Scriptnotes, Episode 683: Our Take on Long Takes, Transcript

The original post for this episode can be found here. John August: Hello and welcome. My name is John August. Craig Mazin: Aww, my name is Craig Mazin. John: You’re listening to episode 683 of Scriptnotes. It’s a podcast about screenwriting and things that are interesting to screenwriters. Today on the show, what if we […] The post Scriptnotes, Episode 683: Our Take on Long Takes, Transcript first appeared on John August.

The original post for this episode can be found here.

John August: Hello and welcome. My name is John August.

Craig Mazin: Aww, my name is Craig Mazin.

John: You’re listening to episode 683 of Scriptnotes. It’s a podcast about screenwriting and things that are interesting to screenwriters.

Today on the show, what if we just never cut? We’ll discuss long takes and oners and the decisions writers need to make when implementing them. Plus, we have news and follow-up, and listen to questions on movie theater lights and outlining for improv. In our bonus segment for premium members, Craig, how do we manage our phones, and how do they manage us? We’ll talk about the growing, maybe, movement towards dumber phones.

Craig: Yes, I’ve just been reading about it.

John: Yes, so we’ll get into that.

Craig: We’ll dig in.

John: All right. Craig, we’ll start off with the news that your show just debuted. Congratulations on season two.

Craig: Thank you. Obviously, we’re recording this a little bit ahead of time, so I have no way of knowing if people watched it or if they like it. I hope they did. The culmination of two years of very hard work, and so begins a month and a half of The Last of Us, and hopefully people like it.

John: Yes. If people want to hear more about The Last of Us, they should listen to you on the other podcast, the official HBO podcast.

Craig: There’s an official HBO podcast, so the first episode should be out now. It comes out right after the show airs on HBO, which I believe is at 9:00 PM Eastern time, 6:00 PM Pacific time, and wherever it runs, for instance, at Sky in the UK. That podcast is hosted, once again, by Troy Baker, who voiced Joel in the video game, and it’s Neil and me, or I should say it’s Neil and I. It is I. Probably a couple interesting guests along the way.

John: Cool, great. We’ll look forward to listening to that. We have news of other kinds. Sundance Film Festival, which is my festival that I love, two of my movies debuted there, The Go and The Nines.

Craig: They’re walking.

John: They’re moving.

Craig: They’re walking.

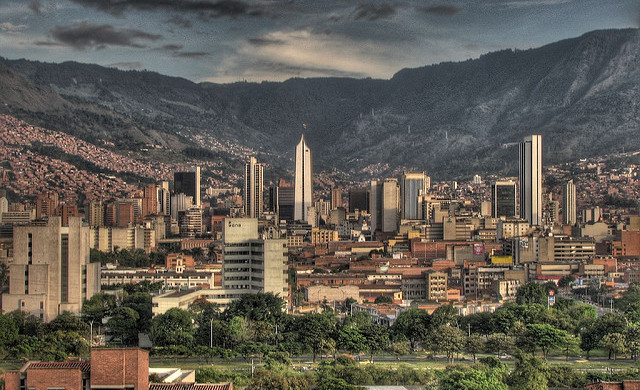

John: We always associate Sundance with Park City, Utah. That’s where it was born and raised, but it’s now moving to Boulder, Colorado, my hometown, the place where I was born and raised.

Craig: Oh, well, that’s amazing. It’s moving for a pretty clear reason.

John: A couple of good reasons. There’s the political aspect of it. Utah is already conservative, but it’s moving in a more conservative direction. I think the inciting incident really was that Park City itself was not a great home for the festival in terms of the people who live there were tired of being overrun every year by people coming in here and going.

Craig: All this money is making us crazy. Listen, people who live in a town like that deserve some peace and quiet. It may be that Sundance was looking to skedaddle. When the Utah State Legislature decided to ban the flying of the pride flags on state buildings or schools or display of any kind, at that point Sundance said, “Yes, we’ve had it.”

John: There’s also a financial aspect. $34 million in tax incentives over the course of a few years, which is really helpful. Also, as a person who grew up in Boulder, it’s just a really good fit for Sundance in terms of logistics and space and be able to do things. Have you ever been to Sundance Festival?

Craig: I’ve never been to Sundance. Many, many years ago, I was invited to go do, I think, what you do, which is to be a mentor. I couldn’t do it because I was in production. That was probably my window to go and do that. I’ve never been to the festival. I’ve also never been to Boulder, Colorado.

John: Yes, it’s an incredible city.

Craig: Feels like maybe I should go.

John: You should go to Boulder, Colorado. The festival and the Institute are different things. The Institute runs the labs, which is what I’ve been an advisor to for 20 years.

Craig: Then there’s the film festival, which is the competition.

John: Which is the competition. The labs are always taking place at the Sundance Resort, which is this little tiny bubble oasis, like you’re literally on the mountain and away from everything else. The festival happens in Park City, Utah, which is over the last 20, 30 years to become an incredibly popular ski destination and expensive for a lot of reasons.

One of the real challenges of holding a festival in a place like Park City is that they’re just not set up for all that stuff. Getting around is really challenging. For The Nines, I ended up hiring a PA who was just like my driver to get me places, because I just needed to be places, and there was nowhere to park. His job was just to–

Craig: Drive you and wait. Infrastructure is definitely a thing. It does seem to me like part of the– I don’t want to say charm, but character, I would suppose, of these festivals can seem to feel similar in that it’s not really designed for this insanity. The insanity is part of the fun of it, I guess.

John: Yes, and so it will be a different experience in Boulder, which is just bigger and more spread out, but also much easier to get around than Park City is going to be. There’s not the mountain right there that you’re going to immediately go skiing. You can go skiing out of Boulder, but it’s not a choice of like, “Do I want to go to this movie or ski for two hours?” That’s not–

Craig: I don’t want to ski for two hours. I don’t want to ski for two minutes. I really don’t. There’s a documentary I saw, just a bit about the ski industry and how the people that run Vail have basically taken it over and how just screwed up it all is.

John: Yes, the Ikon Pass, which is all-powerful.

Craig: Yes, it’s a nightmare. The whole thing is a nightmare to me. I’m literally, why? In the end, you’re just going down. That’s all you’re doing-

John: It’s just gravity.

Craig: -going from high to low.

John: It’s great, though, I love skiing.

Craig: You’re German.

John: Yes, and I was also born into it. I was born in Colorado. I was a little kid without poles. It all feels very natural.

Craig: It’s in your blood. I feel like anybody from Germany, Austria, Switzerland, they’re supposed to be schussing.

John: Sundance Film Festival, this next year will be the last year in Utah, and then it’ll will move to Boulder. I’m excited because there’s films that I know are going in production that I want to really see. I just don’t go to Sundance because the Park City is such a hassle. I will absolutely be going probably almost every year to Boulder.

Craig: Even just to get to Park City from the Salt Lake City Airport is–

John: It’s a hassle.

Craig: Yes, and now you just land at Boulder.

John: You don’t actually land in Boulder, you land in Denver.

Craig: Oh, you do?

John: There’s a little airport in Boulder, so fancy people will fly directly into Boulder.

Craig: Why do I feel like Boulder is a real city that deserves an airport? How many people live in Boulder?

John: 100,000.

Craig: Oh, you’re kidding. Oh, in my mind, Boulder was a big city.

John: Oh, it’s not a big city at all.

Craig: In my brain, it was like a million people.

John: An interesting thing about Boulder is that it’s so close to Denver that there’s the danger of it growing into Denver.

Craig: It’s like a Fort Worth to Dallas?

John: Kind of. Yes. What Boulder did is they bought up this belt called the Greenbelt all the way around the city to keep it as open space so that it won’t actually grow into Denver.

Craig: To keep those damn Denverites out it.

John: Absolutely. There’s pros and cons to it. It’s nice environmentally. It’s nice to create the experience of being in Boulder as not being a part of the megalopolis, but it also drives up the prices of real estate in Boulder because everyone want to live in Boulder.

Craig: Is Boulder just as elevated as Denver in terms of altitude?

John: It’s high, yes, or right up against the Foothills, yes. A mile high, so you do have to–

Craig: The things I don’t know.

John: Lower altitude than Park City would be. That’s something.

Craig: Yes, breathe a little easier.

John: That’s not the only changes in the world. The Nicholls Fellowship has changed as well.

Craig: It has.

John: Drew, talk us through what is changing with the Nicholls Fellowship.

Drew Marquardt: Yes. The program will now exclusively partner with global university programs, screenwriting labs, and filmmaker programs to identify potential Nicholl Fellows. Each partner will vet and submit scripts for consideration for an Academy Nicholl Fellowship, and The Black List will serve as a portal for public submissions. All scripts submitted by partners will be read and reviewed by academy members.

John: Basically, what happened before when you submitted to the Nicholls Fellowship, which we’ve talked about on the show before, it’s probably one of the only screenwriting competitions that’s worth entering because people actually do really pay attention to who wins the Nicholls.

Craig: Yes, it is kind of the only one.

John: Basically, they’re no longer just have an open door to just submit your script and have it be read. Instead, it has to go through a program. It either goes through a university program or it’s going through The Black List first, but it’s not just an open door like everyone’s interested in your stuff.

Craig: Why?

John: We have some listeners who write in with their concerns. My suspicion is that it’s actually just become impossible to sort through how many people are applying, and they’ve just run out of manpower to do it.

Craig: Are these university programs and The Black List serving as a gatekeeper?

John: Yes.

Craig: I don’t love that at all. In fact, I hate it. We’ll get into that.

John: Our listeners have spoken about that. Give us an example. I know we have Elle here in the WorkFlowy.

Drew: Yes, Elle writes, “This reduces opportunities for screenwriters. Whereas both a Nicholl placement or a blacklist aid could get writers reads before, now there’s effectively only a single path. This also seemingly weights Nicholl entries towards college-age students and those who can afford film school. By the way, about 100 Nicholl readers just lost their side gigs. How will this affect them?”

Craig: What a fantastic question/statement that summarizes why I hate this. I’m not suggesting that the Academy, which I am a member, although not an administrative member like yourself.

John: Oh, I’m not an administrative member either.

Craig: Oh, I thought you were in a committee or something.

John: I was on the writers committee for a time. We’re both in the writers group, but I don’t think I’m actually on any committee at this moment.

Craig: Oh, okay. We’re merely citizens of the Academy. The Academy is a nonprofit organization. It does need to manage finances, but it seems to me like perhaps, I don’t know, increasing the price of submission maybe, or just figuring out how to raise money to support it might be a better thing than this, which I think undermines the authenticity, the value of winning a Nicholls. The whole point was anybody who wrote a great script could send it, have it be read by the 100 people who were being paid, and have a chance.

I don’t like the idea that universities are involved at all. At all. Nor do I like the idea that The Black List, which is not a not-for-profit business, is involved at all. That’s a profit business. I don’t think these things– I don’t understand. This just feels like they gave it away, I got to be honest with you.

John: I hear all of that, and I agree with a lot of it. I want to take the con side, is that I suspect that the choice was do something like this or just get rid of it altogether. I suspect they were bumping up against this is an unsustainable situation.

A thing I’ve read recently about the places that have open submission policies like science fiction magazines with open submission policies are just flooded to the degree that they cannot possibly sort through all the things, so they basically just had to close their open submissions because everything gets sent in, and it’s not just like the writers who are aspiring to do this thing, but it’s also just like it’s AI slop that they’re getting, and they’re getting stuff sent in.

I can see this as a defensive move. I agree that it limits some opportunities, but I would also question maybe the Nicholl Fellowship was not as useful as we might think it was, or it’s been increasingly less useful to people breaking in now.

Craig: If it has been increasingly less useful, I think the less usefulness has dramatically increased to remarkably less useful, because now it just feels like they’ve outsourced it.

The whole point was it was the Academy doing it. Even if the Academy was employing people, of course, to read, but the academy had control over that, and there wasn’t, for instance, a built-in bias like pro-university students. I don’t think that is fair. It doesn’t make sense, nor does it make sense to require people to go through a profit business in order to be read to–

John: Again, this is a mild defense, but if the Nicholl Fellowship was charging a fee for submission and Black List is charging a fee for submission, yes, they’re outsourcing it to it, but if it’s the same fee that you’re charging, does it really matter who you’re writing the check to?

Craig: Yes, because I don’t know how The Black List manages this, but the point is, The Black List exists to make money. If the Nicholls Fellowship theoretically charges, let’s say, $50, and they take all 50 of those dollars and put them into people reading the scripts, people judging the scripts, and they take none for themselves, and The Black List says, “We’ll do the same thing for the same $50, but we’re here to make money,” well, let’s just say that they are spending all those $50, they’re spending $20 on it. Now what happens?

I don’t like it, and I do feel like in our business, which somehow manages to raise money for everything, if the Academy was in that situation where their back was against the wall, it was like, we’re killing the Nicholls, or we’re outsourcing it, or can we find some benefactors? There are writers we know, personally, who could write a check on their own to fund the Nicholls, or to at least subsidize it. I don’t love this. When I say I don’t love this, I mean despise it.

[laughter]

John: All right. We’ll follow up as we hear more about this. I expect that the controversy will continue.

Craig: Yes. I’m on your side, everyone who is out there, except for the people that like this. I’m against you.

John: Let’s do some follow-up here. We have more on editors not reading scripting notes.

Drew: Nate writes, “I’m a comedy editor. I’ve worked on things like Somebody Somewhere, Drunk History, Another Period, and I always read the notes as I’m putting together the first cut of a scene.

Craig: Here we go.

Drew: In my comedy sphere, I don’t know anyone who doesn’t refer to them. They contain useful information about how many setups and takes I should have in my bins. I rarely have directors or producers ask which takes are their circle takes, but I do keep that info handy in case I’m asked. However, the majority of editor logs are not very useful. They tend to focus on minutiae like prop continuity, which doesn’t matter much unless the error is distracting. 99% of the time, we’ll choose the take based on performance, not on continuity.

Mostly what I’m looking for in the notes is information that might explain the intended purpose of a particular setup, especially in more complicated scenes. I know it’s impossible for a script supervisor to know everything that will and won’t be important during the edit, but if they want to ensure that their notes are being read, include as much information as possible in their notes.”

Craig: Yes, because they don’t have enough to do already. Yes, because they’re not already doing 12 jobs. This is so infuriating to me, how many exceptions to the rule we’ll be writing in. It’s like, look, and I was pretty clear about this. I’m not saying no editor looks at these things, and I appreciate he’s saying everyone in his comedy sphere. I worked in the comedy sphere for 25 years, never saw it happen once. Saw me saying, “Can you please go to the notes and see what it said there?” Lots of times. Sometimes they didn’t even know where the F-ing book was. They had to go find it.

It’s so infuriating to me, but no, of course, there are people who do it. My point is, nowhere near enough, the vast majority of people I’ve worked with don’t, and I understand why. Again, to reiterate, editors should have a chance to just see things without any spin on it, but in defense of the script supervisors, they do put a ton of information in there that I myself am constantly saying, “Hey, well, what did the notes say? Didn’t the notes say something here about something?”

The idea that they should be sitting there writing lots of things for the editors, they don’t have the time to do any of that. This is why editors should be forced by gunpoint to sit on sets, just the way writers should be forced at gunpoint to sit in editing rooms. We all need to see what the other people are doing to have some A, empathy, and B, better connection to the other parts of our job.

John: Agreed.

Craig: Gunpoint is the key.

John: Craig, as a show owner, you have the power of gunpoint, so you can be able to do things. Would you take an editor up to set?

Craig: I have. There are times where I insist on it. We have our editors for season two, it was again, Tim Good and Emily Mendez, and then we also added the great Simon Smith, who I worked with on Chernobyl. One thing that’s important to me is to have them up there in Vancouver with us while we’re shooting. They don’t need to be there in theory, but I like them there because A, I can come by and we can sit together, but they also have access to all of us. They can ask us questions as they’re going.

Then it’s particularly important to me when we’re doing anything that is wildly out of order because of the nature of the schedule, or if we’re redoing something because we have to fill a bit in that I don’t like, to have the editor there to make sure that it is in fact going to meld in seamlessly.

Because there are times where, just because of production exigencies, you’re shooting the middle of the sequence seven months after you shot the rest of it. It’s good to have an editor there, and particularly when the editor and the script supervisor are together, which is amazing, so I can turn to them and go, “I think this is going to blend in.” They’re like, “Yes, it will.” Yes, I love having the editors on set.

John: That’s great. That is it for follow-up, but let’s do– We need a new term for follow ahead, future planning.

Craig: Ooh, chase up.

John: Chase up or chase down.

Craig: We’re not following, we’re leading. Lead up.

John: Lead up. Yes, lead up.

Craig: Lead up.

John: Preview. An upcoming episode, I’d love to talk about those first jobs in the industry and the things that you do in those entry-level jobs. I would love our listeners who have experience in those positions to write in. Specifically, what I’d love first is for them to write in about their experience as the PA runner who is responsible for making the lunch run.

Actually, I’d like to focus on the lunch run because it’s a very classic first job where there’s a writer’s room, there’s production, there’s whatever, post, and your responsibility is to take the order for what everybody wants for lunch, go out and get that, and bring it back and provide it to everybody and not screw it up.

It seems like the potential for screw-ups is very high. There’s also the logistics and how you pick restaurants and how you interface with those restaurants. Stuart Friedel, who was my assistant for a long time, we used to do a lunch run, and it was through him that we first encountered Paul Walter Hauser, a fantastic actor who was working at a restaurant that Stuart was picking up food from.

Craig: Was it Mendocino Farms?

John: I think the orders were from Mendocino Farms, but I think Paul was working at a coffee shop next to it.

Craig: Oh, I see. There is an entire episode to be done about the Mendocino Farms Assistant Industrial Complex and how the two things feed into it. It’s like Mendocino Farms was created for assistants. It’s incredible. I hate it. I do not like it.

John: Also, they changed their menu. I will fall in love with something on their menu, and they will just get rid of it. A sandwich study in heat is no longer on the Mendocino Farms.

Craig: It was called a sandwich study in heat?

John: Yes. It was that chicken sandwich with the spicy sauce. Craig: Oh, I never got that, probably because I thought it was mayonnaise. A lot of times, when they say spicy sauce, it’s mayonnaise. [crosstalk]

John: It wasn’t mayonnaise.

Craig: I always get that salad.

John: For listeners outside of Los Angeles, Craig, can you describe Mendocino Farms?

Craig: Yes. Mendocino Farms is what you would call a fast casual restaurant, does a lot of takeout work. It concentrates on the staples, vaguely healthy versions of things, sandwiches, salads, soups. Because it has one of those classic things in every possible category, including vegetarian and vegan, and because the menu is not massive, assistants just go, “And today for lunch, room full of 20 writers, it’s going to be Mendo.” Everyone’s like, “Ah, fine,” because it’s the least objectionable choice.

John: Yes. It’s at a price point that makes sense for a room to order from, so for all those reasons that it’s useful and they’re discreet foods. Again, I’d love for our listeners to write in to talk about what tends to work well and what’s like, “Oh my God, this is an absolute nightmare for us too.”

Craig: This is great. In fact, if you are currently working in a position where you are getting lunches, you’re ordering lunches for rooms, I’d love recommendations for things other than Mendocino Farms. Obviously, look, there’s Olive and Thyme in Burbank. There’s some that you always keep going to, but I’d love the– Give us your secrets. Let’s spread the wealth around.

Drew: Is Fuddruckers still in Burbank?

Craig: Fuddruckers, the hamburger place?

Drew: The hamburger place. I hated that lunch run. That one was the worst.

Craig: Maybe it is. It was out over by Ikea and all that stuff. Nobody wants to go there. Try and keep it in Toluca Lake.

John: True. You’ve done many a lunch run. Any other guidance or things you’re looking for out of this segment?

Drew: Oh, God, no. I’m curious to hear all the other options, and I also want to hear horror stories. I’m really interested in the lunch run horror stories.

Craig: Yes. You know what? For horror stories, if you don’t want to get sued by a restaurant, you can always say, There is a restaurant in, and give us a vague neighborhood. Then tell us your horror story, because there is something beautiful about early day– Did I ever tell you my assistant horror story?

John: No, tell me this.

Craig: I was actually an intern. I wasn’t even an assistant. I was an intern. Folks, this was in 1991, and pre-LASIK, as you might imagine, and I required glasses, or I cannot see. I am a summer intern through the Television Academy for Dan McDermott, who’s the head of current programming at Fox Network. I would get a lunch break, but I had stuff to do. I had a lot of Xeroxing. Things to do. It was my lunch break, and I went to the bathroom. This was on the third floor of that horrible Fox executive building, which is old.

They had those– you know toilets that are connected to some sort of horrible suction system, right? I go to pee, and there were people using the urinal, so I had to go into a stall. I’m standing there, I pee, and I lean over to flush, and my glasses fall off my face, go into the toilet, the suction just takes them down, and they’re gone.

John: Incredible.

Craig: For a moment, I was like, my brain couldn’t handle that something that permanent had occurred. Then I was like, “What do I do?” I don’t know what to do. I don’t walk around with an eyeglasses prescription. I’m now struggling with bad vision. I find a Yellow Pages. There’s one place that has an ad that’s like, “We’ll give you glasses in an hour,” and it’s downtown. I am not familiar with Los Angeles. I know how to get from my bad apartment on Pico and La Cienega to Fox. That’s it.

John: Which is on Pico.

Craig: Which is on Pico. I know one street. I get in my car. I can not see. I get on the freeway. This is before Waze, before the internet. I have written down on a piece of paper where I’m supposed to go. I head east on the 10 freeway. I miss the exit because I can’t see it. Now I’m on the Five South, and it seems that I’m on my way to San Diego. I pull over. I am nearly in tears. I don’t know what to do. A cop comes up behind me. I’m like, “Hey, yes, I’m just trying– I got lost.” He looks at my piece of paper, and he’s like, “Okay, here’s what you do.” I do it. I get to this place. It is a bad neighborhood.

I wait there, there’s crying babies. Then I got these horrible chunky glasses and drove back, finished my day, went back to my apartment, where I lived with two other guys. We didn’t have couch. Sat down in front of the TV. The worst day ever. Took my glasses off to rub my eyes. One of my roommates came in, stepped on them.

John: Incredible. [laughs]

Craig: [laughs] Again, I just looked at them like, “This cannot be. What a sweaty day.” You know what? This podcast has never been about telling personal stories, but I think people needed to hear that one.

John: Oh, of course.

Craig: Because if you’ve ever been in one of those days, just know the guy who does the podcast you listen to, yes, been there.

John: All right. You just told your assistant, your intern-

Craig: Intern nightmare.

John: -glasses story. I may have told this on the podcast before, but I was interning at a Universal, so this is somewhere between my two years at Stark, and I was the intern below three assistants. There were three assistants above me for my boss, so there was nothing for me to do. You talk about Xeroxing.

Craig: You didn’t even get to Xerox?

John: No, I got to put some stuff in some file folders that would never be looked at again. That’s all I did. We had to go to a screening across the lot, and my boss was going and the assistant was going to drive her in her car, but I was supposed to take the golf cart in case my boss wanted to come back to the building without her car, so great. We’re waiting, we’re on the 10th floor of the Black Tower at Universal, waiting for the elevator. My boss takes off her glasses, reaches over, untucks my shirt, wipes off her glasses, and then puts them back on.

Craig: You were just a glasses wipe for her?

John: I was a glasses wiper for her, and I was so thrilled. I was so excited because this is a story. As it’s happening, you’re like, wow–

Craig: I get to keep this.

John: I get to keep this. This is incredible.

Craig: It didn’t feel to me at the time that I was living a story. What I felt was just a lot of hot fear and confusion. When all was said and done, I was like, “This is one to hang on to.” This is life, man.

John: Yes. Let’s get to our marquee topic, which today is long takes and oners. It’s the sense where we are in a scene, or sometimes over the course of a whole movie, and we are not cutting. We’re basically getting over the whole editorial department, or at least large parts of the editorial department. Instead, we are staging action in front of the camera, and the camera’s just going to keep rolling as we’re going through everything. We should define our terms a little bit.

A long take is just that. It’s not necessarily flashy. It could just be holding a two-shot for the course of a scene. A oner to me implies there’s camera choreography. There’s a whole plan for how we’re going to move through a space and do this all as one shot for something that would naturally, normally be multiple shots.

Craig: Yes, the entire scene takes place or multiple scenes take place in one camera move, and there is no other option.

John: Yes. Let’s talk about what the other options would normally be, which is coverage. Craig, talk us through what you mean by coverage.

Craig: In very simple terms, a master shot is a wide shot in which you see all of the people who are involved or all the action, all the stuff. You get a full view of it, and you can have master shots from two different sides of things. Coverage is then where you get closer and you change your angle so that you have individual shots of people in the scene. Medium shots, close-up shots, insert shots of somebody putting a coffee cup on a table, things like that.

You have stuff to cut to and you have ways to shape a scene so that in visual space, you understand, okay, here’s how the audience might feel looking at this wide, here’s how they might feel with a more intimate view, and so on. Coverage allows you to edit and shape a scene. When you’re doing a oner, there is no coverage. The coverage is what you decide to do there on the day with the camera, the end.

John: I think we should specify is generally we think about coverage as okay, now we’re moving into coverage. We’re out of the master shots, we’re into this. Obviously, you can set up with multiple cameras so you’re getting coverage at the same time as the master shots with careful planning.

Craig: Yes, no question. This happens all the time. Depending on the nature of the scene, you may be able to avoid coverage almost entirely if you have three cameras going and the people are arranged in a certain way doing certain things, or sometimes you do master and then cross cover, where you can get both sides of the conversation at the same time.

John: Absolutely. Examples of shows that are doing oners are these very long takes, the new Netflix series, Adolescence, Stephen Graham, and Jack Thorne.

Craig: The Great Jack Thorne.

John: Great Jack Thorne, Scriptnotes guest. On that show, it’s four episodes long. It looks like their basic plan was for every episode, they would have five shooting days, and they would just shoot as many times as they could to get it right. Episode one, what we see is take two. Episode four, that was take 16 we’re seeing to get that finished. If you watch the show, you’re pretty aware quickly that we’re not cutting because the camera is following characters and then following another character. It’s just-

Craig: Fluid.

John: -fluid. It’s just always moving. There are times where it does extraordinary things to keep it going. Contrast that with The Studio, which is the new Seth Rogen, Evan Goldberg, and others show, which has very long takes and isn’t cutting very much, but it’s not the illusion that it’s all one continuous moment.

Craig: I guess the first question would be why? Why do people do this? I’ll editorialize after I give the non-editorial version.

John: Yes, please.

Craig: The non-editorial version is that there are some scenes, moments, or in the case of Adolescence, an entire thing, where you want to be immersed in such a way that you are forced to watch this one camera. You start to realize that this camera’s trapped you. Coverage does keep things fluid, and it changes perspectives and moments, and it gives you a sense that the show is always, or the movie is privileging you. One extended take, a oner, takes that away. You are now a prisoner of this moment. Even when you do long takes, you can start to– and that is, I think, ultimately why a lot of people choose to do it, and that is a good reason to do it.

The other reason to do it is because the sequence is about moving through an interesting space to arrive at a conclusion. The classic example is the tracking shot in Goodfellas, where Ray Liotta takes Lorraine Bracco through this nightclub, [crosstalk] through the kitchen, all around to see how this guy had this backdoor into everything, and eventually arriving at a nightclub table, sitting down, and then seeing the great Henny Youngman.

John: Before we get into the cons, let’s talk through some more of these pros. You talked about immersion and that sort of realism and the way that it forces the viewer to pay attention and to focus. A thing I noticed with Adolescence is, my husband and I will sometimes– We’ll be on the couch watching a thing, and we might look at our phones, might watch something else, but because we were looking for the seams, we were just completely paying attention at all moments, which is really useful.

That sense of place and sense of geography you get through a continuous tracking shot is really something. You actually understand how a space fits together when you’re not ever cutting and you’re never actually changing point of view. Or if we are looking at a different direction, we see ourselves moving, you just understand something better than you could off of a series of still images to get the sense of the geography.

Craig: It also requires the production generally to create a 360 environment. Pretty typical when you’re doing a scene traditionally, let’s say it’s two people talking in a cafe, and you don’t have a location, you’re building the set. There’s going to be a wall– You’re going to build three walls. You’re not going to build the whole thing because the camera needs to go somewhere, and also, you’re not going to look back that way. You’re looking forward and across and across.

When you’re shooting a oner, as people move around, you’re going to need to move around, which means a complete set, either on stage or in a location, you need to make sure that everywhere you look is clear. This is harder than you think-

John: Oh my God, yes.

Craig: -because people who are making things have to go somewhere. There’s a lot of technical stuff, including people watching the monitors, cables, lights, all of the– how do you do all that? What oners do is force away a lot of the movie artifice and really embed you in a space.

John: Yes, for better and for worse. That makes it more difficult. I would say, in the pro column, it’s a mixed pro, it’s narrative efficiency. If you’re writing something that is going to be shot in a long take or as a oner, you’re going to have to think about how do I get all this information in here without the ability to cut to something else. That can be good, it’s a challenge for sure.

Production efficiency, there are situations in which you can get through a lot of material in a oner that you could take longer to do if you were to do in traditional coverage. Because you’re forcing yourself to do things a certain way, that 16-page scene could be shot in 16 minutes rather than three days, but it’s much riskier to do it that way.

Craig: Yes, no question.

John: Emotional continuity, and so if we are with our actors and the camera’s on them the whole time through, we’re going to see all those micro things happen and the changes there, if it works well, I think can be more immersive because we saw them get to that place and there was no cutting away as we saw those things happen and that can be nice too. There’s a lot of cons, and so we should really talk through the cons here.

Craig: So many cons, and now, a little editorializing. I hate these. Now, it’s not that I haven’t done them before. We did one in Chernobyl, and it was there for a reason, and it made sense for that moment, we thought. There is the whiff of directorial wankery about oners. There’s something in the water at the DGA where people get very excited about oners, and I don’t know why. There have been some incredible oners that I didn’t realize were oners. Those are my favorites. Spielberg does a few that are amazing.

It’s this thing of like and we’re going to shoot it in one where the director gets a chance to be like, “Hey, everybody, this is about me and it is about freezing my directorial choices so that no one can screw with them.” The problem is that A, lot of scenes will play better with editing because they have a tempo, they have a pace. There are things inevitably inside moments that you wish maybe we don’t need. Maybe I don’t like that line. Maybe I need to add something in. You can’t. It’s a oner, you cannot edit, there’s no escape, and you talked about catching things on actors’ faces. There’s a whole lot you miss. In fact, you miss most things because you can’t show people listening, or if you are showing them listening, you can’t show the other person talking.

John: Absolutely.

Craig: If you want to, the camera has to move around, which I find takes me– It’s like I’m in the room with the director, and that’s why I generally loathe these things. I think they just lock people into weird spaces. If you shoot something and edit it properly, it will feel like a oner anyway because it’ll be so smooth. That’s my editorializing.

John: Absolutely. You talked about the sense that you feel the heavy hand of the director. You can feel the heavy hand of the director. If you’re noticing that it’s a oner, you’re probably feeling that, and it also means that the scene has to serve the camera versus the camera capturing the scene that’s happening in front of them if it’s not done artfully.

Craig: Also, lighting is really tough. This is really tough.

John: You can’t optimize for everything.

Craig: No.

John: A thing I noticed about oners and long takes is you end up with some unmotivated character movement. You see actors reposition themselves in a scene because they need to, then actually motivate the camera to move around because they need to change stuff around. It’s like, well, why did you just stand up and move there? The scene didn’t tell you to do that. We needed you to do that.

Craig: No, and you start to feel a little bit like you’re watching a play, except it’s not a play because I’m not there. Again, the parts of this that are– I understand why artists like it, primarily is we’re protecting our work. No one can mess with it because there’s no way to cut anything. The downside is there’s no way to cut anything. No one can mess with your work, and it becomes a play, except I’m not there. I don’t have the excitement of the live performance. I’m still watching it on TV. If it is done really, really well, it can be amazing.

This is why people have really, I think, gotten excited about Adolescence in part because it actually does it well, and because I think there is something about it that does compel it. Look, I’ll be honest, and I would say this to Jack, if he were here, I’ll say it to him the next time I see him, and I know what he’ll say. He’ll stammer and go, “I’m sorry, I’m sorry. I disagree, but I’m sorry.” That is, I think it would be better if it weren’t like that. I would prefer to see that show edited and shot traditionally because I feel like I’m missing things.

John: Let’s think about Adolescence. We’ll have Jack on the show at some point to talk about that, but if we hadn’t done the continuous take approach but had kept with the idea of continuous time, so basically it’s all taking place within this same limited period of time, would it feel the same? It would feel similar. It wouldn’t feel–

Craig: Look, here’s the funny thing about time. If you play something in real time, you can get away with it for a little bit. After a while, it starts to feel like, “Oh my God, this is just like real time.” The most suspenseful things, the things where I’ve always felt time squeezing down on me, were manipulated by editing because film, cinema, television, whatever you want to call this medium, works on trickery. The entire thing is trickery. Down to intermittent motion and the fact that we’re watching 24 still frames every second. The rooftop scene at Chernobyl it was important for us to say, “These guys had 90 seconds.” That’s a reasonable amount of time to do this because it was purposeful.

John: Let’s talk about the purposeful things because I have a thing in something I’m writing, which it’s scripted as a continuous take or the illusion of a continuous take. It’s specifically because we have characters who are moving from an ordinary conversation. They notice one thing, it’s a little bit amiss. They react to that one thing. They start to backtrack. They realize they can’t backtrack, and things go worse and worse and worse and worse and worse for them. That is a good to me argument for a continuous take because, oh crap, we have that sense of adrenaline being in the space and not knowing how to get out of it.

Craig: Trapped.

John: Trapped.

Craig: The camera has trapped you, and that similarly, the camera has trapped you in those 90 seconds. I will tell you that in the first episode of Chernobyl where we follow some of the people from the control room as they move through the now exploded facility trying to figure out what’s going on, I originally wrote that in a wanky way to be like this oner where we would follow somebody and then we would fall, the camera would go down through a hole in the floor and find somebody else. Credit to Johan Renck. He was like, “Yes, it’s going to be wanky.” He was right because we could do so much more, and we can also emphasize moments. They can slow down, and then other moments can speed up.

John: You look at Adolescence and there’s moments where it does slow down and we do focus on this, but those are all really baked in and you’re counting on, the camera’s going to land at the right moment and the actor’s going to find this right space and it’s all going to make sense and then we can do on the next thing. I think Adolescence does, it’s like there is still music which also has to be choices that have to bake in from the top.

Craig: Tricky. You do, and if you have Jack Thorne, let’s also give Jack credit, as I often do, for being a fantastic playwright.

John: Absolutely.

Craig: This feels like a melding of Jack Thorne, the playwright, and Jack Thorne, the screenwriter, and this can work. Now, it also works for four episodes. Would you watch 12 episodes like that? At some point, it would become impossible.

John: As we talk about the melding of film and plays, you brought up Doubt. We’ll put a link in the show notes to the scene between Viola Davis and Meryl Streep in Doubt, which in the play, it’s set in an office. In the movie version, it’s set outdoors. It’s not pretending to be a continuous take, but it’s seven minutes. It’s a seven-minute scene. Let’s talk about long scenes versus long takes.

Craig: When you have a scene between two people and they talk for seven minutes in a screenplay, almost everyone is going to say, “Cut this down. This is way too long.” In almost every case, they’re correct. But there are times, and in certain kinds of movies, where a scene can be so powerful and the two actors are so good and the battling intentions are so interesting and the revelations that occur are so impactful that it earns its weight. It’s really what it comes down to.

John: It’s a short film within the larger film. There’s a beginning and a middle, and an end. We don’t know at the start of the scene that it’s going to be a super long scene, but we establish early on what the stakes are and what the two characters’ goals are in the scene. We’re incredibly curious to see where it goes. That’s why it’s successful. If it was just exposition, if it was just giving us information, it could not possibly sustain.

Craig: Correct. This is a good example of how length requires editing. You might think that’s counterintuitive if they had shot that all in one, which they could have.

John: They could have, yes.

Craig: Because it’s basically Meryl Streep and Viola Davis walking slowly and talking through a city park. They could have absolutely just led them on a two-shot, moved to the right, moved to the left, gone back to the leading two-shot, no problem. It would have been longer because there are just sometimes unnecessary pauses or the sense of being captured, where you get restless and itchy. Seven minutes where you can cut to angles purposefully to make, I don’t know, to make the impact come across the way you want. The seven minutes seem shorter.

John: Two of the best actors alive, so they have incredible skills. Let’s also think about how they have to divide their focus between the two different approaches. If this was what Continuous take, they have to be in their performance, but also be aware of where the camera is and exactly what mark they need to hit at every moment. All that is clicking in their heads.

In the way that it actually was shot, they had to be aware of the performance and they do need to be aware of the camera. They do need to be aware of all this other stuff. There is choreography they have to be thinking of, but they don’t have to be paranoid about stitching everything together or the stakes are lower.

Craig: Here’s another thing that drives me crazy about oners. I know sometimes actors like them because they do get stunty and because they also know, “No matter what I do, it’s in,” right? If I do this, it’s on TV, it’s in the movie.” Actors, great actors, particularly ones who are used to working in film television understand how to change their performances subtly or not so subtly, depending on where the camera is. As the camera’s back and wider, you can get away with some larger things.

When it’s right up against your face, you want those what we call the micro expressions. Also, they understand that in a situation where you do have a walk and talk, where there is going to be coverage, they can save themselves a little bit. When the camera is over my shoulder on you, I don’t need to give you the full firepower. I need to be there in the scene. I need to give you what you need.

I don’t need to be full cry. I don’t need to be full shock. I can save it. When the camera comes around, that’s when you are there to help me and I’m delivering full impact. On a one-er, that’s it. It’s just everybody give everything. If one of you is great and one of you is not so good, oh, well.

John: That’s when you break down much.

Craig: That’s that and it’s not ideal.

John: Our takeaways here is that I think oners and long takes can be really useful when they are deliberate narrative choices. They’re choices that are serving the story, serving the scene, serving the moment, but we bristle against them as instincts for it’s more realistic, it’s more honest, it’s more true.

Craig: Right. The bottom line is, I think it’s a perfectly reasonable thing to do, but unlike other choices that we make, that one must be interrogated. You have to ask, you must ask, is this about the story or is this about ego? Because ego loves a oner.

John: All right, let’s answer some listener questions. I see one here from VP.

Drew: First a little context. VPs went to a place called Cinebistro, which is a theater where they serve food the whole time, an Alamo Drafthouse style place. VP writes, “Cinebistro seems to have a national policy of keeping the house lights up at the trailer level for the first 15 minutes of all features.

Craig: What?

Drew: “Which in my experience left the chatting audience seemingly unaware the trailers had ended and the feature had begun, ostensibly to allow for guests to finish their meals, and so the servers don’t trip over said guest’s feet as they deliver and bus plates. Here’s my question. Are studios really aware of this? Are the filmmakers, is there any sign-off or do exhibitors get a pass for keeping their doors and kitchens open? Do the guilds have anything to say about the conditions in the theaters?”

Craig: The guilds? [laughs]

John: No.

Drew: “That screen their films, including lighting, sound level, temperature, or even smells.”

Craig: I actually love how some, and it’s sweet. People think the guilds can do something about this.

John: I think DGA might have a strong opinion about it but [crosstalk]

Craig: They’ll write a sternly worded letter. The guilds can’t do anything about this. The studios, if they’re aware, are just probably grouchy about it. Hey, if those places are sending their rental fees to the studios to run those things and they’re selling tickets, which the studio gets a chunk, I don’t think they’re going to care. Just like studios don’t seem to care or did not care when projection bulbs were crappy all the time and sound systems weren’t great.

They encourage exhibitors to do things, but studios and the exhibitors are not on the same side. There’s somewhat of an adversarial relationship there. We can’t even get television manufacturers to turn the effing motion smoothing off. The idea that we could get these guys to turn their lights down– [chuckles] Forget it.

John: My husband, Mike, ran movie theaters in Burbank for many years. He had 30 screens and there was a filmmaker, a very well-known three-named filmmaker, who came out yelling that the sound wasn’t turned loud enough in the theater. Mike had to interact with him. Then I think the filmmaker had bullied the projectionist to actually turn up the sound. Then an audience member came out and found Mike and said, “It’s too loud, my ears are hurting.” A shouting match happened between the filmmaker and the audience member and so– [crosstalk]

Craig: That’s what you want as a filmmaker, is to yell at your audience.

John: I understand why filmmakers want to see the best possible conditions for their films-

Craig: Of course.

John: -but there are things out of their control. You, VP, have the choice of going to Cinebistro or not going to Cinebistro. If they do this and this is distracting, which I would hate, then don’t go there.

Craig: Don’t go there. It’s as simple as that. I understand why the three-named director did this and how that person felt. Because I pour so much time and effort into sound, into that, down to the tiniest thing. Everything is just thought through carefully because I believe that sound is as integral to storytelling as sight, maybe even more so at times.

I try and write towards sound, and then you do show up somewhere and they’re like, “What are you guys playing this through a fricking tin can? What is happening here?” Of course it’s upsetting, but I then realize there’s nothing I can do about it, nor can I do anything about the motion smoothing, which horrifies me so deeply. I just can’t believe that we let this go on, that we can’t–

Sony, which owns an entire movie studio, will send you a television with motion smoothing turned on. It’s ridiculous, but we can’t do anything about it. Which is why, in a weird way, when people complain about everybody watching stuff on their iPad, I go, “Do not complain.” The iPad doesn’t have motion smoothing. The iPad probably has decent sound, actually, if you got your earbuds in, it’s okay. It’s better than a bad theater, and it’s certainly better than the motion smoothing on your TV.

John: Let’s talk about the lights being up in a theater. My closest experience with this has probably been when my daughter was a little baby. We used to go to the Mommy and Me movies over at The Grove. On Monday mornings, the first screenings, they would show the normal movies, R-rated movies, but specifically for parents with little kids. You could actually change a diaper while a baby–

Craig: Because they figured the kid wouldn’t remember watching this.

John: Yes, and so I remember seeing The Constant Gardener as a Mommy and Me movie.

Craig: Hold on, babies love movies about the creation of the CIA.

John: Yes, and I can respect that. I feel like–

Craig: Yes, that’s different. Everybody knows the deal. Look, if there’s a baby crying, if you smell some poop, that’s what this was about.

John: Absolutely, and I think there were screenings in Wicked where they encouraged singing and other times don’t.

Craig: Listen, that’s just good old ground rules. It just comes down. If you go to a theater, your expectation, unless told ahead of time, would be that when the movie starts, the lights go down. Serve the frickin’ chicken fingers 10 minutes earlier, for God’s sake.

John: Speaking in defense of serving food in theaters, Alamo Drafthouse is a good experience and they also really take the movie-going experience seriously.

Craig: You can do both. I have no problem with it. Look, we’ve always given people food in movie theaters. It is a strange thing, but we’ve always done it. I guess it’s because theaters got to go make money. I vastly prefer people having their chicken fingers and then watching the movie to people just munching in my ear throughout. You and I also, we remember how bad theaters used to be. We’re complaining now. The thing is theaters were a nightmare.

John: Yes, there’d be stains on the screen.

Craig: Everything was disgusting. The floor was flat. If somebody in front of you was over five foot seven, you were missing a chunk of the movie. The seats were small. There were no cup holders, John.

John: No.

Craig: They didn’t have cup holders.

John: The concept had to come.

Craig: It hadn’t existed. Also, when the movie ended, everyone dropped everything on the floor. There were no– People would come in and for 10 minutes, a cleaning crew would come in and just sweep everyone’s garbage away. Listen, we lived like animals.

John: Katie has a question for us.

Drew: “When voting for the Academy Award for Best Original Screenplay, I don’t dare assume I know what people do in reality, but I believe the intended ideology is that it is judged on the draft of the script submitted and not the finished product. I spoke with someone who believed the finished product is what is to be judged, which they clarified by claiming to vote for the WGA Awards and stated that they’d never read the scripts and only watch the screeners.

Since this process is shrouded in mystery and intrigue, I was wondering if you could shed some light on what goes into voting, what your process is, and perhaps your knowledge of others as well.”

John: Fair question. You would assume that Best Screenplay, we’d be referring back to the screenplay to see which is the best written screenplay. We don’t.

Over the last 10 years, it’s become common for them to send out links to all of the screenplays so we can read them. We can read, Drew, every year goes through and pulls all those up so we can actually read those things on our phones, which is fantastic. Thank you, Drew, for that. That’s not an expectation or requirement.

Craig: No. Even when you look at what the Writers Guild credits mean, if you get written by John August, what that means is you get credit for the screenplay as shown on the screen. You’re not really getting credit for a document. You’re getting credit for the writing of the movie. We presume, and I think reasonably so, that if you are a member of the Academy, you’re good enough at this point to be able to watch a and discern what the story and the writing and screenplay elements are. That is what we generally do. Because if you go back to the screenplay, you might notice some serious differences because things do change.

John: Listen, all of the categories were judging for these awards based on what we see on screen. That actor could have turned in a fantastic performance that does not actually really reflected in the final thing because of editorial choices or because other stuff happened. That is 100% the case. Same with visual effects and stuff. We have these little sizzle reels that show us what the visual effects or special effects actually were, which is helpful. We’re just basing it on what we’re guessing happened behind the scenes based on the final results.

Craig: You also make a good point that there are times where we write things. If you look at it on paper, you may not, as a reader, get why this line is good. When you watch it on screen, you understand, oh, the screenwriter’s intention was this, it made it through the director and the actor, and it is good. I always think about one of my favorite one-word lines in movie history is in John Wick. You a John Wick fan by any chance?

John: I’ve never seen John Wick. I’ve never seen any of the movies.

Craig: I think for you, I would suggest watching the first John Wick. It’s terrific. By the way, don’t expect like– It’s not Shakespeare. But in its own way, it owns what it is so beautifully. I don’t think you need to get into the sequels, you probably– Who knows? Watch the first one. There’s this wonderful moment where Keanu Reeves plays this guy, John Wick. We don’t know who he is.

All we know is that his wife just died. He has this new puppy that she got for him to say, “Hey, love this instead of me. Because I’m gone.” He’s wrecked. This young Russian gangster steals his car, beats him up, and kills the dog. The gangster goes to sell the car to this guy in a chop shop, John Leguizamo, and punches him in the face. Then the gangster’s father calls John Leguizamo and he goes, “I understand you struck my son.”

“Oh, yes, I did, sir.” “May I ask why?” “Yes, sir, because he stole John Wick’s car and killed his dog.” The gangster goes, “Oh.” It’s so cool. If you just saw, oh, on paper, you’d be like, “Oh?” He goes, “Oh, we are so screwed.” It’s a pretty great line read. I’m trying to remember the actor’s name. He’s a Swedish actor who unfortunately died way too young. He was in the original Girl with the Dragon Tattoo, the Swedish version, I believe. I think he played the Daniel Craig role.

Drew: Michael Nyqvist.

Craig: Michael Nyqvist. “Oh.” For that alone.

John: Anyway. Absolutely. That’s the reason why John Wick didn’t get its best screenplay nomination which–

Craig: It should have, by the way. Honestly, I do believe, I think it’s a great screenplay. We could talk in a way. That might be a deep dive.

John: Sure.

Craig: Actually, John Wick might be a deep dive. It’s got one of the most Stuart Special Stuart Specials that you will ever see on screen. That’s actually the one flaw, I think. I would love to dive into that because it is a fantastic example of sparse, just fully reduced screenwriting with these moments of beauty in them.

John: One last question here. Eli has a question about improv movies.

Drew: “Movies like Spinal Tap, Best in Show, and Waiting for Guffman always amazed me because they were so funny and so natural, which is something that you can only get from their improv style of comedy. How would one go about, “Writing” or creating an outline for a movie like that? I want enough structure so that it’s not complete chaos, but also enough left open so there’s room for improv.”

Craig: We should get Alec Berg on to talk about that because that was so much of their process on Curb Your Enthusiasm.

John: Yes. Curb Your Enthusiasm, I know they had detailed outlines and talked through like, “This is what the scene is. This is what happens in the scene,” but then created a structure for the performers to do things. When we had Greta Gerwig on the show, she was talking about the mumblecore movement and how frustrated she got is that without a plan for what was happening in the scene, things just stalled out. Dramatically, it was hard to get things moving. It’s like, “Oh, but it’s comedy. It’s funny.” Is it actually serving the story? Are we moving the ball down the field?

Craig: Yes. I’m paying to watch this.

John: Yes.

Craig: Can you stop just– I’m not paying to see you figure out what the scene should be and then getting there. I’m paying to watch something that feels complete and intentional.

John: Eli, until we get more thorough information and you’re looking at doing this thing, I would say, approach this as you’re writing a movie and approach this as these are the scenes, this is the sequence, this is the build, so you don’t have maybe dialogue for what’s happening in those scenes, but I think you still have the scenes. I think you have the log lines of what’s happening in each of these moments and what the beats are, what you think the in is and what you think the out is.

Craig: Probably some individual lines that you know you need. You create lots of poles and in between people are streaming their own lights. I wonder if we can get Berg Schaefer Mandel to share with us one of the outlines from an episode of Curb just so we could compare and go, “Oh, look, here’s where the gaps were. Here’s how they filled things.” Or, “Actually, here’s how complete the scene was. Just feel like it was more improv than it was.”

John: Absolutely. I think the thing we’ll learn is that you have very talented performers, but you also have people behind the camera who can react, respond, and reshape to get the next thing happening. When we have people on here who’ve talked about multi-cam sitcoms, the reason why those writers are on set is because they can react to things and actually find new ways to connect dots there. It’s just that it an ongoing process.

Craig: And editing.

John: Editing. Yes.

Craig: Can you imagine doing one of those things in a oner?

John: Oh, my God.

Craig: Eeuch. [unintelligible 00:55:58]

John: Let’s do our one cool things. My one cool thing is the Alien roleplaying game Sourcebook by Free League.

Craig: I’m checking this out right now so I understand it.

John: I’m just handing it over to you.

Craig: Oh, yes. You were talking about this at D&D?

John: Yes. Is a hefty black book that is the Sourcebook for playing an Alien-based roleplaying game. Alien, like the movie Alien and the whole Alien franchise. This officially licensed 20th Century Fox project. I bought it mostly because I wanted to do a one-shot with some friends to play a cinematic version in the Alien universe.

What I like about it, even if I think I’d never played the game, is that it paints out the world of the Alien franchise, Weyland-Yutani, the governmental structures behind this, and makes it feel, I don’t know, tangible and real. It’s a really well-executed version of this.

Craig: I would totally. You know who would love this? Phil Hay.

John: I’m playing with Phil Hay. Unfortunately, Craig, you’ll be traveling, but next weekend, we’re going to be doing this one-shot.

Craig: Yes. I’m sorry to miss it because Phil has been talking about Twilight 2000 Forever, which is an old-school 1980s war tabletop RPG system. I’m just looking at this page here of potential injuries. They have a D66, John.

John: It’s two D6s. One is the 6 ones.

Craig: It’s crazy. I love it. You roll these to see what injury you just received?

John: Talk us through some.

Craig: Let’s say you roll– Actually, give me a roll.

John: You rolled a 32.

Craig: Crotch hit.

John: Crotch hit.

Craig: Crotch hit. Fatal? No. One point of damage at every roll for mobility and close combat and that it takes one D6 days to heal which, if you’ve been hitting the crotch.

John: Yes.

Craig: Give me one more.

John: We’ll do a 45.

Craig: 45. Bleeding gut. Could be fatal. Time limit, one shift. That’s a rough shift.

John: What I’ll say I appreciate about it is it’s nice to see the newer mechanics being folded into newer role-playing. Mechanics being folded into here. The two D6s, but also you’re rolling multiple dice to do things each time you have a level of stress.

You have to roll an extra stress die, and it increases the odds of things going very wrong. What’s interesting about the Alien universe is, of course, you’re not expected to live that long. Your survivability is not high in these scenarios, so you have to go in playing it with the expectation you may not make it through.

Craig: In Alien, everybody except Sigourney Weaver tends to die, unless you’re Newt. You should expect to die. Dying, by the way, is a big part of these games. I became a fan of dying when I was playing as a player in Dungeon of the Mad Mage. There was something so fun and awesome about it, like saying goodbye to a character, feeling like, hey, you truly don’t know on any given night if you’re going to make it through.

I love that. There’s another player I play with, a guy named George Finn, who’s like the king of dying. He loves dying. It’s to the point where eventually I became a pretty high-level cleric, and I was like, “You’re not dying.” He’s like, “Oh, come on.” I’m like, “No, I’m not letting you die.” He’s like, “Please?” “No. No. Not on my watch.” Anyway, great recommendation. I’m sorry to miss this one.

John: We’ll let you know how it goes.

Craig: The reason I’m missing it is because I’m going to be in Europe on a little promotional tour for The Last of Us. I’m going to be speaking in Madrid. We’re just doing a talk on screenwriting to all the writers there.

John: I’ve spoken to that same group, I think. They are fantastic. You will love it.

Craig: Amazing. Looking forward to that. Then a premiere in London that Sky puts on, because they run all the HBO shows there in the UK. Hoping to see some of our British friends there. I will report back, including Jack Thorne, who’s probably going to punch me in the face for questioning whether or not maybe an edited version of– [crosstalk]

John: He doesn’t make a violent person so far. The gentlest man in the world.

Craig: Tall and gentle, and a genius. He did it again.

John: I feel like Stephen Graham, actually. He feels like a pugilist.

Craig: Stephen Graham will knock you out, no question. Let’s give Stephen Graham credit here, too. I can already hear Jack yelling at me to stop saying that only he did it, because Stephen Graham is amazing. Jack and Stephen have done incredible work together.

My one cool thing and my one not-so-cool thing this week are related to video games that have come out recently.

Cool. Believe it or not, Assassin’s Creed Shadows. Look, is Assassin’s Creed Shadows exactly the same as every Assassin’s Creed before it?

John: Yes.

Craig: Anything in feudal Japan is already better and it is beautiful. The fact that they’re now doing this on these newer generation things, it looks really beautiful.

John: Are you playing on PS5 or [inaudible 01:00:42]

Craig: PS5. It looks gorgeous. It plays beautifully. What can I say? I’m a sucker for Assassin’s Creed. In the end, I like killing people silently from the shadows, and ninjas are the best at it. Shinobi.

Not so cool. I love it still. I’m saying this out of love. MLB: The Show, 2025. Guys. I like the small, small, small little improvements that happen from year to year, but this has been the same game for years now, and they keep making you buy a new game.

The thing that makes me the craziest is the play-by-play announcing just doesn’t change a little bit. I’m playing a guy who plays for the Yankees. Road to the show, it’s my character. He came up through the minors. I cannot tell you how many times I’ve heard the same damn stories from the announcers. If I hear the story about hitting two wrong runs and a guy giving him a free suit one more time, I’m going to lose my mind. Come on, MLB: The Show. You’re the only one.

It’s the only game that has the MLB license. Please, you can do more. You can. You have a whole year. Do more. Just take a year off. Then come back and blow our minds. Anyway, I still love you. I love you every year. It’s part of the problem. One cool thing. One other thing.

John: Assassin’s Creed Shadows and The Show 25.

Craig: Assassin’s Creed Shadows, thumb up, The Show 25, thumb sideways.

John: That is our show for this week. Scriptnotes is produced by Drew Marquardt, edited by Matthew Chilelli. Outro this week is by Nick Moore. If you want an outro, you can send us a link to ask@johnaugust.com. That is also the place where you can send questions like the ones we answered today. You will find the transcripts at johnaugust.com, along with a sign-up for our weekly newsletter called Interesting, which has a link to our website, and lots of links to things about writing.

We have T-shirts and hoodies and drinkware, you’ll find all those at Cotton Bureau. You can find the show notes with links to all the things we talked about today in the email you get each week as a premium subscriber. Thank you to all our premium subscribers. You make it possible for us to do this each and every week. You can sign up to become one at scriptnotes.net, where you get all those back episodes and bonus segments, like the one we’re about to record on phone essentialism. Craig, thanks for a fun show.

Craig: Thank you, John.

[Bonus Segment]

John: Craig, I’m headed on vacation and I’m really attempting to get off grid. I’m going to set up an email thing saying I’m not able to answer emails, contact Drew if it’s essential. I’ll check in with Drew once a day, but I’m essentially going to be on a no-phone situation. That also seems to coincide with a, I don’t know if it’s a really growing movement, but I see a lot of people talking about phone essentialism. I know you got rid of social media apps, but are you doing anything else to limit the degree to which you’re using your phone or trying to make your phone less present?

Craig: Honestly, getting rid of the social media stuff was the thing. That is the toxicity. Is the toxicity doing the spelling bee in The New York Times puzzle site? No.

Is toxicity getting emails? No, because you can get them on your laptop too. Do I get texted a lot? Sure. Am I a slave to texting? No. But I am not engaging in a constant feedback loop with news and commentary and criticism and fighting. That bit of essentialism has transformed my experience with my phone. I get to see if the Yankees won. Hooray. I don’t get sucked into some miserable rage-baity thing on Facebook or X or Insta.

John: I have an app on my phone called OneSec, which anytime I try to open Facebook, this gets in the way and it has a five-second countdown before I can open up Instagram. It does slow me down. It makes it less appealing to open Instagram, which I think has helped to some degree.

For this trip, what I’m thinking about doing is actually I’ll take my phone with me, but have it powered off for if I really need to do something. I have an old iPhone and I’ll just take everything off that iPhone except for like the absolute crazy essential stuff I need.

That will be my camera and everything else that I’m doing just so that I don’t have that temptation to go to it. Then I’ll just pick up my book rather than picking up my phone.

Craig: Sure. When I’m overseas, I find the phone is useful just to help me navigate and also to look up places to go.

John: On this trip, I don’t have to make any of those choices. We’re basically on an itinerary and we have no choices to make.

Craig: At that point, school trip. You’re right. You don’t need a phone. My older kid was asking me about this– What did she call it? It’s this light phone that’s coming out. There’s some new phone that’s coming out that’s basically it ain’t doing any of that stuff at all. It can’t. It’ll do these things. I understand the movement and I think it’s a good thing.

I think it took a little bit longer than I thought it would take. People are starting to understand what this interactivity means for our brains. Feels like we just lived through the Madmen era of cigarette smoking. Now people are like, “These might be bad for us. These might be deadly for us. Maybe we should cut back.”

Remember, cigarette tobacco companies were massive, massive and still are, but not the way they used to be. If there’s one thing that the tech business has told us time and time again, it’s that whoever you think is irreplaceable and immovable and permanent is not.

John: I see people younger than us who are nostalgic for the old flip phones, where it’s just the numbers. Great, if you want to try that, I’m not nostalgic to go back to that.

Craig: No, those were bad.

John: They were bad. It was just tough.

Craig: Those were bad. I’m also not interested in going back to rotary dialing either.

John: Yes, or fax machines.

Craig: Or fax machines, which were the worst. The things that the phone does, that replaced old methods of things, are great. We used to have to send letters to each other or faxes or have long meetings in person. All the things that we can do now, sending each other messages, in class, passing little notes. Upgraded versions of stuff we used to do, great. Entire new class of interactivity, turns out, not great at all. If you can listen to this podcast on your phone, awesome.

John: I’m fully supportive of venues that require you to lock up your phone with the bags and stuff like that. As long as they have a good system for doing it, I’m fine with it. I went to John Mulaney’s show at the Hollywood Bowl, and for the entire Hollywood Bowl, everyone had to put their phones in bags. Somehow they made it work.

Craig: Yes, we do that for, we had our premiere.

John: You’re using zipper bags.

Craig: Yes, it was zipper bags. I actually talked to them about it. It was like, it’s the honor system.

John: It is the honor system.

Craig: Because it takes forever to unzip the bags, but also, while it’s the honor system, there are people with night vision goggles watching the audience to make sure no one’s doing it. Actually, people were cool about it.

John: People were cool about it.

Craig: Yes, they’re cool.

John: You also repeatedly, there were three warnings along the way, including Jeffrey Wright telling you not to do it.

Craig: Jeffrey Wright, once his voice comes on telling you to not screw with your phones during the show, you probably obey.

John: He’s the watcher in the Marvel Universe.

Craig: That voice.

John: That voice.

Craig: By the way, Jeffrey Wright, I will say first of all, love this man, so awesome. Such a great guy. Sometimes people have that voice that they will– They do when they’re doing, that’s his voice. It’s funny sounds like. It’s awesome.

John: Getting back to what you have on your phone, what you don’t have on your phone, the alternative to actually getting a dumb phone or a light phone or a different thing is actually just to take a bunch of the stuff off your phone.

I’m going to put a link in the show notes to an article by a woman who did just that and really stripped everything down to essentials. There’s something really rewarding about that. There’s something nice about it. Just like, “I have this stuff I absolutely need to do, but I’m not being pulled towards this device.”

Craig: That’s right. In the end, the best app that has ever been designed to get yourself away from these things is your own mind. Because no matter what they give you still have to make a mental choice and you have to stick with your mental choice. Because anybody who buys a light phone can just throw it away and get another one that is full featured. Anybody that says, “I’m going to wait five seconds to open Instagram,” can wait the five seconds and then open Instagram.

It comes down to a commitment. I know because I’ve done it. There’s something a little bit weird and scary. Then you realize, why am I scared about not being on social media? I have not been on social media for the vast majority of my life. Social media in its toxicity convinces you that you must be part of it or you are not part of society itself. I have come to understand that I am more a part of society, not on social media, because that isn’t society. That’s just social media. It’s its own thing that convinces you it’s everything. It’s not. Go outside, touch some grass, et cetera.

John: Good advice. Thanks, Craig.

Craig: Thank you, John.

John: Thanks, Drew.

Drew: Thanks.

Links:

- HBO’s The Last of Us Podcast

- Sundance is moving to Boulder, Colorado!

- Changes to the Academy Nicholl Fellowship

- Adolescence | The Studio

- Meryl Streep and Viola Davis in Doubt

- The Alien RPG by Free League

- Assassin’s Creed: Shadows

- The Show 25

- The DIY Dumbphone Method by Casey Johnston

- Get a Scriptnotes T-shirt!

- Check out the Inneresting Newsletter

- Gift a Scriptnotes Subscription or treat yourself to a premium subscription!

- Craig Mazin on Instagram

- John August on Bluesky, Threads, and Instagram

- Outro by Nick Moore (send us yours!)

- Scriptnotes is produced by Drew Marquardt and edited by Matthew Chilelli.

Email us at ask@johnaugust.com

You can download the episode here.The post Scriptnotes, Episode 683: Our Take on Long Takes, Transcript first appeared on John August.

![‘Omukade’ Trailer – Thai Monster Movie Unleashes an Insane Giant Centipede Nightmare! [Exclusive]](https://i0.wp.com/bloody-disgusting.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/image-30.jpg?fit=1713%2C931&ssl=1)

![‘Sally’ Trailer: Acclaimed Sundance Doc About Trailblazing First Woman To Blast Into Space [Ned]](https://cdn.theplaylist.net/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/02065833/unnamed-2025-05-02T065720.586.jpg)

![100K strategy and powering up with the right cards [Week in Review]](https://frequentmiler.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/powering-up-credit-cards-1.jpg?#)