Scriptnotes, Episode 682: The Second Season with Tony Gilroy, Transcript

The original post for this episode can be found here. John August: Hey, this is John. A standard warning for people who are in the car with their kids. There’s some swearing in this episode. [music] John: Hello and welcome. My name is John August. Craig Mazin: My name is Craig Mazin. John: You’re listening […] The post Scriptnotes, Episode 682: The Second Season with Tony Gilroy, Transcript first appeared on John August.

The original post for this episode can be found here.

John August: Hey, this is John. A standard warning for people who are in the car with their kids. There’s some swearing in this episode.

[music]

John: Hello and welcome. My name is John August.

Craig Mazin: My name is Craig Mazin.

John: You’re listening to Scriptnotes. It’s a podcast about screenwriting and things that are interesting to screenwriters.

Today on the show, how do you approach the second season of the acclaimed TV show you created? It’s a question asked by roughly 1% of our listening audience, and yet the answer is surprisingly relevant to anyone dealing with the pressures of expectation and reality.

Craig: It’s relevant to 66% of the people right now on this podcast.

John: Which is so odd to have you both here. We will also answer listener questions about transitioning from journalism to screenwriting and what to do when you realize that someone else is making something with the same premise.

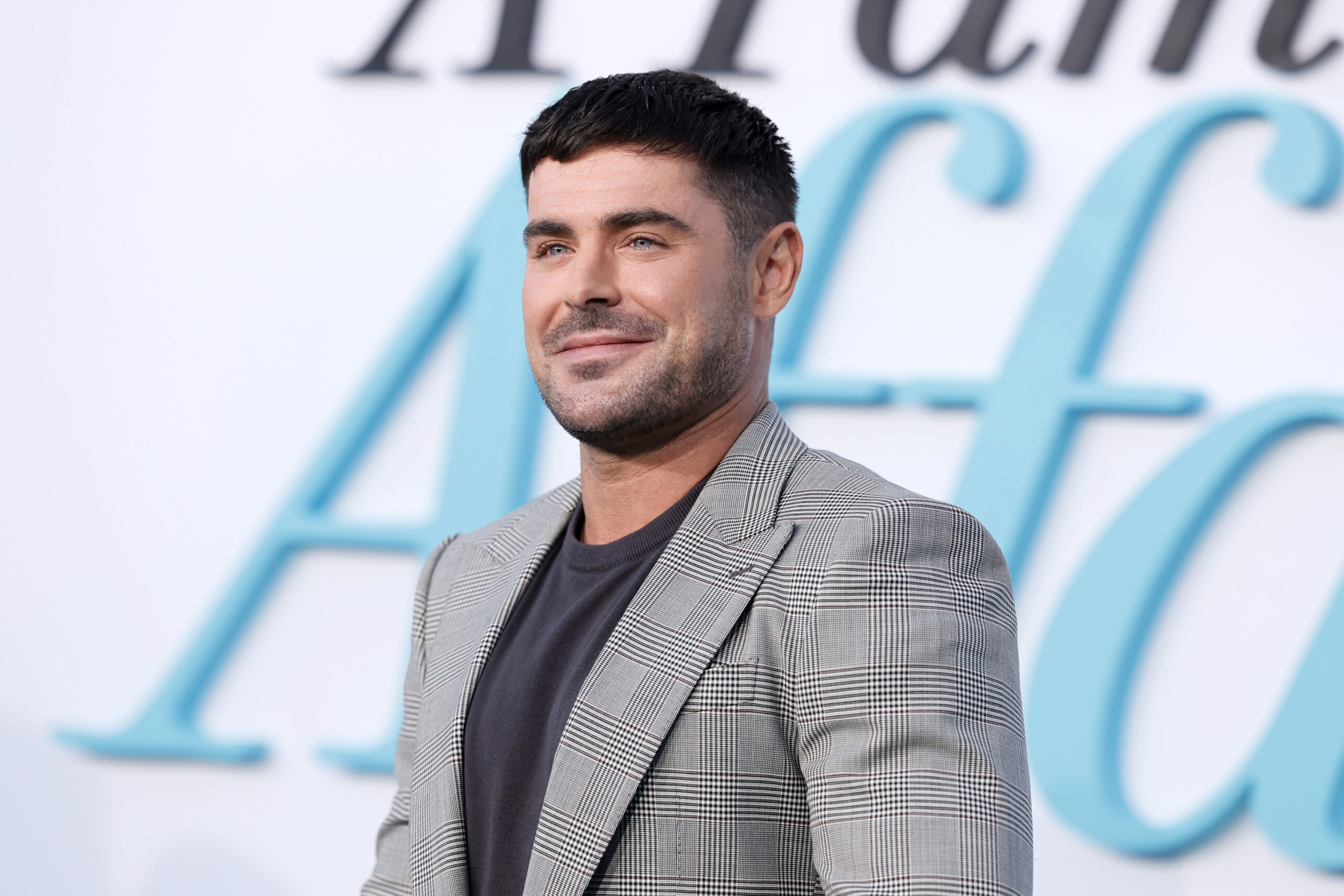

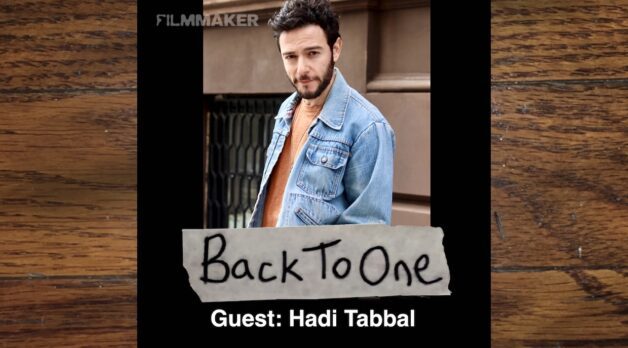

To help us do all this, we have a very special guest. Tony Gilroy is the writer and director of movies such as Michael Clayton, Duplicity, The Bourne Legacy. He also wrote The Bourne Identity, Bourne Supremacy, Bourne Ultimatum, Devil’s Advocate, Rogue One, and, of course, The Cutting Edge with D.B. Sweeney. Most relevant to today’s episode, Tony is also the creator and showrunner of Andor, which starts its second season on April 22nd. Welcome to Scriptnotes, Tony Gilroy.

Tony Gilroy: It is a pleasure to be here. It really is. I’ve been listening, so it’s nice to be someplace where you’ve visited.

Craig: That is startling and disturbing. Well, it’s very flattering. Tony Gilroy, for those of you who follow screenwriting, needs no introduction even though John gave him one. If you’re a casual listener, let me explain. We’ve got one of the all-time great first-ballot hall of famers here with us today.

John: Weirdly, Tony, your name has come up so much recently on the show because after our Moneyball episode with Taffy Brodesser-Akner, she mentioned running into you, which was great. Then a couple of weeks ago, Christina Hodson was on. We were talking through action sequences. We went through a great action sequence of yours from The Bourne Identity, which was so much fun to see and to see how you were doing things on the page, which is different than how Craig or I or other folks would do things on the page. It’s great to have you. You’ve been on our mind, so to have you on our show is just a delight.

Tony: I listened to that episode yesterday to prep for today. I thought she did an amazing– she just covered all of it. It was very well-played. It’s very instructive. That episode was really terrific.

John: Yes, so Craig will never listen to that episode. Craig, Christina was really smart.

Craig: I will. You don’t know that.

Tony: You have a lot to learn. There’s things to learn.

Craig: I think with this recommendation, this might go to the top of my list. Christina is fantastic, plus superb accent. It always helps.

John: It’s just the best. Love it. Love it to death. Tony, we’re here on the occasion of Andor starting its second season. Every listener needs to go back and watch Andor Season 1 immediately. Pause the podcast and go back and watch it. Maybe they’re in their car and they can’t. Could you give us the logline and set us up Andor within the universe of Star Wars for folks who aren’t familiar with what Andor is and why it’s so awesome?

Tony: I’m going to skip the awesome part. The simple setup is it’s the five-year prequel of a character, Cassian Andor, who’s in Rogue One. In Rogue One, he will sacrifice himself at the end in a very heroic, messianic way. This is the five years that leads him into the first scene of Rogue One, which is a slightly odd concept. When we meet him in Rogue One, the character in Rogue One is an all-singing, all-dancing spy warrior. There’s nothing he can’t do.

The concept of the show is to take him from a point five years earlier where he is a cynical, disinterested, self-preservationalist, the kind of guy in his town that people don’t want to see coming down the street, to take him from the lowest possible point, and have him become– In the first season, the first season is really about his stations of the cross on the way to becoming a revolutionary. It’s the revolutionary education of someone from a very outside point of view. We take him, in the first season, just to the point where he will join at the end. This second season is about the next four years as he activates that involvement.

John: Now, that’s centering it on your protagonist, the guy who’s changing, but you don’t limit the POV just to him. There’s other plot lines and things that are being set up, which leads to the bigger question of, what is the show really about? To you, what is the show? What are you actually trying to explore in the course of the show?

Tony: The show, for me, is the opportunity with the largest possible canvas and the largest possible cast and the most resources you can possibly imagine to tell the story of a revolution and to try to tell the story about what happens to a great variety of people and a great variety of social stratus and on both sides of the fence. What happens to ordinary people as revolution just explodes around them and washes over their life?

As people become absorbed into history and the pressures that that places on everyone, to my mind, it’s an all-encompassing opportunity to deal with things I’ve been thinking about my whole life and behavior I’ve been thinking about my whole life and challenges I’ve been thinking about my whole life. I have a chorus. I have a choir, 10 or 15 characters that are really identifiable that we’re carrying through. Cassian Andor, Diego Luna’s character, is this messianic character surfing through the center of that. But as you suggested, it would be a disservice to say that it’s really just about this one guy. It is a broad survey of what happens to people when the shit comes down.

Craig: I’m not going to get into the absolute trap of trying to rate Star Wars stuff because I like my life to the extent that I have one, but I think that Andor does feel apart. It is completely integrated into the story of Star Wars, the history of Star Wars, that narrative, that world, that tone, but it does feel set apart because it’s so– [chuckles] I’m just going to get in trouble. I don’t care. It’s so good. It’s really just of a quality that feels different.

My question. This is really a process/psychology question because I know I’m struggling with this myself right now. You’re about to unleash Season 2 upon the world. There is a Season 3 coming. When you finished Season 1, which was so complete and accomplished, did you think to yourself, “Well, how the fuck am I going to do that again?” How do you face the blank, I don’t even call it the blank page, the blank mind, knowing there is so much work to be done to do another season, another season, another season when you’ve just run a marathon and won it?

Tony: The great crise for us was during the filming of Season 1. Our show was really salvaged as probably other shows were as well by COVID. COVID really saved our show. I started this process either out of ignorance or vainglory or just blithe indifference, whatever. I had no clue whatsoever what I was getting into. I threw together a five-day writers’ room. Things were in process. I won’t go through the whole thing, but I was in London. I was going to be directing three episodes in the spring.

I was prepping them. I was casting them. I was half-assed watching the other scripts come in and going, “Well, I got to go do some other work here.” Had we proceeded on that schedule, it would have been a trade story disaster. It really would have been an epic disaster. COVID came in and everything slowed down and stopped and reset. I reoriented my job on the show. I decided not to direct. I realized where the priorities were.

As we began to crawl back into the process and Disney was one of the first places to start that and Sanne Wohlenberg, who you know well, was so great producer from Chernobyl and we share a lot of things from Chernobyl, but she just was determined. As we started that roll-in, there was time to get our footing and for me to figure out what I needed to be doing and how to make the show potentially what I really hoped it would be. We were on the hook. We had promised that we were going to do five seasons of this show. It was going to be one season per year.

Talk about delusional. It seems so, but that’s what we committed to. We got up in Scotland. Diego and I were up there. This was post-COVID after I went through my quarantine and got back over there and up in Scotland with him. I was just looking into the next black hole as was he because he’s got to marry into Rogue One and it’s 10 years earlier. This is taking 17 years to make the first season. We really knew that we were in trouble.

I literally remember the conversation where we just sat down in the backyard in Pitlochry at this hotel with a scotch and just said, “We’re so fucked. We’re just so totally fucked. What are we going to do?” I don’t want to make this the longest answer ever.

Craig: Go for it.

Tony: The answer was mystically already in front of us. Our show was organized around blocks of three, which is this European system that we– You go for any system. You’re looking for systems that’ll help you-

Craig: Survive.

Tony: – organize things. Yes, survive really, survive really. These blocks of three, a director will do a block of three and three and three and three. We’re doing four blocks of three and that’s what we were doing for the first season. It was like, “Oh, my God. We have four years to cover. Look at this. We have four blocks.” I remember going back to the room and going, “What if I did a year per block? What could I do and would Disney go for that? Would that appeal to them? What would Kathy say? How would we do it?” That was a crucible moment where we really figured out what to do.

John: Tony, can you describe what you mean by blocks? As I watched the first season, it does really feel like this is a movie, this is an arc, and then there’s another one, and there’s another one. Is that what you’re describing?

Tony: A block is three episodes. A director can come in and do three episodes. We do treat them like films. The prep time is probably longer than most films because our demands on the show, which is something we can talk about, are so many extraordinary, extra credit things that you would never think about in any other project. The prep, the building, the editorial team, the whole project is on blocks of these three. In both seasons, it is physically possible for a director to come in and do the very first block and the last block. That would be the only way you’d be able to do the workflow.

John: That’s great. One of the things I really admired about Andor is if we reached a new environment, we’d have a sense like, “Okay, we’re going to be here for a moment.” The prison sequence of the first season is so incredible. I think because you’re doing it as a block, logistically, you’re able to build out these incredible sets and create this space, but also create story elements and create characters who are going to be so important for that sequence.

We also have a sense of, “We will move past them at the end.” It made so much sense. It seems so obvious, but what you’re describing is it wasn’t at all obvious as you were starting the process. You really probably were thinking episode by episode and it wasn’t until you got to this idea of blocks that it became feasible to tell the story the right way.

Tony: No, but Season 1 was built around that system.

John: Okay, great.

Tony: We did build around the blocks. Our very weird writers’ room thing that we did and we can talk about that if you want to. The very weird thing that we did, each writer took a block. Again, you get a chunk. You get a movie. You get these three. Season 1 almost fits that. There’s an anomalous seventh episode, which is an interesting little sidebar. It’s just we weren’t Calvinist about it in the first season. In the second season, because we are jumping a year each time, as writers, it’s a fascinating concept. The idea is we come back, it’s a year later.

Then the idea became refined as I started to sketch it. I’m like, “Oh, my God. You know what I’m going to do? I’m not going to come back and stay a month or dick around and do this thing. We’re going to come back. When we come back, we’re coming back for three days each time.” We just drop the needle on three days and then we drop a year and come back for three days. There’s this abyss of negative space that’s in between. Then my desire, my goal, what we went for is to not have any exposition whatsoever. None of the Chekhovian, “No, John, I haven’t seen you since then.”

[laughter]

Craig: “As you know…”

Tony: None of that. “As you know. As, of course, you remember, when last we spoke,” none of that. What’s the most badass drop we can do and get away with it? This second season adheres very rigorously to the four-movie concept. The show will be released that way as well. They’re going to release them three per week for a month.

Craig: Which I love. It’s amazing that we’re still coming up with new ways to do this.

Tony: I know.

Craig: I’m just thrilled that any movement towards not dumping everything at once to me is a huge victory. I’m curious. This will lead in a little bit to some consideration about your writers’ room and how that works, but showrunning, which is something that you hadn’t been doing. You had been writing movies. You had been writing and directing movies, which is like showrunning a thing.

Showrunning a television show like this, of this size, is somewhat of an elastic job. People do it differently. I myself go crazy. I wonder how you do it. I’m curious how you handle your attention. Where do you hyper-focus? Where do you delegate? How do you keep your hand on the tiller of quality control over the course of this beast because a production like this is an absolute beast?

Tony: Look, you’re absolutely right. I think people are constantly striving for a formula for how to do this. They haven’t even figured out the formula how to make people’s deals on this shit yet, right? Anybody who tells you, “Oh, well, this is how everyone’s doing it,” is lying to you. It is absolutely the Wild West.

I didn’t know what to do. My only experience had been I spent two years on House of Cards as a consultant. I really didn’t go to the room. I went there a couple of times. I was really there as a backup asshole at the end to give notes.

Really, that was my function, to be the final horrible critic of what was there.

Craig: That’s awesome.

Tony: I’d gone to the room and I’d seen it. I certainly had a lot of friends who were doing it. We evolved into– what’s the most graceful way of saying it? We evolved into a system that was a writing system. I never once, for five years straight, have ever, ever, ever stopped writing. I’d never ever, ever had a break, not a single day ever. The writing started in the conception, in the very first conversations with Lucas and Kathy and Disney and everything and tiptoeing into how this might be and what I could get away with and how far we could push it, and should I do this? All that advanced work.

Luke Hull was my next collaborator, the great production designer of Chernobyl, who Sanne Wohlenberg brought over, the great 14-year-old Mozart production designer. I began collaborating with Luke and building Ferrix and building these places and starting to design and getting some sort of handle on what we could afford and what was manageable and what would the scale of the show be.

There’s a writing process with him. I write the first three episodes. I have 100 pages of what I think might be a season. Then I brought in Beau Willimon and my brother Dan. Stephen Schiff was ill in London, so he couldn’t come, but he’d pick up an episode off the notes. Beau and Danny and I go to a room for five days in New York with Luke Hull in presence, with the production designer there who’s already been my co-writer through a whole bunch of stuff in the design sense. The producer is there.

We have lines to Lucasfilm about what we can do and what we can afford. We have this absolutely knock-down, drag-out, accelerated five-day story conference where we beat out the story as crazy as we possibly can and fill in the gaps, all the gaps that I don’t have, and then divvy up who gets the assignments.

Those guys go off and they make drafts. They solve problems. They brought ideas in the room. They make drafts. They do rewrites. We do stuff. They’re always an approximation, right? It’s just such an approximation because those scripts are not going to be done. Well, because of COVID, they’re not going to be shot for 18 months.

Craig: Oh, well, that’s a lovely luxury there.

Tony: Right? There you go. They’re writing and then they go away. Then when COVID happens, all I do nonstop literally every day is write. Our system on the show, I always hear people say, “Oh, well, you have a writer on the set.” Never ever, ever, ever had a writer on the set. Our whole principle is to have the scripts be so prepped, so perfect, have so many meetings and so many design discussions and everything so completely taken care of.

I’ll do the first page turn. I’ll do the first HOD page turn. I’ll run that one. The second one, I’ll scramble. The third one, the final one, is the AD and the director taking over the show. The best version of that is I don’t ever have to say anything. I’ll have a Sunday night phone call with every director before the week’s shooting to go over anything that’s missing or any questions that we have.

Craig: That’s a great idea.

Tony: I want everything so perfect in every moment of tempo and design and everything. Everything’s been tucked away that these people can go to set every day and swing. The TV director thing, that’s a whole other podcast. As a director and as a first final-cut director and as a protective director, the idea of having me or somebody else watch over, I want them to know exactly what they’re supposed to get, what the protein is every day, what we’re going for, but I want them to swing when they go to work.

Our system was developed around that, a very scientific, “Let’s get a perfect set of drawings.” To a level, I would never take a movie. I’ve never taken a movie that far. This is hundreds of people, but so detailed. That’s what we evolved into. It’s a writing system. I wrote from the very first memos to Lucasfilm straight through. We finished November 5th to the final ADR and working with my brother, Johnny, when we’re doing all the final cuts and all the stuff because we get to finish up the show in a way. I don’t finish until the final ADR mix session. I’m writing every single day.

Craig: It sounds like you’re writing through until the point where you have finally finished the scripts. At which point, you now go, and you probably were already doing this anyway, to begin editing because you were now receiving director’s cuts in. Now, you start editing those and you start working on the visual effects. The job never ends, but it sounds like you’ve got a system where the materials that are coming in, it sounds like you’ve got a system where there aren’t too many bad surprises.

Tony: We shot 1,500 pages of script, right? We only lost one scene in the entire thing that we didn’t use for the cut. We only ever re-shot anything, which was the first sequence in the very first episode. Essentially, we re-shot it because we wanted to give the directors the balls to swing away. They were too afraid to swing. It’s like, “Dude, you got to go for it, man. I don’t need coverage. I need a movie here, man.” That’s the only time we ever did it.

Obviously, we had problem-solving complications and all kinds of workarounds because of the strike and different things like that. It is the most maximal, imaginative, immersive thing that I lived in for five years because when I say “writing,” I’m not just talking about the dialogue or the scenes. I’m not just talking about all the memos that I have to write to explain everything that I want or fight for what I need or all those things.

I’m also talking about all the dizzying, really almost hard-to-comprehend amount of design work that has to go into the show. There’s places where I will delegate. Obviously, to the directors. I delegate on the day. Every now and then, the phone would ring at 4:30 in the morning and I’d have to do something, but very, very rarely. Mostly, it’s me getting up at six o’clock in the morning and going through dailies from yesterday and being astonished at how cool these directors are blocking. “Holy shit, look what they did. How did they know how to–“ because they don’t have to worry about the script when they get to the set.

John: Now, Tony, this is your first time doing a second season of a TV show, but all three of us have done sequels. We’ve done movie sequels where we worked on one movie and then we had to come back and do the next one. We have the knowledge of like, we know what the thing is. We can make a plan for the second one. In my experience, you can have a plan for it, but that plan will go awry.

You’re dealing with a bunch of other expectations around it. Because it’s the second time through, expectations are higher and different. What were you able to take from, for example, the Bourne movies from that and bring it to this? Just like, what has been your experience of sequels overall? What are the things that you’ve learned that work well when you’re trying to do the next installment of a franchise versus that’s just not going to be relevant because you’re trying to make a new movie each time?

Tony: I think it’s easier. The first time when I went to do Supremacy, I was shocked that I didn’t have to introduce the character. I was like, “Oh, my God. All the work that you do to have people really understand this person that you’re talking about as quickly and as elegantly as possible, all that’s done.” I think it’s a huge advantage in a way. To the larger question, I think this maybe goes to what you’re saying and maybe the cherry on the top of the previous answer.

I’m no kid. I did a lot of things over the last few decades and a lot of experience of things. I found there were so many days every week where I was using absolutely everything I knew in all aspects of my life. I’m talking about all the ambassadorial things that one does as a showrunner. I’m talking about all of the, “Should I be Ho Chi Minh today or Napoleon?”

[laughter]

Is it time to write that memo? Is it everything from the most molecular scene-writing tweaks to the most maximal decisions about, “Oh, my God. We can’t afford to pay for this entire episode. What are we going to do?” and everything in between? It’s been a decompression process to come off of it, I must say.

Craig: Yes, I go through the same thing. I wonder if you’ve had this existential thought because I have, because you’ve been doing it longer. John and I have been doing it, I think, if anybody is a young person, for a long time.

Tony: I think we’re contemporary.

Craig: We’ve all been doing it for a long time. When you work in features, as you and I and John did for so long, you do get used to a little bit of the, “Well, you work on a thing and it’s maybe a year or if you’re making it two.” This show that you’re making and the show that I’m making will devour, what? A decade, a decade and a half of your life, of your rapidly dwindling life. I wonder, sometimes I turn to my first AD and I say, “When I’m not looking and when I don’t expect it, please hit me in the back of the head with a hammer as hard as you can.”

[laughter]

I don’t know how else to get off of this. Like you said, the dizzying move from molecular to macro at times is exhausting, but I love it. I do feel sometimes a little bit of an ache that there’s something– Well, whatever my Michael Clayton would be, when does that happen? Whenever your next Michael Clayton would be, when does that happen? Do you feel that or are you like, “Screw it. This is a beautiful thing”?

Tony: No, I spent the first year even when I was in London pre-COVID, I began to have just the worst buyer’s remorse. Epic every morning, “What have I done? I’ve fucked my life. I shouldn’t have done this.” Now, I’ve committed. All these people are here. This is horrible. When COVID came, I thought like, “You know what? Thank God. That will kill the show. Thank God.” I was very, very unhappy when the phone calls started coming. Then I was like, “Well, I’m not coming back to London to die for this show.” Then they were like, “Well, I’m not going to direct anymore.” It’s two speeds.

Number one, you have your pride of work. That never goes away. I think anybody who gets onto this podcast is probably in that category of obsessive human being. You’re just going to do the best you can all the time, but it was with horrible, horrible doubt. It really wasn’t until we started shooting and stuff started coming in and it started to pull together. My brother Johnny really came in and was really seeing stuff. I was like, “Well, this is going to be good.” My feelings changed as we did the first season. I’m only doing two, though, Craig. It’s five and a half years for me. I did do Rogue, but that was in the past.

Craig: You’re not only doing two. I don’t believe that.

Tony: I’m only doing two. We’re done. No, it’s a closed circle.

Craig: This is it? It’s over?

Tony: Yes, no, it’s a novel. Yes, because we’re taking him to the final scene that walks him into Rogue One.

Craig: In Season 2, yes.

Tony: Yes, literally, we’re walking him and I will say that is–

Craig: You found a way to get out.

[laughter]

Tony: Not only that, I think it let us stay sane. It let Diego and I stay sane and the people involved. It let Disney stay sane because there’s no secret there. The streaming model and economics changed right in the middle of our show, which could have been cataclysmic.

Craig: You’re in a victory lap now then.

Tony: Yes, but knowing the ending, always knowing the ending, made everything much more. It’s a freeing thing. It’s a liberating thing to know where the end of the road is.

Craig: Well, I know where the end of my road is. It’s just way the fuck down.

[laughter]

Tony: Well, I don’t know what to tell you.

Craig: I don’t know what to tell me either.

Tony: No, I’ve been out. I wrote another script over the summer, so I’m trying to get out.

Craig: Screw you, Gilroy. [laughs]

Tony: No, I’m out.

Craig: All right. Well, that’s a good answer and that’s encouraging. I like how happy you look right now. We’re looking at each other on Zoom. You look delighted. Just check in with me about five years from now. I hopefully will have that same, “I did it,” look on my face.

John: Yes, we’re an audio podcast. If we ever released a video episode, you could see Craig, the realization. They’re like, “Oh, Tony Gilroy’s done? That’s a choice I could have made?” You can see it recalculating everything he did.

Tony: I know. He’s shrinking there.

Craig: That was just my rage building up. That’s what that looks like. [laughter]

I love working on the show, but my God, the marathon aspect of it, at times, it’s incredible. Congratulations for making it to the end of the finish line.

John: Is there a way that we could manufacture a COVID?

Craig: Oh God, Jon, what are you saying?

Tony: Dude, I think they did that. They tried that.

John: Craig’s show actually has it built in. Is there a way that we can build in those times and the stuff because that was so crucial for you to be able to make it the first season?

Craig: Yes, I’m curious because you had the benefit of that forced break in Season 1. Now, in Season 2, as you were working on it, there was a forced break, but you couldn’t work during it because it was the Writers Guild strike.

Tony: Yes, but that was a different–

Craig: You were in a different spot.

Tony: The irony of that was that if you had asked me at any point during that year, “What’s going to be the most epic moment of your year,” I would have said, “Without any labor issues on the horizon whatsoever, I could have told you in September.” Oh, my God. Around March or April, I’m going to finish the final rewrite on the final script. That’s my timeline. I’m ahead of the production. I don’t want to minimize the work that Danny and Beau and Tom Bissell and Stephen– they make the rough-housing that we can cast and build and budget and everything.

My work to finish it and to get there and to tweak it all out and to get it off this desk, I was looking, “Oh, my God. Around March, the way I’m going, that’s where I’m going to finish.” I literally finished the final page turn about six days before the strike. It rhymed with that just by accident. The problems with the strike were production problems and it’s a whole different shit. It didn’t help me out.

Craig: It didn’t really help anyone out, I think, other than-

Tony: No, it didn’t help me out.

Craig: -the membership as a whole, which I guess was the point.

Tony: I’ll tell you one thing it did and this is interesting. What it did do is I was not allowed to see the show for six months.

Craig: Oh, that’s interesting.

Tony: They kept going. I had only seen one cut of one rough cut of the episode. In September, when the strike was over, my brother John came to New York and brought me all 12 episodes in extremely rough form, but all 12.

John: That’s amazing.

Tony: With temp crap and all the IOUs and temp music and sloppy shitty all over the place but 12. I was extremely nervous. I spent two days and I watched them. I had the experience that one always speaks about in an editing room. On every movie I’ve ever been on, there comes a moment where you go, “God, I’d pay $50,000 if I could see my movie for the first time.”

Craig: Right.

Tony: I got to watch all 12 episodes on a run with the freshest eyes and smart fresh eyes that you could possibly ever have. I generated, I don’t know, 100 pages of notes, but they were notes that were like I had developed a new way of thinking about things in a way where I’m really into the calories that the audience spends on information. I’m really sophisticatedly into that.

Craig: Describe that concept a little bit for us.

Tony: If the audience is worried about any bump in the road over here or if that’s confusing when they come in or something that she said takes my energy away and the audience is missing the protein that I have in the middle of there that I want to be there, I want to smooth that down or get rid of it. I was so much more in tune with that in a way that I never would be holistically before.

I think I generated, I don’t know, hundreds of pages of ADR and all kinds of– it was a superpower to go back to London a week later. I think we had the most exciting two weeks that I’ve almost had on the show, getting back to London after that cut and going– all four cutting rooms, all four directors, and just going like, “Okay. This is what I do here. This is this and this isn’t working. Let’s do this,” and like, man, people, it was so much.

Craig: Those are fun. Those are the fun weeks.

Tony: Yes, and so the strike in that sense maybe had a positive effect. Boy, I wouldn’t want to do it that way again.

[laughter]

Craig: Once is enough.

John: It’s like asking it to be severed. There was two Tonys and like, “No, it’s appealing,” but also, clearly, you see the damage there.

Tony: It was so much heartache for Sanne and the people in production. The work that they did was just heroic and my brother. Not to be repeated, but, again, you’re always trying to make an advantage out of something that’s a crise, right?

John: A crise is a crisis. It’s the second time you used that word.

Tony: Yes, a crisis, yes.

Craig: It’s a French crisis.

Tony: That’s the word I’m going to use. That’s the word you’re going to–

John: In your bonus segment, you’ll get more on a crise.

Craig: Yes, he’s already found the word for his word.

Tony: Exactly.

John: Craig, I’m taking from this. Calories, protein. Twice you mentioned protein, the protein of a scene. Love that. That’s so important because like everything else, lovely, makes things taste better, but the protein is the actual substance that you’re trying to make sure.

Tony: Why are we here? Why are we here?

Craig: We talk about writing sometimes like it’s a little bit like the way magicians practice the art of deception and distraction. If they are looking at the hand you don’t want them looking at, you need to figure out how to get them to not look at the hand you don’t want them looking at. You want them over here. Those little bumps, the tiniest bump is too much of a bump. I love that you talk about that.

Tony: Really, in my later career, I’m vastly more conscious of my relationship with the audience than I ever was before. Not in a pandering way but in a communicative way.

Craig: Yes, I love that.

John: The real trick of the writing that we do is we have to simultaneously know everything that’s going to happen and divorce ourselves of all memory. We have to both be the creator and the audience simultaneously. It’s every word on the page and every frame is that split.

Tony: Exactly.

John: Let’s go to some listener questions. First one here is an audio question. Drew, help us out. You can place this question from Jason in Canada.

Jason: “Back in 2021, I wrote and directed my first short, a ridiculous sci-fi comedy titled, I’m Not a Robot, about a man who, after failing a CAPTCHA test trying to log onto a website, faces an existential crisis when he thinks he might actually be a robot. If the title and premise sound familiar, it’s because Victoria Warmerdam just won the Oscar for Best Short Film for her, I’m Not a Robot.”

“It was funny hearing from friends and colleagues joking that my film was nominated for an Oscar, but this got me thinking how interesting it is that two writers, an ocean apart, came up with and created such similar short films within a few months of each other. Maybe that’s a sign that the idea was in the zeitgeist or that the idea wasn’t that original, but either way, it is cool that another writer felt like an existential crisis triggered by the mundane task of clicking on images of bicycles to prove their humanity was a story worth sharing, and even cooler to see Victoria recognized for her incredible work.”

“As Craig has said before, and apologies for paraphrasing, but it’s less about the idea and more about the execution. Victoria certainly executed at the highest level. With that in mind, I still feel oddly validated. My first no-budget film did not win an Oscar, not even close, and I had nothing to do with Victoria’s Oscar win. At the same time, I wrote something that felt true to me and another writer felt that way too. I was curious if, as writers, you’ve ever experienced something similar where you saw one of your ideas or stories brought to life by another writer. If so, did any interesting similarities or differences stand out? Your friend in the North, Jason.”

Craig: I love our friend in the North. That’s so nice.

Tony: Painful, painful, painful, painful. Yes, many times, many times. It’s the one reason why one should avoid the idea that you’re better off isolating yourself away from entertainment news and staying on top of the industry and keeping your ear to the ground, and if you live in New York or you live in London, you live away, making sure that you have an agent that has their ear to the ground.

I’ve had several, many things shot out from under me when I’ve realized someone else was doing it or there was something that was close. It’s really painful when you go deep. It’s really painful when you go all the way through and find out that you’ve been treading the same territory. You have a remarkably generous attitude about it. I’m hopeful that you’re a complete human being and there are some other painful conversations about it.

Craig: Oh yes, I’m sure.

John: There was a journey of acceptance to get there, I hope.

Craig: Jason can feel pain.

Tony: It sounds a little valium to me.

Craig: Well, I think you’ve probably had the experience a few more times than Jason has. There is something, I think, at least nice to say, “Listen, I’m just starting out. I’m aspiring.” At least the thing that I thought would be interesting conceptually turns out to be interesting conceptually to somebody, which is– It’s funny. This was in the zeitgeist because I remember that Ron Funches, who was a fantastic standup, did a joke about this very thing where he said, “They keep on asking me if I’m a robot and they make me enter a series of numbers and letters,” which seems like the sort of thing a robot would be really good at.

[laughter]

Tony: Oh man, this hurts. This question hurts. PTSD.

Craig: All right. Well, Jason, you’ve triggered Tony Gilroy, so another feather in your cap.

John: For me, that example was this movie, Monsterpocalypse, I wrote for DreamWorks. Tim Burton was attached to direct it. I turned it in and they’re like, “Oh wow, we really love this. Oh wait, there’s a movie called Pacific Rim and it seems like it has a similar premise.” They found that Pacific Rim is like, “Oh Jesus, it’s the same movie.” It really is. It’s just way too close. It was a Dante’s Peak versus Volcano situation where it’s just like they didn’t want to be the second movie. I’m like, “I get it.”

Craig: They did those, though. They did both of those.

John: They did those and it didn’t help.

Craig: They did Bug’s Life and Antz.

John: They did, yes. Sometimes they will do both things and sometimes it works out.

Craig: Sometimes they’re like, “Screw it. Let’s just do it.”

John: They decided not to do mine and it’s like, “Okay.” I wish I were as immediately accepting as Jason was, but it’s tough.

Craig: Jason is just clearly far better balanced than the three of us.

John: Hey, Craig, I do want to hold on to this example for the next time we see a story in the news about like, “Oh, this person stole my script or stole my idea.” Come on. It’s the same title, the same idea.

Craig: You know what? Great point. I love Jason for, A, being an incredibly positive person, which is really cool, but B, not going anywhere near the whole, “They stole my thing.”

Tony, John and I are obsessed with the following concept that if there were justice or, I don’t know, some really good journalistic standards in the entertainment reporting business, you would never hear a story about somebody filing a lawsuit saying someone stole their thing. You would only hear if they won. That meant you would never hear anything because they never win. I’m not saying that people don’t occasionally infringe. I’m sure infringement occurs, but I just love that Jason didn’t go down that path.

Tony: I’ve been ripped off.

Craig: Of course, you’ve been ripped off. You’re really good.

Tony: I’ve been ripped off. I’m not going to get into it, but Danny and I really early in our career got ripped off.

Craig: Did you sue?

Tony: No, we were advised by an agent because we didn’t really have an agent. We were hip-pocketed at that point. They said, “Look, you could do this. You might get over on this and these people might put you to work even, but you guys look like you might be around for a while and this might not be the best thing to do.”

Craig: There you go. “You guys look like you might be around for a while.” I guess, listen, I got ripped off too in the beginning of my career. It happened and it hurt, but then people said to me, “This is not your last at-bat. Just eat this one. Get back out there. You’ll be fine.” It’s not fun. Anyway, I appreciate that Jason didn’t go down that road.

John: Drew, another question here.

Drew Marquardt: This next one comes from Anonymous. “Could being a film critic or film journalist affect your chances of working as a screenwriter? As someone currently looking for work and with a background in journalism, I personally really enjoy writing about film and I feel like it could be a great avenue for me as a young person starting to build a career, but I’m afraid of costing myself future opportunities by being granted a film critic. Perhaps it makes me look bad or someone doesn’t like something I said about their work. Is that a real concern?”

Craig: Stephen Schiff.

Tony: Look, a good script’s a good script. If you’re lucky enough to write one, someone’s going to pick up on it.

Craig: Could not agree more.

Tony: Everything else is a moot point. Nobody gives a shit.

Craig: You could absolutely destroy someone’s mom’s movie. If you write a good script three years later, they’ll buy it.

Tony: They’ll put their mom in it.

Craig: Stephen Schiff was the chief film critic for The Atlantic, I want to say?

Tony: Vanity Fair.

Craig: A really big film critic and then one day said, “I think I’m just going to try doing this,” and has been doing it at a very high level ever since. As much as film critics can make me nuts, I’m on record with that one, no, as long as you’re not a complete jerk. If your persona as a critic is jerk or if you go down the Armond White, “I just like disagreeing with everybody,” maybe then, maybe. I agree with Tony. Write a good script and all is forgiven.

John: I would also say that there’s a difference between being the critic who is reviewing every movie that comes out this week and trashing them or giving the thumbs up and the thumbs down and being the person who writes very smartly about movies and the overall trends in movies or things you notice about who can pull out themes among different directors and different films.

That’s the kind of thing which is elevating the art of film criticism and making us think about film. That’s a different thing than just trashing the new thing each week and saying how bad the most recent Disney adaptation is. That’s not doing you any favors. If people are googling your name to see that kind of stuff, that ain’t going to help you. If you’re writing really smartly about film like Stephen Schiff, that’s fantastic.

Tony: Then wait for your first review.

John: Nothing will help you out more there.

Craig: That’s when you-

Tony: Karma.

Craig: -fucked around and you found out [laughs] because, good Lord, that hurts.

John: I will say there have been some cases where I’ve seen a person who does film criticism who then goes off and makes a movie and it’s just terrible. It’s always fun to see like, “Oh, you know what? Criticizing a thing and actually making a thing are very different skills.”

Craig: Absolutely.

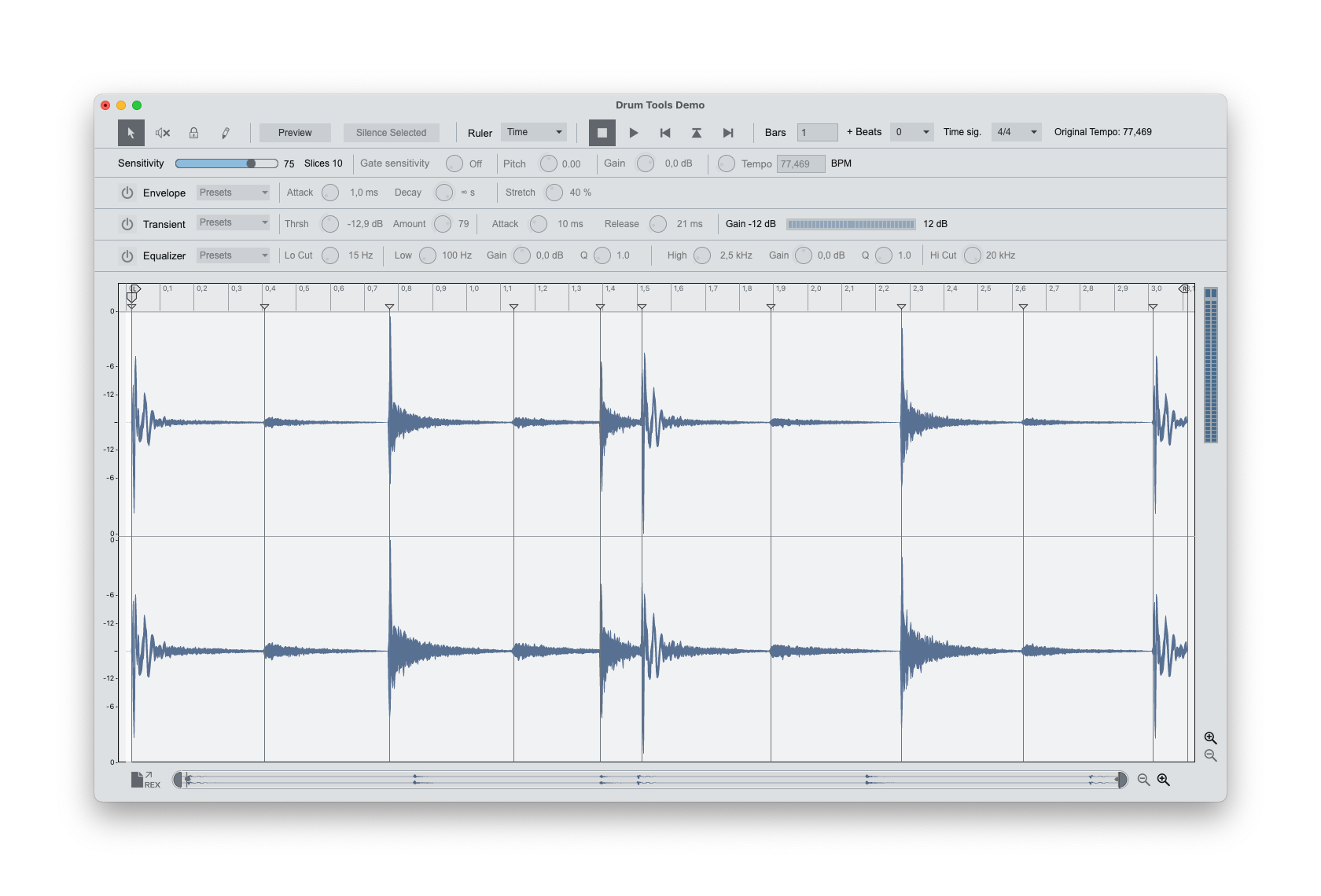

John: I love that. It is time for our One Cool Things. Craig, what do you have for us?

Craig: Today, it’s something that I mentioned on the podcast before in passing, but I wanted to drill down a little bit into it because I use it literally every day now. It’s called Startpage. I don’t know about you, guys. I’ve been looking for an alternative to Google for a long time because the company that says don’t be evil has become evil. The problem is the other search engines just aren’t very good or they’re slow, but Google is giving me the AI slop all the time.

Startpage is a company that’s run out of the Netherlands. They aren’t their own search engine. What they do is they take your search query and they run it through Google or Bing if you prefer. They don’t save your search information and they strip away all the trackers. Google doesn’t know who you are. They don’t save any of your stuff. You get to Google without becoming a product of Google. It’s just as fast, just as good, and no annoying AI slop. The last thing you might want to google with actual Google is Startpage. Install it–

John: It’s actually just startpage.com.

Craig: There you go. Go to startpage.com and it’s been a delight.

John: Craig, I was trying it out because I saw it here in the show notes and I think it looks great. I really agree with it and I want to try to use it. One frustration I have is that in Safari and other browsers, you can set your default search engine. You can just type in the bar to get a thing. Right now, you can’t set startpage.com as the default search engine.

Craig: You can.

John: Okay, so tell me how you’re doing it.

Craig: Well, I’m using Chrome, so that may be the part of it is that I’m not using Safari. In Chrome, I think there is an extension or something that allows that to happen.

John: Okay, but it’s certainly worth considering because I really do think it’s a better way to do stuff. Tony, what do you have for us for One Cool Thing?

Tony: Can I name a podcast without getting in trouble?

Craig: Are you kidding me?

John: 100%, we love it.

Tony: It’s not a competitive one. My salvation for the last year and a half has been, I think, the greatest podcast I’ve ever heard. It’s called A History of Rock Music in 500 Songs by a guy named Andrew Hickey. There was an article about it in The New Yorker last year. I can’t remember who wrote it. It wasn’t Adam Gopnik. It was somebody else, but it was an appreciation of this. It said, basically, this is the equivalent of one man trying to write the OED, the Oxford English Dictionary. He’s only up to 170. He just dropped 177 this morning.

I literally got a new one this morning. I don’t know if he’ll possibly survive to finish it. I cannot recommend this enough. If you’re into music, I was turned onto it. I started listening to ’60s stuff that I was really interested in and British Invasion and different things. I worked through that and then I chipped away at some other things. Finally, I was like, “I’m just going to go back to the very beginning and start at the beginning and go all the way through.” It has been a place of great safety and curiosity.

Craig: Love it.

Tony: That’s my recommend. He always says at the end, “If you like this podcast, please recommend it because word of mouth is the most important communicator.” This is my appreciation of Andrew Hickey. It’s on Patreon, but it’s on Spotify. It’s fantastic.

Craig: Awesome.

John: That’s great. Andrew Hickey did the thing, which we cautioned against, which is you’re starting your premise like, “I’m going to do 500 episodes of this thing,” and then you’ve boxed yourself in there. Maybe he’ll find some block format just to get through that.

Craig: We should have done that because we would have been done years ago, John.

Tony: I’m just going to say one thing, guys. I’m going to tell you one thing. If you ever listen to this, you’ll clearly understand that he has to put a lot more into it than you guys are doing.

John: Yes, absolutely. It’s not just two people chatting on microphones.

Craig: What we did put into this, John did 99.3% of.

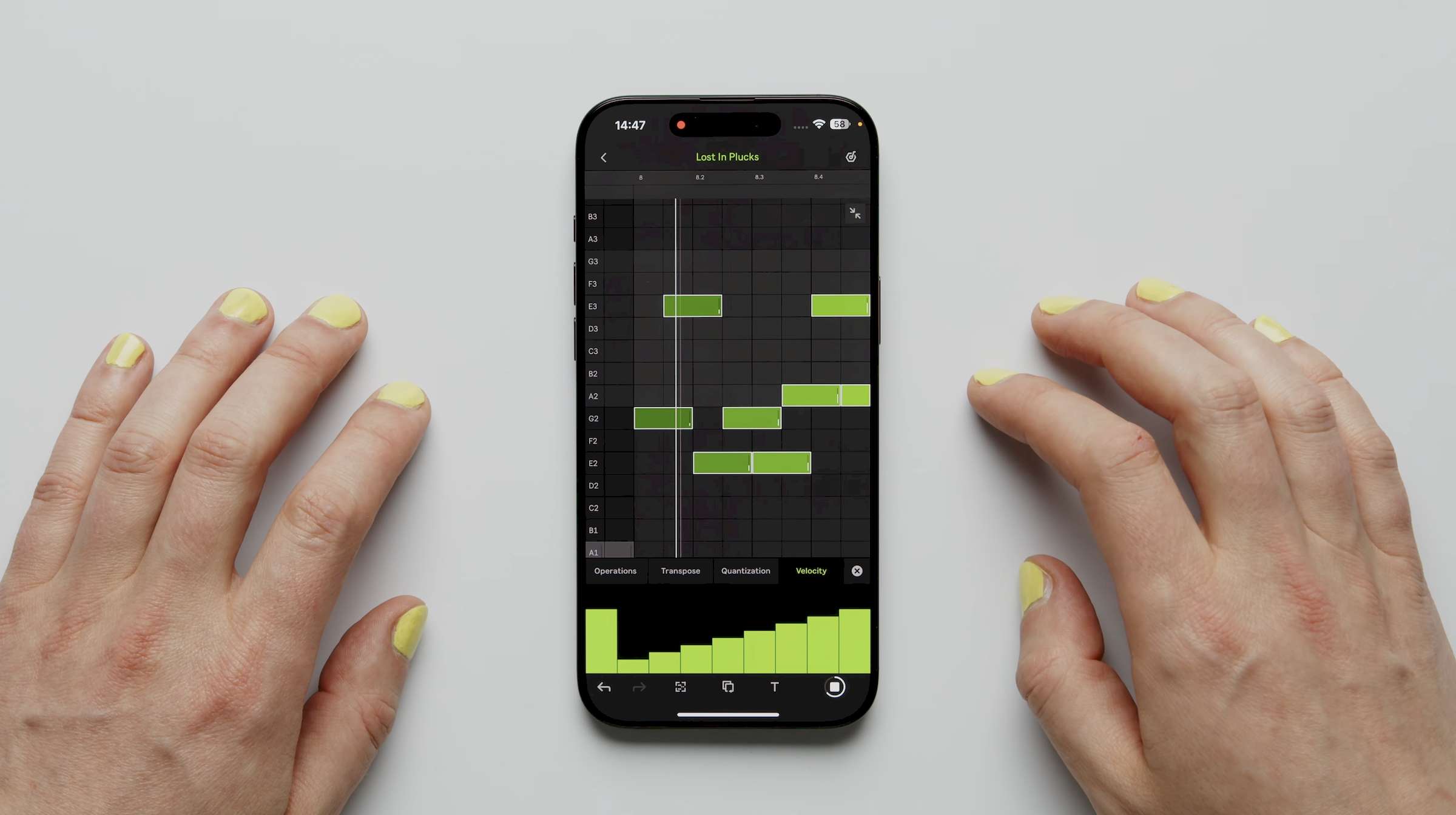

John: Andrew, yes, it’s that. My one cool thing is like Craig’s. It’s a utility I find super, super helpful. Basically, you’re surfing the internet. You’re buying stuff and there’s a site, an article that you want to hold on to. You want to set a bookmark for it. You could save it in your browser, but then you’re never going to actually find that again. You have to find some place to store that thing.

For the last 10 years or so, I’ve been using a service called Pinboard, which is a bookmarking service. You save the link and you put a little tag on it, so if I remember if it’s how it would be a movie or a one cool thing. Pinboard is clearly near the end of its life. It has not been updated for a long time. I knew it’s going to just fall apart at some point. I have 4,000 bookmarks saved someplace.

I was considering rolling my own because I’m a masochist, but then I found a service called Raindrop, which is actually really good. It’s raindrop.io and it’s just a bookmarking service. You click a button. There’s a little browser extension and it saves it. You put a little note for it, put a tag on it. Then you can always just search it and find it, which is really good. What I like about it is it has a native app for iPad and for iPhone.

If you’re looking on your phone, you tap the little share sheet and you just save it to Raindrop and it’s there. If you’re looking for a way to hold onto your bookmarks and organize them in a way that you’ll actually find stuff again, I recommend it.

It’s good and it’s a paid service. You’re paying for this to get the premium stuff. I like paid services because then they’re going to stick around because they have an incentive to stick around. Raindrop.io if you’re looking for a bookmarker.

Craig: It’s an actual business model in tech.

John: Yes, that’s where I think it’s like when you don’t pay for a thing, it tends to break and fall apart because people abandon it.

That is our show for this week. Scriptnotes is produced by Drew Marquardt and edited by Matthew Chilelli. Our show this week is by Spencer Lackey. It’s an homage to The Last of Us, Craig.

Craig: Oh, I got to listen to this one.

John: Yes. If you have an outro, you can send us a link to ask@johnaugust.com. That is also a place where you can send questions like the ones we answered today. You’ll find the transcripts at johnaugust.com along with a signup for our weekly newsletter called Inneresting, which has lots of links to things about writing. We have T-shirts and hoodies and drinkware. You’ll find us at Cotton Bureau. You’ll find the show notes with the links for all the things we talked about today in the description, but also in the email you get each week as a premium subscriber.

Thank you to all our premium subscribers. You make it possible for us to do this each and every week and to pay the talented folks who put it together. You can sign up to become a premium member at scriptnotes.net. We get all those back episodes and bonus segments like the one we’re about to record on which words we wish existed in English. Tony, Craig, an absolute pleasure talking with both of you. Congratulations to both of you on your new seasons. I’m so excited to watch it.

Craig: Thank you, Tony.

Tony: Really gassed. Really happy to be here. Thank you.

[Bonus Segment]

John: All right, Drew, can you help us out? We have a question here from Jean-Philippe.

Drew: Jean-Philippe writes, “I’m a Québécois screenwriter and I needed to share how incredibly envious I am of screenwriters who write in English specifically because of two precious golden verbs, “to gasp” and “to scoff.” These beautifully concise words simply have no practical equivalent in French, yet they’re extremely useful in a screenplay as they’re a way to describe elements of nonverbal communication that are very common. What are the words that you find most useful for screenwriting and what thing do you wish there was an English word for? To all the screenwriters who work in English, be grateful for your great language.”

Craig: You don’t hear that from a French speaker too often, I got to go say. Thank you for that, Jean-Philippe.

John: As we’ve talked about on the show before, English does have just a huge vocabulary because of the way it accumulated words from French and then German and all this stuff and all of that smooshed together. We got duplications of things and we are very sound-rich, so it’s very easy for us to import words and make them work. The obvious example is “schadenfreude,” which is such a useful term that we just borrow the German word. We can say it in English because we can say any word in English, which is so useful.

I was at breakfast this morning and I realized, so you’re eating food at a restaurant and you’re enjoying it and then there’s a moment, a tipping point where it’s like, “Get this plate away from me. I don’t want this plate in front of me. I want it to go away.” There feels like there should be a word for that and there’s not a word for that. I want there to be a word for that term. Can you guys think of anything to describe that? Do you know what I’m talking about?

Craig: Oh sure. Sure, yes, it’s like food repulsion.

John: Yes, it’s like a disgust, but it’s a tipping from like, “This is delicious to–“

Tony: Yes, we should have a word for that. You’re absolutely right.

John: I was looking and Spanish has a verb, “empalagar,” which is to become overwhelmed and sickened by something that was enjoyable, but it’s really relating to something that’s too sweet and too-

Craig: Like cloying or–

John: -cloying. Then French has “écoulement,” which is also that disgust or aversion. It’s a little bit more than nausea, but it doesn’t really refer to that, the tipping point.

Craig: Yes, you’re talking about when something flips its polarity from love to hate.

John: Yes.

Craig: The Germans surely have a word for this.

Tony: Grossbundance. Yes, grossbundance.

Craig: Grossbundance. I like grossbundance.

John: Grossbundance. Yes, grossbundance, yes. It’s that fork-drop moment where it’s like you just can’t take it anymore. I want that word to exist. If our listeners have good suggestions for it, what are you guys thinking? Are there words you long for in other languages or things you feel like should be encapsulated in a word that just don’t exist in a word?

Tony: I’ve used the word because it gets it done, but I wish there was another word for “gobsmacked.” It’s a good word and it’s effective. Every time you type it, you’re like, “I wish there was something else for gobsmacked.” Total incredulity. I seem to find so many characters in my shows are-

Craig: Gobsmacked.

Tony: -massive quantities of incredulity. I wish there were more words like Eskimo words for snow for the feeling of not being able to believe exactly what’s– and not going, “What the fuck,” either. I’ve done that too.

Craig: Jaw drop?

Tony: Yes, I know.

Craig: Drop jaw. Yes, that’s a tough one.

Tony: They’re all a little mundane.

Craig: That’s absolutely true. It’s funny, the thing that I yearn for the most isn’t actually a different word. It’s a different punctuation mark. There has to be something between a period and an exclamation point because, to quote our friend Christopher McQuarrie, every time you put an exclamation point in a script, you’ve failed.

[laughter]

Craig: I know. Tony’s like, “That’s every fucking page.” We rarely want someone yelling. I’m actually curious. This is a side note because, Tony, you wrote The Devil’s Advocate, which I’m obsessed with. There are sections where Al Pacino fully yells paragraphs. I’m curious if those were exclamation-pointed or if he just took off on his own. He might have taken off on his own there. [chuckles]

Tony: Yes, I think it was a collaborative. Those were all done. They were all written for Al and rehearsed at the apartment. There were 20 other ones that we didn’t do. I think it was an era of exclamation points.

Craig: I wish there were something that said emphasis, but it wasn’t more than a period, which feels like just meh, but not quite an exclamation point.

Tony: You know what I don’t like, though? I don’t like when they take a transcript of your interview and then they add exclamation points where you never meant it to be.

John: Oh, God.

Tony: You’re like, “I’m not a–” Really? Did I sound like that?

John: You did not.

Tony: No.

Craig: No, none of us sound like exclamation-pointy people.

Tony: What? How did you decide to put that there?

Craig: Well, here’s a word that I wish I had and maybe there is a good German word for this. We always look to the Germans for these words. That is a simple thing to put in parentheses that says, basically, the thing that I’m about to say now, I believe the opposite of. Now, you could say “lying,” but lying doesn’t give you the full picture of, “Did you kill her?” “Absolutely not.” Lying is not enough. Full denial, complete lying, but then you’re giving it away. There’s no evocative nature for framing something as a particularly good lie because I love when characters lie.

John: That’s great. I think what we’re distinguishing in between is there’s the words that would be so helpful to have in scene description or in parenthetical versus seeing the words people are actually going to hear in dialogue. Those could be different things. In dialogue, through performance and through shading, we can get the meaning across. Sometimes you just really desperately want that thing that encapsulates the idea so clearly and it’s hard to find.

I was googling around to see what other words people were longing for. I found two words that got mentioned a lot. First is “toska” in Russian, which is a soul-deep ache, a vague, restless yearning that can’t be named or satisfied. Nabokov said, “No single word in English renders all the shades of toska.” I get that. You know what that’s like, but maybe you don’t really know what that’s like unless you’re Russian.

Craig: Russians really do know what that’s like. They’re born with that.

Tony: Duende is like that. Duende, the Spanish word “duende.” A lot of people wrote about duende. I think Hemingway wrote about the lack of duende. The word that you’re just describing, the words that take on a whole– because people have tried to think, they bring their own luggage with them. They bring this extra sparkle. Maybe we should leave them as they are and use them. I’ve used duende.

Craig: Why not? We took “ennui,” which is the bored version of duende. Let’s take it.

John: Yes, absolutely. We took schadenfreude. The other word that was brought up, which I thought was great, is “cafuné.” It’s a Brazilian-Portuguese word for the act of running your fingers through someone’s hair out of love. It’s not the verb. It’s the noun version of it. It’s like, “Yes, that’s really nice.” In English, we can convey that with a lot of words to actually do that. It’s not just running the fingers through someone’s hair. It’s specifically why you’re doing that and it’s a good image. It’s a powerful word.

Craig: John, you and I love it when our spouses run their hands through our hair.

John: Absolutely. Our baldpates, yes.

Craig: It’s sort of shyness.

Tony: I wasn’t going there.

Craig: You buff us a little bit. [laughs]

Tony: I was not going there.

Craig: Listen, Tony, you’ve got a lovely head of hair. We’d like to congratulate you on that.

Tony: Yes, I know. I wasn’t going there.

[laughter]

John: All right. Referencing back to Jean-Philippe’s question, I think we agree that, yes, English does have an abundance of words, but we could always use a few more. If people have good suggestions for the words that we’re lacking, email us. Let us know and we’ll put those in follow-up.

Craig: Fantastic.

John: Tony, thank you for sticking around and talking through some words that we wish existed. A pleasure.

Tony: It’s a gas to be in the tribal community. Thank you.

Craig: Thank you, Tony.

John: Thank you.

Links:

- Tony Gilroy

- Here’s a recap of Andor Season 1!

- Andor Season 2: Trailer 1 | Trailer 2 | Special Look

- Episode 680 – Writing Action Set Pieces with Christina Hodson

- I’m Not a Robot short by Victoria Warmerdam

- I’m Not a Robot short by Jason Speir

- Stephen Schiff

- Startpage

- A History of Rock Music in 500 Songs

- Raindrop

- Get a Scriptnotes T-shirt!

- Check out the Inneresting Newsletter

- Gift a Scriptnotes Subscription or treat yourself to a premium subscription!

- Craig Mazin on Instagram

- John August on Bluesky, Threads, and Instagram

- Outro by Spencer Lackey (send us yours!)

- Scriptnotes is produced by Drew Marquardt and edited by Matthew Chilelli.

Email us at ask@johnaugust.com

You can download the episode here.The post Scriptnotes, Episode 682: The Second Season with Tony Gilroy, Transcript first appeared on John August.

![Players Can Now Check In to ‘The Cecil: The Journey Begins’ on Steam [Trailer]](https://bloody-disgusting.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/cecil.jpg)

![‘The Bondsman’: Kevin Bacon & Erik Oleson On Demon-Hunting, Musical Redemption, ‘Tremors,’ Marvel, DC, & More [Bingeworthy Podcast]](https://cdn.theplaylist.net/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/04152419/THE-BONDSMAN_TRAILER_KEVIN-BACON_AMAZON-PRIME-VIDEO_APRIL-3_.jpg)

![Naming Your Baby? That Choice Could Haunt Them On Every Airline Upgrade List [Roundup]](https://viewfromthewing.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/upgrade-list.webp?#)

.jpg)