Bong Joon-ho in Hollywood, and Outer Space

Illustrations by Manshen Lo.In the opening sequence of Bong Joon-ho’s Mickey 17 (2025), we meet our protagonist, Mickey Barnes, on the verge of his seventeenth death, anxiously awaiting a pack of putatively flesh-eating “creepers” at the bottom of a crevasse. His friend Timo, who rappels down only to retrieve Mickey’s expensive gear, treats Mickey’s impending death as nothing more than a laughable workplace incident. Mickey’s backstory is then revealed in a series of flashbacks, explaining the unique conditions of his immortality: how financial turmoil on Earth drove him to volunteer as an infinitely reproducible “expendable” for an outer-space expedition, meaning he’s been subjected to brutal human experiments that often culminate in his death and unceremonious rebirth via 3D printer.Timo’s nonchalant attitude, just one aspect of the cruelty Mickey has to endure, is typical of Bong’s penchant for shifting tonal registers to render comedy poignant and tragedy farcical.“What does it feel like to die?” is the question that everyone keeps asking Mickey, whether out of honest curiosity or cruel sarcasm. But his deaths register as banal; they’re not major emotional beats. His immortality, which enables a life of perpetual servitude and exploitation, amounts only to the latest technological breakthrough and a metaphysical wonder for lucky mortals.Elsewhere in Bong’s filmography, existential questions about death point to an entanglement between politics and film form. At the outset of The Host (2006), an amphibian creature kidnaps a middle-school girl, Park Hyun-seo, from a waterfront park in broad daylight. Upon realizing that the girl’s disappearance is a mere inconvenience to the government, which hopes to obliterate the monster while keeping the media coverage contained, her devastated family takes it upon themselves to bring her home safe. Hyun-seo’s fate was the subject of a lively critical discourse when the film was released. For many critics, the Park family’s ultimate failure to save her life exemplifies the film’s subversion of monster-movie tropes. In his essay “The Monstrous, the Politics of Piksari,” Jung Sung-il, one of South Korea’s most influential critics, challenges this assessment.1 Observing how every scene showing the girl in the creature’s lair is either preceded or followed by a shot of her father Kang-du falling asleep, Jung instead posits that Hyun-seo dies at the beginning of the film and is alive only in Kang-du’s wishful thinking.This interpretation changes the meaning of the central struggle in the film. It is not that the Park family fails to save her despite their prodigious efforts; rather, they choose to embark on the rescue mission even though Hyun-seo is probably dead. In defiance of the state’s indifference to civilian lives, her dysfunctional family bands together to affirm the dignity of her life—not unlike how Antigone risks her life to retrieve her brother Polynices’s body. Hyun-seo needs to stay “alive” in her father’s imagination in order for The Host to fulfill the rescue narrative template required of the monster movie. Hyun-seo is a working-class girl who lives inside her father’s container-box cafeteria in the waterfront park by the Han River. Each day after school, she has to return to the park where the monster has been sighted. It would take extraordinary good fortune for her to avoid the creature, whereas it is sheer bad luck when visitors to the park are attacked. Her class status makes her especially vulnerable to disaster and, in the eyes of the state, unworthy of protection. The film was inspired by a 2000 toxic-waste scandal, the McFarland Incident, in which civilian contractors employed by the US military stationed in Seoul dumped 24 gallons of a corpse preservative including formaldehyde into the Han River, the city’s main source of drinking water. When details of this disposal came to light, environmental justice organizations, not the Korean government, were the ones to seek justice and condemn the American military, which blocked the apprehension of the perpetrators until the escalating public outrage made it untenable.2 To blame the creature for Hyun-seo’s unfortunate fate is to ignore the social structure that has determined it. Hyun-seo’s death is not a personal tragedy but a consequence of state failures. The Host (Bong Joon-ho, 2006).In a 2006 interview with Cahiers du cinéma, Bong uses the Korean word piksari (삑사리) to characterize a moment from The Host when Kang-du’s brother Nam-il braces himself to kill the monster with his last Molotov cocktail, only to accidentally drop it on the ground.3 Originally a slang word referring to choking under pressure while playing pool, the term now applies more broadly to ridiculous mistakes. Many of Bong’s characters slip up in dramatically crucial moments, often to comical, slapstick effect: In Parasite (2019), a cop blows his cover when he trips on a staircase; in Barking Dogs Never Bite (2000), an eccentri

Illustrations by Manshen Lo.

In the opening sequence of Bong Joon-ho’s Mickey 17 (2025), we meet our protagonist, Mickey Barnes, on the verge of his seventeenth death, anxiously awaiting a pack of putatively flesh-eating “creepers” at the bottom of a crevasse. His friend Timo, who rappels down only to retrieve Mickey’s expensive gear, treats Mickey’s impending death as nothing more than a laughable workplace incident. Mickey’s backstory is then revealed in a series of flashbacks, explaining the unique conditions of his immortality: how financial turmoil on Earth drove him to volunteer as an infinitely reproducible “expendable” for an outer-space expedition, meaning he’s been subjected to brutal human experiments that often culminate in his death and unceremonious rebirth via 3D printer.

Timo’s nonchalant attitude, just one aspect of the cruelty Mickey has to endure, is typical of Bong’s penchant for shifting tonal registers to render comedy poignant and tragedy farcical.“What does it feel like to die?” is the question that everyone keeps asking Mickey, whether out of honest curiosity or cruel sarcasm. But his deaths register as banal; they’re not major emotional beats. His immortality, which enables a life of perpetual servitude and exploitation, amounts only to the latest technological breakthrough and a metaphysical wonder for lucky mortals.

Elsewhere in Bong’s filmography, existential questions about death point to an entanglement between politics and film form. At the outset of The Host (2006), an amphibian creature kidnaps a middle-school girl, Park Hyun-seo, from a waterfront park in broad daylight. Upon realizing that the girl’s disappearance is a mere inconvenience to the government, which hopes to obliterate the monster while keeping the media coverage contained, her devastated family takes it upon themselves to bring her home safe. Hyun-seo’s fate was the subject of a lively critical discourse when the film was released. For many critics, the Park family’s ultimate failure to save her life exemplifies the film’s subversion of monster-movie tropes. In his essay “The Monstrous, the Politics of Piksari,” Jung Sung-il, one of South Korea’s most influential critics, challenges this assessment.1 Observing how every scene showing the girl in the creature’s lair is either preceded or followed by a shot of her father Kang-du falling asleep, Jung instead posits that Hyun-seo dies at the beginning of the film and is alive only in Kang-du’s wishful thinking.

This interpretation changes the meaning of the central struggle in the film. It is not that the Park family fails to save her despite their prodigious efforts; rather, they choose to embark on the rescue mission even though Hyun-seo is probably dead. In defiance of the state’s indifference to civilian lives, her dysfunctional family bands together to affirm the dignity of her life—not unlike how Antigone risks her life to retrieve her brother Polynices’s body. Hyun-seo needs to stay “alive” in her father’s imagination in order for The Host to fulfill the rescue narrative template required of the monster movie.

Hyun-seo is a working-class girl who lives inside her father’s container-box cafeteria in the waterfront park by the Han River. Each day after school, she has to return to the park where the monster has been sighted. It would take extraordinary good fortune for her to avoid the creature, whereas it is sheer bad luck when visitors to the park are attacked. Her class status makes her especially vulnerable to disaster and, in the eyes of the state, unworthy of protection. The film was inspired by a 2000 toxic-waste scandal, the McFarland Incident, in which civilian contractors employed by the US military stationed in Seoul dumped 24 gallons of a corpse preservative including formaldehyde into the Han River, the city’s main source of drinking water. When details of this disposal came to light, environmental justice organizations, not the Korean government, were the ones to seek justice and condemn the American military, which blocked the apprehension of the perpetrators until the escalating public outrage made it untenable.2 To blame the creature for Hyun-seo’s unfortunate fate is to ignore the social structure that has determined it. Hyun-seo’s death is not a personal tragedy but a consequence of state failures.

The Host (Bong Joon-ho, 2006).

In a 2006 interview with Cahiers du cinéma, Bong uses the Korean word piksari (삑사리) to characterize a moment from The Host when Kang-du’s brother Nam-il braces himself to kill the monster with his last Molotov cocktail, only to accidentally drop it on the ground.3 Originally a slang word referring to choking under pressure while playing pool, the term now applies more broadly to ridiculous mistakes. Many of Bong’s characters slip up in dramatically crucial moments, often to comical, slapstick effect: In Parasite (2019), a cop blows his cover when he trips on a staircase; in Barking Dogs Never Bite (2000), an eccentric bookkeeper runs into a door during a chase. Piksari also gives us a way of understanding how Bong’s formal strategies embrace “failures,” the most powerful example of which is found in Memories of Murder (2003). Midway through the film, detective Park Doo-man—his name clearly a pun on that of former fascist president Chun Doo-hwan—rushes to a paddy field after hearing of the latest killing. Here, Bong opts for a continuous tracking shot closely following Park, approximating the opening of Orson Welles’s A Touch of Evil (1958), one of Bong’s all-time favorites. The Cadillac and the ticking bomb of the earlier film are replaced with an old tractor that soon runs over—and erases—a footprint left on a narrow pathway that might have led Park to catch the serial killer. This particular moment of piksari operates on three different levels: the imperfect simulation of a Hollywood aesthetic; the failure to trace the evidence, and thus to adhere to a “Western” model of forensic science; and finally, the allegorical incompetence of an authoritarian regime. Here, piksari becomes a type of formalism that sardonically reflects on the political architecture of South Korea and US imperialism; we might see the same sort of “failure” in The Host’s deviations from genre templates.

If Bong’s English-language films tend to feel flat, their critical edges dulled, it is because piksari operates in them as a purely slapstick device. In his first foray into international coproduction, Snowpiercer (2013), revolutionary leader Curtis slips on a gutted fish on the floor during a bloody confrontation with axe-wielding guards. Curtis’s fall cues the imminent failure of his political vision, rhyming with so many failed revolutionary uprisings, but the moment rings hollow due to the lack of accompanying formal “imperfection.” In Mickey 17, Bong tries to refresh his style, rendered stale in English, with in-your-face satire. Instead of functioning as a punctuation mark to disrupt the story and defy formal expectations, piksari gives the film its exaggerated tonal register: The film is suffused with caricatures of real-world political villains and ample physical comedy. But instead of cohering into a colorful tapestry that weaves satirical precision with irreverent attitudes toward genre templates, it frequently feels like a series of Saturday Night Live–style sketches barely stitched together by a thin plot—the marriage of form and politics that is integral to piksari is lost in translation.

Memories of Murder (Bong Joon-ho, 2003).

Piksari’s “translation” problem cannot be fully understood without delving into Bong’s relation to the history of Korean cinema, specifically the Korean Artist Proletariat Federation (KAPF), a Marxist-Leninist artist collective active from 1925 to 1935, when Korea was under Japanese colonial rule. In 1941, Im Hwa, one of the KAPF’s theoretical architects, wrote a pivotal essay, “Discourse on Joseon Cinema,” that considered technical defects prevalent in Korean cinema at the time.4 Ahn Jong-hwa’s Turning Point of the Youngsters (1934), the oldest surviving Korean film, is emblematic of his observations. Featuring countless out-of-focus shots and awkward camera movements, it seems unsure if it wants to be heightened melodrama, shōshimin-eiga (petty bourgeois film), or a youth film. For Im, such incoherent formalism was at once an obstacle to be overcome and a condition of possibility for a locally specific film language that could challenge the hegemonic cinemas of Imperial Japan and the United States. Along with Western music, theater, and novels, cinema was introduced to the peninsula during the Japanese occupation. Film was still in its infancy and relied heavily on borrowing from the established arts, like literary fiction, stage acting, and music. Im saw a parallel between this influx of external influences and the hybrid identity of Korea, which was undergoing radical social transformations through its encounter with capitalist modernity as filtered through the Japanese Empire. He was especially fascinated by the strong influence of American and Japanese genre films on Korean filmmakers and how the country’s dire economic reality prohibited them from successfully mimicking the production value of these films. Embracing hybridity, Im argued, would result in a homegrown Marxist filmmaking tradition that captures the contradictions of capitalism and imperialism, without succumbing to nationalistic nostalgia for precolonial times.5

The critic Yoo Un-seong argues that piksari is a formal expression of Korea’s postcolonial hybridity.6 For Yoo, Bong’s aesthetic trademarks are not just auteurist quirks but a belated answer to Im’s prophetic vision from 1941. His jarring tonal shifts and unpredictable genre-bending reflect these tensions in Korean history; the peninsula’s tragic experiences under both Japanese and American imperialism are layered on top of each other like a palimpsest. When Bong draws inspiration from the films of Shohei Imamura and Welles, for instance, he does not simply “import” these foreign influences and put a local spin on them, but recontextualizes them entirely. Much like the way Touch of Evil resurfaces in Memories of Murder, Bong’s artistic vision arises from the mutations of these reference points in the specific geopolitical circumstances of South Korea. Just as the deformed creature in The Host is a chimera of fish and frog, and of Hollywood and kaiju traditions, Bong’s filmmaking sensibility stands at the convergence of the past and present imperial powers that define modern Korea.

Goryeojang (Kim Ki-young, 1963).

In elucidating piksari’s geopolitical underpinning, Yoo draws a comparison between Bong and Kim Ki-young, whom Bong often cites as a formidable influence. In South Korea, name-dropping Kim has been a shorthand for situating Bong in the history of Korean cinema, but Yoo provides substantial analysis. He maintains that what we often identify as Kim’s style is in fact synonymous with the “malocclusion of sociopolitical, economic, and cultural conditions that have warped and twisted the national cinema.”7 The Housemaid and Parasite are bound together less by narrative resemblances or shared visual metaphors than by how the two filmmakers formally metabolize this disjuncture.

Recent scholarship on Kim’s filmography supports Yoo’s critical insight. In the course of analyzing Parasite’s superficial similarities to The Housemaid, film historian Geum Dong-hyun goes so far as to argue that the popular imagination of Kim has become a caricature derived from what we deem to be his influence on Bong’s films.8 While The Housemaid grapples with class struggle to a certain extent, it primarily explores repressed sexuality in a bourgeois milieu. This fascination manifests itself in more abrasive ways in two of Kim’s undersung masterpieces, Ban Geum-ryeon (1981) and Iodo (1977), both of which were censored by the military junta for their perceived sexual obscenity. The latter is set on an island exclusively populated by women, who go hysterical over an unexpected male visitor and do whatever it takes—including necrophilia as part of a shamanic ritual in order to reproduce. We could infer class politics in Iodo, but the struggle of the working class is not central to Kim’s vision. Geum’s interview with Kang Chul-woong and Song Myung-geun, Kim’s former assistant directors who went on to have directorial careers in softcore pornography, reveals that Kim especially lamented the Korean government’s strict censorship of sexual content; in 1994, after Korea’s democratization, Kim undertook a stage production of Henrik Ibsen’s Ghosts, whose daring exploration of sexual transgressions had scandalized Europe upon its publication in 1881. Kim’s preoccupation with carnal desire, not class politics, should be at the forefront of any critical assessment of his filmography.

Although seldom mentioned by Bong, Kim’s Goryeojang (1963) is more illustrative of the two filmmakers’ affinities than The Housemaid. The film’s premise is reminiscent of Keisuke Kinoshita’s Ballad of Narayama (1958) and Imamura’s The Ballad of Narayama (1983), about a mythical tradition of abandoning elderly parents to die on the side of a mountain. Set in a rural village in feudal Korea, Kim’s interpretation of this legendary custom aggressively melds disparate genres, atmospheres, and critical modes together, combining elements of anthropology, lustful melodrama, hard-boiled action, and occultism. “Goryeojang is truly a ‘monstrous’ film for bringing all these elements together even at the risk of a rupture in its formal integrity,” writes Yoo.9 Kim, who lived through the colonial period, the Korean War, and subsequent military dictatorships in the South, replicated the incoherent identity of his country in his twisted formalism—much like Bong has. Both are cinematic heirs to KAPF’s theoretical legacy, but they took different paths to get there. Kim articulates Korea’s hybridity through libidinal economy, and Bong through political economy.

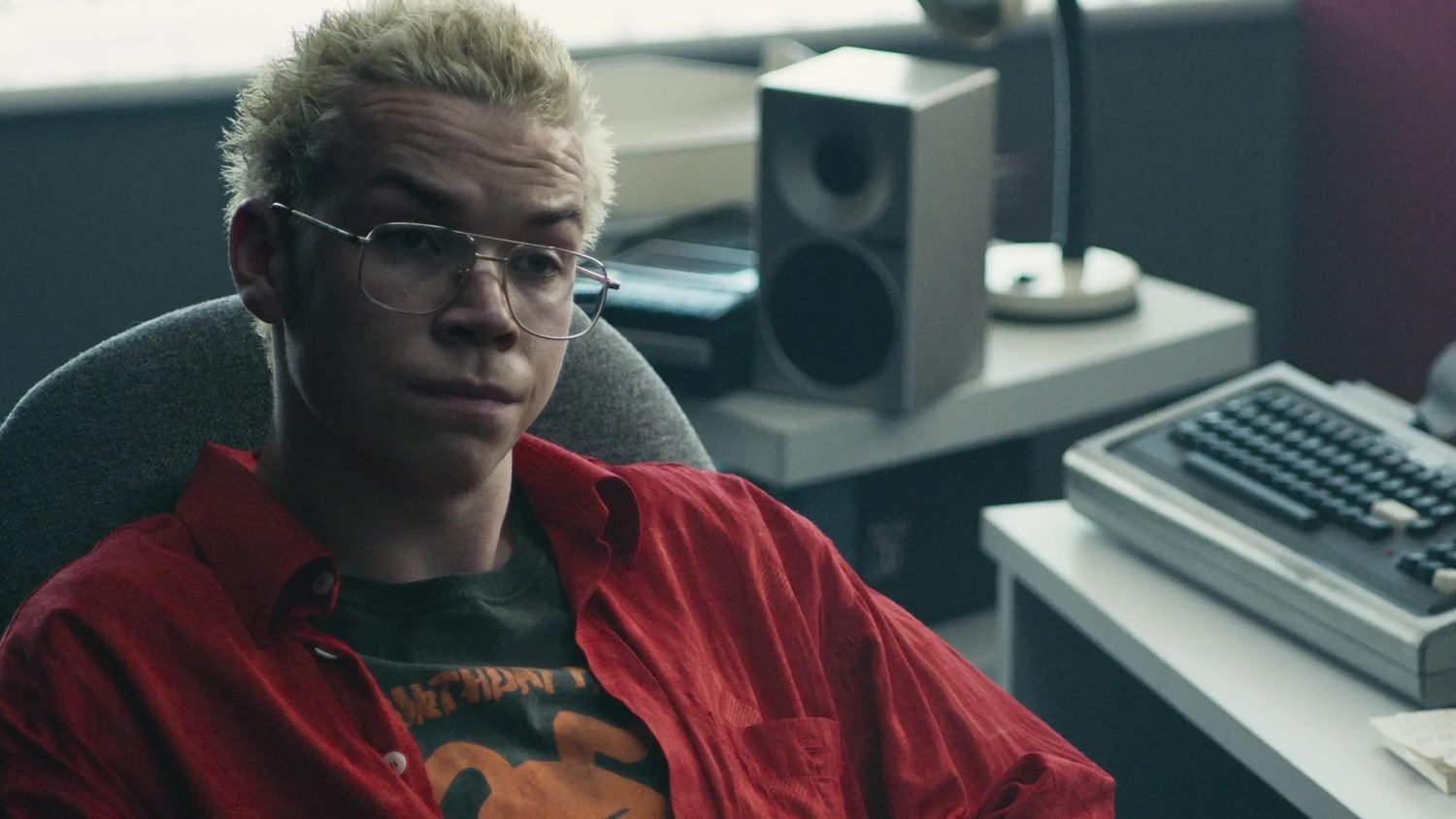

Mickey 17 (Bong Joon-ho, 2025).

Whether or not Bong’s style can be translated into the context of Hollywood boils down to the question of whether or not piksari can transcend its ties to Korea’s hybridity. Mickey 17 represents a compromise: Bong retains his structural critique of capitalist exploitation, and trades piksari's geopolitical specificity for a sci-fi setting and broad satire. Unfortunately, the trade-off fails to make up for the absence of daring formal transgressions and, unlike the precisely controlled chaos in his other great films, this one just feels overstuffed. But it concludes with a brief return to form. In the mostly feel-good epilogue, in which the 3D human printer is destroyed and humanity resolves to live alongside the native lifeforms through parliamentary democracy, Bong inserts an unsettling scene: Toni Collette’s character turns up to reprint her husband, the fallen fascist leader. The scene is soon revealed to be nothing more than a bad dream, but in this moment of dire crisis for American democracy—and for Korean democracy, which, even if only for six hours, was threatened by the proclamation of martial law on December 3, 2024—the horror of a despot’s return feels more lucid and believable than the optimistic ending that unfolds after Mickey wakes up. Is this happily-ever-after only his wishful thinking? The jarring intrusion of the nightmare into what is otherwise a standard blockbuster ending opens up an alternative interpretation, just as Kang-du’s dreams redefine the political dimensions of The Host. Perhaps the global renaissance of electoral fascism renders piksari accessible to anyone living in withering neoliberal states where, in the words of Marx, capitalism and class struggle enable “grotesque mediocrity to play a hero’s part.”10

- Jung Sung-il, Desperate Devouring (Badabooks, 2010), 327–368. ↩

- Lee Jung-Eun, “U.S. Military Refuses to Hand over Suspect,” Dong-a Ilbo, January 28, 2002. ↩

- Stéphane Delorme, “L’art du piksari,” Cahiers du cinéma, no. 618 (December 2006), 47–49. ↩

- Im Hwa, “Discourse on Joseon Cinema,” Chun-chu (November 1941). Translated into modern Korean and reprinted in Baek Moon-im, Im Hwa’s Cinema (Somyung Books, 2015), 282–293. ↩

- Incidentally, Im was critical of the literary output of Park Tae-won, Bong Joon-ho’s maternal grandfather. In a 1938 essay, “Discourse on the Social Conditions Novel,” he commends Park’s novel Scenes from Ch'onggye Stream (1938), a work of literary naturalism in the vein of Emile Zola and Guy de Maupassant, for its vivid portrait of colonial Korea, but calls its fragmentary structure “an empty mosaic that barely coheres into a novel” and its political detachment “gray-colored pessimism that renders the novel no more than gossipmongering.” ↩

- Yoo Un-seong, “Transplantation and Parasitism: Rereating Im Hwa’s Film Theory in the Light of Bong Joon-ho’s Parasite,” Sseum, no. 10 (March 30, 2020). ↩

- Many Korean critics and film historians use the term malocclusion, which refers to a misalignment of the teeth, when discussing the work of Kim Ki-young, who studied dentistry in college. ↩

- Geum Dong-hyun, “Kim Ki-young’s (Bastard) Children: An Interview with Kang Chul-woong,” ma-te-ri-al, no. 6 (March 2022), 20-23 ↩

- Yoo Un-seong, “Transplantation and Parasitism,” Ssuem. ↩

- Karl Marx, preface to the second edition of “The Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte” (1869). ↩

![Behaviour Interactive to Publish Killer Clone Game ‘It Has My Face’, Coming This Year [Trailer]](https://bloody-disgusting.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/ithasmyface.jpg)

![The Top 10 “Phantom” Movies and Media (We Think) [Halloweenies Podcast]](https://bloody-disgusting.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/phantom-list-and-movies.jpeg)

![Ideal Women [THE FAMINE WITHIN]](http://www.jonathanrosenbaum.net/wp-content/uploads/2014/03/TheFamineWitin-ad.jpg)

![Bravery in Hiding [on LUMIÈRE D’ÉTÉ and LE CIEL EST À VOUS]](http://www.jonathanrosenbaum.net/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/lumieredete3-300x168.jpg)

![A Couple of Kooks [MY BEST FIEND]](https://jonathanrosenbaum.net/wp-content/uploads/2011/11/my-best-fiend-bluray.jpg)