In the Hot Seat: On the 4D Experience

“Are You Experienced?” is the spring 2025 edition of the Notebook Insert, a seasonal supplement on moving-image culture.Illustration by Chau Luong.I had tweaked something in my neck a few days before I went to see a 4DX screening of Flight Risk (2025)—a fact I should have considered, but did not. You don’t usually have to think about whether your body is ready for a movie. Ideally, you don’t have to think about your body at all, except maybe as you recline your seat or take a quick trip to the bathroom.Anyway, mine wasn’t ready. Flight Risk is a grimy, cartoonish little thriller in which a US marshal, a mob hitman, and a reluctant witness fight for control of a small airplane as it flies across Alaska. There are moments when 4DX is startlingly effective: when the plane nosedives onscreen and your seat lurches forward as air puffs past your face, and some psychological gap between you and the story suddenly vanishes. It feels, for just a second, as if it is all actually happening. But those moments are remarkable in part because they are so rare. Most of the time, it feels like what it actually is: You are trying to watch a movie, and someone keeps shaking your seat.Not just shaking, of course. 4DX—developed in 2009 by a South Korean theater chain, and now available in hundreds of theaters around the world—seems to incorporate almost every trick from over a half-century of movie gimmicks: a more powerful and variable version of the “Percepto” buzzing seats of William Castle’s The Tingler (1959); the synchronized scents of Smell-O-Vision and AromaRama at the beginning of the 1960s; the surround sound, artificial smoke, and flashing lights of Francis Ford Coppola’s Captain EO (1986), a Disney theme park attraction starring Michael Jackson; the tilting seats and artificial breezes of Disney’s various “Soarin’” rides, the first of which opened in 2001; plus periodic spritzes of water and, apparently, plastic straws that occasionally flail at your ankles, though I haven’t noticed that bit at the screenings I’ve attended. All of them, one begins to realize, are irritants—things you might, in another context, pay extra to avoid: being jostled, poked, blown on, spat at; having the screen obscured by smoke, the theater engulfed by strange smells. Cinema, Walter Benjamin wrote, is an art form that “periodically assail[s] the spectator,” and in that sense, at least, 4DX is the most cinematic experience one can have.Those assaults quickly sort themselves into a hierarchy. Scent is at the bottom, barely present most of the time, and often a bit hard to identify when it is. Smoke is an occasional distraction—once or twice per movie, generally, for a few odd seconds of murk. The puffs of air, which come out of a plastic tube on the headrest to one side of your face, are a little more frequent, and are always a little disconcerting. In the movies I’ve seen, they are most often tied to gunshots—they seem to indicate that every bullet just missed your head, no matter where it was aimed onscreen. The water, sprayed from the back of the seat in front of you, is less frequent but significantly more disconcerting, even repulsive. Robert Pattinson vomits toward the camera in Mickey 17 (2025) and moisture hits you in the face. Mark Wahlberg is punched in the nose in Flight Risk—moisture to the face. Asked by a journalist about a similar “orc blood” effect in retrofitted screenings of The Lord of the Rings: The Fellowship of the Ring (2001), the head of the 4DX production studio said, “I’m sorry.” (Water is the only effect one can manually shut off, using a button on the armrest.)Top: A 4DX armrest. (Photograph by Razgrad.) Bottom: Lobby card for The Tingler (William Castle, 1959).Overshadowing all of these is the seat itself. More than anything else, 4DX is movies that actually move you, in all sorts of ways: the seat can thump at individual parts of your back, tilt in every direction, buzz and rumble and lurch and wobble. Seats have been at the forefront of various efforts by movie theaters over the past few years to lure people off their couches, from the leather recliners that have now become commonplace to “ButtKicker” rumbling seats. 4DX is unusual, though, in its betrayal of the seat’s basic purpose: comfort discarded in the pursuit of novelty.Martin Scorsese’s famous complaint that Marvel movies were more like theme-park rides than cinema has never felt more true than while watching Captain America: Brave New World in 3D 4DX. During the more violent lurchings of the seat you might feel like you really are on a rollercoaster, though without the usual rhythm of anticipation and release (and without the reality of height and speed and wind). The puppet-show effect of post-processed 3D, the weightless, pervasive CGI, and the constant intrusions of the 4DX effects combine to utterly break the narrative illusion. The sense of a window onto another world, of a story unfolding in front of you, is replaced by the sense that you are t

“Are You Experienced?” is the spring 2025 edition of the Notebook Insert, a seasonal supplement on moving-image culture.

Illustration by Chau Luong.

I had tweaked something in my neck a few days before I went to see a 4DX screening of Flight Risk (2025)—a fact I should have considered, but did not. You don’t usually have to think about whether your body is ready for a movie. Ideally, you don’t have to think about your body at all, except maybe as you recline your seat or take a quick trip to the bathroom.

Anyway, mine wasn’t ready. Flight Risk is a grimy, cartoonish little thriller in which a US marshal, a mob hitman, and a reluctant witness fight for control of a small airplane as it flies across Alaska. There are moments when 4DX is startlingly effective: when the plane nosedives onscreen and your seat lurches forward as air puffs past your face, and some psychological gap between you and the story suddenly vanishes. It feels, for just a second, as if it is all actually happening. But those moments are remarkable in part because they are so rare. Most of the time, it feels like what it actually is: You are trying to watch a movie, and someone keeps shaking your seat.

Not just shaking, of course. 4DX—developed in 2009 by a South Korean theater chain, and now available in hundreds of theaters around the world—seems to incorporate almost every trick from over a half-century of movie gimmicks: a more powerful and variable version of the “Percepto” buzzing seats of William Castle’s The Tingler (1959); the synchronized scents of Smell-O-Vision and AromaRama at the beginning of the 1960s; the surround sound, artificial smoke, and flashing lights of Francis Ford Coppola’s Captain EO (1986), a Disney theme park attraction starring Michael Jackson; the tilting seats and artificial breezes of Disney’s various “Soarin’” rides, the first of which opened in 2001; plus periodic spritzes of water and, apparently, plastic straws that occasionally flail at your ankles, though I haven’t noticed that bit at the screenings I’ve attended. All of them, one begins to realize, are irritants—things you might, in another context, pay extra to avoid: being jostled, poked, blown on, spat at; having the screen obscured by smoke, the theater engulfed by strange smells. Cinema, Walter Benjamin wrote, is an art form that “periodically assail[s] the spectator,” and in that sense, at least, 4DX is the most cinematic experience one can have.

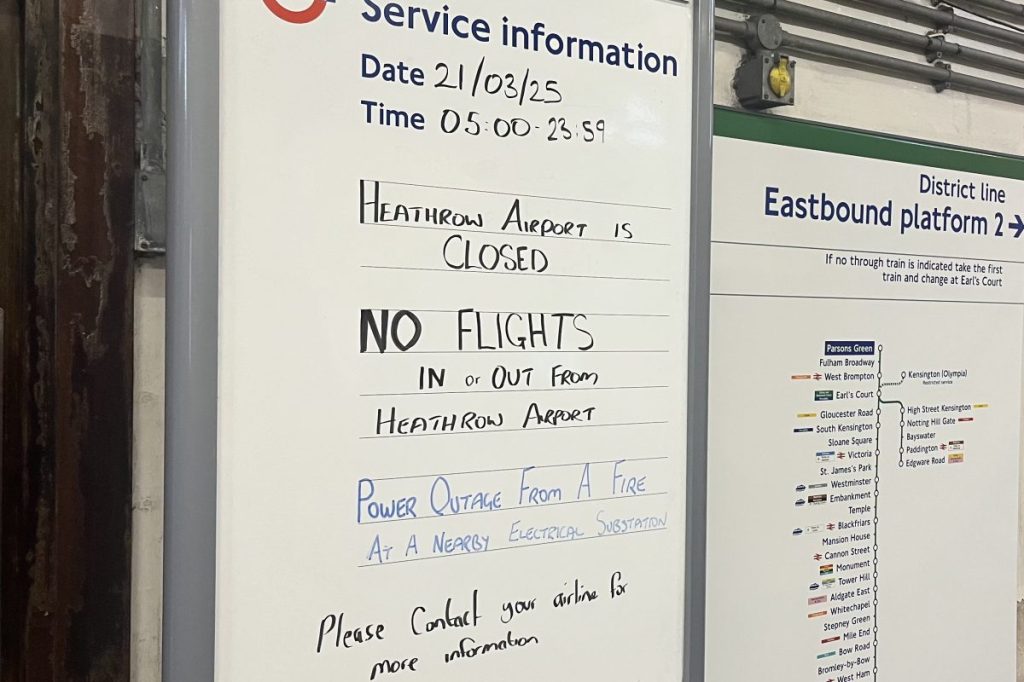

Those assaults quickly sort themselves into a hierarchy. Scent is at the bottom, barely present most of the time, and often a bit hard to identify when it is. Smoke is an occasional distraction—once or twice per movie, generally, for a few odd seconds of murk. The puffs of air, which come out of a plastic tube on the headrest to one side of your face, are a little more frequent, and are always a little disconcerting. In the movies I’ve seen, they are most often tied to gunshots—they seem to indicate that every bullet just missed your head, no matter where it was aimed onscreen. The water, sprayed from the back of the seat in front of you, is less frequent but significantly more disconcerting, even repulsive. Robert Pattinson vomits toward the camera in Mickey 17 (2025) and moisture hits you in the face. Mark Wahlberg is punched in the nose in Flight Risk—moisture to the face. Asked by a journalist about a similar “orc blood” effect in retrofitted screenings of The Lord of the Rings: The Fellowship of the Ring (2001), the head of the 4DX production studio said, “I’m sorry.” (Water is the only effect one can manually shut off, using a button on the armrest.)

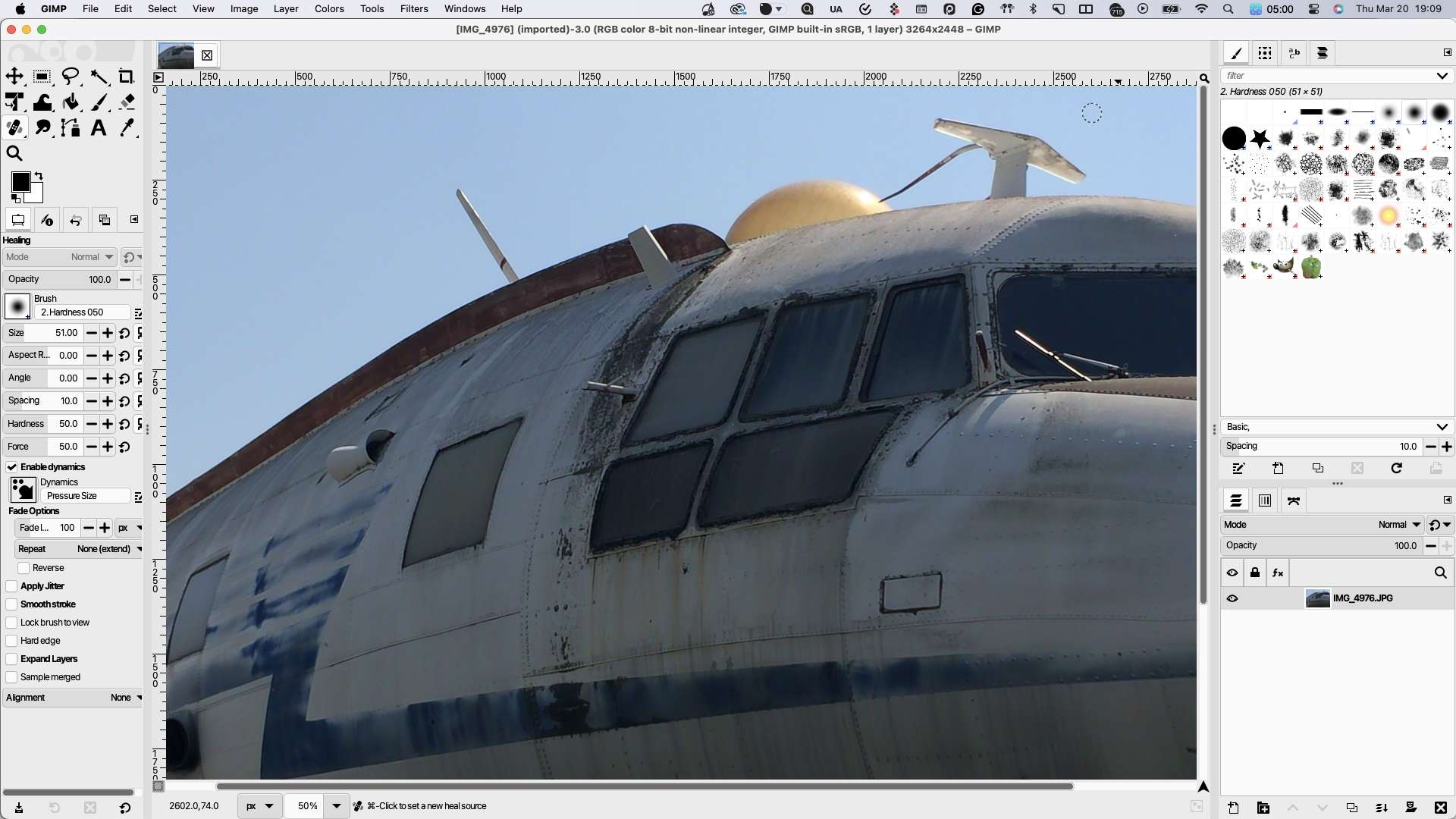

Top: A 4DX armrest. (Photograph by Razgrad.) Bottom: Lobby card for The Tingler (William Castle, 1959).

Overshadowing all of these is the seat itself. More than anything else, 4DX is movies that actually move you, in all sorts of ways: the seat can thump at individual parts of your back, tilt in every direction, buzz and rumble and lurch and wobble. Seats have been at the forefront of various efforts by movie theaters over the past few years to lure people off their couches, from the leather recliners that have now become commonplace to “ButtKicker” rumbling seats. 4DX is unusual, though, in its betrayal of the seat’s basic purpose: comfort discarded in the pursuit of novelty.

Martin Scorsese’s famous complaint that Marvel movies were more like theme-park rides than cinema has never felt more true than while watching Captain America: Brave New World in 3D 4DX. During the more violent lurchings of the seat you might feel like you really are on a rollercoaster, though without the usual rhythm of anticipation and release (and without the reality of height and speed and wind). The puppet-show effect of post-processed 3D, the weightless, pervasive CGI, and the constant intrusions of the 4DX effects combine to utterly break the narrative illusion. The sense of a window onto another world, of a story unfolding in front of you, is replaced by the sense that you are trapped in a vast, intricate machine, eating popcorn as it flails around you.

Yet, at the center of it all, the movie remains. That’s the biggest problem with 4DX, really. The techniques of theme-park entertainment, of extra-cinematic “immersion,” are fundamentally at odds with cinematic storytelling: with cuts, with changes of perspective, with most of the ways in which things tend to happen to people onscreen. There’s a reason theme-park rides that use filmed footage, like the various iterations of Soarin’, maintain a single, mostly continuous point of view. It’s the same reason VR productions use edits sparingly, if at all, and video games, even at their most “cinematic,” either wall off their film-like segments in non-interactive cutscenes or stick very closely to the main character’s point of view. It’s a bit obvious to say, but almost all movies, and late-stage Marvel movies in particular, flit rapidly between different vantages, locations, and scales. That makes a 4DX film strangely hard to keep up with, or perhaps it’s that 4DX can’t keep up with the film. Our minds can move at movie speed, but not our bodies.

It is often unclear whose sensations, exactly, the 4DX experience is meant to be simulating; the effects seem to relate to several different characters, and sometimes to the camera itself, in rapid succession. The experiential incoherence is most obvious during fight scenes: Captain America is stabbed in the shoulder and the chair pokes you there; he throws his opponent into a wall and the chair jostles you; someone shoots a gun and air puffs past your cheek. It is as disorienting in the intimate, sadistic hand-to-hand violence of something like Flight Risk as it is in the bloodless, bombastic slugfests of Marvel films. Both result in a kind of physical cacophony, genuinely unpleasant to a degree rarely achieved by mainstream entertainment. Perhaps the only way to fully avoid these problems would be to remain locked into a single point of view, one gimmick coming to the rescue of another. The ideal 4DX movie might just be Ilya Naishuller’s first-person action flick Hardcore Henry (2015)—or RaMell Ross’s subjective-camera drama Nickel Boys (2024), for that matter, though the thought of watching the film’s depictions of reform-school abuse with vibrating seats and synchronized mist feels more than a little blasphemous.

Top: Twisters (Lee Isaac Chung, 2024). Bottom: US military personnel training on a Link Aviation flight simulator, San Antonio, Texas (1953). (Photograph courtesy of the DeGolyer Library, Southern Methodist University.)

These issues recede temporarily when the films turn their attention to larger, more encompassing phenomena, for which every point of view is more or less the same: big explosions are far more satisfying than gunfights. Weather in general works well; Twisters (2024) is the most successful 4DX release to date. For many movies, the opening 4DX bumper, in which the screen fills with waves and the seats rise and fall to match, is more effective than anything that follows. (In under-attended screenings, the rows of empty seats vigorously undulating for no one is a strangely delightful spectacle.) The moving-seat technology was first developed for flight simulators beginning in the 1920s, and depictions of flying are especially pleasing. The plane on the screen banks and your seat tilts with it; a superhero hurtles toward the ground with the camera close behind as your seat pitches forward. This is when 4DX works.

Yet even then, there’s usually something a little off. The range and violence of the chair’s movements are impressive, their effect a little less so. The timing is often slightly out of sync with the action on the screen. There’s a scene in Captain America: Brave New World—repeated in every trailer—when the Captain lands in the middle of a group of bad guys, tells them to “wait for it,” then watches the shockwave from his impact knock them all over. Both times I’ve seen it, the rumble in my seat arrived just a little later than the impact onscreen. It’s another way in which 4DX separates your tactile sensations from those of your eyes and ears, and pits them against each other.There are also plenty of times when it isn’t quite clear what the sensations induced by 4DX are meant to represent. Your seat rumbles and pulses: Is that… a heartbeat? The footsteps of some approaching giant? Or is it just reinforcement for the pounding of the soundtrack? In many ways, this feels like the early years of video-game haptics, the era of the Nintendo Rumble Pak (1997) and its various successors and imitators, tiny motors attached to or embedded within video game controllers that couldn’t do much more than buzz or not buzz, leaving you to more or less guess what they were signaling.

That comparison could be a reason for optimism about the future of 4DX. Haptic feedback has now become a standard feature on most video game controllers, with enormous improvements in the subtlety and variety of the sensations they can offer. The controllers for the PlayStation 5 can communicate the gentle pattering of rainfall, and the difference between your character walking on grass and on ice; the variable resistance of its trigger buttons can get across the gradually increasing tension of pulling back a bowstring, or the sharp snap of flipping a switch. One can imagine a 4DX chair with similar capabilities, able to conjure a finger tapping at your shoulder, or plants brushing along the backs of your legs—though how appealing that might be is another question entirely.

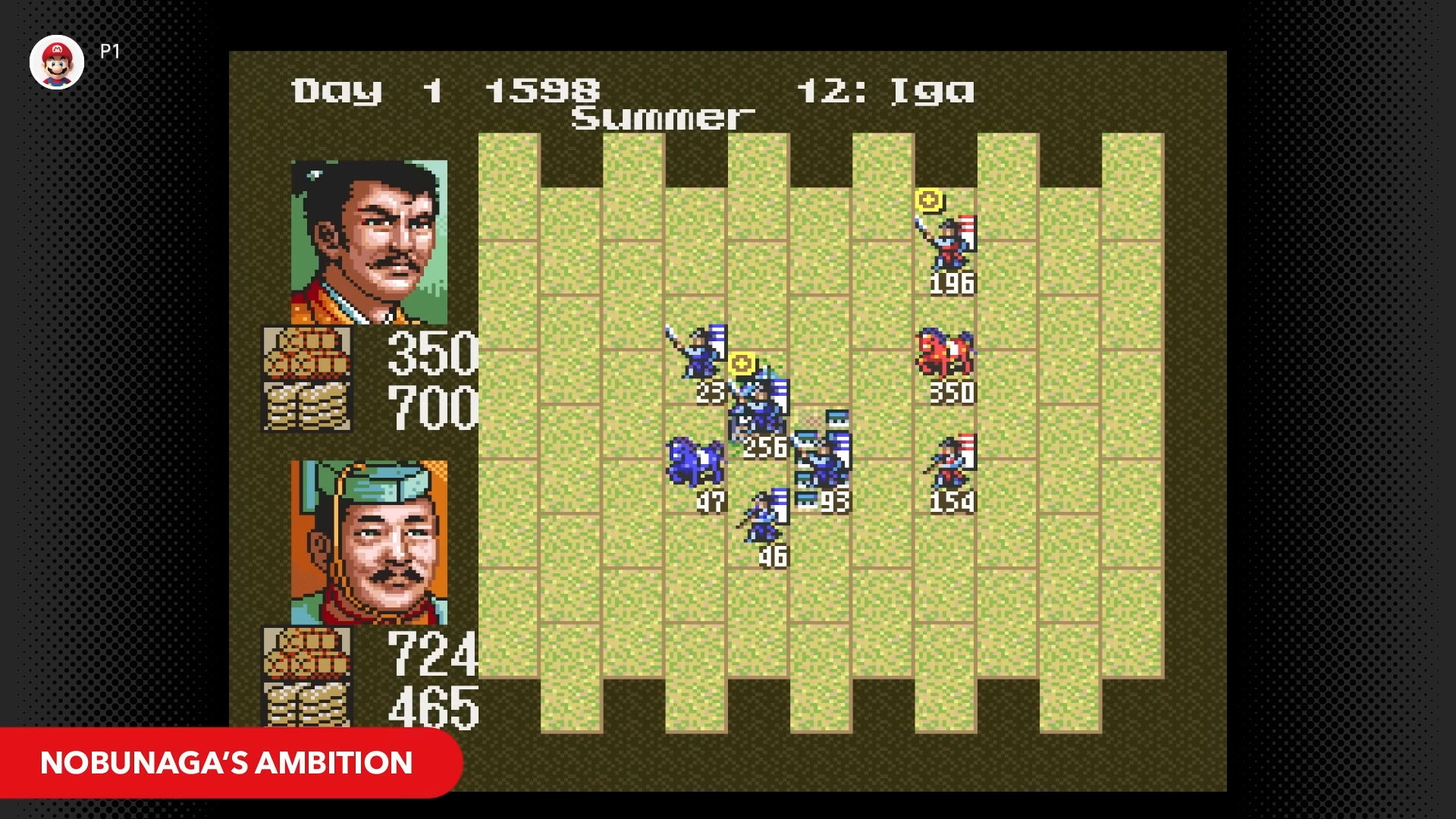

In another sense, the history of video game haptics is a demonstration of the limits of this kind of technology. Haptic feedback has become commonplace, but it has also changed almost nothing. Despite recent technological refinements, most games use it in a rote and limited fashion: a few rumbles here and there when you’re being damaged, or firing a gun, or driving off-road, and otherwise not much. Only a few games, most made by Sony itself—Returnal (2021), Astro Bot (2024)—make full use of the PS5 controller’s capabilities. Haptics seem most effective not in stirring emotion but in communicating much more practical information: not the controller in your hands making a gunfight feel more intense, but the iPhone telling you that you’ve unlocked it, or taken a photo.

Rez (Tetsuya Mizuguchi, 2001).

Then, underlying all of it, there is the question of those hands. 4DX has little access to the front of your body beyond the occasional spritzing, and none at all to your hands. “The most accurate part of our touch perception comes from the hands,” the philosopher Mark Paterson noted in his The Senses of Touch (2007), which is why René Descartes and many subsequent philosophers imagined people who relied on touch as “seeing with the hands.” Outside the movie theater, almost all haptics are aimed primarily, or entirely, at the hands. The field of teledildonics is one obvious exception, along with a few extremely niche video-game peripherals like the Trance Vibrator, meant to add full-body vibrations to the mind-bending 2001 PS2 shooter Rez, in which all the action syncs up with a techno soundtrack. I doubt any major studios would be interested in pursuing remote-controlled sex toys, though the latter suggests an interesting route: perhaps 4DX would be better suited to psychedelic light shows than blockbuster movies.

Paterson also emphasizes that haptics have generally been used to allow “a more active exploration” of whatever is being represented, which points to one of the less obvious ways that 4DX undermines itself. Watching passively comes naturally to us, but to be able to feel without being able to do anything, even move away from the feeling, is strange and subtly frustrating, especially when that captive passivity lasts for several hours. Interaction is one of the few movie gimmicks not incorporated into 4DX. The very first interactive film, Radúz Činčera’s One Man and His House (1967), asked the audience to vote after every reel on what the main character should do, their decision determining which reel would be played next. That would only add to 4DX’s already formidable array of distractions (though, at some point, what’s one more?), and the subsequent half-decade of attempts at interactive filmmaking does not inspire confidence. But it might, at least, make 4DX films less of a trial to sit through.

That, of course, would require that films actually be made with 4DX in mind. So far, the effects are only added after the fact, with only limited involvement, if any, from the filmmakers. (And it is sometimes, as with the Lord of the Rings trilogy, added years after the fact, in a kind of multi-sensory form of colorization.) However the format develops—if it develops—it is hard to imagine it ever being worthwhile without more direct involvement by filmmakers. The gulf between those movies conceived for and shot in 3D (Avatar, 2009; Pina, 2011; Cave of Forgotten Dreams, 2010) and the many more that simply have 3D added in post-production is immense. The early days of surround sound benefited from the intense engagement of filmmakers like Francis Ford Coppola—Apocalypse Now (1979) was, at his insistence, one of the first films released with a Dolby six-channel sound mix—not to mention sound, color, widescreen stocks, and other innovations that have long since transcended gimmickry.

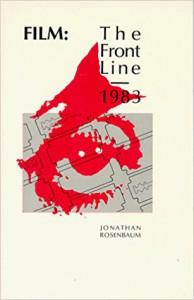

Sensorama patent illustration and advertisement (Morton Heilig, 1962).

Morton Heilig’s “Sensorama”—a 1962 device that used a moving seat, stereoscopic display, fans, speakers, and an odor emitter to simulate a helicopter ride, a motorcycle trip through the streets of New York City, and other experiences—is mostly remembered these days as an early form of virtual reality. But it could just as easily be seen as a one-person 4DX screening room, showing a film shot for the purpose. He never found sufficient funding, and it’s been a long time since anyone has been able to try Sensorama, but the account Howard Rheingold gives in Virtual Reality (1991) of his own experience with Heilig’s machine is tantalizing: “The motorcycle driver was reckless,” he reports, “which made me mildly uncomfortable, much to my delight.”

In 1955, as he was beginning to work on the device, Heilig published an essay called “The Cinema of the Future” in which he imagined films that fill the entire visual field, and can address all five senses at once. He also predicted the excesses and aggravations of cinematic novelties like 4DX: “filmmakers once in possession of a new power,” he writes, “usually cling to it like a drowning man to a life raft,” piling on the effects “just to ‘make sure the point gets across.’” I thought back to his call for subtlety as I winced my way through Flight Risk—and to how he opened the essay, surveying the desperate cinematic innovations of the 1950s: “Pandemonium reigns supreme in the film industry.”

Keep reading “Are You Experienced?”

![‘Eyes Without a Face’ Is a Horrific Quest for Identity [The Lady Killers Podcast]](https://bloody-disgusting.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/Screenshot-2025-03-21-at-7.25.25-AM.png)

![Parkour Mascot Horror Title ‘Finding Frankie’ Arrives April 15 on Console [Trailer]](https://bloody-disgusting.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/findingfrankie.jpg)

![‘Andor’: Tony Gilroy Teases More Romance, Season 2 Guests, Additional ‘Rogue One’ Characters & More [Interview]](https://cdn.theplaylist.net/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/20133148/tony-gilroy-andor-season-2.jpg)

![Elizabeth Olsen Says She’s Pitched A “Gnarly” White-Haired Wanda Returning To Marvel 50 Years Later [Exclusive]](https://cdn.theplaylist.net/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/20121325/Elisabeth-Olsen-WandaVision-Wanda-Scarlet-Witch.jpg)

![Delta Passenger Given Vomit-Covered Seat—Then The Flight Attendant Handled It In The Worst Place Possible [Roundup]](https://viewfromthewing.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/a321neogalley.jpg?#)

.jpg?width=1920&height=1920&fit=bounds&quality=80&format=jpg&auto=webp#)

![Release: Rendering Ranger: R² [Rewind]](https://images-3.gog-statics.com/48a9164e1467b7da3bb4ce148b93c2f92cac99bdaa9f96b00268427e797fc455.jpg)

![[Podcast] Should Brands Get Political? The Risks & Rewards of Taking a Stand with Jeroen Reuven Bours](https://justcreative.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/jeroen-reuven-youtube-1.png)

![[Podcast] Should Brands Get Political? The Risks & Rewards of Taking a Stand with Jeroen Reuven](https://justcreative.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/jeroen-reuven-youtube.png)