Ticked Off: Against “The Clock”

Illustrations by Liv Garber.In the dark of a cinema, the audience is invited to forget about everything except the image on screen. At an art museum, however, the original intent of an artist is subject to contamination by a variety of other authors—the architect, the curator, exhibition designers, and any additional artists whose work may be encountered during one’s visit. On top of these invisible authors, there are security guards, tour guides, and other viewers with their unpredictable movements, pacing, and commentary. And so, from the moment the Museum of Modern Art announced it would only offer two overnight showings of Christian Marclay’s day-long film The Clock (2010), for which members would receive priority ticketing, I knew I was in for an irritating time.The Clock is a 24-hour montage made up of thousands of film and television excerpts featuring clocks and various allusions to time. As MoMA’s exhibition text notes, “James Bond checks his watch at 12:20 a.m.; Meryl Streep turns off an alarm clock at 6:30 a.m.; a pocket watch ticks at 11:53 a.m. as the Titanic departs.” For each installation, The Clock is synchronized with the local time. When the film premiered at White Cube in London in 2010, the exhibition was open 24 hours a day for its entire run and attracted thousands of visitors per week. Within months, five editions of the work sold for half a million dollars each to various institutions, and a sixth to hedge-fund manager Steve Cohen, who paid an undisclosed amount (and apparently displays it on a dedicated monitor in his office). Paula Cooper Gallery in New York mounted a continuous 24-hour exhibition in early 2011, and later that year Marclay won the Best Artist award at the Venice Biennale. Since then, dozens of the world’s major art institutions have presented the work, often with significant compromises—at MoMA, it is accessible only during regular museum hours, save for a few special events, rendering well over half of the work invisible.I arrived at 7 p.m., passing a few dozen hopefuls who had failed to reserve tickets lined up outside in below-freezing temperatures. Inside, I was told there would be a wait to enter the screening room, which was already at capacity. This purgatory turned out to be highly rewarding, as I was able to wander around the collection galleries on the second floor and contemplate the work of Richard Serra and Montien Boonma in solitude, a realization of childhood fantasies of finding myself alone in malls and museums at night.After two hours, I received a text notification that it was my turn to enter the exhibition. There was no seating available on the grid of white IKEA couches glowing beneath the projection of The Clock. Arranged into rows and columns, as specified by Marclay, there was space not just in front of each couch but also along each side. In an art world fueled by artificial scarcity—the logic that demands an infinitely reproducible video file be limited to an edition of six—this waste of space was entirely appropriate. An usher guided me to the rear of the room and motioned toward an open space between other viewers leaning against the wall. When I removed my coat and sat on the floor, she immediately returned to tell me I had to remain standing. At least once every few minutes, someone new would enter the room, try to sit on the floor, and be reprimanded by a security guard. I watched the couches for a while, thinking someone might rise, but gradually realized everyone who landed a seat was probably staying until The Clock struck midnight, which is thought of as a punctuation mark for the work. Installation view of The Clock (Christian Marclay, 2010) at White Cube Mason’s Yard, London. Photograph by Todd-White Photography. Courtesy of Paula Cooper Gallery and White Cube.Eventually, I accepted my likely fate—that I would remain standing for at least three hours—and settled into The Clock. I was first struck by how unfortunate it was that Marclay and his team undertook the project in 2007. Had they waited just a few years, they could have been ripping Blu-rays or rapidly downloading high-definition files and avoided the lossy standard-definition compression that defaces every frame of the film. This would have also allowed Marclay and his team to draw from a much broader archive than that afforded by DVDs rented from London video stores and purchased off of eBay. Had they waited a few years more, they could have automated their search for clocks and dialogue that marks time through audio- and image-analysis software such as Faster R-CNN or ImageJ. More options would have afforded more choice in terms of edits and a more expansive work overall, though I doubt that Marclay's montage approach would be much more interesting even if he was working from a larger set. While The Clock is a carefully constructed piece for which Marclay adopted the conventions of classical editing to compose his scenes—with continuity of sound, eye line, and telepho

Illustrations by Liv Garber.

In the dark of a cinema, the audience is invited to forget about everything except the image on screen. At an art museum, however, the original intent of an artist is subject to contamination by a variety of other authors—the architect, the curator, exhibition designers, and any additional artists whose work may be encountered during one’s visit. On top of these invisible authors, there are security guards, tour guides, and other viewers with their unpredictable movements, pacing, and commentary. And so, from the moment the Museum of Modern Art announced it would only offer two overnight showings of Christian Marclay’s day-long film The Clock (2010), for which members would receive priority ticketing, I knew I was in for an irritating time.

The Clock is a 24-hour montage made up of thousands of film and television excerpts featuring clocks and various allusions to time. As MoMA’s exhibition text notes, “James Bond checks his watch at 12:20 a.m.; Meryl Streep turns off an alarm clock at 6:30 a.m.; a pocket watch ticks at 11:53 a.m. as the Titanic departs.” For each installation, The Clock is synchronized with the local time. When the film premiered at White Cube in London in 2010, the exhibition was open 24 hours a day for its entire run and attracted thousands of visitors per week. Within months, five editions of the work sold for half a million dollars each to various institutions, and a sixth to hedge-fund manager Steve Cohen, who paid an undisclosed amount (and apparently displays it on a dedicated monitor in his office). Paula Cooper Gallery in New York mounted a continuous 24-hour exhibition in early 2011, and later that year Marclay won the Best Artist award at the Venice Biennale. Since then, dozens of the world’s major art institutions have presented the work, often with significant compromises—at MoMA, it is accessible only during regular museum hours, save for a few special events, rendering well over half of the work invisible.

I arrived at 7 p.m., passing a few dozen hopefuls who had failed to reserve tickets lined up outside in below-freezing temperatures. Inside, I was told there would be a wait to enter the screening room, which was already at capacity. This purgatory turned out to be highly rewarding, as I was able to wander around the collection galleries on the second floor and contemplate the work of Richard Serra and Montien Boonma in solitude, a realization of childhood fantasies of finding myself alone in malls and museums at night.

After two hours, I received a text notification that it was my turn to enter the exhibition. There was no seating available on the grid of white IKEA couches glowing beneath the projection of The Clock. Arranged into rows and columns, as specified by Marclay, there was space not just in front of each couch but also along each side. In an art world fueled by artificial scarcity—the logic that demands an infinitely reproducible video file be limited to an edition of six—this waste of space was entirely appropriate.

An usher guided me to the rear of the room and motioned toward an open space between other viewers leaning against the wall. When I removed my coat and sat on the floor, she immediately returned to tell me I had to remain standing. At least once every few minutes, someone new would enter the room, try to sit on the floor, and be reprimanded by a security guard. I watched the couches for a while, thinking someone might rise, but gradually realized everyone who landed a seat was probably staying until The Clock struck midnight, which is thought of as a punctuation mark for the work.

Installation view of The Clock (Christian Marclay, 2010) at White Cube Mason’s Yard, London. Photograph by Todd-White Photography. Courtesy of Paula Cooper Gallery and White Cube.

Eventually, I accepted my likely fate—that I would remain standing for at least three hours—and settled into The Clock. I was first struck by how unfortunate it was that Marclay and his team undertook the project in 2007. Had they waited just a few years, they could have been ripping Blu-rays or rapidly downloading high-definition files and avoided the lossy standard-definition compression that defaces every frame of the film. This would have also allowed Marclay and his team to draw from a much broader archive than that afforded by DVDs rented from London video stores and purchased off of eBay.

Had they waited a few years more, they could have automated their search for clocks and dialogue that marks time through audio- and image-analysis software such as Faster R-CNN or ImageJ. More options would have afforded more choice in terms of edits and a more expansive work overall, though I doubt that Marclay's montage approach would be much more interesting even if he was working from a larger set.

While The Clock is a carefully constructed piece for which Marclay adopted the conventions of classical editing to compose his scenes—with continuity of sound, eye line, and telephone dialogue repeatedly bridging unrelated films—one starts to understand what Marclay means when he says he “knows nothing about cinema.”

His editing on the one hand gestures toward mood—at 10 p.m., a sequence of women drinking alone indicates sadness; in the afternoon, a sequence of people rushing to appointments indicates anxiety. But these moods are merely demonstrated, as their cinematic potential is broken through disjunctive forms—this high concept ’80s blockbuster to that Classical Hollywood film, this science fiction world to that neorealist world, color to black-and-white, contemporary to period. Marclay explains this away as if the work offers some kind of educational utility for an alien species that has never experienced visual storytelling: “You become aware of how film is constructed—of these devices and tropes they constantly use. Like, if someone turns abruptly, you expect someone else to be in the next cut. An actor looks down at his watch and, suddenly, you have a closeup of the watch. But, if the first clip is in black-and-white and the next is in color, you know you’ve been fooled.”

On the other hand, he’s using behavioral patterns as a guardrail, emphasizing that, as in real life, certain actions are tied to particular times of day in television and cinema. People leave work around five. Calls in the middle of the night are often bad news. The confirmation of such patterns yields a reading about as complex as that’s life.

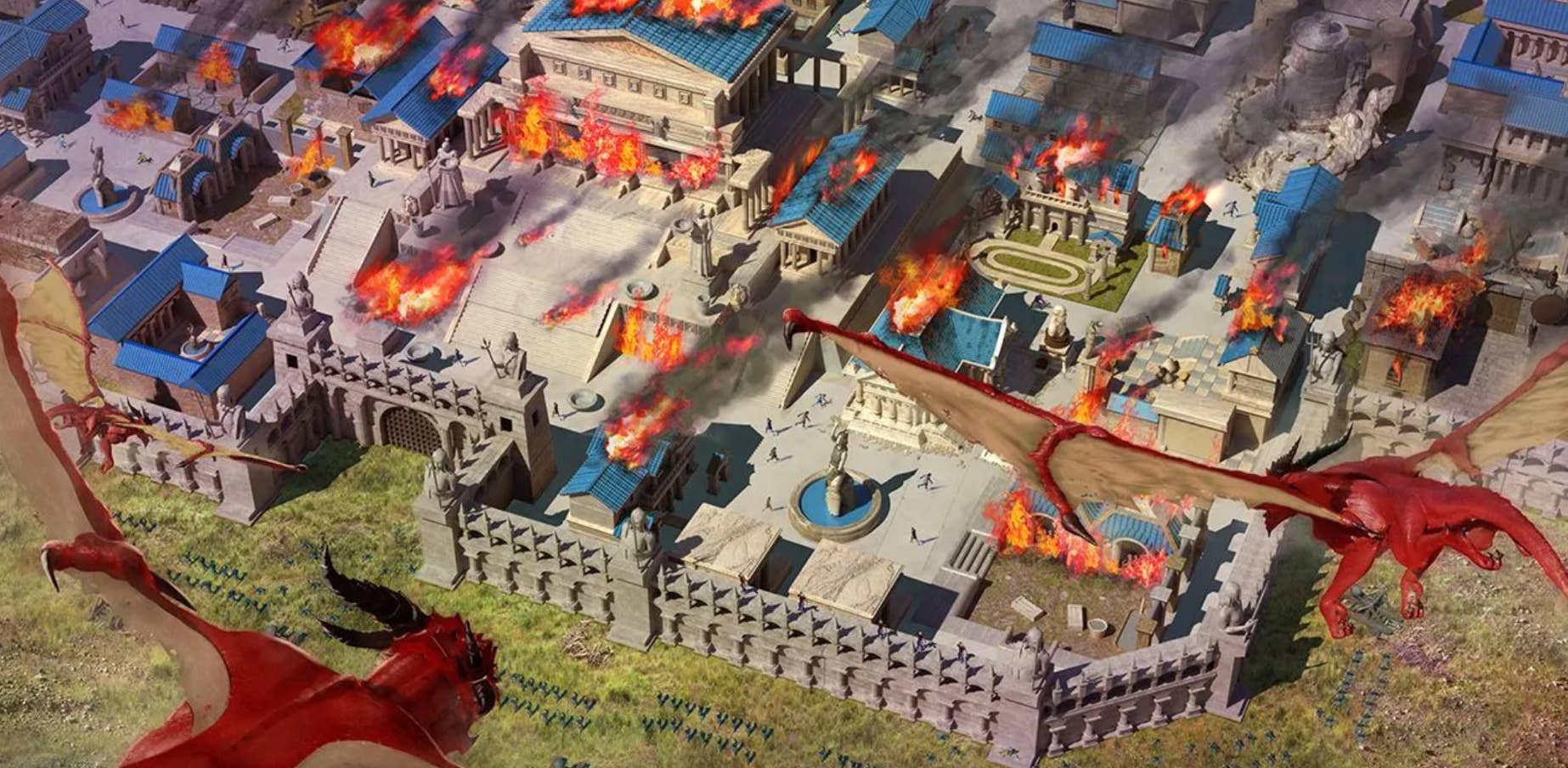

The Clock (Christian Marclay, 2010).

The overall conceit of the work—it's a clock—is the kind of smart-dumb conceptual-art premise that seems to serve hand-waving curators best. “The Clock collapses the fictional time presented on screen with the actual time of each passing minute,” they’ll say, though it’s actually a bit more complicated than that, as viewers don’t get to experience the building blocks of “fictional time”—pacing, duration, character arcs, and so on. In The Clock, Marclay merely presents fragments in which measured time is explicitly marked. Stripped of their narrative contexts, the clips figure more as cultural objects than habitable fictional worlds.

“Rather than entering a time zone different from one’s own and, as it were, losing oneself there—one of the pleasures of time-based art—The Clock made viewers hyperaware of their subjective sense of time,” writes Amy Taubin. Yet ever since this work was made, I’ve arrived at a cinema at a particular hour with a precise knowledge of the film’s duration and a time-telling device in my pocket.

Given the ways in which our phones have atomized the creation of moving-image content, the mass cooperation that filmmaking requires has become even more difficult to fathom. So has getting out of the house for a communal viewing experience. When Marclay commenced full-scale production on The Clock in 2007—the same year the iPhone was introduced and Netflix launched its streaming service—approximately 1.4 billion movie tickets were sold in American theaters; in 2024, that number was only 760 million.

Still, thousands of films are currently in production around the world. On any given set, while the assistant director is busy talking to the director about how much time they have to accomplish the next block of fiction, there are a bunch of other crew members working against the clock to complete their tasks at hand, or waiting—most likely idling on their phones. Everyone involved is having their own separate experience working to prepare a particular shared fiction. Then, when action is called, they all synchronize to execute that fiction, and it comes to life before them.

The claim that “Marclay spent three years meticulously editing The Clock” is less impressive when considered alongside the immense amount of thought, labor, and cooperation that goes into any crew-based feature film, their labor expenditure eclipsing that of The Clock in ways that are hard to quantify because every film is an expansive collective endeavor. Even “bad” movies are impressive achievements—ridiculous arrangements of behavior all in pursuit of a fantasy. When everything aligns and enables our favorite movies to emerge, they feel like miracles and constitute some of the greatest art ever achieved by humanity.

The Clock (Christian Marclay, 2010).

The Clock encapsulates “100 years of moving-image history.” Which histories, though? Despite the thoroughly globalized film culture within which Marclay and his team worked, The Clock still skews heavily toward Hollywood cinema and the European arthouse.

The work emerged at a time when appropriation films were starting to lose their potency due to the proliferation of supercuts and mashups online. The obsessive process Marclay embarked on in 2007 has now become run-of-the-mill. YouTube hosts countless channels full of reedited clips from cinema history, some serving artistic ends, but with many others geared toward educating enthusiasts. The individuals who compose these edits often choose to remain anonymous. Few, if any, hold the pretension of eclipsing the authorship of the filmmakers they’re borrowing from.

Much of the work that precedes this explosion over the past two decades—the films of Bruce Conner and Dara Birnbaum, for instance—is interesting in art historical terms, but now that we have teenagers pumping out edits with far greater breadth and nuance for TikTok, these gestures of appropriation often feel crude and flaccid. Appropriation has become second nature; making a film about appropriation now is kind of like saying your drawing is about using a pencil. The work’s grand gesture appears less as a revelation or profound insight, and more as a symptom of artists' access to film history and nonlinear editing technologies.

The Clock (Christian Marclay, 2010).

While Marclay was toiling over The Clock, other artists responded more nimbly to the emerging possibilities for appropriation. In the minute-long A Policeman Is Walking (2009), Stephen Sutcliffe repurposed an early screensaver that calls to mind hard-edge abstract painting as it gesticulates along to the audio of a spoken poem. Sturtevant’s nine second Finite Infinite (2010) is a single shot of a black dog running across a field with unsure footing, from left to right, set to a clamoring, rhythmic soundtrack. Such works estrange their footage, not belaboring the question of who made their images. What matters is the shape of the experience the artist has cultivated for the viewer.

An awareness of appropriation’s shifting registers after the advent of YouTube is baked into my own works that lift footage from elsewhere. For In the Air Tonight (2020), I chose clips that didn't show faces because recognizable actors would immediately refer to films outside of my own and rupture the mood I hoped to create. I tried my best to make all the clips I used look like they came from the same film by unifying their textures and color palettes. I cropped everything to a 4:3 ratio to maintain uniformity and so I could edit spatially within the frame. By this process, a relatively seamless new narrative could emerge out of disparate fragments.

There are many methods by which one might handle borrowed footage, of course, and Marclay’s convoluted endeavor is laced with conceptual, emotional, existential, and taxonomical aspirations beyond the simple fact of appropriation. Still, I found myself thinking about the sources of his clips more often than I wished, turning it into a game of name-the-film. While this process of identification isn’t all that generative as a response to an artwork, it points to what’s most interesting about The Clock—that which lies beyond its edges: not only the films Marclay borrowed from, but every other film not included.

As pain began to radiate up my legs from leaning forward and craning my neck to see the screen, I tried to distract myself by imagining every film used in The Clock playing simultaneously on screens around the world. From there, I was confronted with the sublime immensity of all the films ever made, flickering in cinemas, electronics stores, living rooms, and the palms of countless hands. The thought of these countless fictions running parallel to one another led me to wonder: What was everyone else in the world doing at that exact moment? Faced with the multitude of human experience, unified only by the inescapable rhythm of time, I ached for experiences that seemed impossible within this dark room. I was consumed by an overwhelming dread that, like Marclay in 2007, I had chosen to waste my time at the wrong time. The pain in my legs was too great. I left the gallery and looked at my phone. It was 11:32 p.m. I called a friend and made a plan to catch a matinee the following day.

![‘Ready or Not 2’ Cast Announce Includes Sarah Michelle Gellar and David Cronenberg! [Video]](https://bloody-disgusting.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/ready-or-not-movie-1024x591.png)

.png?format=1500w#)

.png?format=1500w#)

![Mouse Invades United Club at LaGuardia on the Eve of $1,400 Fee Hike [Roundup]](https://viewfromthewing.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/united-club-lga.jpg?#)

![Caught on Video: “He Busted Through!” Frontier Airlines Passenger Storms Closed Las Vegas Gate [Roundup]](https://viewfromthewing.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/Screenshot-2025-04-20-140707.png?#)

![It’s Unfair to Pay 100% for 50% of a Seat—Why Airlines Must Start Refunding Customers When They Fail To Deliver [Roundup]](https://viewfromthewing.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/broken-american-airlines-seat.jpeg?#)

.jpg?#)

.jpg?#)

![[Podcast] Unlocking Innovation: How Play & Creativity Drive Success with Melissa Dinwiddie](https://justcreative.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/melissa-dinwiddie-youtube.png)