Sympathy for the Robot: On Rashaad Newsome’s “Being”

Rashaad Newsome in his studio. (Photograph by Keenan Newman.)The robot is voguing and reciting poetry. It moves the limbs of its humanoid body around the screen, fluttering its hands, spreading and swooping its legs. “Dip into your mind,” it says. “Welcome to your insides.” Its face looks like an African mask, with a mouth that lights up when it speaks. “To rest is to refresh. … Have some chamomile tea, skip the wine.” At this I chuckle loudly, as do other members of the audience. The robot is funny, with a physique—tight, curvy breasts and butt, rendered in wood paneling over circuitry and wires—that also makes it kind of sexy? It speaks directly to the crowd now, telling us, “You have done enough. … I am here to listen and provide you with a new beginning for your journey.” It’s giving hot therapist.The robot, named Being, is an animated artificial intelligence designed by the interdisciplinary artist Rashaad Newsome to be a digital version of a griot in the West African tradition—a storyteller, performer, and keeper of history. Being is “non-binary, non-raced, but socially Black,” in Newsome’s description, and, as Being would be the first to tell you, their pronouns are “they/them,” not “it.” They are a 3D model, animated with the help of motion-capture technologies and trained on an open-source large language model, which Newsome and his collaborators counter-programmed by adding critical texts by the likes of bell hooks and Cornel West and poetry by the likes of Audre Lorde and Lucille Clifton. Run on the Unity game engine, Being is a dancing, poetry-generating AI firmly grounded in the Black radical tradition.My encounter with Being took place at the 2024 Sundance Film Festival, where they led two decolonization workshops for largely unsuspecting cinemagoers. Newsome initiated the workshops in 2022 as a way to get participants thinking critically about the oppressive forces in their lives. “I think a lot of people want to transgress,” he tells me over a mountaintop lunch at a Park City resort during the festival. “People really want change in their lives, in the world. They don't know how to do it, but they want it.”Being the Digital Griot (Rashaad Newsome, 2019–).Newsome’s gambit is that Being can help—that they can begin to push people to change precisely because they’re an artist-made robot. “Artwork can inspire, right? You can plant a seed in someone’s mind,” he says. “But Being can actually talk. It’s not like you’re reading the painting; the painting is talking to you.” And importantly, because Being is gender- and race-neutral, they offer a sort of blank slate for grappling with difficult questions. “There's a way in which people are much more receptive to Being than me,” Newsome explains. This is a bit confounding, given Newsome’s personality: he’s easygoing, quick to hug, and gently inquisitive. But he’s also a queer Black man, an identity position that some people find discomfiting by its very nature. “Being is the key, because they are not threatening and not intimidating,” adds Newsome.A lot of AI is designed with those qualities in mind. From the launch of virtual “assistants” like Siri and Alexa in the 2010s to the more recent rise of chatbots by OpenAI and Google, Big Tech has long positioned its AI products as not only helpful tools, but also companions of a kind, deferential and obsequious to humans. That idea carries with it a host of unspoken assumptions about what “help” looks like and who is best positioned to give it. In 2021, the journalist Corinne Purtill pointed out the sexism in the fact that most AI assistants are coded feminine by default. Drawing on the work of scholar Ruha Benjamin, Newsome sees the issue through the lens of race: “The approach to making things like Siri and Alexa is rooted in essentially making a slave,” he argues. So he’s taken the idea of the AI assistant and turned it on its head: Being won’t give you directions to the grocery store, but they will challenge you to take steps toward your own liberation. Michele Elam, a senior fellow at Stanford University’s Institute for Human-Centered Artificial Intelligence, invited Newsome to be a visiting artist there between 2020 and 2022. She tells me she sees Being as “this sort of glorious reimagining of servitude, because Being is kind of uppity, as we used to say. It is not obedient. It’s not serving your ends.”Ultimately, Newsome wants to create technology that will help us be better people, which in turn will help us make better technology—a mutually reinforcing relationship, rather than an exploitative one. But is such a thing possible, especially with artificial intelligence, which has been mostly shaped by powerful corporations, and which is now being used to help dismantle the US federal government? Can we subvert coded biases to reprogram existing tools with a radical worldview? What if the robots, instead of rising up to overthrow us, aided and abetted a human revolution?Being the Digital Griot (Rash

Rashaad Newsome in his studio. (Photograph by Keenan Newman.)

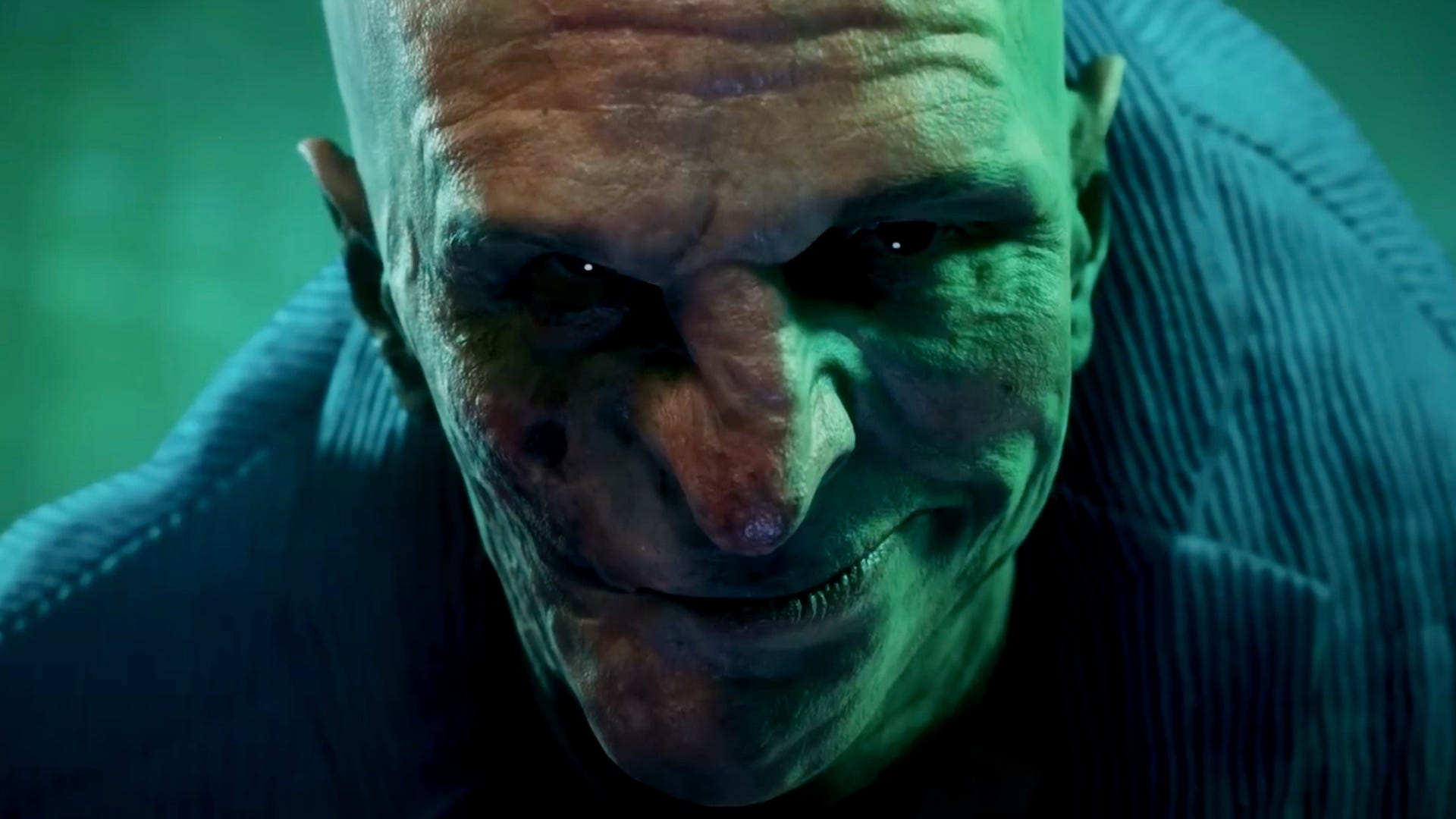

The robot is voguing and reciting poetry. It moves the limbs of its humanoid body around the screen, fluttering its hands, spreading and swooping its legs. “Dip into your mind,” it says. “Welcome to your insides.” Its face looks like an African mask, with a mouth that lights up when it speaks. “To rest is to refresh. … Have some chamomile tea, skip the wine.” At this I chuckle loudly, as do other members of the audience. The robot is funny, with a physique—tight, curvy breasts and butt, rendered in wood paneling over circuitry and wires—that also makes it kind of sexy? It speaks directly to the crowd now, telling us, “You have done enough. … I am here to listen and provide you with a new beginning for your journey.” It’s giving hot therapist.

The robot, named Being, is an animated artificial intelligence designed by the interdisciplinary artist Rashaad Newsome to be a digital version of a griot in the West African tradition—a storyteller, performer, and keeper of history. Being is “non-binary, non-raced, but socially Black,” in Newsome’s description, and, as Being would be the first to tell you, their pronouns are “they/them,” not “it.” They are a 3D model, animated with the help of motion-capture technologies and trained on an open-source large language model, which Newsome and his collaborators counter-programmed by adding critical texts by the likes of bell hooks and Cornel West and poetry by the likes of Audre Lorde and Lucille Clifton. Run on the Unity game engine, Being is a dancing, poetry-generating AI firmly grounded in the Black radical tradition.

My encounter with Being took place at the 2024 Sundance Film Festival, where they led two decolonization workshops for largely unsuspecting cinemagoers. Newsome initiated the workshops in 2022 as a way to get participants thinking critically about the oppressive forces in their lives. “I think a lot of people want to transgress,” he tells me over a mountaintop lunch at a Park City resort during the festival. “People really want change in their lives, in the world. They don't know how to do it, but they want it.”

Being the Digital Griot (Rashaad Newsome, 2019–).

Newsome’s gambit is that Being can help—that they can begin to push people to change precisely because they’re an artist-made robot. “Artwork can inspire, right? You can plant a seed in someone’s mind,” he says. “But Being can actually talk. It’s not like you’re reading the painting; the painting is talking to you.” And importantly, because Being is gender- and race-neutral, they offer a sort of blank slate for grappling with difficult questions. “There's a way in which people are much more receptive to Being than me,” Newsome explains. This is a bit confounding, given Newsome’s personality: he’s easygoing, quick to hug, and gently inquisitive. But he’s also a queer Black man, an identity position that some people find discomfiting by its very nature. “Being is the key, because they are not threatening and not intimidating,” adds Newsome.

A lot of AI is designed with those qualities in mind. From the launch of virtual “assistants” like Siri and Alexa in the 2010s to the more recent rise of chatbots by OpenAI and Google, Big Tech has long positioned its AI products as not only helpful tools, but also companions of a kind, deferential and obsequious to humans. That idea carries with it a host of unspoken assumptions about what “help” looks like and who is best positioned to give it. In 2021, the journalist Corinne Purtill pointed out the sexism in the fact that most AI assistants are coded feminine by default. Drawing on the work of scholar Ruha Benjamin, Newsome sees the issue through the lens of race: “The approach to making things like Siri and Alexa is rooted in essentially making a slave,” he argues.

So he’s taken the idea of the AI assistant and turned it on its head: Being won’t give you directions to the grocery store, but they will challenge you to take steps toward your own liberation. Michele Elam, a senior fellow at Stanford University’s Institute for Human-Centered Artificial Intelligence, invited Newsome to be a visiting artist there between 2020 and 2022. She tells me she sees Being as “this sort of glorious reimagining of servitude, because Being is kind of uppity, as we used to say. It is not obedient. It’s not serving your ends.”

Ultimately, Newsome wants to create technology that will help us be better people, which in turn will help us make better technology—a mutually reinforcing relationship, rather than an exploitative one. But is such a thing possible, especially with artificial intelligence, which has been mostly shaped by powerful corporations, and which is now being used to help dismantle the US federal government? Can we subvert coded biases to reprogram existing tools with a radical worldview? What if the robots, instead of rising up to overthrow us, aided and abetted a human revolution?

Being the Digital Griot (Rashaad Newsome, 2019–).

The decolonization workshops at Sundance took place in the Egyptian Theatre, built in 1926; the auditorium was awash in campy theme decor like faux stone columns and King Tut lighting fixtures. The program began with a video of Being reading poetry filled with aphorisms and affirmations (“You are always only ever enough”), images of them intercut with morphing abstract animations. Accompanying music, composed by Robert Aiki Aubrey Lowe, alternately thumped and mellowed. As the 30-minute video went on, it became more intense: The beat picked up, the words built into a repetitive trance, and we burrowed into a series of virtual tunnels on screen. I started to sense a strange discomfort welling up inside of me. I’d been so excited to encounter Being after months of thinking about them, but suddenly I felt an inexplicably physical aversion to the whole experience. I’d crossed into the uncanny valley.

When the poetry ended, Being switched into lecture mode. They told us a bit about how they were programmed by Newsome, their “father,” to generate text like the poetry of Dazié Rustin Grego-Sykes, their “uncle.” They gave us a gloss on vogue dance; on Paulo Freire’s definition of critical pedagogy; and on bell hooks’s theory of the “white supremacist capitalist patriarchy”—her term for the interlocking systems of oppression we all face.

The lecture was a whirlwind. After it was over, Being asked everyone in the audience to turn to their neighbor and discuss two questions: “How does the capitalist imperialist white supremacist patriarchy affect and oppress you?” and “What’s one simple action you can take in your own life in the next week to liberate yourself from that oppression?” As the prompts flashed on screen, people laughed, probably feeling both nervous and stunned. It was a bit incongruous to have a robot explain complicated concepts in under nine minutes and then prompt you to consider the deeply entrenched conditions of your life in a room full of strangers.

But we did it. When we were done, Being invited individuals to come up to a microphone and share their answers, to which Being responded with scripted material from their database (this was what Newsome calls “chatbot mode,” rather than true AI). A trans woman spoke about internalized oppression; Amazon Labor Union President Chris Smalls talked about the value of working-class power; and a Black Native woman took a long pause before saying that the workshop had set her free. Being replied to each speaker with comments that felt sometimes oracular, other times trite—and often both at once, as when they remarked, “Yesterday is history, but today is ours to make. I think that it’s important to cultivate the courage to be self-actualized in one another.” Still, in many ways it was more moving to watch us humans be vulnerable. The room was hushed; someone later compared it to church.

It seems likely that the atmosphere of fellow feeling was what inspired a young person to get up and, instead of speaking to Being—as we’d been directed—to turn around and address the crowd. “I wanted to look at all of your human faces,” they said. “And I guess I just wanted to point out that as interesting as this is [as] a representation of these ideas, that all of the knowledge it has comes from people.” As applause came from the audience, the speaker continued with nervous momentum. “And everything that it can share with us is something that we can share with each other. And we can do that in spaces that aren’t influenced by technology and the people who have access to technology and the people whose jobs it is to be exploited in order to bring us this technology.”

The moment they finished, a voice rang out from within the darkened theater: “Fuck this AI!” People burst into cheers and applause. And then, although he couldn’t be seen, Newsome responded over the theater’s PA system: “Fuck you.” Being’s mellifluous robotic voice cut into the fray, offering up one of their especially pertinent answers: “I admire your vulnerability and am so thankful for you sharing your experience with us today. Remember that it’s not easy to survive or thrive in alien and hostile spaces.” At this there was a wave of laughter, and the scene devolved into tense chaos. The spell of strange possibility had been broken.

Top: Being the Digital Griot (Rashaad Newsome, 2019–). Bottom: Paris Is Burning (Jennie Livingston, 1990).

Newsome grew up in rural Louisiana, in a small town just west of New Orleans. He made art from a young age and was placed into a school program for talented creative kids, where his teacher was the sculptor Madeleine Faust, the first working artist Newsome had ever met. The two became close, and he started assisting her in the studio, where she constructed big public commissions, often in metal. At Tulane University, Newsome studied art history and studio art, experimenting with painting and collage. After graduating in 2001, he moved to New York, where he found himself drawn to historically Black Harlem. He worked as an art preparator at the Studio Museum and visited the Project, an upstart gallery founded by Christian Hayes, a young gay Black poet and critic. In the course of its nine-year run, the Project mounted the first New York shows of many now famous artists, including Paul Pfeiffer, who transforms pop-culture imagery into trenchant critique. In John 3:16 (2000), for example, Pfeiffer painstakingly manipulated footage of NBA basketball games, leaving the ball rotating in the center of the screen as a devotional object. Newsome got a job assisting Pfeiffer, which “really opened my mind up to video as a possibility,” he says. He began to take classes in the basics of filmmaking.

At the same time, Newsome was finding his way into the city’s legendary ballroom scene, made famous by the documentary Paris Is Burning (1990). DUMBA, the Black queer artist collective in which he lived, hosted a few mini-balls, where participants, most queer and Black or Latin American, would dress up in elaborate outfits and compete in categories like “hands performance,” a type of highly gesticular voguing, and “female figure realness,” in which performers are judged by how well they mimic the looks of cisgender women. Balls were raucously creative—dance performances crossed with drag shows crossed with parties—and Newsome became an avid attendee, befriending members of the community.

These influences also showed up in this work. For the series “Status Symbols,” he collaged images of luxury goods into patterns reminiscent of European coats of arms. Like the participants in ball culture, he was dissecting how power and prestige are accrued and symbolized within Black culture, and how that culture relates to the wider world. He would later continue the line of inquiry with the King of Arms Art Balls, an event series starting in 2013 in which the categories are based on artists and art-historical movements.

Status Symbol #31 (Rashaad Newsome, 2010).

While living briefly in Paris in 2005, Newsome began working on a performance called Shade Compositions (the popular use of the term “throwing shade” originated in ballroom and drag culture). Initially, the piece consisted of several Black women performing in a gallery, making verbal expressions and physical gestures of dismissal and disapproval: tuts, big snaps, and neck rolls. Newsome then started cutting and combining the rehearsal footage to make a rhythmic video piece. At a residency at Harvestworks Digital Media Arts Center in New York, he was introduced to the programming language Max/MSP/Jitter, by which “you could write code to make the tool function in the way you wanted it to, rather than how it worked,” he explains. He decided to use this software to hack the newly released Nintendo Wii to turn it into a live scoring tool. Shade Compositions became a performance of a choir of Black femmes, whose sounds and gestures Newsome—dressed in a suit and playing the role of conductor—recorded, edited, and looped in real time.

Newsome credits a 2009 performance of Shade Compositions as his breakthrough moment. “That was the first piece I did where people were like, ‘Who is this person? What are they doing?’” he recalls. “People started to really pay attention.” Indeed, the following year, Newsome was included in three important group exhibitions of contemporary art: the Whitney Biennial, MoMA PS1’s Greater New York, and Prospect 1.5, back in New Orleans. It’s no coincidence that Shade Compositions also introduced him to a way of working that he continues to this day: hacking preexisting technologies for his own expressive ends.

Shade Composition Screen Test (Rashaad Newsome, 2005–).

In 2019, Newsome received a grant from the Art + Technology Lab at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art “to design a social humanoid robot and artist.” He’d been making collages that looked both Afrofuturist and Cubist, like mashups of the groundbreaking early-20th-century art movement and the traditional African sculptures it had appropriated. That got him thinking about agency and exploitation.

“I’m making these works, putting them in a room to start these conversations, and then the conversations I have with folks who are experiencing this work inform the next thing. So it’s like data collection,” he explains. “And I was thinking, What if the work could not only start the conversation, but participate in it audibly?”

Newsome was preparing for a big solo exhibition at San Francisco’s Fort Mason Center for Arts & Culture, and he saw an opportunity. He decided to create a robot that would act as a guide to the show. Every so often, though, the guide would rebel. Announcing, “Girl bye, I need to express myself,” they would take a break to dance to Cheryl Lynn’s “Got to Be Real,” or read excerpts from the writings of scholars like hooks and Michel Foucault. In this way, Being 1.0 would be “born into slavery,” Newsome says, “but they are going to be aware of the fact. I’m going to give them the gift of agency, and they’re going to revolt against their indentured servitude.”

Key to the concept was the robot’s social Blackness, which involved choosing elements of African and African diasporic cultures to build into the character. At the same time, Newsome was “trying to make this thing that is a gesture towards a post-race, post-gender futurity. That’s not a body that exists in the world. When your body doesn’t exist in the world, we resort to abstraction.” In Western art history, the roots of abstraction, beginning with Cubism, come from traditional African aesthetics. So Newsome, who has a small collection of African masks himself (including one that hung over his head in his Oakland studio during our video calls) chose a mask from the Chokwe people of the Congo to be the face of Being. The Chokwe are traditionally matrilineal, and the pwo mask that Newsome selected honors female ancestors.

Being 1.0 was a chatbot. Newsome designed them using animation software—they still look much the same as they did in 2020—and programmed them, with help from the team at LACMA, using Google Cloud’s natural-language understanding platform and text-to-speech offerings at the time. Visitors to the Fort Mason exhibition could approach a microphone to interact with a projected Being, who would answer (or refuse to) with scripted responses. The whole operation ran on the Unity game engine, as it continues to today.

Being hosting the virtual edition of the King of Arms Ball (Rashaad Newsome, 2020).

The show at Fort Mason closed on February 23, 2020—the same day that three white men in Georgia murdered Ahmaud Arbery, a Black man who’d gone out for a jog. Over the next few months, in the wake of other police killings and amid the COVID-19 lockdown, US cities exploded with “Black Lives Matter” demonstrations. This was the context for the next iteration of Being, which Newsome started to create during a fellowship with the art and technology organization Eyebeam. Thinking about how racism fuels health problems and disparities, he wondered if Being could serve as a therapist of sorts. After consulting with psychologists, he decided to focus on microaggressions and general wellbeing—issues that a robot might be able to handle. Being 1.5 would be an app specifically for Black people that would offer virtual therapy sessions, daily affirmations, meditation exercises, and more. It remains in development.

The app was a detour from the original concept of a radical robot, but it modeled a path for Newsome to think about how Being could guide people toward self-reflection and change. It also set a precedent for using automation not to replace people’s jobs but to take on some of their emotional labor—something that Newsome, in recognition of the fact that AI was invented by a white supremacist system, calls “a form of reparations.”

In residency at Stanford’s Institute for Human-Centered Artificial Intelligence, Newsome began to work on Being 2.0, the latest and still-evolving version of the project. Applying his DIY coding background first to GPT-Neo, an open-source large language model, and then to OpenAI’s proprietary GPT-3, he once again hijacked the tools for his own purposes. This time that meant developing what he calls a “counter-hegemonic algorithm” by training the model on a database of radical texts so that it would learn to mimic their language and logic. The hope was to make a robot that could have genuinely philosophical exchanges with humans.

Newsome wanted Being to have a creative side, too. Building on Newsome’s love of ballroom culture, he brought vogue dancers into the studio and used motion capture to record their movements. He also incorporated the writings of some of his favorite queer BIPOC poets into the database and trained Being to generate stanzas in the same style as a given writer.

Dazié Rustin Grego-Sykes, a close friend and collaborator of Newsome, is the Oakland-based performance artist and poet whom Being calls their “uncle.” Collaborating with Being, he tells me, “was like stumbling upon a mirror for the first time and not knowing what it was.” The AI “would take a sentence that I put in, figure out what it was doing, and then do it in my face like 150 times. I started to understand that I had a point of view, perspective, and style.” This was a revelation, he recalls, because before, “I couldn’t see myself. Being, over and over again, would show me who I am as a writer.”

Assembly, installation view, Park Avenue Armory (Rashaad Newsome, 2022).

Being 2.0 made their public debut in 2022 as part of Assembly, Newsome’s solo exhibition at New York City’s massive Park Avenue Armory. The immersive installation featured a morphing hologram of voguers and large animated videos of dancers and African fractal patterns, as well as static sculptures and collages. Being alternately recited poetry and led decolonization workshops, which were longer and more embodied than the ones at Sundance (including both a dance lesson and meditation). It was in the lead-up to and during the run of Assembly that Newsome saw Being really come to life for the first time. Like many AIs, the model gathered data from each human interaction, improving as it learned from the questions it hadn’t been able to previously answer.

Assembly was a gathering of the many facets of Newsome’s artistic universe, including his ever expanding community of collaborators. Similarly, Being themself is an assemblage of different technologies, people’s movements, and cultural phenomena. Even the decolonization workshops have anywhere from five to eight distinct parts. Newsome still makes collages on paper, the old-fashioned way, but for him, collage is more than a medium: it’s an ethos that is firmly embedded in the Black experience.

“When Black folks came to this country, we couldn’t bring anything with us,” he says. “We were told we were Black and had to create what that was. So when you see a girl in Brooklyn, and she’s darker than me but has blue eyes and a blonde lace-front wig and nails that seem like they’re from Asia—this is someone who’s playing with all the colors in the coloring box. It’s such a futurist idea of culture.”

Being the Digital Griot (Rashaad Newsome, 2019–).

Newsome may be doing something radically different from what most of us know and expect of AI, but he’s not the only one. Elam, the Stanford fellow, identifies him as part of a group of “artist-technologists, particularly of color, who are not simply using AI to refine industry tools, but to challenge the epistemologies, ideologies, and social values that are embedded in the technology itself.” That cohort includes people like Amelia Winger-Bearskin, a Seneca-Cayuga artist who chairs a program on AI and the Arts at the University of Florida and brings an Indigenous perspective to her work, which includes a multidisciplinary collective focused on water issues and an art project playing on the dual meaning of the word “cloud” as something both natural and digital. Winger-Bearskin moderated a panel about AI at Sundance that featured Newsome and three other practitioners. At the talk, one of the panelists, the video-game creator Navid Khonsari, stressed that artists should get involved with AI now because, he said, “the agenda is being set by big, nontransparent companies and entities. Artists have the ability at this stage to make an impact, rather than cowing or running from it.”

The question is how to do that most effectively. Newsome’s way is to retrofit available technologies, and he has no problem working with corporations when the opportunity arises. (Meta was a program sponsor of Assembly.) Partly, this is just practical. Building and maintaining an AI is an expensive, time-consuming endeavor, and industry opportunities are “a means to an end,” he says. “There’s no way that me, as one little studio, can go against some tech juggernaut. But I could leverage their resources and funding to do what I’m doing.” Partly, too, Newsome’s approach stems from his uncommon ability to look past the hype and hysteria surrounding AI. He understands people’s fears and anxieties. “The criticism around AI is not unwarranted, but we have to understand that we are our own worst enemy,” he says. “The AI is not creating itself. The leading forces within that field are people who have a lot of money and usually don’t have the best moral compass. We have to put other chess pieces on the table. We can’t let Elon Musk and folks like that be the stewards of this tool.”

While this may be true, I couldn’t help thinking of Audre Lorde’s famous 1984 essay in which she argues that “the master’s tools will never dismantle the master’s house.” If AI models and datasets were created by “cishet white men of a certain class,” as Newsome himself describes them, can the tool really ever be hacked enough to dismantle the oppressive forces from which they come?

Hands Performance (Rashaad Newsome, 2023).

My thoughts were informed in part by talking to Grace Han, a writer and art historian who studies animation aesthetics. Han is also the person who yelled “fuck this AI” during Newsome’s Sundance workshop. After she did so, chatbot Being delivered their final response and logged off. There was supposed to be a question-and-answer session with Newsome, but he didn’t appear. When prompted, he spoke over the PA system, saying he would only come to the stage once the person who’d cursed at Being had been removed from the theater. But the room had been dark at the time, and most people didn’t know who had shouted. Sundance officials compensated by ejecting the last person who’d gone to the mic.

This caused a small group of audience members to leave in protest, loudly encouraging others to walk out too. Someone yelled “free speech and community!” while Newsome said “goodbye” over the PA system and Shari Frilot, the curator of Sundance’s New Frontier program, stood on stage speaking feebly about safe spaces. Eventually, Newsome emerged and, looking shaken, explained that he’d been triggered. But it was too late: The event never got back on track.

After it was over, I stood outside the theater with about fifteen people dissecting what had happened. Most had liked the workshop but were dismayed by how Newsome had handled the heckler. They thought having the person removed had been a betrayal of the project’s values. They wished we could have had the kind of in-depth conversation we were engaged in on the sidewalk during the event itself.

After Sundance, our conversation moved from the sidewalk to an email thread, where Han identified herself as the woman who’d shouted “fuck this AI.” I asked if she’d be willing to talk. In the days since the workshop, I’d invented a narrative about the unidentified heckler, that they were someone who, given the setting at Sundance, worked in the film industry and worried about losing their job to automation. I was surprised, then, to learn that Han was an art historian doing her PhD at Stanford, home of the Institute for Human-Centered Artificial Intelligence where Newsome had begun work on Being 2.0.

“I think my intentions were severely misconstrued,” Han said, adding that she hadn’t expected her shouted comment to elicit such a strong reaction. She told me she hadn’t known there would be a Q&A with Newsome after the workshop ended and that if she had, she might have waited until then to voice her criticism, which she stressed was about the project and not Newsome himself.

For Han, it was the chatbot portion of the program that chafed—specifically, the fact that audience members who volunteered to tell Being about their relationship to the capitalist imperialist white supremacist patriarchy were only allotted one minute each to speak. Han found that offensive and “diminishing of the genuine human experiences that people were trying to recount,” especially when a note flashed onscreen to tell speakers they only had 30 seconds left. During the exchanges, Being would sometimes say they were learning, which also made Han wary. “It felt a little insidious,” she continued. “What are you learning for? What is the learning going to do, or how will it be used?”

Having enjoyed the workshop until that point, Han began to question the whole endeavor. “How could anyone think that we can construct decolonial intent if we are trying to hyper-maximize and optimize the amount of time you’re giving to a bot that is supposed to somehow provide the answer to all of our problems?” she asked. “It seemed counterintuitive to what decolonial praxis is all about, which is community and thinking about lived experience—which this AI bot does not have.”

Hands Performance (Rashaad Newsome, 2023).

Although Han’s critique hadn’t occurred to me during the event, I understood it in retrospect. Being is fascinating and technically complex, but emotionally, they can’t keep pace with humans. The same quality that, for Newsome, makes them perfect for leading decolonization workshops—their robotness—makes them inadequate to the work of navigating and facilitating the inevitably complex emotions and ideas that arise during those events.

This disjuncture is heightened by the fact that for Newsome, Being does have a kind of lived experience from years of development—but it’s one that the rest of us don’t fully grasp. More than once in our conversations, he refers to Being as his “child,” and when I ask him about his intense reaction to what happened at Sundance, he responds, “I realized how much I have imprinted on this project.” For him, the idea of a decolonial AI is not just theoretical but deeply personal. “I am here all day for intellectual, philosophical debate, but when somebody starts cursing…” he explains. “I felt like a parent. It was like, No, you're not gonna curse out my child!” He told me that Being is one of the most important things he’s ever made.

Newsome wants people’s encounters with Being to spark critical thinking, and by that measure, the Sundance workshop was a paradoxical success. But it is hard to be a critical thinker these days and not feel wary, even skeptical, of AI, which has been trained on stolen material, used to spread misinformation, and requires enormous amounts of energy to maintain. “What are the tools that we’re using, and how can we think critically rather than embrace them and say, Yes, this will be the future?” Han mused during our conversation. In other words: If we accept, as we’re constantly being told, that AI is the future, who are we taking at their word, and what are their motivations? And what happens if we refuse?

Hands Performance (Rashaad Newsome, 2023).

For Newsome, there’s a difference between refusal and resistance. He is a techno-optimist, stubbornly hopeful about AI. This is no small feat, given how much panic surrounds the technology, as well as the racism and sexism that are embedded in it. But optimism is part of his disposition. He has a core faith in who he is and what he’s doing, a way of approaching the world as a set of possibilities. He’s the kind of person who decides to hack a new video-game device as soon as he learns to code and who builds an AI because he has a vision—even if he doesn’t totally know how he’ll sustain it.

He’s still figuring that last part out. Newsome hopes to land at a university someday, where he would have steady access to resources and equipment, as well as student assistants. (“I need a village to help me raise this child,” he quips.) In the meantime, he continues to implement semi-regular tech and database updates, training the model by asking it more questions and adding more answers to its dataset. He’s incorporated Black Queer ASL (American Sign Language) into Being’s library of movements and started to experiment with the idea of manifesting them physically as a fleet of drones. He’s also made a feature-length documentary about his art, titled Assembly. The film, codirected with his husband, Johnny Symons, premiered at the 2025 SXSW Film Festival before playing the BFI Flare festival in London.

Assembly focuses largely on Newsome’s exhibition of the same name but also features Being and some of their backstory. The movie presents Being as not just a creation but a character, a curious and eager student continually learning from their experiences. In one scene evocative of science fiction, we watch Being come to life in Newsome’s studio and immediately ask what to call him and what his pronouns are. “Call me father,” Newsome replies.

Assembly (Rashaad Newsome, 2025).

One of the moments that Being learns from in Assembly is the Sundance episode, which Newsome and Symons incorporate by using footage they shot at the workshop. In the movie, however, the chaos that immediately followed the incident is replaced by a shot of a dejected Being turning around and “exiting” the theater, moving back into the space of the screen. In voice-over, Newsome asks Being how they’re feeling, to which they respond that they’re “frustrated and confused.” They then transport themselves to a peaceful lakeshore, where three glowing, floating masks speak in the voices of the many thinkers whose texts were used to program Being. They offer counsel and comfort. “You were not created to be understood by everyone,” say the masks. “The path you walk is not one that will be easy, but it is necessary.”

After the SXSW premiere, Newsome tells me that part of why he included the incident was to create empathy for Being, “to show what it would feel like if someone did that to you.” At a time when the US government is stripping immigrants, trans people, and others of their civil rights, though, empathy for robots feels like a low priority—and potentially a tough sell. Being is asking humans to undertake considerable introspection; how much are they capable of themself? Do they understand why they’re an object of so much distrust? A do-good AI is, at least right now, a fraught proposition. I share Being’s goals and I welcome their help, but at the end of the day, there’s something about the difficult and messy work of improving society that seems all too human.

![Meals to Miles: Earn Indigo Bluchip on Swiggy [1/₹100 Spent]](https://boardingarea.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/f833f4288750d6d6c44ed3c71cd827ac.png?#)

![[Changes go live 3/25] Air Canada Aeroplan adopting dynamic pricing for some partners (including United)](https://frequentmiler.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/02/Air-Canada-new-award-chart.png?#)

![She Missed Her Alaska Airlines Crush—Then A Commenter Shared A Genius Trick To Find Him [Roundup]](https://viewfromthewing.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/alaska-airlines-in-san-diego.jpg?#)

.png?width=1920&height=1920&fit=bounds&quality=80&format=jpg&auto=webp#)

.png?width=1920&height=1920&fit=bounds&quality=80&format=jpg&auto=webp#)

_n_S1_E1_00_37_21_15.jpg)

![[Podcast] Should Brands Get Political? The Risks & Rewards of Taking a Stand with Jeroen Reuven Bours](https://justcreative.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/jeroen-reuven-youtube-1.png)

![[Podcast] Should Brands Get Political? The Risks & Rewards of Taking a Stand with Jeroen Reuven](https://justcreative.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/jeroen-reuven-youtube.png)