How Ken Burns’ “Shadow Ball” Connects Baseball’s Past to Our Uncertain Future

To watch the fifth episode of Ken Burns' "Baseball" is to see exactly what makes the sport great as a metaphor for the country.

Rarely does it matter that Ken Burns’ “Baseball,” an immersive ten-part docuseries about the history of America’s pastime, is built on frustrating inaccuracies, fetishizes an East Coast narrative, or runs out of steam once you get to the modern game. All of those weaknesses fade in comparison to the series’ importance as an oral historical document, particularly in Episode 5: “Shadow Ball.” That episode, next to the sixth, which covers Jackie Robinson’s distinctly political act of breaking the color barrier, is about those who paved the way for him in the Negro Leagues. For “Shadow Ball,” Burns gathered some of the last surviving players from the era to reminisce about a brand of baseball that really only exists in their collective memory.

Burns’ preservationist efforts, which give life to tall tales, faded triumphs, and unhealed wounds and cover baseball’s traveling to Japan and Latin America, are especially relevant now considering the erasure of this history and the anti-immigration stance taken by the Trump administration. To watch “Shadow Ball” is to see exactly what makes the sport great as a metaphor for the country.

As a piece of media, “Baseball” was relatively ahead of its time. Before “Baseball,” Alfred E. Green’s biopic “The Jackie Robinson Story,” wherein Robinson starred as himself, John Badham’s waggish blaxploitation classic “The Bingo Long Traveling All-Stars and Motor Kings,” and the Louis Gossett Jr led TV movie “Don’t Look Back: The Story of Leroy ‘Satchel’ Paige,” represented the few cinematic acknowledgments of the Negro Leagues. There were, up until 1994, when the docuseries was released, even fewer documentaries, even less newsreel material, and barely any surviving box scores (the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum, which opened in 1990, was also simultaneously collating these resources too).

Luckily for Burns, he did have a few resources. Several archives, libraries and heritage societies, the Negro League Baseball Players Association, articles from the Chicago Defender (which are narrated here by Ossie Davis), and player-manager Buck O’Neil. Through these references, Burns was able to bring together archival photographs, newsreels and former players like Sammy Haynes, Riley Stewart, Slick Surratt, Connie Johnson, Double Duty Radcliffe and O’Neil to tell the story of the league.

Part five, which spans 1930 through 1940, begins on a telling note. “The idea of community, the idea of coming together, we’re still not good at that in this country,” explains former New York governor Mario Cuomo. While “Shadow Ball” weaves through New York baseball history: Ruth’s waning glory, the rise of Lou Gehrig, and the origin of the Dodgers’ “bums” nickname—it most often attempts to define the importance of community.

Here, community isn’t so much defined as a neighborhood or a collection of addresses, but as a wider fabric. In the eyes of Cuomo, America and its pastime are defined by the ability to integrate different races, nationalities, religions, and cultures into the broader definition of the country. For Burns, that belief, and America’s persistent inability to match it, is best expressed through the history of the Negro Leagues.

For much of “Baseball,” Burns leans on oral history to recall the early events of the sport. Oftentimes, the apocryphal nature of these yarns further establishes baseball as a mythological text filled with larger-than-life characters. In relation to the Negro Leagues, the apocryphal approach is a bitter pill because, with scant record keeping, the words of those who lived the game are the only ones who can prove that its greatest feats ever happened. Through the words of retired players, we learn about the league’s colorful characters. And through the archival footage and photographs of them in action, we see the energy, fluidity, confidence and daring they brought to the game.

In “Shadow Ball,” the Golden Age teams followed by Burns are the Homestead Grays, Pittsburgh Crawfords, and Kansas City Monarchs. By this point in the Negro Leagues, the version covered in this episode was the second iteration of the organized baseball association, which followed the collapse of owner-pitcher Rube Foster’s first design, which was at its high-water mark. Some teams were owned by flamboyant racketeers and pop culture sensations such as Louis Armstrong, Cab Calloway, and Bill “Bojangles” Robinson and led by big stars like “Cool Papa” Bell, who many claimed was so fast, you could cut off the light and he’d be in bed before it was dark; Josh Gibson, who might’ve hit over 800 home runs; and Satchel Paige, an incredible pitcher known for side-splitting aphorisms and uncommon confidence.

To be sure, the league was entertaining, but it was also politically and culturally important. Newark Eagles owner Effa Manley often donated the gate of her team’s games to support the NAACP and the period’s anti-lynching legislation. In an era of virulent racism, the league became a point of pride for Black Americans, too, who, through athletics, seized their chance to prove their ability through exhibition games. Per “Baseball,” Black stars played their White counterparts “at least 438 times in off-season exhibition games.” The Whites won 129 games. The Black players won 309. “That’s when we played the hardest,” the series quotes a Black veteran as saying. “To let them know and to let the public know that we had the same talent they did, and probably a little better at times.”

While Burns and the series’ many talking heads stop short of saying Negro League players were consciously political figures, it’s clear they knew their importance to the Black community. O’Neil, for instance, shares how they figuratively “carried the news” across the country by telling people in small towns about the events they witnessed in other places. O’Neil also recounts a story of visiting Drum Island, South Carolina with Paige, where enslaved Africans were auctioned off, and feeling a spiritual tie to the infamous location.

Conversely, Burns spotlights the painful limitations felt by Black ballplayers who wanted to see change. “We knew what the situation was, so you couldn’t change those people’s ideas down in that part of the country. So why go down there and try to fight it,” explains Surratt, who played for the Detroit Stars and Monarchs. “If he said come to the back for a sandwich, well, we were hungry, we would go to the back for a sandwich. We wasn’t trying to go down there and change the rules because when the government can’t break the rules, now, what can a ballplayer do?” Burns’ camera, tellingly, holds on Surratt. The retired ballplayer bites his lips, and in his eyes, you can perceive how the agony of those memories still affects him.

For “Baseball,” the exploits and tragedies of the Negro Leagues don’t exist in a political vacuum. Toward the middle of the episode, Burns not only makes sure to note that “by 1934 the world economy was in ruins and fascism was on the rise.” He also uses the geopolitical upheaval of the era to highlight the spreading of the sport across cultures and borders.

Foreshadowing the current wave of Asian superstars, the recounting of Babe Ruth’s tour of Japan highlights 17-year-old Japanese pitcher Eiji Sawamura’s feat of striking out Ruth, Jimmie Fox, Lou Gehrig, and Charlie Gehringer in a game. Dominican Republic dictator Rafael Trujillo’s 1937 recruitment of Negro players takes viewers into the prejudice faced by dark-skinned Latin American ballplayers. Jewish first baseman Hank Greenberg’s chase of Ruth’s single-season home run record in 1938 is contextualized through the era’s antisemitism. Burns is, once again, careful not to call these consciously political acts. Rather, he highlights them because he knows that to move into and exist within a space dominated by White Anglo powerbrokers is inherently political.

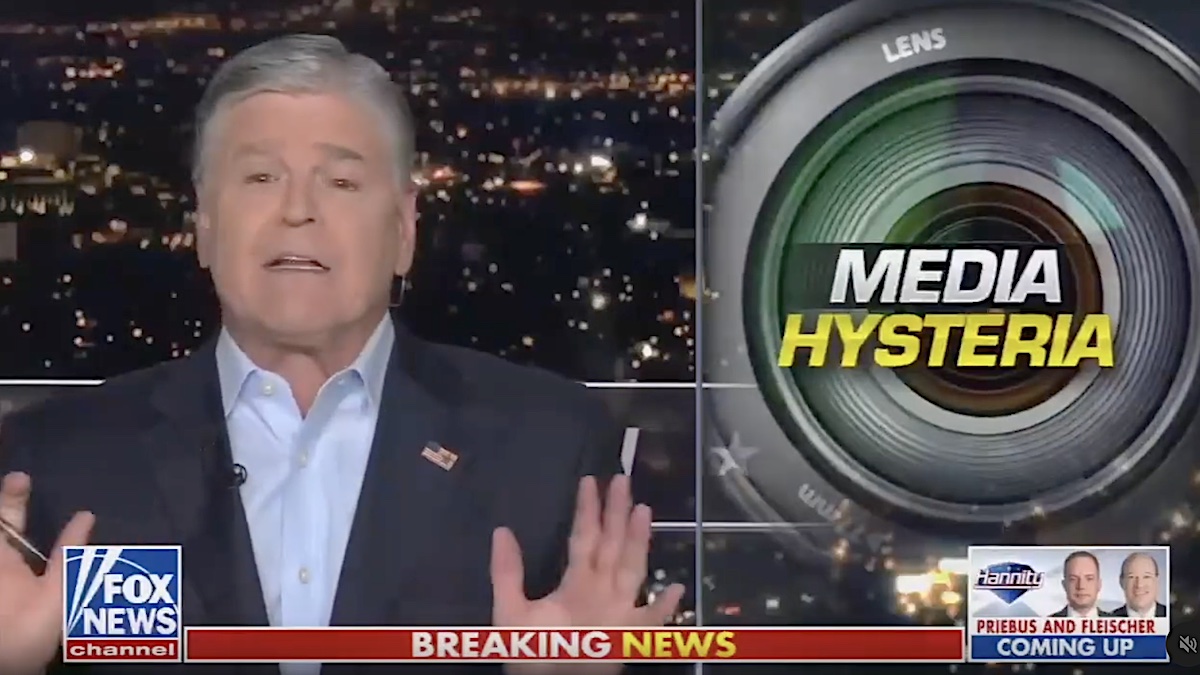

We can feel the importance of these athletes’ destabilizing strides today in the rise of fascism in America. Just last week, the Pentagon removed any mention of Jackie Robinson from its website only to add it back after an uproar online. When ESPN questioned Pentagon press secretary John Ullyot why Robinson was scrubbed from the website, he offered a chilling respond: “DEI is dead at the Defense Department. Discriminatory Equity Ideology is a form of Woke cultural Marxism that has no place in our military.” Later, Ullyot would claim that Robinson was removed in error.

Such erasure of Black baseball’s cultural significance can be located in the “anti-woke” discourse that can either be heard quietly or very loudly on social media. On X, formerly known as Twitter, retired NFL quarterback Robert Griffin III made the outlandish claim that “Breaking the color barrier in baseball in itself is not political” in reply to a tweet that initially stated, “Sports shows on TV should be about sports not politics,” a critique that was interpreted as a clear jab against Mina Kimes’ “Around the Horn” defense of Robinson’s legacy.

The desire to separate sports from politics, especially from achievements rooted in equality, isn’t unlike the Trump administration’s anti-immigrant impulses to define America’s past, present, and future as a cis White monoculture. It is a want to erase the notion of community and difference, to extinguish the spirit to defend your neighbor or to uplift those most vulnerable no matter what you may lose in the process.

“I love bunt plays, the idea of the bunt. I love the idea of the sacrifice, even the word is good. Giving yourself up for the good of the whole,” explains Cuomo in “Baseball.” “That’s Jeremiah. That’s thousands of years of wisdom. You find your own good in the good of the whole. You find your own individual success in the success of the community. The Bible tried to do that and didn’t teach you. Baseball did.”

That lesson still hasn’t taken. Not only has our sense of community eroded, if it ever existed, so has the cultural prominence of baseball. The sport isn’t really America’s pastime anymore, and therefore, struggles to fortify the mythology of America as a place of inherent fairness where you’re offered three strikes along with the chance to prove your worth. It’s all a shame, a curve we continue to swing through.

Still, through “Shadow Ball,” Burns attempts to teach viewers. In the story of the Negro Leagues, leading to the eventual integration of baseball, which is covered in part six, Burns demonstrates why it’s imperative that we record our shared history and talk about our flawed record on equality. By seeing baseball as an example of how much better the game can be when it’s shared by all, we might see how racism, xenophobia, jingoism, and fascism can only lead to danger. You need allies, you need community, you need difference or else you’ll merely be chasing a shadow.

“Baseball” can be watched VOD on Apple, Fandango at Home, Amazon, and other streaming platforms.

![Tommy Boy Director's Favorite Chris Farley Memory Involves A Classic Movie Star Impression And Some Car Chaos [Exclusive]](https://www.slashfilm.com/img/gallery/one-of-tommy-boys-most-quotable-moments-came-from-chris-farley-being-bored-exclusive/l-intro-1742930645.jpg?#)

![She Missed Her Alaska Airlines Crush—Then A Commenter Shared A Genius Trick To Find Him [Roundup]](https://viewfromthewing.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/alaska-airlines-in-san-diego.jpg?#)

.png?width=1920&height=1920&fit=bounds&quality=80&format=jpg&auto=webp#)

.png?width=1920&height=1920&fit=bounds&quality=80&format=jpg&auto=webp#)

![[Podcast] Should Brands Get Political? The Risks & Rewards of Taking a Stand with Jeroen Reuven Bours](https://justcreative.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/jeroen-reuven-youtube-1.png)