The 4 Parenting Styles (And Which One Is Best)

I’ve been doing this dad thing for almost 15 years now. During that time, I’ve read books and articles about how I can be a better parent. One parenting framework I’ve found helpful in rearing my kiddos comes from a child development researcher named Diana Baumrind. Back in the 1960s, Baumrind observed how parents and […] This article was originally published on The Art of Manliness.

I’ve been doing this dad thing for almost 15 years now. During that time, I’ve read books and articles about how I can be a better parent.

One parenting framework I’ve found helpful in rearing my kiddos comes from a child development researcher named Diana Baumrind.

Back in the 1960s, Baumrind observed how parents and children interacted in their homes. During her studies, she noticed parents typically resorted to three parenting styles. She also observed that each parenting style was usually associated with a corresponding outcome in child behavior and well-being.

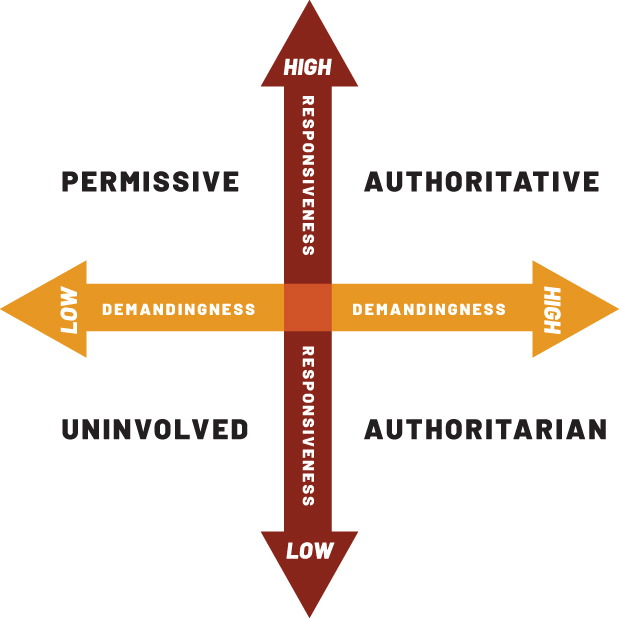

Baumrind argued that parenting styles can be placed along two dimensions: responsiveness and demandingness.

According to Baumrind, varying mixtures of responsiveness and demandingness resulted in several different parenting-style typologies.

In today’s article, we’ll unpack what these styles look like and which, according to Baumrind (and subsequent childhood researchers), is the best for kids.

The 4 Parenting Styles

First, some definitions of responsiveness and demandingness:

Responsiveness (based on the level of warmth/supportiveness). This is all about how emotionally responsive and attuned a parent is to their children. A parent high in responsiveness is nurturing, affectionate, and accepting. Low-responsive parents are cold, rejecting, and uninvolved.

Demandingness (based on the level of control/expectations). This is about the extent to which parents set rules and expectations and enforce discipline. High-demand parents set high expectations for their children and consistently enforce those expectations. Low-demanding parents place few expectations on their children and rarely enforce the few rules they establish.

These two dimensions can be visualized on an x/y axis, with responsiveness occupying the x-axis and demandingness forming the y-axis.

Let’s unpack each quadrant:

Authoritarian Parenting (Low Responsiveness/High Demand)

The authoritarian parent is low on responsiveness but high on demandingness. This is the “because-I-said-so” parent who expects immediate obedience without explanation. Rules are non-negotiable, consequences are often harsh, and warmth can be in short supply.

Let’s say a kid throws a tantrum because he doesn’t want to stop playing video games to do his homework.

An authoritarian parent’s response to this situation might sound like: “Stop being lazy and do your homework now! We are not going to discuss this! And if I catch you on your Switch before it’s done, you’ll lose it for a month.”

Kids raised with the authoritarian parenting style are more likely to be socially withdrawn, more likely to be anxious or depressed, and might have behavior issues when they hit adolescence. The authoritarian parenting style doesn’t help children develop an internal locus of control. They don’t learn how to govern themselves because they’ve always had a parent to tell them exactly what to do.

Permissive Parenting (High Responsiveness/Low Demand)

The permissive parent flips the script of the authoritarian parent. They’re high on responsiveness but low on demandingness. This parent is warm and nurturing but sets few rules or expectations for their kids. Rules are always negotiable. They avoid confrontation and often treat their child more like a friend than someone they’re responsible for guiding.

To the child who doesn’t want to stop playing video games to do his homework, the permissive parent would say something like, “You don’t feel like doing homework right now? That’s alright, sweetie. Maybe work on it later, okay?”

As might be expected, kids with permissive parents struggle with self-discipline and impulse control, are more likely to be self-centered, and can have a harder time following rules in school or other structured environments.

The children of permissive parents often get the message that their wants should always be accommodated, which doesn’t prepare them well for the real world, where limits and frustrations are inevitable. They tend to flounder in adolescence and young adulthood.

Neglectful Parenting (Low Responsiveness/Low Demand)

Baumrind initially didn’t include neglectful parenting in her typologies. It was added later by child development researcher Eleanor Maccoby.

The neglectful parent is low on both responsiveness and demandingness. This parent offers their kids neither guidance and structure nor emotional support and nurturing. In extreme cases, the neglectful parent may fail to even meet their children’s basic needs.

A neglectful parent doesn’t care if their kid plays video games or does homework. If their child is having a hard time in school, the parent doesn’t even bat an eye. They’re just completely zoned out when it comes to caring for their children.

Not surprisingly, kids raised with this style tend to fare worst of all. Research shows that children who grow up with neglectful parents often develop attachment issues, are at higher risk for behavioral problems, and are more likely to engage in delinquent behavior.

Authoritative Parenting (High Responsiveness/High Demand)

The authoritative parent is high on both responsiveness and demandingness. And according to Baumrind, it’s the parenting style that provides the most benefits to kids.

Authoritative parents blend warmth and firmness. They set clear expectations for their children but explain the reasoning behind them. They’ll consistently enforce the rules, but not rigidly. They’re also warm and responsive to their children’s needs while still expecting an age-appropriate level of maturity from them.

In the video game/homework scenario, the authoritative parent would neither give in and let the kid keep playing video games, nor offer a harsh, “Get off now because I said so!” edict. Instead, they would approach their child with something like, “You know the rules. No video games before homework is finished. If you finish your homework now, you can get back to your Fortnite match. If you need some help with your homework, I’m happy to help.”

Kids raised by authoritative parents tend to have the best outcomes. According to Baumrind and subsequent child development researchers, kids raised with authoritative parents have better emotional regulation, perform better academically, become more self-reliant, and have a higher sense of agency than kids reared with other parenting styles.

Parenting Styles Aren’t Boxes — They’re a Flexible Framework

Like a lot of advice based on psychological research, there’s a tendency to treat parenting styles as rigid categories — as if being the “best” parent means consistently maintaining authoritative mode at all times.

The reality is that parents naturally shift between different styles depending on the situation and their kids’ needs.

If your 5-year-old is about to bolt into traffic, a stern, authoritarian “STOP RIGHT NOW!” works better than a warm, reasoned, authoritative explanation about road safety.

Some kids thrive with more nurturing and fewer demands, while others need firmer boundaries. Even the same child needs different approaches through various developmental stages.

The best parents aren’t parenting-style purists. Instead, they’re the ones who can read their child in the moment and respond effectively, even if that means changing their typical parenting approach.

In my 15 years as a dad, I’ve used authoritarian, authoritative, and permissive parenting styles at different times (I don’t think I’ve ever been neglectful). I’ve had my days when I perfectly balance warmth with clear, firm expectations; I’ve also had days when stress and my kids’ petulance pushed me into authoritarian drill sergeant mode.

While I’m not a perfect dad, having the parenting style framework in the back of my mind as I interact with my kids has helped me aim for the authoritative ideal, while adjusting my approach to family life’s ever-changing dynamics.

This article was originally published on The Art of Manliness.

![The Depressing Relevance of ‘The Stepford Wives’ [Horror Queers Podcast]](https://bloody-disgusting.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/Stepford-Wives.jpg)

![‘Superman’ Sneak Features Feisty Krypto And Super Robots [CinemaCon]](https://cdn.theplaylist.net/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/01222722/SupermanFlyingArtic.jpg)

![David Fincher To Direct Brad Pitt In ‘Once Upon A Time In Hollywood’ Sequel Written By Quentin Tarantino [Exclusive]](https://cdn.theplaylist.net/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/31164409/David-Fincher-To-Direct-Brad-Pitt-In-%E2%80%98Once-Upon-A-Time-In-Hollywood-Sequel-Written-By-Quentin-Tarantino-Exclusive.jpg)

![The Weeknd Closes Lionsgate’s More ‘Hunger Games’ And ‘John Wick’ Pitch To Theater Owners [CinemaCon]](https://cdn.theplaylist.net/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/01162058/TheWeekndCinemaCon.jpg)