there’s a vast tonal difference between the two films, which might be the point. Francis Ford Coppola’s The Godfather is operatic and tragic. The aforementioned Appalachian meeting in The Alto Knights, by comparison, is purely businesslike and even comical as wiseguys skid their nice Italian shoes in mud and cow dung while running from the fuzz.

“I knew Mario when he was working on the novel,” Pileggi says. “Mario is a friend of mine. And he was working on that novel out of the McClellan committee hearings and out of the Valachi tapes. That’s where it all comes from. But I’m basically a reporter rather than a novelist, so what I brought to whatever depiction of that period is, is mostly data and information and facts as a journalist.”

As for an actor involved in both visions, De Niro is coy as to whether he thinks the graceful and honorable Vito Corleone, don of a powerful crime family and defender of the little guy, is pure fiction or not.

“Whether it be then or now, people who have honor have honor and they don’t change,” De Niro considers.

But it’s worth noting that The Alto Knights at least speculates on how classically American this type of business is. Costello even has a line in the movie about how “by the time we got here, the Indians had all been killed, the gold all dug up, and the oil sucked from the ground.” All that was left for immigrants to do to make a fortune was to go into the booming businesses of the early 20th century: corruption.

“The only reason Frank and Vito did anything at all was because the country created Prohibition, which was the key to institutionalizing corruption,” Pileggi notes. “I mean, Prohibition meant there were 45,000 speakeasies in the state of Illinois.” The author points out that the 18th Amendment meant that for nearly a 20-year period, corruption was rewarded. A cop paid $20 to look the other way in 1920 might be a captain on the force or chief inspector by 1932; a lawyer who rented the apartments where the speakeasies were hidden could be on the city council two decades later.

“That’s how they began to control so much of the cities, New York, Chicago, St. Louis, New Orleans,” Pileggi says. Which in some ways was not all terrible for the culture. The speakeasies certainly helped the feminist wave of the 1920s versus the bar halls of the 19th century where no women would be allowed.

“There’s a lot of bad with Cosa Nostra,” Pileggi stresses, “but it had a social element that the mob pictures usually forget… Think of Jimmy Cagney with the gun shooting people and throwing somebody down the stairs, and then go to The Great Gatsby. It’s the same person, but what happened over a 20-year period is he cleaned up his act. He said, ‘Hey, I don’t have to throw that person down the staircase. I can buy a house in Sands Point!’ I think that is what our movie The Alto Knights is trying to say.”

It’s also a guy who still exists today. After all, the real Costello was one of the few mob figures who was never whacked nor died in prison. In fact, he even lived the high life in New York City hotels years after he was supposed to be deported.

“Even after he got out and even after Appalachia, when you are a part of the judicial system, when you are a part of the Department of Justice, and you have subpoenas and you have indictments and you have got them delayed in court—that’s what Costello had to deal with after it was over,” Pileggi says. “He still had 10 years of dealing with court delays, and we see that today in all of the cases that Donald Trump had to deal with, all those delays. They went on for five, six years with Donald Trump, 10 years in some of Donald Trump’s cases. And all of a sudden they’re gone. And that’s what happened with Frank Costello.”

The business changes, people don’t.

The Alto Knights is in theaters now.

The post Robert De Niro’s The Alto Knights Reveals True Story Behind The Godfather Myth appeared first on Den of Geek.

![Bring Riggs and Murtaugh home in a new 4K Blu-ray release of Lethal Weapon [Updated with final artwork]](https://www.joblo.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/lethalweapon-copy.jpg?#)

![‘Ash’: Aaron Paul & Eiza González Talk Flying Lotus’ “Acid Trip” Sci-Fi Film, A Jesse Pinkman Spin-Off, Teasing ‘Fountain of Youth’ & ‘Three-Body Problem’ [The Discourse Podcast]](https://cdn.theplaylist.net/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/18102155/%E2%80%98Ash-Trailer-Eiza-Gonzalez-Aaron-Paul-Star-In-Flying-Lotus-New-Sci-Fi-Film.jpg)

![Delta Passenger Given Vomit-Covered Seat—Then The Flight Attendant Handled It In The Worst Place Possible [Roundup]](https://viewfromthewing.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/a321neogalley.jpg?#)

.jpg?width=1920&height=1920&fit=bounds&quality=80&format=jpg&auto=webp#)

.jpg?width=1920&height=1920&fit=bounds&quality=80&format=jpg&auto=webp#)

.jpg?#)

![Release: Rendering Ranger: R² [Rewind]](https://images-3.gog-statics.com/48a9164e1467b7da3bb4ce148b93c2f92cac99bdaa9f96b00268427e797fc455.jpg)

![[Podcast] Should Brands Get Political? The Risks & Rewards of Taking a Stand with Jeroen Reuven Bours](https://justcreative.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/jeroen-reuven-youtube-1.png)

![[Podcast] Should Brands Get Political? The Risks & Rewards of Taking a Stand with Jeroen Reuven](https://justcreative.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/jeroen-reuven-youtube.png)