Inside the (Possibly) Haunted Las Vegas Hotel Where Teddy Roosevelt Stayed

Not the Las Vegas you’re thinking.

I was still stretching out after a six-hour drive when I noticed our hotel for the night was a bit, well, spooky. My mom, sister, and 2-year-old daughter had joined me for a multi-generational road trip from Denver to Santa Fe, New Mexico, in October. Our first stop on the four-day trip was Las Vegas — a town about an hour from Santa Fe that claimed the Vegas name long before the more famous gambling mecca — and we had pre-booked two rooms at the Castañeda Hotel.

The building itself had the expected so-much-history-maybe-it’s-haunted vibe of a place built more than 125 years ago. It was the art that initially set the tone, though. At least for all but the youngest generation on this trip. My daughter couldn’t look away from the painting of a young family standing alone at night in a small dingy surrounded by water, or the one depicting a woman in a nun’s habit walking away from a deserted phone booth in empty grasslands.

Photo: Nickolaus Hines

When I asked the lone receptionist about the backstory of the paintings, he first pointed to a small framed piece of art next to the entrance: a small copy of “A New Year’s Party in Purgatory For Suicides: In which Liberace makes a guest appearance down from heaven just for the hell of it.” It, like the others, was painted by one of the owners, Tina Mion. The description on Mion’s website explains the concept further:

Dante placed those who died by suicide in the second-lowest level of Hell in his Divine Comedy, while Mion puts them in purgatory on New Year’s Eve with reminders of their death. Judy Garland has a pill necklace, while the poet Sylvia Plath wears potholders (Liberace is there because he “just loves a party”). Virginia Wolfe, Jim Morrison, Ernest Hemingway, Jimi Hendrix, Marilyn Monroe, Kurt Cobain, and more join Mion’s friends who died by suicide. Mion, still living, painted herself in as well, blowing a noisemaker in the front row of the purgatory party.

Photo: Nickolaus Hines

Mion’s art can come across as haunting, if not outright haunted. Mion’s work, her website notes, has been used in college classes on “American History and on death and dying.” Paintings in the Castañeda are largely from Mion’s “Momento Mori” (“Remember Death”) series, along with other works from her decades-long career as an artist. That career intersects with another: a decades-long career restoring historic hotels like the Castañeda with her husband Allan Affeldt.

Mion and Affeldt met during a peace walk in Soviet-era Ukraine in 1988. After moving to Los Angeles in the early 1990s, she started a project painting the presidents — a set of paintings that would travel to Presidential museums and eventually lead her to a trip to Africa. When she returned to Affeldt, now her husband, he announced they were buying La Posada, the historic hotel once part of the legendary Fred Harvey Company chain in Winslow, Arizona. They packed up and left on April 1, 1997. Their journey in the historic building hospitality business started here, followed more than a decade later by the two Harvey hotels in Las Vegas: the Plaza and the Castañeda.

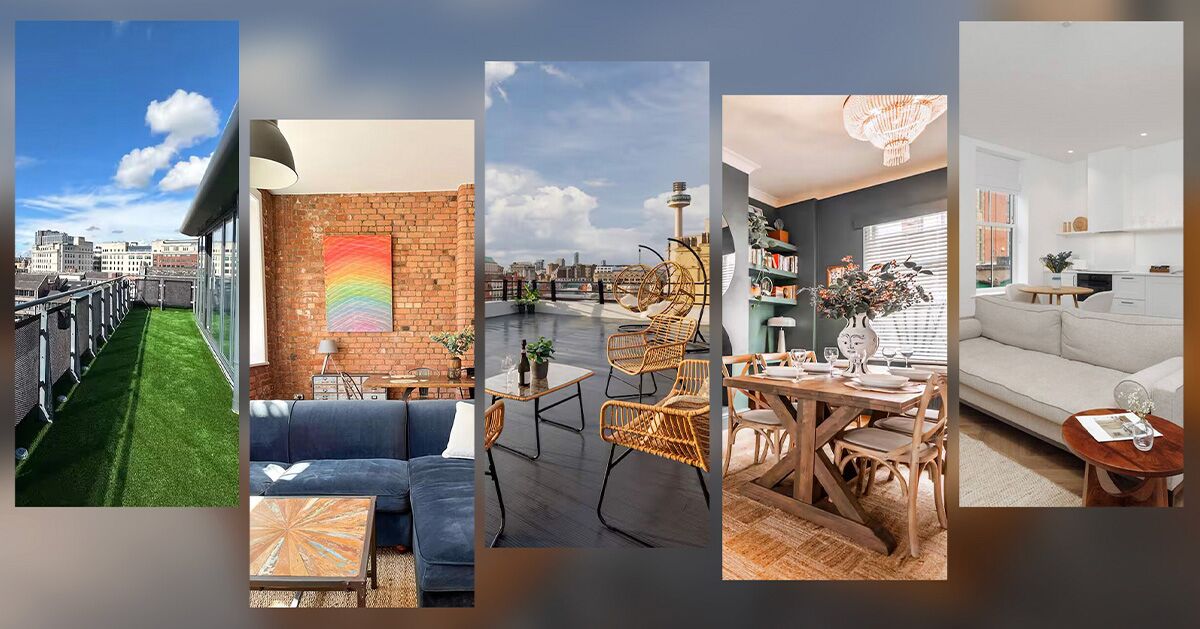

Affeldt and Mion purchased the Castañeda in 2014. “Derelict” is one way to describe the once-cherished building. The hotel closed in 1948, reopened under a new owner for a short period, and then was closed once again and boarded up. (Its bar, on the other hand, had another life where it earned the nickname “Nasty Casty.”) It had sat empty for more than 70 years when Affeldt and Mion took over. In 2018, restoration started with the help of a crew of about 50 locals who got the property into shape to reopen in 2019. The lobby kept its historic atmosphere after heavy repairs, while each room, all named after an historic Fred Harvey site, got major upgrades, Victorian antiques, and art.

The property as seen from the rail-facing side before the restoration. Photo: Underawesternsky/Shutterstock

Bringing the Castañeda back to life was no small task, but worth the effort for the historical significance alone. The original 30,000-square-foot building was completed in 1898 under the direction of architect Frederick Roehrig. It was renowned travel magnate Fred Harvey’s first purpose-built trackside hotel. A wraparound porch fronts the building, while another covered area sits beside the courtyard near the tracks that once brought travelers West by train via the Santa Fe Railway that ran from Chicago to Los Angeles. (Today, it’s a stop on the Amtrak Southwest Chief Line.)

Old black-and-white photos from the hotel’s past show how close the restoration brought the Castañeda to its state in the glory days. The bar, rightfully, is now far from anything that could be called “Nasty Casty.” The Castañeda is in good company as far as preservation is concerned: It sits in a registered historic district filled with 1800s-era buildings. Las Vegas has more than 900 buildings on the National Register of Historic Places, or about one for every 14 residents.

Photos: Nickolaus Hines

The pandemic partially closed the Castañeda shortly after it reopened. A few employees stayed to keep the operation running — film contracts for shows like Amazon’s Outer Range, shot in Las Vegas, meant there was still some business even when most areas of life shut down. Or at least enough people to keep fresh ghost stories coming in.

After we got our keys, my mom gently, but firmly, requested the keys to both rooms so that she could see if everything was okay spirits-wise. (Let’s just say I grew up familiar with the smell of burning sage and the atmosphere of spiritual readings.) I stayed downstairs to chat more with the man at the front desk. He grew up in Las Vegas and helped with the Castañeda reopening, so he’d heard his fair share of stories.

Photo: Nickolaus Hines

In 2014, a crew from the Travel Channel show Ghost Adventures came to investigate and spotted something going down the staircase that led to the rooms. In another case, a musician swore to the receptionist that he heard repeated sounds and old-time music from the room across the hall — that room, and the others next to it, was empty. Many ghost stories revolve around a woman in early 1900s formalwear hovering between the kitchen exit and the staircase. During a slow period at the height of the pandemic, the receptionist heard what sounded like a phone dropping on the second floor. He ran up with a flashlight ready to defend himself, but no one was there.

Photos: Nickolaus Hines

I’m certainly not the type of traveler to seek out allegedly haunted places — especially with a toddler in tow. That said, I do find the stories entertaining and I (mostly) don’t go out of my way to avoid possible confrontations with the supernatural. Stories were thankfully all we got at the Castañeda. The rooms are large and comfortable with a vintage charm, and the location is walkable. It wasn’t until later, when I dug into the non-paranormal history of the property that I found the most interesting stories about what makes the Castañeda special.

The central role Fred Harvey’s Castañeda played in the golden age of rail travel

Railroads made long distance travel easier than ever before in the 19th century, but it was not kind to hungry stomachs. Many trains lacked dining cars, and the few stops trains made were too short for even the unappetizing food available at lackluster lunchrooms not equipped to handle a rush of customers who all had a designated time to order, eat, and pay before rushing back to their train or be left behind.

This was the world before Fred Harvey. Harvey was born in England and moved to New York when he was 15. In 1858, he opened a restaurant in St. Louis that left Harvey broke just a few years later after his partner joined the Confederacy in 1861. He transitioned to the corporate world of rail travel and eventually moved to Leavenworth, Kansas, which became his permanent home town.

It wasn’t until 1876 that he landed on a winning business idea with the Fred Harvey Company.

Harvey struck a handshake deal with the Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe Railroad in 1876 to open the first Harvey House restaurant in Topeka, Kansas. The clean atmosphere, quick service, and quality food — far from givens for people traveling west in those days — was a hit. He added a hotel in 1877 and a hotel-restaurant in 1878. A Harvey business sat at about every 100 miles along the Santa Fe line by the 1880s, and Harvey became known as the “Civilizer of the West.”

The moniker was in no small part thanks to the “Harvey Girls” — young women from the East and Midwest who had to follow high standards in both appearance and social interactions. The women were prohibited from marrying, though they received a wage, free room and board, and relative financial stability for a time when women were largely kept out of the workforce, particularly in the Wild West where merely living in a frontier town could tarnish a woman’s reputation. They were well loved, and even got an MGM musical, The Harvey Girls starring Judy Garland, in 1946.

Among the many properties, the Castañeda stood out for its level of luxury, but also its style. It was the first Harvey property built from the ground up to adhere to the Spanish mission style architecture that’s now synonymous with the Southwest — Las Vegas was once the biggest community in the Southwest and carried a level of influence. The Alvarado Hotel in Albuquerque followed the Castañeda’s design in 1902 (and helped inspire an historic preservation movement in New Mexico when it was demolished in 1970). The Fred Harvey Company portfolio became not just one of the first businesses travelers encountered as they traveled West, they became a defining feature of the Southwest as a whole. That was in no small part thanks to the embrace of the Spanish-influenced architecture that, for Harvey, started with Castañeda.

Harvey died in 1901, not long after the Castañeda opened, and his sons Ford and Byron took over the family business. Trains got faster and took fewer stops through the 1910s and ‘20s. New highways started to become the make-or-break economic driver of towns rather than a rail station. That only got worse after World War II and the start of the international highway system. As highways replaced railroads as the dominant mode of travel, the Fred Harvey Company created a car-focused business with “Indian Detours” that had drivers and guides shuttling travelers in luxury cars to areas they could purchase Native American jewelry, pottery, and crafts.

It was an era of managed decline. Historic Route 66 skipped Las Vegas by a few miles, making it a detour to stay at places like the Castañeda. Some Harvey properties set apart from the rail survived, like El Tovar and Bright Angel near the Grand Canyon and La Fonda in Santa Fe, but most others fell into disrepair and were eventually demolished. The former travel empire crumbled and businesses that once helped shape westward travel were demolished. Today, only a few remain.

Harvey may not be a household name today, even for those who love travel, but he maintains a following. The annual Fred Harvey History Weekend that takes place in Santa Fe, and books out Harvey hotels the hour or so out to Las Vegas as well, is in its 16th year.

An historic site with a presidential past

Teddy Roosevelt riding the train through the Southwest. Photo: Everett Collection/Shutterstock

The Castañeda opened in time to host the first Rough Riders Reunion in 1899, one year after the end of the Spanish-American War. Veterans and Theodore Roosevelt himself, then the governor of New York and two years away from the presidency, arrived by train for a three-day reunion celebration. The volunteer cavalry unit was filled with men from the Southwest. A fancy new hotel in New Mexico where many were from made natural sense for the reunion location.

Newspaper ads for the Rough Rider reunion promoted round-trip train tickets for $26.10 — the equivalent of more than $3,800 today. The event was viewed as a one-year anniversary of the Rough Riders, but also a showcase for New Mexico itself, with Las Vegas at its heart.

Subsequent Rough Rider reunions happened each year in Las Vegas. A photograph from the 1899 event shows a packed crowd gathered to see Roosevelt and the Rough Riders, and other images from the event were in our rooms. These had the standard old-sepia-photo haunted vibe with blurry subjects in certain areas from the camera technology available at the time (probably).

In the modern era, Roosevelt fans are still drawn to history tours in the town, judging by the multiple older couples and groups I saw in the Castañeda lobby dressed in classic tourist gear.

I overheard them talking about what they’d seen and what Roosevelt stops were still upcoming, and I asked a few people if there had been any supernatural Roosevelt-related sightings. Nothing so far, one man said, then lifted the binoculars hanging from his neck and jokingly scanned up the staircase from the check-in desk. But hey, he still had a few nights at the hotel and plenty more places to see. ![]()

![‘Five Nights At Freddy’s 2’ Teaser Revealed & ‘How To Train Your Dragon 2’ Announced For 2027 [CinemaCon]](https://cdn.theplaylist.net/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/02205821/Screenshot-2025-04-02-at-8.57.40-PM.jpg)

![Benecio Del Toro Runs ‘The Phoenician Scheme’ & Emma Stone Gets Shaved In ‘Bugonia’ For Focus Features [CinemaCon]](https://cdn.theplaylist.net/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/02214210/EmmaStoneOscars2025.jpg)

.jpg?width=1920&height=1920&fit=bounds&quality=80&format=jpg&auto=webp#)