Scriptnotes, Episode 679: The Driver’s Seat, Transcript

The original post for this episode can be found here. John August: Hello and welcome. My name is John August, and you’re listening to episode 679 of Scriptnotes, a podcast about screenwriting and things that are interesting to screenwriters. Today on the show, Who’s Behind the Wheel? We’ll discuss point of view and storytelling in […] The post Scriptnotes, Episode 679: The Driver’s Seat, Transcript first appeared on John August.

The original post for this episode can be found here.

John August: Hello and welcome. My name is John August, and you’re listening to episode 679 of Scriptnotes, a podcast about screenwriting and things that are interesting to screenwriters.

Today on the show, Who’s Behind the Wheel? We’ll discuss point of view and storytelling in both film and TV, both on the script and scene level. We’ll also talk about the most dangerous person in the room, plus we’ll answer listener questions on visual effects, syntax, and dealing with clingers.

In our bonus segment for premium members, we’ll explain east side versus west side for non-Angelinos, also known as why Craig and I never see the ocean.

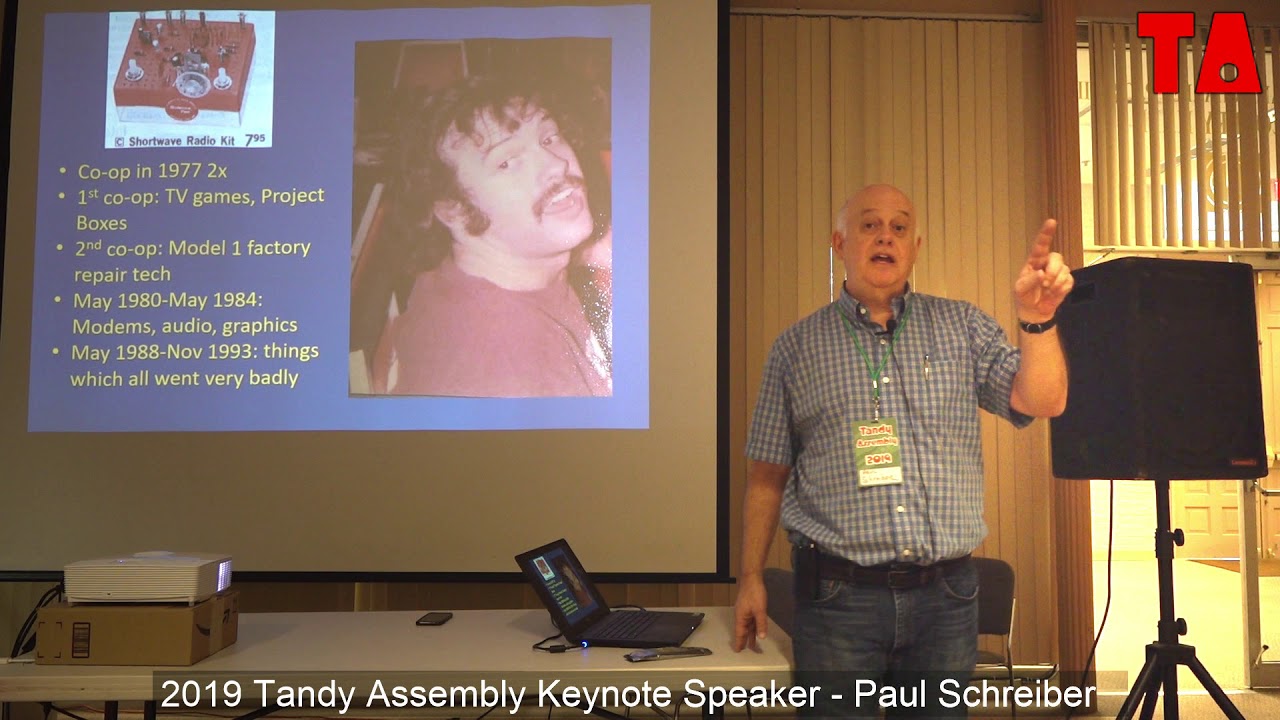

Craig is gone this week, but luckily we welcome back a very special guest. Liz Hannah is a writer, producer, and director whose credits include The Girl from Plainville, The Dropout, Mindhunter, Longshot, and The Post. Welcome back, Liz Hannah.

Liz Hannah: Thank you. Thanks for having me.

John: We’re so excited to see you. We’ve been trying to schedule you for a bit. You’ve been super busy, but this was the week I texted and you got right back to me. I’m so happy to catch up with you.

Liz: Me too. I’m so happy we got it done. I know we’ve been keep trying to do it. 2025, just like 2024, the wheel keeps turning.

John: The wheel does keep turning. We’ve talked a lot about sort of that was weird and unique about 2025 already. We had Dennis Palumbo on to talk through how you try to get creative work done in this strange–

Liz: I loved that episode. I loved that episode.

John: Thank you.

Liz: It was great.

John: Thank you.

Liz: Sorry to interrupt but I feel like I dropped at a time, particularly where I was having the same conversation with so many creative friends, which was what that episode was about so strongly. I hope if you’re listening to this, you’ve already listened to that, but if you haven’t, please listen to that.

John: We had some listeners write in with their reaction to that. One of them is Ryan Knighton, who’s been on the show a couple of different times. Ryan Knighton is a Canadian writer, a blind writer who has traveled a bunch. Drew, read what Ryan had to say.

Drew Marquardt: “Years ago when I was on assignment for a magazine during the Arab Spring in Cairo, I interviewed a number of filmmakers and writers. All of them had stopped working. All of them were in fact quite depressed, they said. They were exhilarated by that political change, unlike the world around us right now, but their depression stemmed from the fact that they didn’t know what work to do. Simply put, they said, ‘How can you make art that refers to a world that no longer exists or is about to disappear? Make art about what?’ Even in positive political change, a similar anxiety, if not paralysis, emerges.”

John: What I thought was so great about Ryan’s point is it’s not just that we’re in this moment that feels so dark and scary. It’s just that we cannot even have a prediction about what the next couple of years will bring. People going through the Arab Spring, they could be really hopeful about the change that was ahead of them, but also they just didn’t understand how to write about the world that was going to be changing so quickly.

Liz: I think that it’s hard to think about what you’re doing on Thursday when this universe is happening, so it’s hard to think about what you could write. I think there’s a paralysis. I also feel like writers are searching for paralysis at times, so like when we have legitimate ones, it’s even doubly hard and surprising. I think that for me, I tend to write in political, social formats often, or worlds, and for me, there’s a paralysis of what should I be saying now.

I think when you’re going through something that feels as traumatic, honestly either positive or negative, there feels a pressure of a response to be valid and somehow parallel to what’s happening and somehow speaking to what’s happening. If you’re not doing that, then it feels defeatist of like, what am I doing with my time? Then I think also for me as a writer, which I know you spoke about on the episode with Dennis Palumbo, but as I’m a writer, what can I do to change the world with everything that’s going on?

You really can. I think that we both serve the roles as entertainers and as we can be mirrors to hold up to the world. We can be reflections on people in power. We can be reflections on where we want the world to go. We can be reflections on how the world is that nobody wants to see. All of that is, there’s a lot of pressure on that to do that well.

John: Because we’re a podcast by writers, largely for writers, it’s very easy to think about it just from our point of view, which is good because no one else is thinking about our point of view. It’s important to remember that there’s also other decision makers out there who are trying to think like, well, what movies should I buy? What movies, TV shows should I greenlight? You’re trying to develop this thing that’s going to come out in two years, three years, like what will even make sense?

One thing I’ve found on recent phone calls and pitches and things like that is if I can talk about things that are universal themes that will make sense, no matter what the world is like, that’s really helpful. One of the projects that I’m hoping to get going ultimately comes down to this moment of unexpected international cooperation to deal with a serious problem. It’s like, oh, that feels universal.

It feels hopeful. It feels like it’s a fraught idea to explore at this moment, but also a thing that you could see working really well for– It’s what we want to sit down in a theater and see. It’s like, oh, a bunch of people coming together and actually solving a problem. I think as we’re thinking about what we as writers are trying to create, we have to be mindful that the people on the other side of that table are also trying to figure out what the heck is going to make sense as these shows and these movies come out.

Liz: I don’t think it’s one-to-one, but I personally feel like I have to tread a little bit in hope right now. I am finding that to be a constant word that comes up in conversations with executives and conversations with buyers is we need to have something hopeful that can be revolutionary, that can be not. But I think something that isn’t living in the darkness that we are living in just by waking up and turning on the news, I feel like finding a way out of that is both universal, as you’re saying, and also something that we can always hold on to and the only thing we can hold on to right now.

John: I was listening to this Culture Gapfest this morning, and they were talking about an article and trying to differentiate optimism from social hope and the idea of optimism feels a little naive and it can feel self-defeating. I was like, “You’re ignoring the world around you.” Social hope is remembering that people can come together to actually achieve things when they need to. There’s reasons to still have hope even in dark moments and it’s a thing we need to kindle as writers, but also as parents. I think it just is making sure that you’re able to be developmentally appropriately honest with your kids about this moment that we’re in, but also how people come together to resolve these issues.

Liz: Yes, I have a three-year-old and so living through the past six months has been just very strange and seeing his community of other three-year-olds and how each of them really is developmentally different in terms of how much they’re perceiving of what’s happening and how much they’re not. My son, fortunately, is very deep into cars right now and cars are fine, so that’s great for him. We’ve been living in that world. Lightning McQueen, A-plus over here. I would love to talk about Cars 2 with somebody, just like really want to break that down.

Then other kids are really understanding it and really they understand who Donald Trump is. They know who Kamala Harris is. They understood what the election was, at least peripherally in terms of how it affected their universe and the world. It’s really hard, as you said, to balance being a parent and how you appropriately have that conversation with a three-year-old, a five-year-old, an 18-year-old, and how you balance that with yourself.

I think, as a writer, I have found myself paralyzed with what’s happening in the world, both with the pressure of how I feel I can respond and also just how, as a parent, I can function and raise him. The thing that I continue to go back to is hope, and I think it’s really important to differentiate that from being naive about just, oh, it’ll all be fine. Hope doesn’t come without parameters that are, we’ll have to do a lot of work to get to the place that we can be hopeful for. Part of that is working.

When I wrote The Post, I’d been writing that movie for a long time, and it just so happened to come out in the era of Donald Trump, and I sold it right before the election in 2016. That’s the thing I’d say to writers who are looking for a way to respond, is tell the story that’s in you. It will always be relevant if it is something that you find relevant to your path and your existence.

John: Absolutely. Now you’re working on The Post 2, the Bezos era, and it’s going to be great. It’s going to be fantastic. Just so much better. All those dilemmas of Katharine Graham and all the things, now the problems are solved.

Liz: Yes. We fixed it all in 1971.

John: We did it, team. Another bit of follow-up, that same episode with Dennis Palumbo, we answered a listener question about a listener who was comparing themselves to the Pixar brain trust, and feeling like, well, I’ll never be able to do as well as the Pixar brain trust. Drew, what did Scott have to say?

Drew: Scott said, “My framing of this is to think of it this way. I need to write a spec script so good that really talented people would read it and want to work with me on the project. It’s still a high bar, but it’s not as daunting as saying you have to write something as good as Toy Story all by your lonesome.”

John: All right. I think that’s fair. We talk about writing a script as like, this is the plan for making the movie, but it’s also a document that shows how good of a writer you are, and that hopefully, people will want to invite you into a room to do things. Liz, you started as a feature writer, but you also worked in rooms with other writers, and you start to realize like, oh, we are smarter together than any one of us is individually.

Liz: Yes. I think there are at least two things to that. One, I completely agree about a script being a document. I don’t write novels because I want to write a screenplay that becomes a visual piece. In that, there are thousands more of collaborators, but you as the screenwriter, your draft of the screenplay, that goes, be it a spec or be it your working draft that gets a director attached or whatever it is, that’s like your metal that you can show and that’s your proof of concept of yourself as a writer. I think it’s important while difficult to compartmentalize the steps and the successes that are possible at every stage of a screenplay. I wrote The Post as a spec to get representation and to have a career.

I did not write it because I thought it would get made. I’ve said it many times, but it was– it’s a moral thriller where the two leads are in their ’50s, no one kisses, there is not an ounce of sex in it, and truly the piece of the puzzle is solved within the first six minutes of the movie and then the rest is just like, do we do it or not? I wanted to watch it and I wanted to make it and so that’s why I wrote it. The screenplay changed my life, then the movie changed my life, but there were very significantly different stages of that one was involved with the screenplay.

The other thing I’ll say is that absolutely working in a room, it’s always better to have more brains than one, in my opinion. They have to be the right brains. They’re not always the right brains. That’s the thing about a room that is complex is sure. There are showrunners I know who’ve had dozens of rooms and their rooms are nearly perfect at this point because you’re working with the same brain trust that you have cultivated over the course of your career. That doesn’t always happen and it doesn’t happen often early and I think it’s trial and error, but when you get that room that fits perfectly for you and for what you’re doing, then yes, it’s great.

John: We’ll put a link in the show notes to the episode that you were on with Liz Meriwether talking through your experiences on those rooms and it became so clear that how you cast those rooms, how you put those rooms together makes all the difference in the ability to achieve a vision. You can still have a singular vision of that showrunner, that creator, but they have help.

The original listener who wrote in with that question was like, all right, I’ll never be as good as a Pixar brain trust. It’s like, yes, but you get to be part of that Pixar brain trust by showing what you can do and by allowing yourself to be part of that community. It’s also the very understandable sin of confusing your first work with someone’s finished thing and the way that we– if we went back and looked at early drafts of things based on what they became, you see the transformation that the process itself brings out.

Liz: It’s also, calling it a brain trust, I feel like simplifies it almost. It’s more of like a full body that has been completed because you have one person who’s a really good right arm. You have one person who’s a really good left brain. You have specialties within that “brain trust” that are specific and going to exactly what you just said, like knowing your strengths and showing those strengths on the page gets you to be the right arm in that room rather than thinking that you can accomplish the entire personage that is the writer’s room of a Pixar movie, which by the way has multiple iterations throughout the life of a Pixar movie. This isn’t the same four people for 10 years.

John: If people want to go back and listen to the deep dive we did on Frozen, they had a plan for that movie and well into the process as they were watching it on the screen like, “Oh no, this is not right.” Then it was coming in and recognizing, “Here’s what’s working, here’s what’s not working. How do we steer towards the part of the movie that it wants to be?” That’s also part of the process. It’s the thing we don’t see as often in feature films, but in TV as we’re back in the old days when you were shooting episode by episode, you’re finding episode by episode.

Now that we do things more as a block, you have to really then take a gestalt look at the whole project and figure out, okay, where are we at? Where are we getting to? That’s actually one of the main things we’ll talk about today in the episode is really point of view and perspective and storytelling power. That’s the thing you discover in the process, whether that process is a long movie development or episode by episode or breaking the whole thing as a room. That’s part of the journey. It’s part of the discovery and you have to be open to that as a reality of writing.

Liz: I’m not sure if you talked about this on that episode because I, unfortunately, missed it, but there’s also an amazing six-part documentary about Frozen 2, which is on Disney+, which comes in towards the end of the– They don’t have a ton of the feedback of it, but they do have that, they don’t know what the main song is going to be. They walk you through all the animation process. It’s amazing. I really recommend it, particularly if you think that any one person or any six people do it on their own at Pixar or Disney Animation, you’re very mistaken.

John: That’s great. Back in episode 652, we were talking with a playwright who was having trouble adapting their work to film and Tony wrote some feedback on that.

Drew: Tony says, “Craig touches on it in the beginning when he says that plays are inside and movies are outside, but I would take it a step further relating a similar comparison that was shared with me, that plays are driven by what people say to each other while movies are driven by what people do.”

John: I like that as a distinction. Plays are mostly talking. They really are. It’s about the verbal fights and spars and [unintelligible 00:15:28] we have between those characters and movies, we see people doing things. I think that originates with the fact that movies are brutal. Fundamentally a visual medium that sound came later. We tell stories through pictures on the screen.

Liz: I think that’s great. We’re going to talk about it, but I think that POV in general is an interesting distinction between film and television and plays and that doesn’t mean that you can’t have privileged POV in plays, but I think it’s really specifically different because of the visual aspects, the visual tools and technical tools that you have in features in television, but I like that. I think that’s a great distinction.

John: Yes, I like it. A phrase that Craig and I have discussed often on the podcast is begs the question, which does not mean invites the question. It really, it’s a legal term that means circular reasoning and things like that. I saw a piece by Alex Kirshner this week where he said begets the question, which I think is a clever way to use the framework of begs the question, but actually have it make sense.

Begets the question, it causes us to think of the question of this next thing. If you are reaching for begs the question, maybe add an ET in there and make it begets the question and maybe that’s how we’ll get through this annoying thing where begs the question has come to mean something it was not originally meant to mean.

Liz: Love that.

John: Love it.

Liz: I love being a trendsetter too, so I’m going to start using that and people will be like, “Whoa, where’d that come from?”

John: Absolutely. Begets the question.

I was talking with a friend at dinner this last week and he works on government contracts. He doesn’t work for the government, but he works on government contracts and he was told that they are supposed to remove all their pronouns from their email footers because of Musk and Trump and everybody else, which is nuts. I just want to have a small moment to rail against this because here is like, even if you believe in that woke-ism and all these things have to go away, pronouns are so effing useful.

It’s so nice to see if there’s a name, I don’t know, or if it’s a Chris or a Robin, to know whether it’s a he or her or who am I talking to is so useful. There’s this expectation that all names we can automatically understand the gender of, we simply can’t. I would just encourage people to put that in their email footer just so everyone knows, so that if it’s– Particularly if it’s a Chinese person is looking at this, they understand like, oh, I’m talking to a man versus a woman. I think it’s just ridiculous. I say, please keep putting your pronouns there. I think it’s useful.

Liz: Yes. Also, there are so many things to be concerned about in this world. There are so many legitimate problems. The idea that this government is attacking existence and attacking things that are not hurting people, like putting your pronouns in your emails, which of course is a tangent of attacking trans rights and the queer community. We’re smarter than you, we see what you’re doing. It’s just so beyond infuriating to me that I don’t actually have an articulate thing to say other than how petty and small and bored must you be that these are the things that you’re attacking.

John: My case I’m trying to make is that in addition to being helpful for a group of marginalized people, it’s just helpful for everybody.

Liz: Yes, I agree.

John: It’s just so damn useful. It’s like a small innovation that was just incredibly helpful. To take it away because you’re worried about the political valence of it is dumb.

Liz: It’s all dumb, yes.

John: It’s just my small rant on a topic. On more happy, positive news, this last week we launched Highland Pro. It’s now in the Mac and iOS app stores. It went great. We were a little bit nervous. We did a soft launch in Australia just to make sure that it would actually work properly and that people could subscribe to it. It’s worked really great.

Thank you to everybody who wrote in with the comments to Drew. Drew’s been sorting through the mailbox. Thank you to everyone who left a review. That is super helpful. Liz, I sent you a copy. I don’t know if you had a chance to play with it yet.

Liz: No, I am in a deep, dark place of not writing right now. When I do write, I will. This is why your podcast two weeks ago was very helpful. No, I’m currently in a like, carding, and Google document phase. That’s where I’m at.

John: That’s great.

Liz: I love Highland. I’m so excited. Can I shout out my favorite edition or my favorite aspect of this? Because it’s insane that we haven’t created this. I’m sorry for not knowing exact way that you do it. I always call it a scratch pile or like I have a different file draft document where I put things in there where I don’t want to get rid of them but like I don’t want them in this draft and I always have two documents and it’s always annoying because you’re like, where is this? You guys have created just a place that you can put it for every document.

John: It’s just a shelf.

Liz: It’s just the shelf where you put it.

John: The shelf [unintelligible 00:20:23]

Liz: I saw this in the program and I was like, this is great. This is so useful. It’s just there’s a lot of common sense things which is not dismissive but there are common sense aspects to Highlands that I’m very appreciative of that shouldn’t be hard to be in there for writers.

John: Absolutely. We’re excited to have it out there in the world. I’m excited for people to copy things from it because the other apps will do the things we do which is great because it makes the world better for other people too. Fantastic. If you want to try it, it’s on the Mac App Store. It’s on the iOS App Store. You can just go to “apps.com” and see more stuff there. You can see a little video of me talking about it. In fact, if you want to see, it will throw people because so many people when they meet me in person like, “Oh wait, I wasn’t expecting your voice to come out of that face.” You’ll see my face. You’ll see me talking there and see how it all fits in person.

Let’s get to our marquee topic. This is about the driver’s seat. This is something that occurred to me this last week. I was watching two series that I really enjoy. Severance and The White Lotus. I was thinking about which characters in those series were allowed to drive episodes, which characters were allowed to drive scenes by themselves. We’ve talked about this on the show before, but mostly from the context of features. In features, very early on, you established the rules for the audience, the social contract of like, these are characters who can drive scenes and these are characters who can be in scenes but not drive them themselves.

We’ve talked through issues even in the first three pages where we’re confused from whose point of view we’re telling a story. Liz, as somebody who has done more episodic work, I feel like those are some fundamental choices that you are making early on in the pilot, but also in those rooms. And you have the opportunity to bend or break those rules as you go through a season, as you’re figuring out episode by episode. Talk to us about what you think of when you think of the driver’s seat or point of view or even some other terms that you might be using when you’re referring to this phenomenon.

Liz: I think point of view, an episode protagonist is something that we use a lot. I am actually, breaking a series right now and point of view is incredibly important to the storytelling of it and there are a number of point-of-view characters within it. My partner and I, after we sold the show and we were like, let’s sit down and really think about what we want to say, how we want to say it. The how you want to say it is what characters do you want to say it.

That for me is a day one conversation because I can’t really start to break story without knowing who is going to be telling that story to an audience and who I’m going to be trusting with that story and who my audience is going to be trusting. By the way, that might be a trick, right? When you have a point of view character, it’s always privileged storytelling because they are not just a narrator telling you what’s happening. They are telling it through the lens of them as it is also a character revolving in the story. I think it’s really for me fundamental.

On Plainville, we had a lot of point-of-view characters because we had three timelines and we had a central thesis which I think does begin to adjust how you have these conversations which was, what if everyone was involved in this? It was a challenge to ourselves which is, what if we step back and don’t take a black-and-white perspective on this and say she’s the villain, he’s the victim?

Let’s look at everybody in a three-dimensional way and once we start doing that and telling that story of how these two people ended up here and their families ended up here, what are the scenes that come out of that story that feel organic and then who are the storytellers of those scenes? Lynn was always a primary storyteller, Coco’s mother, both because of her own trauma and her own journey but also because there were stories to be told about him that should come from her and shouldn’t necessarily have come from him because you are your own main character of your own life.

I think it’s really important. I think that happens organically in any series and should happen organically at the top because, in my opinion, you don’t know what story you’re telling until who’s telling it. That goes for features or television. I think of Severance in particular, now you’re adding another layer to this which is the privileged storytelling. Which is, you as the filmmaker are withholding very significant beats from the audience and you’re probably feeding incorrect or–

John: Misdirections, at least.

Liz: Yes, misdirections to the audience that you also don’t want the audience to be upset about. You don’t want an audience to feel betrayed by those misdirections. You don’t want the audience to feel betrayed by your storytelling techniques, but you do want them to be surprised. I think the crafting of that is a whole other level that I’m sure begins with what we were just talking about, which is who are my storytellers? Then also, at what point do I start to lie or misdirect?

John: I want to separate those two ideas out a little bit. There’s who has storytelling power and within the world of the stories or who do we get to drive things? Then also, really the social contract you’re making with the audience about not just who’s telling the story, but to what degree you as the creator of the show, as the show itself, is allowed to misdirect and do a magic trick on the audience.

Let’s start with the first part because one of the things you said that I thought was so interesting is you talked about storytelling power. You mentioned narration, and most series are never going to have narration. You’re not going to hear the person’s inner thoughts. That’s actually a useful way of thinking about who can drive a scene. Could that person literally have a voiceover?

Would it make sense for that character to talk directly to the audience? If it is, then they clearly have storytelling power. They can actually speak directly to the audience. In Big Fish, the movie, both Edward Bloom and Will Bloom can speak directly to the audience. You hear them talking directly to the audience. That choice I had to make in those first 10 pages to let it know both of these people can talk directly into your ears.

In most series, most movies, you’re not going to have that, but the equivalent of that is who is driving a scene by themselves? Who is the person who the scene doesn’t start until they enter the room? Those are fundamental choices. As you’re thinking about that on a series level, you might say, “Oh, we need to know what’s happening with Jane and Bob in this whole thing.” But if neither of those characters has been established in a way that we can expect to see them in a scene by themselves, that’s going to feel weird.

Those are the reasons why you can’t cut to are you a show that will cut to the random security guard and his conversation with somebody or not? Those are big choices you need to make early on. You can have fun with it at times. I can think about in The Mandalorian, they’ll cut to a conversation between two faceless guards who are having a little conversation, but it’s always in service of the bigger storyline. You’re not going to keep coming back to them as a runner.

Liz: I think there’s also the question of if you have to know what’s happening with Steve and Jane, but you’ve never established them as POV characters, then do you really need to know what’s happening with them? Because I think that it can become overwhelming sometimes, particularly when you’re starting out as a feature writer or as a television writer of I have to tell everyone’s story.

This is the other thing going back to the difference between plays and feature and television. In plays, you have a set cast, and you can only have so many people there, and you can only tell so many stories within that set cast. With television, in particular, it can be endless. You can continue to add cast as the episodes go on, and many shows do. Is the story that you’re telling with that cast member, that character, important to the story that you’re telling overall?

Which is why I do think it’s really important to come down to theme and come down to, as a creator, as a storyteller, what is it that you want to say, and what do you want to have your audience leave with. We always talk about blue sky in the writer’s room, which is that first two weeks, which is so lovely when you get to just sit with the writers and talk about what you want to have happen. It’s big dreams and there’s no bad answers and there’s no wrong answers. That all comes later.

For me, by the end of that week or two weeks, I want to know what the show is that we’re making. What are we collectively saying, and what are we all on board to collectively say? On The Dropout, we had a lot of conversations about her, about Elizabeth Holmes, and about the characterization of her within the series. What did we want to say, and how did we want to say it?

There was a lot of perspectives about her, in particular, at the time, and so a lot of our conversations were pushing that out and coming with our own bias to the table and then talking about that bias. Similar with Michelle Carter in Plainville, was a lot of people having a bias towards her, and that’s fine. I don’t think everybody should have the same opinion. That’s important. Again, when you talk about the brain trust, it’s important for not everybody to agree.

John: Let’s talk about Elizabeth Holmes. Clearly, she’s the centerpiece of the story, and she does protagonate over the course of it. We see her grow and change over the course of it, but if you’d locked into her POV exclusively for the entire run of the series, it would have been exhausting, and you really would have had a very hard time understanding what anybody else was doing, because she’s mostly for better, for dramatic purposes. She is, I don’t know if you want to say a narcissist, but she is, she’s really at the center of all this stuff, and she herself does not have a lot of insight into the people around her. You needed to be able to establish early on that we’d have scenes that were not centered upon her and understand what was going on around her.

Liz: I think she’s quite unempathetic, and just, if you’d never watched The Dropout and you only watched the documentary or listened to the podcast, it’s very hard to empathize with Elizabeth Holmes. Part of our goal was to infuse some empathy into her character, and I think empathy is the important word here. I don’t want anybody to sympathize with her. I think she’s quite hard to sympathize with. Empathize in terms of, can you put yourself in her shoes and see it from her perspective for a moment within the series? It doesn’t have to be the entirety of the series, but can you take a step back for a moment and not just go, whew, that monster, and find yourself into it that way? That was really important for us.

Then I think a word we continue to use, protagonist, which I think is important rather than hero of the story because the heroes of that story were not Elizabeth Holmes. The heroes of that story were other true people who worked at Theranos, as well as people who were just the day-to-day people who were completely affected by that. They are the heroes of their own stories, as well as this one as a whole. I think it’s important to remember when you’re trying to break out your point of view characters, they don’t have to be the hero of the story, they don’t have to be the villain of the story, but they are often the protagonist of the story.

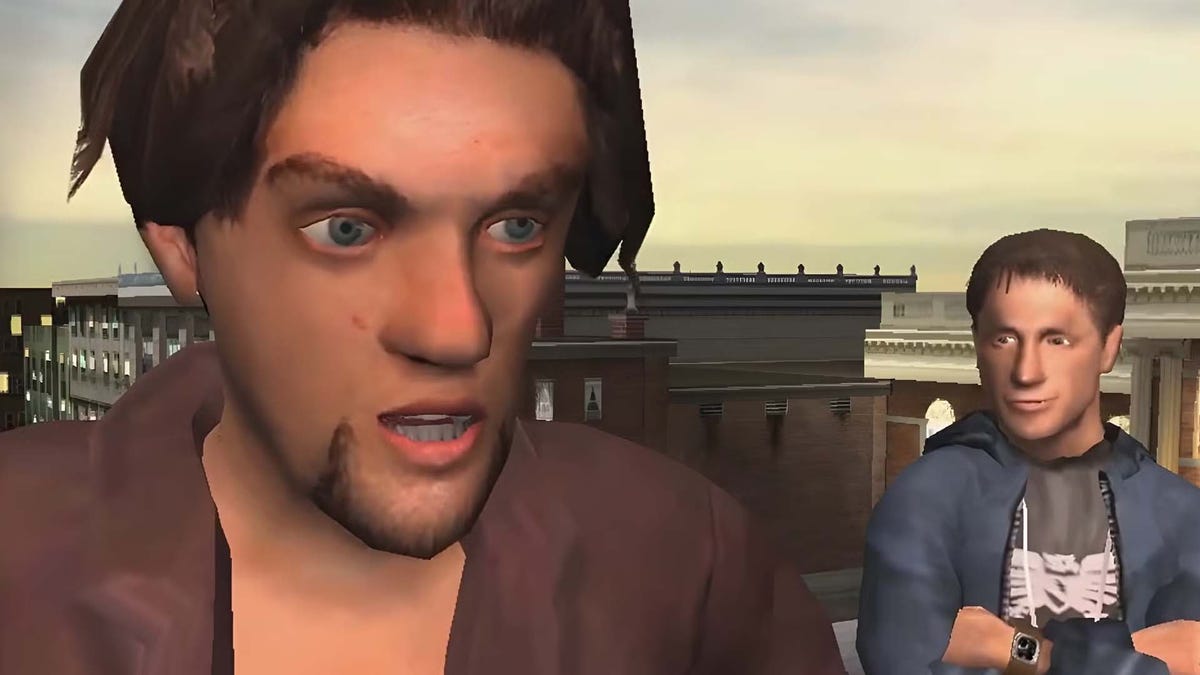

John: I want to talk about protagonists as it relates to a recent episode of Severance. Again, we will not do any spoilers here, but in the second season, there’s an episode that is largely from the point of view of a minor character, a character whose name we knew but had never had storytelling power, and suddenly it’s all centered around her, and Mark, who is clearly the hero of the story, clearly a point of view character.

What I found interesting as I was watching, I thought it was fantastic, and I wondered as it finished, “Wait, did anything actually happen, or were we just filling in backstory?” Then I was like, “Oh, no. She really was the protagonist of the story.” She was the one who came into this episode with a need, a want, a desire, and was trying to do it, and we saw her in every moment trying to create some agency for herself to be able to affect the change that she wanted to affect.

The episode had a very classical beginning, middle, and end of a character who was trying to achieve one aim in this episode, which is good classic TV. At the same time was intercutting to show you all the history that led up to the moments that we were at. I thought it was an incredibly good episode, but also a really good reminder of the attention and craft required to both move the ball forward as a series while still having stakes and development and progress within an episode.

Liz: I have not watched that episode.

John: Hopefully my vagueness is useful.

Liz: No, it’s great. I think I do know who it is, and if I don’t, it still brings me to the same point, which is, I think that you have those conversations in the writer’s room when you begin to talk about that character very early on. Which is, I would imagine that in season one or in season two, whenever that character is first mentioned or introduced, You probably, as a showrunner, have in the back of your head, I really would like to see the perspective of this character of what is happening or of a separate story. I want to know more about this character because it affects your casting.

It affects your conversations of, okay, so if we are going to see a privileged point of view of that character at some point, how is that affecting the characters we’re seeing on screen now? I love when television shows do that in good ways, in successful ways, because it can both fill in the blanks on some things, but more importantly, you can think that a story is contained in a box and you realize that the box is open. Now there are things that you had no idea to be curious about that now you’re curious about, so it can change your perception of the series.

John: A term we’ve used a couple times here is privileged storytelling, and I’d love to unpack that because I’m hearing that to mean it is the special relationship of the show to certain characters or how we as an audience also understand that the show is not telling us everything.

Liz: I think it’s that. I think it’s two things, so we’ll just complicate it even more. I think it’s yes, that, and then I also think that it is a privileged storytelling of a character’s inner life that the rest of the characters are not privy to. For instance, with Mark in Severance, from the pilot, we know, as the audience, more about him than he does, because he obviously is severed. There is privileged storytelling in two ways, that I think is, in Severance in particular, exceptionally well done, and at a very high level, that would drive me insane.

For instance, on The Dropout, it was privileged for the audience to know that the box didn’t work. Because we knew that, she knew that, but not everybody within the series knew that. In Plainville, we knew that Coco and Michelle’s relationship was not what Michelle was telling everybody that it was, but they don’t know that. I think it’s important to distinguish as a writer and as a storyteller, what information everybody has, why they have it, and if the audience has it as well, how that changes their perception of what is coming next.

John: This is what is so complicated about writing, is that we have to be able to both be the architects who know why everything is there and how it all fits together, and we know if we have perfect insight to everything, and be able to step outside and say, okay, from the artist’s point of view, where are we at, how much do we know? In a case like Severance, where we have so much more information than the characters themselves know, and we have to be looking at Adam Scott’s characters like, this is this version of Adam Scott who wouldn’t know this other thing, and how is this all tracking?

It’s complicated, but I think that’s honestly the excitement and the reward of it. It’s so difficult to do on a writing point of view, but it can be so satisfying when it works well from an audience’s point of view because it’s requiring us to use our brains in interesting ways that are actually natural to how we are built to function. I think we have this inherent desire to understand other people’s motivations because it’s a useful survival mechanism for us, and it’s engaging all those things in our brains.

Liz: The only thing I would add to that is my own personal opinion, at least as how I come from a writer and as a viewer, which is the actual events of any story, but we’ll take Severance. If you gave me a five-page document that told me everything that we’re getting to and what’s happened, it just won’t be that interesting. It just won’t. It will never be that interesting.

What is interesting is how each character unfolds the story in front of them, how each turn happens, how I’m allowed to participate in each turn, and how the information is interpreted both by me and the people on the show and the people that I talk to about the show. So I think it’s important, at least for me, to always come character first when we’re talking about point of view and come from character first of empathy and character first of journey. For instance, is the story of Watergate most interestingly told through Nixon’s point of view or from the two journalists who fought for a year to break that story?

When you start even at the very beginning, for me, with the Pentagon Papers, is the most interesting version of this to tell the story of how the New York Times got the Pentagon Papers, potentially, is the most interesting version for me, Katharine Graham, and that it’s actually about her becoming the publisher of The Post and having her coming-of-age moment, that’s more interesting to me, and that’s the point of view in which I’m telling that story.

John: This is a reminder that after 679 episodes of this series, it always does come back to the fact that storytelling is not about the what, it’s about the how. It’s how you tell the story makes all the difference. Point of view, driver’s seat, who’s in control of telling the story is one of those fundamental how decisions that you need to make early on. If you made the wrong choice, well then go back and rethink it from another point of view. The reason why Liz is doing all this work on notecards this week is because she’s figuring out the how before she starts putting pen to paper.

Liz: Also, it’s really hard to write.

John: You’re avoiding writing.

[laughter]

Liz: Writing is hard.

John: Writing is hard. Let’s switch to something that’s a little less crafty and more the business that we’re in. This was a thread by Todd Alcott this last week where he was talking about– he was actually referring to some political events, but I really liked his description of what he saw in Hollywood all the time. He’s talking about the stranger in the room. Drew, if you could just read through– It’s not the whole thread, but something that will link to the full thread, but read through what Todd was describing about the stranger in the room.

Drew: “Screenwriters especially are well aware of the role of the stranger in the room. The stranger in the room is anyone in the meeting who is just there as a friend, someone who has no creative authority on and no stake in the project being discussed, anyone in the room who is a last-minute addition. Sometimes it’s a 20-something intern, sometimes it’s an executive from a sister office, sometimes it’s someone from marketing, or sometimes it’s an older, more experienced producer who’s lending a hand for a day.

The purpose of the stranger in the room is to destroy the project. The stranger in the room is the one who, after the writer and producer, and director have all agreed on the direction of the story, says, ‘Well, how will that play in China?’ Or, ‘This sounds a lot like whatever movie,” or, “But isn’t this movie really about love?” Then, suddenly, the balance in the room shifts. Suddenly, a collaboration, a negotiation, as it were, becomes an argument, where, just moments earlier, everyone was agreeing on how awesome the project sounded. Now, suddenly, the creatives are on one side, the suits are on the other, and the meeting becomes a power struggle, one the creatives can only lose because the suits have the money and the creatives only have the art.

John: Oh, this gave me such terrible flashbacks because I’ve been in those rooms where like, “Oh, wait, who’s that person? Who’s that?” Things are going well, and they ask questions, and they just start pulling threads. Creative challenging is fantastic if you’re poking at that thing, but then you realize like, “No, no, you’re here to destroy this. You are here to sink this ship.” At least three or four times in my career, I can really point to like, “Oh, this was a trap. This was a setup. This was meant to ruin a thing.” So I want to acknowledge this. I’m not sure I have specific solutions for it or guidance for it.

Liz: I’m breaking into a sweat having this conversation, legitimately.

John: This has happened to you.

Liz: Yes, I’ve never heard the phrase, “Stranger in the room.”

John: No, neither have I.

Liz: Maybe that’s terrifying me because now I’m putting pieces together through my career. Creative conversation, creative conflicts, creative pushing is always good at the appropriate time. I think what this is we’ve already gotten past these 12 hurdles, and now this person is like, “Let’s go back to Hurdle 1, and let’s start talking about that,” or, “Let’s go back to Hurdle 6, and let’s talk about that.”

It’s funny, out of nowhere today, maybe because I had read the rundown for the show and was thinking about this, and sort of like, “That never happened to me,” and then now I’m sweating. I was thinking about this one experience I had making a movie. We were on set. It was an indie. We were trying to figure out how to make this movie for no money and all of that. The director had called me the night before and pitched to me how we could save some days or things like that. He had pitched to me an idea of losing this one scene.

The knee-jerk reaction for any writer is like, “No, every scene’s important.” Then I thought about it and I was like, “Well, maybe we could move the content of the scene to someplace else.” Particularly as a writer on set, your job is the problem solver. Your job is to maintain the integrity of the show or the feature while making it producible. I was like, “Yes, I think we can do that.”

Then the next day I went into a meeting and one of the collaborators on the project was like, “Oh no, we absolutely can’t do that,” and really pulled it back. Then we went backwards in time to going to why this scene existed and all of this. I sort of was like, “If I’m the writer and I can say we can lose this scene, then we should probably move on from this argument.” We didn’t, and we continued to have it until we still lost that scene.

I promise there’s an end to this, which is I generally find the stranger in the room as they’re saying whatever they’re saying purely out of ego and purely out of the need for their voice to be heard. I don’t generally believe that it is for the goodness of the project. That doesn’t mean that it can’t be, but if you are the stranger in the room, and you are saying something like this, you know that it’s not positive, you know that it won’t end well. There’s no other reason for that to be said other than, “I want to be heard, and I need you to hear me.”

That goes to my advice, which is hear them. Let them be heard. Acknowledge whatever feelings are being felt by everybody and whatever threads are being pulled on. Then get off of the call as fast as humanly possible and never talk about it again.

John: Yes. It’s lovely that it could be in a call. I’ve had this happen in person twice. One case was the executive. Literally, we were like weeks away from shooting. I was like, “Listen, I think it would be best if we went back to cards and really thought about this.” I’m like, “Oh, no, no, no, no, We’re not going back to cards. This is not a fundamental situation.”

Another meeting where I was on my polished step and this producer asked me basically a fundamental POV question. It’s like, “Well, what if it wasn’t about this, but it was about this other thing instead?” I was like, “Where do you think we’re at?” In both those situations, I extricated myself as well as I could from that situation.

Liz, what I think you bring up, which is so insightful, sometimes I’ve been the stranger in the room, I’ve tried to be really mindful of, “Listen, I see a fundamental problem here. How do I both acknowledge the fundamental problem and help steer people correctly without just blowing the whole thing up?” I think that is a delicate art too. It’s really making clear, within the reality of the space you’re in, what is the most work or the best work that could be done to get people to the next place.

If I truly feel like, “You need to stop this,” or, “You need to kill this,” I will always do that in a one-on-one and not in a group situation. Because I think it’s the group situation, the social dynamics of it that make it so awful. It’s like, you’re around a set of people who are seeing these things. If it was just a one-on-one conversation, it wouldn’t happen.

Liz: Yes, my scenario was also in person. I also, just as a human, don’t tend to react well in person to these scenarios because I’m just like, “Why are we having this conversation? We’ve already done this. There’s really big fish to fry, this isn’t one of them.” I think you bring up a bunch of really good points, one of which is that sometimes there is something true behind it, and though it means more work, or fundamental work that seems to have been accomplished, there might be some truth to the note.

To be clear, I think it’s important to always look at each note as if there is truth behind it. I do not believe in dismissing notes. One of your episodes, which I send to people, which is, “How to Give Notes to Writers,” which is one of the most foundational podcast episodes that anyone working in this business should listen to, because so much about this is about presentation, both from writers receiving notes and people giving notes. That process can immediately taint whatever the note is very quickly and very easily.

Look, we are sensitive, sweet, often thin-skinned people in this industry who don’t like to be wrong. That doesn’t always make for the best amount of collaboration when it gets to that stage where you are so close to the end. I think it’s important to really look at who the note’s coming from, how the note is coming to you, and process that in whatever way that you have to process it to hear the note.

I also really go back to something that Christopher McQuarrie said, which is, I’m going to butcher, but it’s something I think about a lot, which is, “There is no bad note.” There is no such thing as a bad note. There is such thing as a poorly given note, but there’s no such thing as a bad note. Because if you’re getting noted on something, it just means you’re not doing your job as a writer. You’re either not doing your job by how you’re telling the story, you’re either not doing your job of the point of view, or you’re not doing your job selling it.

That, for me, really changed my way of hearing notes and hearing the way in which I should think about them. I also want to say, that doesn’t mean you’re a take-every-note, but it means that you need to consider why it’s being given to you.

John: Yes. One of the things about Todd’s thread that really resonated for me is that the person who was coming in to do this job really had no stake in it or didn’t have the most immediate stakes. I wanted to differentiate that person from a questioner. Questioners can be just incredibly annoying. There’ll be directors, or producers, or actors, who will just want to have a three-hour meeting where they pull everything apart, and it’s just part of their process in how they figure out stuff. It’s so annoying. As a writer, it can be torture.

You see, “Okay, there’s an end product, there’s a reason why we’re doing this,” and you just have to put up with it and live in that space with it. Sometimes good things will come out of it, sometimes it gets to be frustrating. You understand, they are making a genuine effort to make this fit right into their brain, and that’s a valid process. It’s the stranger in the room, it’s the person who’s just there to be an assassin, whether they know it or not. They’re there as an excuse for killing a thing or for destroying a thing.

I think if you’re going into a meeting, this is some practical advice here, try to know who’s supposed to be in the meeting. If someone shows up who’s not supposed to be in that meeting, your spider sense should tingle a little bit just to make sure you understand something hinkey could happen here. Usually, it’s going to be a more senior person or some other person like that. If it’s another writer, be especially alarmed because that can be weird. That’s happened a couple of times where it’s like, “Why are you there, Mr. High-profile screenwriter? That doesn’t feel great to me.”

Liz: Who I know comes on and does rewrites. That’s so weird that you’re here.

John: That’s so weird. Maybe you’re thinking about the same person who’s been in that room. If that happens, that’s reasonable. Sometimes it is actually that junior executive. I’ve been in a couple of situations, “Why is this person doing this? Why is this person here?” First off, it’s great if they’re there to learn stuff, but when they then ask the questions and pull stuff, in TV pitches, I’ve had this happen more often, where they start to ask you for needless detail. I’m like, “Oh, okay, great, I’ll help you out here.”

Liz: I agree, but I don’t think any stranger in the room is there without a goal. Unless you have invited them there, unless you as the writer have invited a friend or something like that to hear this. If there’s an intern in the room, the intern is trying to prove to their bosses why they should have a promotion. If the writer is there, they’re proving to their bosses that they’re going to get the rewrite. You have to really evaluate the stranger in the room’s intention. Most often, there is something behind it. That doesn’t mean it’s malicious to you. It doesn’t mean that it’s personal. It also doesn’t mean that they’re wrong. It just means, again, going back to how it’s being delivered and the surprise factor.

To be frank, when you get to that stage and you have a junior executive that’s never been in a meeting start giving notes, you’re kind of like, “Wait, haven’t we gotten past this?” It can be alarming. I always try and think about notes in any stage, be it a stranger in the room or an evil person in the room, just to think about the context in which the note is coming to you.

John: Absolutely. If you are that intern in the room, the person who’s invited in, try to get a sense, you can even ask ahead of time, “What do you want me to do in this room?” Especially if you’re talking to the writer or the creatives, you have to be respectful and delicate and make sure you’re leading with some praise and if you’re asking a question, there’s nothing in that question that has a subtext of like, “You idiot, this doesn’t make any sense.” That’s where you run into problems.

Let’s answer some listener questions. Let’s start with, “It’s not you, it’s me.”

Drew: “After a little industry success, I’m now discovering that I have friends, distant relatives, and son acquaintances who want to pick my brain or set me up on blind date-style meetings with my cousin who just started film school. I’ve even had friends and relatives share my email address without asking me. I like to share with people who are starting out, as a few people did for me when I started. However, I’m not sure how to decline when the connection is forced and I don’t want the obligation or how to distance when someone becomes too persistent, asking for Zoom after Zoom, sending life story emails, or asking to send me their screenplays. How do you guys deal with getting cornered by family and friends? How do you deal with clingers?”

John: Okay, so my mom, rest in peace, love her to death, but she would try to connect me with anybody and everybody. She was overgenerous about this. I had to step in and say, “Mom, you need to stop doing that. This is not useful for anybody. I will talk to your Boulder Screenwriters Group once, but I’m not going to do it every year. I’m not going to do it all the time.” I think Craig and I have the convenient excuse of we do a podcast every week that everyone can listen to and that’s the conversation. Before I did that, and for everybody else who doesn’t have their own podcast, bless you. Liz, do you have any suggestions for ways to be tactful and helpful but not deal with clingers?

Liz: Yes. Boundary is really important. Establishing that you cannot share your personal information that cannot be shared is really important. I also have a work email and a personal email. I think having those two, still setting boundaries, but those two are really important because if there is someone that you feel that you can be helpful to or feels polite and appropriate that you can reach out to, then you can do that from your work email. I know that it seems silly, but it does not feel as disruptive to me when it’s going to my work email. It feels like that’s the right avenue for it to happen.

Look, I try and talk to whoever I can. I try and be as helpful with my time and energy as I can be because I had a lot of people be helpful with theirs when I was coming up, you being one of them. I don’t have a podcast, so trying to do that is important. Having the ability to say, “Look, I totally would love to talk to you. My life is really crazy right now, so I can do it for an hour in March or I can do a 15-minute call now or I can do–” I just think really boundaries and being honest with yourself that you are a kind person for having any conversation and extolling any experience to people is really going above and beyond.

John: Yes, I completely agree with you on boundaries. Also, just establishing those boundaries at the start in a really friendly way. Saying, “I don’t have the time to read anything.” The truth is we’re all crazy all the time. We never really have time to do things. You can also say, “I’m sorry, but no, I can’t.” That’s also fair too. People have busy lives.

Listen, I have Drew and so Drew is the first filtering mechanism for people who are going to try come at me. Even independent of that, I think you just have to have your own system for saying no and not feeling awful about it or ignoring things and not feeling awful about it. That’s the reality. People ignore emails all the time. It’s not a crime.

Liz: I would say also go with your gut. I honestly have – knock on wood – had 99% wonderful experiences with people that have reached out or asked for a Zoom, a coffee, or whatever. I don’t read scripts unless it’s from somebody I know.

John: Same.

Liz: I think that is a step too far for me. I always just go legally, it’s a step too far. If you’re looking for a way to say, “No, I can’t read that, but I’ll talk to you,” then that’s the way I always go. It’s like, “I can’t read your script legally; it’s too complex for me to do that, but I’m happy to talk to you about what issues you’re having storytelling-wise and see if I can help.”

John: The other thing I think is useful for me to say, which is absolutely 100% true, is that when it comes to how do I break into the industry? How do I do this? How do I do this stuff? I can talk to you about scene work. I can talk to you about how movies work. I cannot talk to you about what it’s like to be a 20-something-year-old starting in 2025 in this town. That’s just not my experience. You’re much better off dealing with people who are just there and have just moved through that space than I will be.

One of the reasons why we try to keep bringing on guests who are newer in the industry is to make sure that we’re still hitting the realities of what it’s like to be in those moments right now because like, Craig and our experience, it’s 30 years past that, and it’s not the experience of starting in 2025. Let’s go to Dean, who’s writing about the visual effects industry.

Drew: “Regarding the sudden shutdown of The Mill and MPC and Hollywood VFX in general, how is it that these giant companies working on some of the biggest and most profitable movies and shows in the world keep going bankrupt? Their work is world-class. It keeps happening. What is it about VFX that is clearly unsustainable?”

John: Clearly, this email came in before Technicolor also shut down. It’s horrible. Listen, I don’t understand VFX economics, but clearly, a different situation has to be figured out because we’re able to do incredible visual effects and we’re spending a ton of money on visual effects, and it’s still not enough for these companies to be profitable and sustainable. Something big has to shift here. Liz, do you have any insight? Do you know anything about this space?

Liz: No, I don’t. Everything has VFX, so it’s horrific what’s happening. Again, I don’t know the economics of it, but it doesn’t make sense to me. There has to be a change.

John: Great. All right, let’s do our One Cool Things. Thank you to everybody who’s been playing Birdigo. We’re still up on Steam. The demo is still there, which is great. A game I’ve been playing a lot over this last month, and I think I’ve broken my addiction, so maybe I need to pass it along. It’s like the ring where I need to get other people to play this game, which was fun. It’s called Dragonsweeper, and it’s like Minesweeper that we all played, where you’re looking for the little mines, except there are various monsters hidden around. It’s by Daniel Benmergui. It is a free game that you play in your browser. It takes maybe half an hour to do once you’ve mastered it.

It’s a really clever mechanic and gets your brain to think in really interesting ways. If you need a distraction, if you just need your brain to stop ruminating on things it’s ruminating on, I point people towards Dragonsweeper, which is a benevolent time suck that I’ve found over the last couple of weeks.

Liz: Love that.

John: Liz, what do you have for us?

Liz: I have a one and a half one cool thing.

John: I love it, please.

Liz: Both my mother and my best friend were diagnosed with breast cancer last year. Both are okay and recovering and in remission.

John: Great.

Liz: My big thing is mammograms. One cool thing, love a mammogram. Mammograms are not covered by insurance until you’re 40 years old, and my best friend was 38 when she was diagnosed. More and more women are being diagnosed with breast cancer in their 30s or younger. If you have really any cancer in your family, you should be going to get tested. If it’s not covered by insurance, you can find ways to do it. There are really great ways to do it. My boobs, my two cool things.

Then the plus to that also is that in this experience, I’ve learned a lot about how women’s health is just shockingly underfunded and under-researched. One of the aspects of that is menopause and perimenopause, which has been something that’s been talked about a lot. Many of my family members have had to, either because of cancer or because of age, anything like that, gone through it earlier.

Naomi Watts just wrote a book, which is called Dare I Say It, which is about menopause and how she went into menopause in her 30s. It was shocking. Then, she discovered that many other women went through it as well and that menopause is not that thing that just happens when you’re 50 years old, that it’s actually something that progresses through your life. My addition to this is also to read Naomi Watts’ book, which I think is really enlightening and makes something that feels very, very scary and isolating, not that. Also, women should be talking about their health just as much as men do. That’s it.

John: These are great things. In terms of cancer screening, like we’ve heard, I’ve talked about colonoscopies on the show several times. I think it’s underappreciated to the degree to which there are certain cancers, certain terrible things that just with not horrible tests, you can just actually deal with it. Things that are grave threats that are not threats if you actually just get the test and get it early enough to see what’s there. Mammograms are 100% in that category.

Liz: My best friend actually, and she’s talked about this publicly, so I feel comfortable saying it, she had a rash on her chest. She was under the age of 40. The only reason that they found the cancer was because of this rash. Her doctor said that she should just go get a mammogram and get checked. If they had waited until it was stage 1, if they had waited until she was 40, God knows what that would have been and what would have happened. It is crazy that it’s on us to be like, “Hmm, that rash on our chest, maybe that’s cancer.” But there are preventative ways to find these early that are not necessarily constantly talked about or open.

John: Yes, great. That is our show for this week. Scriptnotes is produced by Drew Marquardt, edited by Matthew Chilelli. Outro this week is by Spencer Lackey. If you have an outro, you can send us a link to ask@johnaugust.com. That’s also the place where you can send questions like the ones we answered today.

You’ll find transcripts at johnaugust.com, along with the sign-up for our weekly newsletter called Interesting, which has lots of links to things about writing. We have t-shirts, hoodies, and drinkware. You’ll find all those at Cotton Bureau. You can find show notes with the links to all the things we talked about today in the email you get each week as a premium subscriber. Thank you to all our premium subscribers. You make it possible for us to do this each and every week.

You get signed up to become a premium subscriber at scriptnotes.net, where you get all those back episodes and bonus segments like the one we’re about to record on East Side vs West Side. Liz Hannah, no matter what side, I want to be on your side because you were a fantastic return guest. Thank you so much for being on the show this week.

Liz: Thanks for having me. It was great.

[Bonus Segment]

John: All right, Liz Hannah, you and I, we’re east siders by definition that we’re not on the west side. We’re actually in the middle of the city. If you’re able to look at the platonic ideal of Los Angeles, we’re plopped in the middle of it. For folks who are outside of Los Angeles, which is a big chunk of our listenership, I feel like I want to give a little geography lesson and a little geography explanation because your choice of whether you live on the west side or the east side is going to fundamentally shape some of your experience of living in Los Angeles. Can you talk to us about when you were first aware of there’s a big difference between living East and West?

Liz: Yes. My mom is from LA so I grew up coming here a lot, but I still didn’t understand it until I went to AFI. AFI is on the east side. It’s in Los Feliz. I lived in West LA, which is on the west side. That commute was really hell. It was awful. Significantly changed my experience for my first year of AFI. Then my second year, I lived in Los Feliz on the east side.

It was both my first time living here as an adult. I understand, also, coming from New York, just how much in your car you are in, in general, and then how much more you are in your car if you live on one of these sides and you must commute to the other.

John: Yes. There’s not a perfect New York comparison, but it’s like if you lived in Brooklyn, but you’re traveling to the furthest north place in Manhattan, if you’re traveling to cross 110th Street every day all the time, but it’s actually not quite a fair comparison because there’s just trains that can get you there directly.

Liz: You can do things on the train. You can read books.

John: You can do things on the train rather than being trapped in your car. The reason why the East-West split is so noticeable in Los Angeles versus the North-South split is because while there are some freeways that go East to West, you have to cross the 405. The 405 is sort of the boundary, the dividing line between what we think about East and West. If you have to cross the 405 at certain times of day or cross that imaginary wall, it’s just awful.

I would have meetings that would be out at Bruckheimer’s company, which is on the west side, and lord, an hour and 15 minutes later I’m finally home based on the time of the day. You have to plan things so carefully. That’s why I think Taffy Brodesser-Akner, when she was out here doing her book tour, she had an east side event and a west side event because they’re fundamentally different things.

Liz: They’re two different worlds. I think also they’re culturally very different. It sounds stereotypical, but West Siders are just a little more relaxed. They like nature a lot and they love the beach. That’s just what it is. Well, nature, not so much, but the beach. That nature, I think is shared.

John: They love the beach.

Liz: Nature is shared by all because there’s hikes everywhere in Los Angeles.

John: Yes. They live in a city that has a beach and you and I live in a city that does not have a beach.

Liz: No, we live in the city and they live in a beach city. Those are the fundamental differences. I think there’s like a walkability aspect to both the west side than the east side that exists, but it’s very different in those walkabilities and where they are. It’s just culturally very different.

John: Yes. There are things that are similar between the two. They have Abbot-Kinney, we have Larchmont, we have certain central points, but things do just fundamentally work differently.

Liz: A friend of mine lives on the east side and started dating somebody on the west side and we call it a long-distance relationship.

John: It is.

Liz: That is a commitment that you are making.

John: I moved out here for grad school and I was going to grad school at USC, which is east side and sort of South of the 10-2. Things are a little bit thrown off for that. I had some friends who lived on the west side and some friends who lived in Los Feliz, Hollywood. The differences between those things are vast. One of my friends, Tom, I would work out at the YMCA with him on the west side, but I was living in Hollywood. Good lord, that commute to get back from the gym was insane. On one of those commutes back, I happened to drive over the 405 and it was during OJ’s Bronco chase. I was able to stop on the bridge over the 405 and see OJ Simpson drive along this boundary wall between East Los Angeles and West Los Angeles.

Liz: That was the last time you drove to the west side?

John: Honestly, I think I did stop going to the gym shortly thereafter. I just realized it’s a fundamentally different thing.

Liz: I also live in the Valley now, which not to complicate it more, but like that’s–

John: We should talk about that.

Liz: The Valley is like above it all. I would refer to it more as east side than it is west side, just because it still has the dividing line of the 405. Once you get far west in the Valley, you’re basically in Topanga and Malibu. It’s more east side. I will just say that I can get to Silver Lake faster from where I live than whenever I lived in West Hollywood. Freeways are great. I just feel like now we’re in an episode of The Californians.

John: We are very much in an episode of The Californians. It does come down to that. Some practical takeaways here. If you are coming to visit Los Angeles, like, “I want to see Los Angeles–” I will have people who will show up and say like, “Oh, well, today I want to see the Hollywood Walk of Fame and I want to go to the beach and I want to go to Getty center and all these things.” It’s like, you’re insane.

Liz: Also have a great time doing that without me. No, I’m good. Thank you.

John: “No, I’m not going to do that with you.” You are going to be in your car the entire time. If you are literally out here for a week and you want to see all those things, three days in Hollywood, three days on the beach, split up your time because you’re not going to make yourself happy trying to do all those things from one central point.

The bigger question, though, is if you are moving to Los Angeles or you’ve taken a job or coming here to school, you have to make some fundamental choices. I would say, you’re probably best off living close to where you’re going to be spending most of your time just so you’re not killing yourself driving places. While there are more train options and bus options than ever before, still, you get a little bit trapped by the geography.

Liz: I would also suggest, do a Vrbo or something and stay in different places before you commit to where you want to live. One of my best friends lives on the west side and I joked when she moved there. She moved there from New York and I was like, “Well, I’ll never see you again.” She will drive to me. I was like, “Great.” She doesn’t mind doing that. It was important for her and her kids to live on the west side and she knew the burden she was taking on by moving across that, near the end of the world. Now she’s back. I think you have to sort of find your neighborhood and find your place. It is like New York.

John: Yes, very much.

Liz: While we’re saying east and west, there are pockets of neighborhoods within each of them that have their own personalities and their own quirks and things like that. I lived on the east side for a really long time but I never lived in Echo Park or Silver Lake but I lived in Los Feliz. I lived in Hancock Park. I lived in West Hollywood. Now I live in the valley, just FYI, the streets are so wide here. There’s no street, parking [crosstalk]. It’s lovely.

John: Yes. There’s no reason the streets need to be as wide. It’s lovely.

Liz: It’s glorious. Now I’m like the old person who drives in West Hollywood, and I’m like, “These streets are too small.” I think you just find your place, you find your people. Don’t rush it and say–

John: Agreed.

Liz: I do think what you said is really important is, if you are coming out here, for instance, to go to grad school and you’re going to go to USC or you’re going to go to AFI, find a hub that is localized around that.

John: Yes. Because otherwise, you’re going to be angry at yourself for two years that you made the choice that you made.

Liz: Yes.

John: All right. It’s always a great choice to talk with you. Liz Hannah, thank you for Zooming in all the way from the valley.

Liz: Thank you.

John: Let’s talk more soon.

Liz: Love it. Bye. Bye.

Links:

- Liz Hannah on IMDb and Instagram

- Episode 676 – Writing while the World is on Fire

- Slate Culture Gabfest

- The Post | Screenplay

- Episode 128 – Frozen with Jennifer Lee

- Into the Unknown: Making Frozen 2 on Disney+

- Highland Pro

- The Girl From Plainville on Hulu

- The Dropout on Hulu

- “The Stranger in the Room” by @toddalcott on Threads

- Episode 399 – Notes on Notes

- Dragonsweeper by Daniel Benmergui

- Dare I Say It by Naomi Watts

- Get a Scriptnotes T-shirt!

- Check out the Inneresting Newsletter

- Gift a Scriptnotes Subscription or treat yourself to a premium subscription!

- Craig Mazin on Threads and Instagram

- John August on Bluesky, Threads, and Instagram

- Outro by Spencer Lackey (send us yours!)

- Scriptnotes is produced by Drew Marquardt and edited by Matthew Chilelli.

Email us at ask@johnaugust.com

You can download the episode here.The post Scriptnotes, Episode 679: The Driver’s Seat, Transcript first appeared on John August.

![New Update Celebrating the 10th Anniversary of ‘Mortal Kombat Mobile’ Available Now [Trailer]](https://bloody-disgusting.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/mkmobile.jpg)

.png?format=1500w#)

![‘They Told Me To Unplug His Life Support’: Mom Says United Airlines Targeted Her Toddler [Roundup]](https://viewfromthewing.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/united-airlines-empty-economy-plus.jpg?#)

![She Missed Her Alaska Airlines Crush—Then A Commenter Shared A Genius Trick To Find Him [Roundup]](https://viewfromthewing.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/alaska-airlines-in-san-diego.jpg?#)

.jpg?width=1920&height=1920&fit=bounds&quality=80&format=jpg&auto=webp#)

![[Podcast] Should Brands Get Political? The Risks & Rewards of Taking a Stand with Jeroen Reuven Bours](https://justcreative.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/jeroen-reuven-youtube-1.png)