Related Images | “Tendaberry”

Haley Elizabeth Anderson’s Tendaberry is now showing on MUBI.Tendaberry (Haley Elizabeth Anderson, 2024).Tendaberry was named for the Laura Nyro song “New York Tendaberry.” The end titles are timed to the song, but we weren’t able to get the rights in time. Over the last year, I keep trying to find a single point of genesis for the project. It’s fairly impossible because there are many—one thing folds into another, which leads to another. Hide Your Smiling Faces (Daniel Patrick Carbone, 2013).The Flies Collective—originally Matthew Petock, Zachary Shedd, and Daniel Patrick Carbone—made the film Hide Your Smiling Faces (2013), a beautifully subdued story about two brothers who spend a summer coping after a friend’s death. I discovered this film while still living in Texas and was obsessed with it, and with the story of these three college friends making films together. In 2018, I received the Flies grant to make my thesis film, Pillars. Matt, Zach, and I kept in touch after having films at Sundance in 2020. And through the beginning of the pandemic, Matt helped me with grant applications and budget advice (thank you, Matt!). Then, I sent them an outline of South Brooklyn vignettes.The Little Fugitive (Ray Ashley, Morris Engel, and Ruth Orkin, 1953). Photograph by Ruth Orkin.The heart of Tendaberry was born in film school. An early part of my love for Brighton Beach and Coney Island came from a suggestion made by Todd Solondz that I watch the 1953 film The Little Fugitive. Ruth Orkin’s color photos from The Little Fugitive are stunning. Sometimes archival material can start to feel incredibly present. There’s a point when it stops being something that lives in the past, detached from our present experience. I kept these images in my mental back pocket over the course of the film and felt the same way about the 1900s archival footage of Coney Island and Nelson Sullivan’s work—it’s something that exists alongside us, perhaps on another plane, but still close. Photograph by Haley Elizabeth Anderson (2016).The first time I filmed in Ft. Tilden was during the supermoon in November 2016. We have this image on 16mm film somewhere from that night. I was shooting on an expired roll, or I didn’t know how to control exposure back then, which is obvious in this photo. But that small project had a lot to do with Ft. Tilden’s place in the film—the flip side of Coney Island—the quiet, intimate space, while Coney Island is a vast universe that Dakota has to navigate. Left: Paul Reubens and a friend in an undated photograph. Right: Photograph by Haley Elizabeth Anderson.Paul Reubens and Jim Henson: It might not be apparent at all, but there are some very clear influences and intentional references in the film to both. We screened Tendaberry at the Museum of Moving Image, where the Jim Henson exhibition lives. It was the first place I saw Jim Henson’s pre-Muppet short films and understood that his filmmaking had somehow snuck into my subconscious and into my practice. The film’s wavering attention span and any of the multi-format motifs are all echoes of old-school Sesame Street (1969–) and Pee-wee’s Playhouse (1986–90). I’m surprised that only one person so far has asked, “Where does the ‘secret word’ motif come from?” I feel like it’s embarrassingly apparent. I kept this photo of a young Paul Reubens on my phone at different times on the film. He looks like he feels fully himself, almost invincible. I put my own photo booth pictures on Dakota’s wall—with friends, there was always this strong feeling of invincibility. From Private Views (Barbara Crane, 1980–84).Our cinematographer Matt Ballard and I have hundreds of shared images in our text thread. There are several photos from Barbara Crane’s Private Views. These weren’t necessarily references, because over the course of this project I think both Matt and I rejected this idea of “reference.” I was definitely trying to burn down that idea for myself. I only wanted to reference what was real, not cinematic. We weren’t looking to recreate images, we were looking to conjure up feelings and create images that evoked both specific and indefinable emotions. Like sonder. The ethos behind Private Views felt kin. Small gestures, details: a moment that just is because of the time and place in which it’s captured. You get a full picture of a whole universe while focusing on the disjointed fragments. There will never be another moment like it because the conditions that created it are fleeting.Top: From Subway (Bruce Davidson, 1986). Bottom: Tendaberry (Haley Elizabeth Anderson, 2024).Bruce Davidson’s photo of a girl riding a train always reminded me of a Laura Nyro–type figure. She looks like an angel. We were always subconsciously looking for a moment that encapsulated this spirit. I think that’s what drew me to the image of Dakota standing on the trash can. Jean-Yves Escoffier, on Gummo (Harmony Korine, 1997).I found this screenshot from Matt—it’s Jean-Yves Escoffier talking about h

Haley Elizabeth Anderson’s Tendaberry is now showing on MUBI.

Tendaberry (Haley Elizabeth Anderson, 2024).

Tendaberry was named for the Laura Nyro song “New York Tendaberry.” The end titles are timed to the song, but we weren’t able to get the rights in time. Over the last year, I keep trying to find a single point of genesis for the project. It’s fairly impossible because there are many—one thing folds into another, which leads to another.

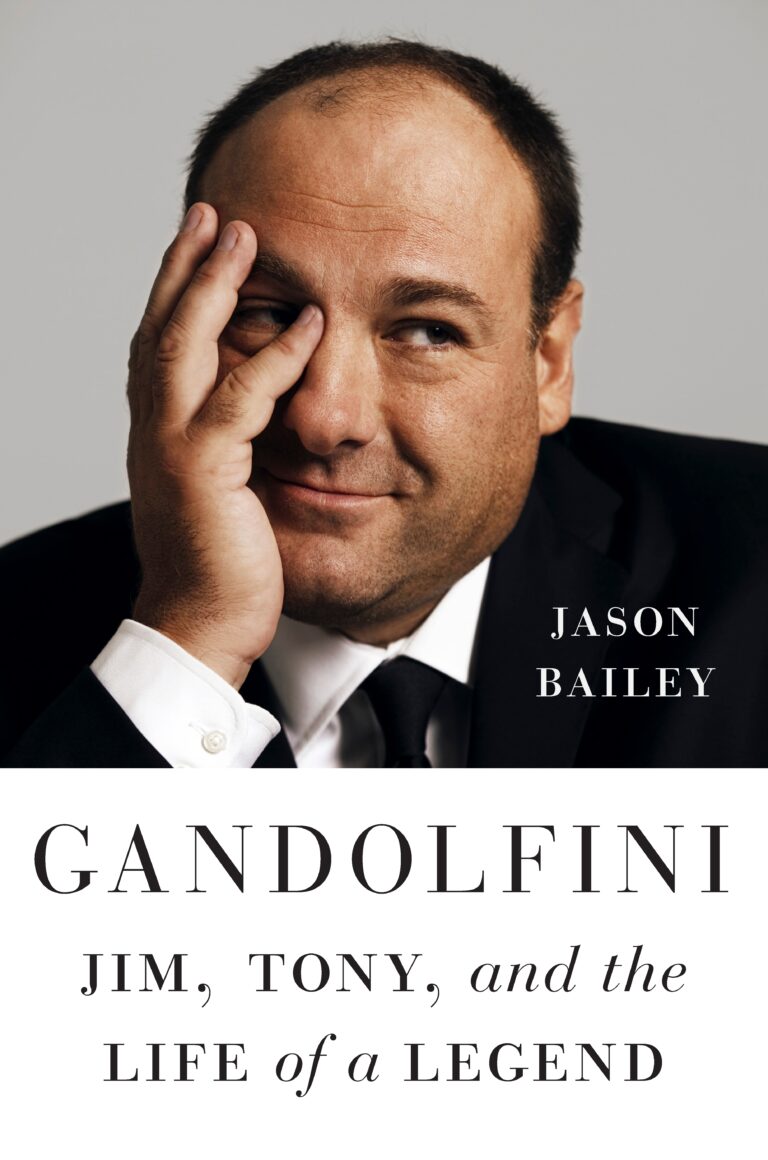

Hide Your Smiling Faces (Daniel Patrick Carbone, 2013).

The Flies Collective—originally Matthew Petock, Zachary Shedd, and Daniel Patrick Carbone—made the film Hide Your Smiling Faces (2013), a beautifully subdued story about two brothers who spend a summer coping after a friend’s death. I discovered this film while still living in Texas and was obsessed with it, and with the story of these three college friends making films together. In 2018, I received the Flies grant to make my thesis film, Pillars. Matt, Zach, and I kept in touch after having films at Sundance in 2020. And through the beginning of the pandemic, Matt helped me with grant applications and budget advice (thank you, Matt!). Then, I sent them an outline of South Brooklyn vignettes.

The Little Fugitive (Ray Ashley, Morris Engel, and Ruth Orkin, 1953). Photograph by Ruth Orkin.

The heart of Tendaberry was born in film school. An early part of my love for Brighton Beach and Coney Island came from a suggestion made by Todd Solondz that I watch the 1953 film The Little Fugitive. Ruth Orkin’s color photos from The Little Fugitive are stunning. Sometimes archival material can start to feel incredibly present. There’s a point when it stops being something that lives in the past, detached from our present experience. I kept these images in my mental back pocket over the course of the film and felt the same way about the 1900s archival footage of Coney Island and Nelson Sullivan’s work—it’s something that exists alongside us, perhaps on another plane, but still close.

Photograph by Haley Elizabeth Anderson (2016).

The first time I filmed in Ft. Tilden was during the supermoon in November 2016. We have this image on 16mm film somewhere from that night. I was shooting on an expired roll, or I didn’t know how to control exposure back then, which is obvious in this photo. But that small project had a lot to do with Ft. Tilden’s place in the film—the flip side of Coney Island—the quiet, intimate space, while Coney Island is a vast universe that Dakota has to navigate.

Left: Paul Reubens and a friend in an undated photograph. Right: Photograph by Haley Elizabeth Anderson.

Paul Reubens and Jim Henson: It might not be apparent at all, but there are some very clear influences and intentional references in the film to both. We screened Tendaberry at the Museum of Moving Image, where the Jim Henson exhibition lives. It was the first place I saw Jim Henson’s pre-Muppet short films and understood that his filmmaking had somehow snuck into my subconscious and into my practice. The film’s wavering attention span and any of the multi-format motifs are all echoes of old-school Sesame Street (1969–) and Pee-wee’s Playhouse (1986–90). I’m surprised that only one person so far has asked, “Where does the ‘secret word’ motif come from?” I feel like it’s embarrassingly apparent. I kept this photo of a young Paul Reubens on my phone at different times on the film. He looks like he feels fully himself, almost invincible. I put my own photo booth pictures on Dakota’s wall—with friends, there was always this strong feeling of invincibility.

From Private Views (Barbara Crane, 1980–84).

Our cinematographer Matt Ballard and I have hundreds of shared images in our text thread. There are several photos from Barbara Crane’s Private Views. These weren’t necessarily references, because over the course of this project I think both Matt and I rejected this idea of “reference.” I was definitely trying to burn down that idea for myself. I only wanted to reference what was real, not cinematic. We weren’t looking to recreate images, we were looking to conjure up feelings and create images that evoked both specific and indefinable emotions. Like sonder. The ethos behind Private Views felt kin. Small gestures, details: a moment that just is because of the time and place in which it’s captured. You get a full picture of a whole universe while focusing on the disjointed fragments. There will never be another moment like it because the conditions that created it are fleeting.

Top: From Subway (Bruce Davidson, 1986). Bottom: Tendaberry (Haley Elizabeth Anderson, 2024).

Bruce Davidson’s photo of a girl riding a train always reminded me of a Laura Nyro–type figure. She looks like an angel. We were always subconsciously looking for a moment that encapsulated this spirit. I think that’s what drew me to the image of Dakota standing on the trash can.

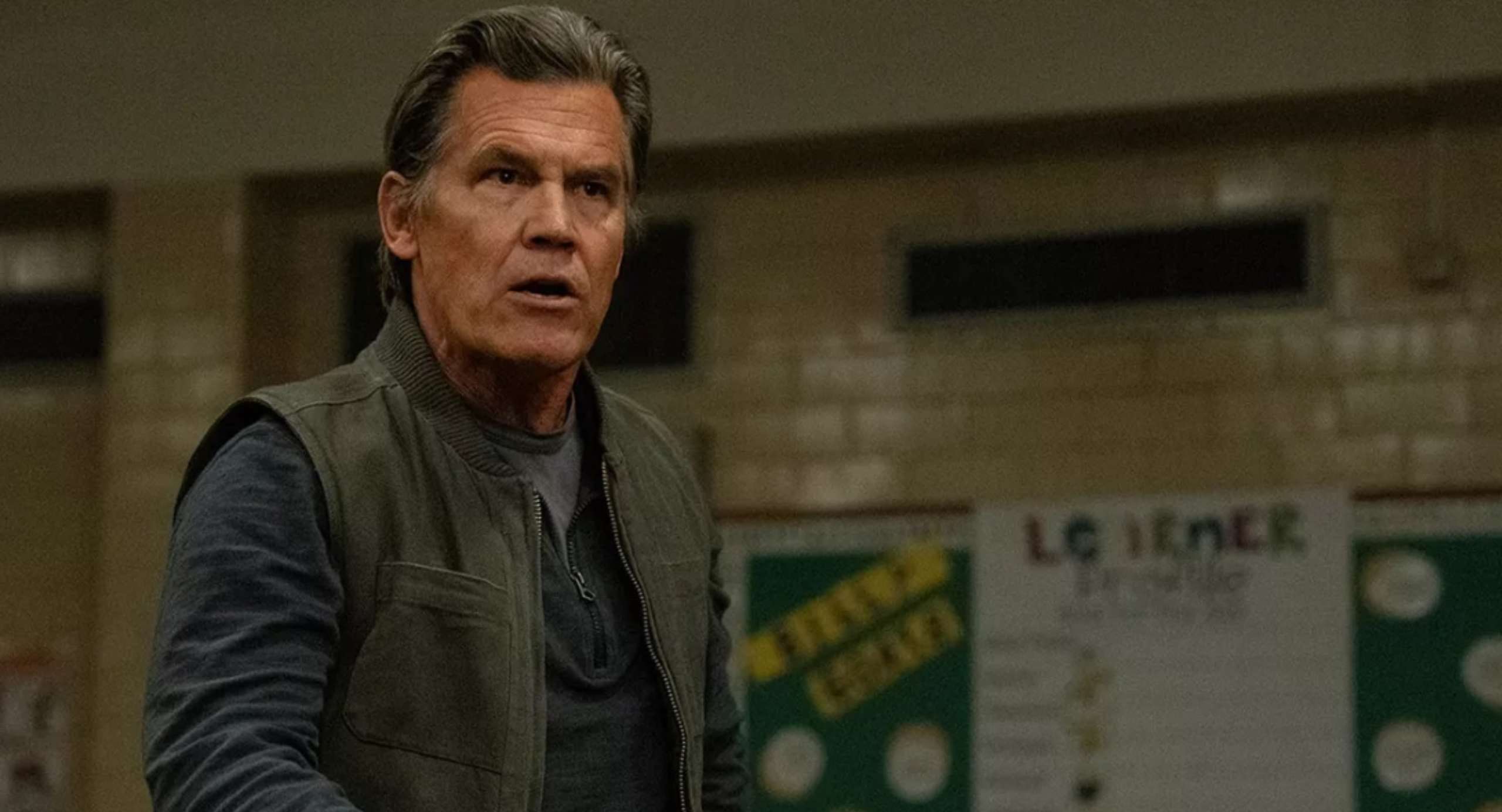

Jean-Yves Escoffier, on Gummo (Harmony Korine, 1997).

I found this screenshot from Matt—it’s Jean-Yves Escoffier talking about his experience on Gummo (1997). I do think Matt really embodied this idea and I think we all began to feel this way: “To establish a feeling that something might happen, to be ready for it and organize everything around you, so nobody can mess things up.” Carlos Zozaya and Camila Morales—producers, assistant directors, sanity keepers—protected this idea throughout the summer chapter. I feel the most joy when filming in the midst of something that is real, happening in real time all around.

From Coney Island Kaleidoscope (Lynn H. Butler, 1999).

Some of the earliest images that I shared with everyone were those from a book called Coney Island Kaleidoscope by Lynn H. Butler, specifically this untitled image—it felt euphoric, impressionistic. It was related to dance and joy rooted in a place.

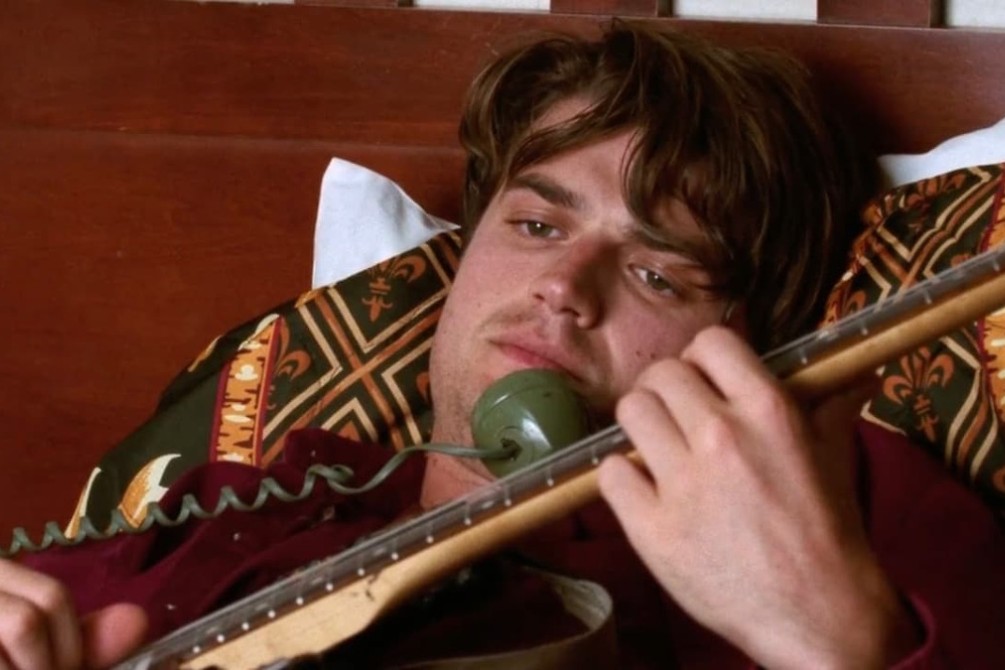

Summer with Monika (Ingmar Bergman, 1953).

Summer with Monika (1953). The images of Monika, her body language, her defiant stance. She’s not always the most sympathetic of characters—but I love how she, and her relationship, transforms: from being in love to becoming a type of feral child that is forced to grow up and return to the real world. When she returns, the couple has changed—one person more in love with the other, and nothing can continue in the same way. It’s a heartbreaking ode to being young and dumb and in love. This is one of the first films I told Dakota to watch. The image of a defiant girl facing the sun was always a North Star for Dakota’s character.

Rosetta (Luc and Jean-Pierre Dardenne, 1999).

Rosetta (1999), the film and the character, was likewise a constant North Star—tonally and rhythmically. Émilie Dequenne—her face, her gaze, her ferocity—is the entire film.

Spinning Christmas Tree, New York City (Joel Meyerowitz, 1977).

Joel Meyerowitz’s Spinning Christmas Tree: maybe this was one of a very few reference photos—an unrealized image from the film. The apartment foyer I was living in at the time was almost identical to the one in the photo. I bought the tree and the spinning base. It’s still in storage somewhere.

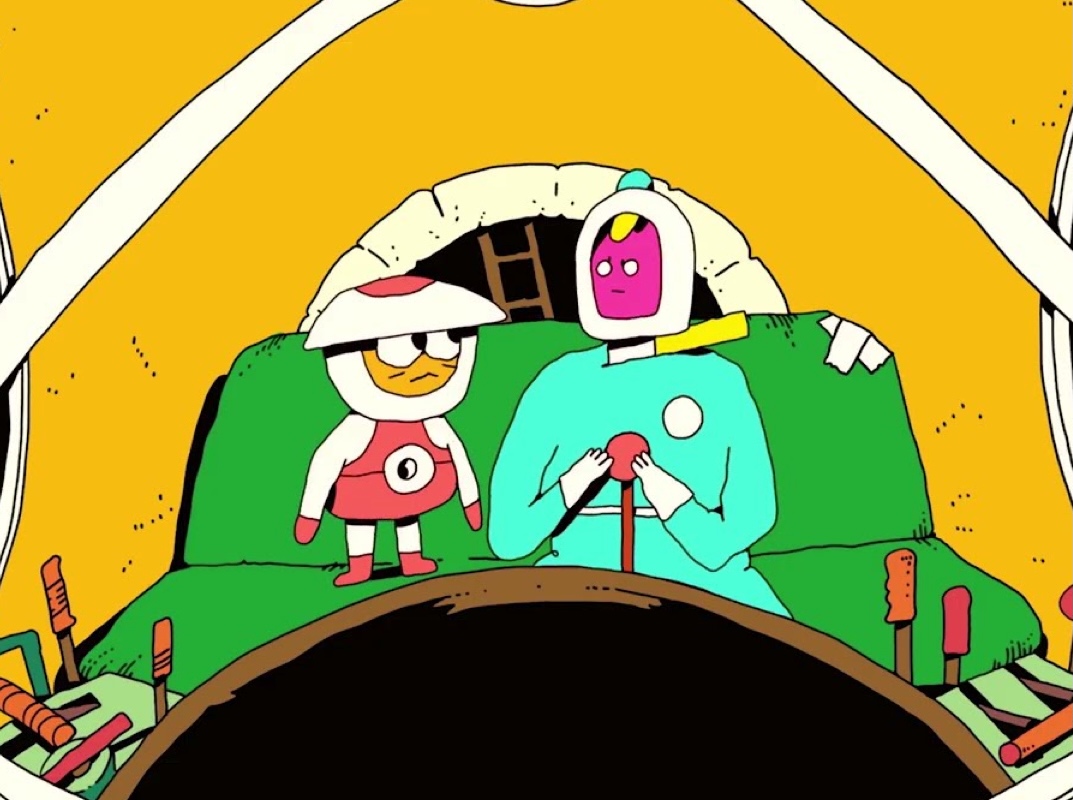

Gang (Clayton Vomero, 2015).

Clayton Vomero’s Gang. In film school, there were those short films, music videos, and art installations that lived on private links passed between two or three of us at a time. Frank Ocean’s “Nikes” was on repeat. This film lived on Dazed for a while and then disappeared out of the blue. There was something very “film school” about it, which to me isn’t a negative. It feels like what I thought my life felt like at the time. Imperfect, messy, but somehow joyous. I wanted a little of that to live in this film, maybe a lot of it—the city, your friends, a camera, and no plans. A text thread full of Frank Ocean references and Stuart Winecoff photos—so 2016.

Left: Untitled #1414, from Nakazora (Masao Yamamoto, c. 2001). Right: Tendaberry (Haley Elizabeth Anderson, 2024).

Masao Yamamoto: Matt shared this photo with me as we were beginning to conceptualize the shift from spring to summer. He always told me he imagined this image of Dakota suspended in the darkness. I think I mentioned a fish being washed up on shore or something silly like that. But this image led to the moment of Dakota on the bed in the film’s third interlude—an image of both death and rebirth.

I always run the risk of getting too emotional when speaking about people who live inside the fabric of this film. The film is dedicated to three people—Tom Richmond, Stephen Gerald, and Hash Halper. Stephen Gerald was my mentor in the UT Austin theater department, who told me I needed to get out of Texas and run to New York. Writing about Stephen would take up several pages.

Little Odessa (James Gray, 1994).

I met Tom Richmond at NYU—he taught cinematography, of course. Tom used to live in Texas and we connected over punk music at the end of class one day. He got me into the band X. With a sly wink, he let me “borrow” a Super 8 camera hidden in a first floor soundstage locker (it wasn’t his, and I wasn’t supposed to keep it). Tom shot James Gray’s first film, Little Odessa (1994), in Brighton Beach—we feature most of the same locations he captured back then. I put on Little Odessa without sound several times over the course of making Tendaberry, watching the flow of the images. I held Tom extra close in my thoughts over those three years. I will always be grateful that we shared a hug on Bedford Avenue before he passed.

Hash Halper and his heart graffiti followed me around East Village during some dark days. I only knew him as the guy who drew hearts, like most others. But, I ran into his “cheer up” spirit at the right time. Honestly, I hope that the last part of the film helps someone like Hash’s little chalk hearts helped me in Tompkins Square Park in 2019. RIP to Tom, Stephen, and Hash.

Photographs by Haley Elizabeth Anderson.

Space: at the very beginning of this journey, Matt and I discovered that we shared a friend. He showed me a picture of a guy sitting in the middle of his living room, and I recognized him instantly. It was this friend’s apartment that we filmed in. Anthony’s apartment is a story in itself: the way he keeps objects and arranges pictures, how he sticks incense in the little cracks in the wall. The scent. The sound of the street coming in through the windows. Kota and I talk about the spirit of this space often. We intended the apartment in the film to feel like a character.

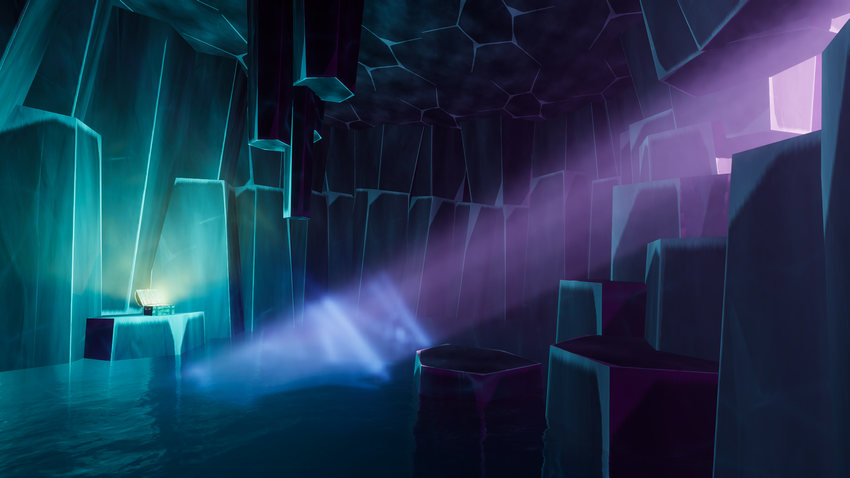

The Lovers on the Bridge (Leos Carax, 1991).

The Lovers on the Bridge: Matt and I spoke about the look of this film several times over the third and fourth chapters. I don’t remember all of our conversations—maybe it had something to do with lens choice, composition, color. It’s one of the most striking films I’ve ever seen and one of my favorites. It wasn’t until making Tendaberry that I reread about how troubled the production was, building a replica of a bridge in the middle of Paris... wildly ambitious.

Photograph by Laura Wilson.

I’m not the only one saying this, but making an indie film feels like swimming upstream. Sometimes like drowning. And it’s difficult to think about creating at all sometimes because everything feels bleak. Now that Tendaberry is being released out into the world, I spend a lot of time talking about what’s next. You know, hopes and dreams: there’s this photo of Wes Anderson and Owen Wilson skipping out of an office together because they closed a deal to make a movie.

Photograph by Haley Elizabeth Anderson.

A man eating his watermelon like an NYC boss: with his Metro Card.

Photograph by Haley Elizabeth Anderson.

Camilla holding up Matt trying to hold the shot together on the Q train. My favorite photo of the entire production.

![‘Project MKHEXE’ Clip Uncovers a Mysterious Treehouse [Exclusive]](https://bloody-disgusting.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/MKHEXE_still.jpg)

![Kyoto Hotel Refuses To Check In Israeli Tourist Without ‘War Crimes Declaration’ [Roundup]](https://viewfromthewing.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/war-crimes-declaration.jpeg?#)

.png?width=1920&height=1920&fit=bounds&quality=70&format=jpg&auto=webp#)

.jpg?#)