One Shot | “Uncle Buck”

One Shot invites close readings of the basic unit of film grammar.Uncle Buck (John Hughes, 1989).John Hughes’s 1980s were a perfect storm. He was incredibly productive—he wrote the first 50 pages of Ferris Bueller’s Day Off (1986) in a single sitting—at the exact moment when his personal vision dovetailed nicely with the studios’ commercial sensibilities. He became the quintessential teen-movie auteur, writing and genre-defining films like Sixteen Candles (1984), The Breakfast Club (1985), and Pretty in Pink (1986), the first two of which he also directed. He didn’t mind making comedies about adult characters, too, particularly if they were played by John Candy. Many of Hughes’s films in this period were instantly beloved by audiences, but critics remained sniffy even in their praise. They estimated Hughes as, at best, a talented craftsman. He came to spend the 1990s as a writer-for-hire churning out increasingly bland and impersonal kids’ movies—including Dennis the Menace (1993) and the live-action 101 Dalmatians (1996)—unable to get his passion projects off the ground, before disappearing from public life altogether. John Hughes has gained cinephile credibility over the years, lauded by such filmmakers as Sofia Coppola and Greta Gerwig, and much of his work has endured as cultural touchstones of adolescence, speaking afresh to the growing pains of each new generation. But even this renewed appreciation has mostly focused on Hughes as a screenwriter, not a director. It’s true that some of his best-loved films were directed by other people—including Pretty in Pink (1986) and Home Alone (1990)—but it’s a mistake to neglect his directorial talent. The museum sequence in Ferris Bueller’s Day Off is about the power of artistic composition and a demonstration of Hughes’s acute attention to the same. Inspired by the director’s own youthful sojourns to the Art Institute of Chicago, the sequence frames even static shots of particular artworks in a way that emphasises their environment, their proximity to other artworks and to the people around them, giving you a sense of not just what’s in the museum, but how it feels as a space. Cameron’s existential crisis in front of A Sunday on La Grande Jatte by Georges Seurat, when he stares into a child’s face until it disaggregates into unidentifiable pointillist dots, is a masterstroke of conveying psychology through cinema, intercut with a breathtaking shot of Ferris and Sloane kissing in front of Marc Chagall’s America Windows. Uncle Buck (1989) is almost a dry run for Home Alone, a film whose wild success Hughes would try (and fail) to repeat throughout the second half of his career. Buck is Hughes’s first true family fare, stars Macaulay Culkin, and is about children at home without their parents—though they are nominally supervised. Candy plays the titular role, the bourgeois family’s cigar-smoking, habitual-gambler black sheep, who is called in to look after his brother’s children in an emergency. Gaby Hoffmann and Culkin play precocious siblings Maizy and Miles. Their teenage sister, Tia (Jean Louisa Kelly), resents her parents, this suburb, and the world. Tia is a bridge from Hughes’s teen movies to his family films: From her wide-brim winter hat to her fur-lined boots, with a backpack slung over one shoulder, she is a classic Hughesian protagonist. And indeed, despite the title, Tia is the film’s true protagonist, with Buck catalyzing her emotional journey toward reconciliation with their family. The starting point of that emotional journey is established in an opening sequence that frames the three kids as isolated from each other and their parents. Tia, Maizy and Miles are each portrayed separately coming home to the stately family home, with its arched gateway at the top of the front garden. Tia walks along an oak-lined footpath; Maizy arrives by bus; Miles runs through a neighbor’s garden, framed by slat wall panels and white picket fencing. Each kid occupies center frame, and the editing favors sharp perpendiculars—shots framed at right angles to the last—both touches that would become key elements of Wes Anderson’s trademark style. Maizy’s entrance, in particular, evokes the same kind of pictorial whimsy that Anderson would perfect. In Tia’s entrance, the trees give the field some depth; in Miles’s, the retreating handheld camera creates the sense of being jostled around. But Maizy’s entrance has a two-dimensional, storybook effect: a yellow school bus enters from the left, its horizontal lines at right angles to the archway’s supporting walls. The bus parks so its door lines up perfectly with the house’s front path. The geometry is as rigid and transcendent as a Piet Mondrian painting. Maizy climbs out, bundled up warm in clashing primary colors, eyes intent on the ground. Her form is a joyful, jarring interruption to this unbending world, like a stray daub of pigment. She starts up the path and through the archway, hopping from foot to foot, avoiding slip

One Shot invites close readings of the basic unit of film grammar.

Uncle Buck (John Hughes, 1989).

John Hughes’s 1980s were a perfect storm. He was incredibly productive—he wrote the first 50 pages of Ferris Bueller’s Day Off (1986) in a single sitting—at the exact moment when his personal vision dovetailed nicely with the studios’ commercial sensibilities. He became the quintessential teen-movie auteur, writing and genre-defining films like Sixteen Candles (1984), The Breakfast Club (1985), and Pretty in Pink (1986), the first two of which he also directed. He didn’t mind making comedies about adult characters, too, particularly if they were played by John Candy. Many of Hughes’s films in this period were instantly beloved by audiences, but critics remained sniffy even in their praise. They estimated Hughes as, at best, a talented craftsman. He came to spend the 1990s as a writer-for-hire churning out increasingly bland and impersonal kids’ movies—including Dennis the Menace (1993) and the live-action 101 Dalmatians (1996)—unable to get his passion projects off the ground, before disappearing from public life altogether.

John Hughes has gained cinephile credibility over the years, lauded by such filmmakers as Sofia Coppola and Greta Gerwig, and much of his work has endured as cultural touchstones of adolescence, speaking afresh to the growing pains of each new generation. But even this renewed appreciation has mostly focused on Hughes as a screenwriter, not a director. It’s true that some of his best-loved films were directed by other people—including Pretty in Pink (1986) and Home Alone (1990)—but it’s a mistake to neglect his directorial talent. The museum sequence in Ferris Bueller’s Day Off is about the power of artistic composition and a demonstration of Hughes’s acute attention to the same. Inspired by the director’s own youthful sojourns to the Art Institute of Chicago, the sequence frames even static shots of particular artworks in a way that emphasises their environment, their proximity to other artworks and to the people around them, giving you a sense of not just what’s in the museum, but how it feels as a space. Cameron’s existential crisis in front of A Sunday on La Grande Jatte by Georges Seurat, when he stares into a child’s face until it disaggregates into unidentifiable pointillist dots, is a masterstroke of conveying psychology through cinema, intercut with a breathtaking shot of Ferris and Sloane kissing in front of Marc Chagall’s America Windows.

Uncle Buck (1989) is almost a dry run for Home Alone, a film whose wild success Hughes would try (and fail) to repeat throughout the second half of his career. Buck is Hughes’s first true family fare, stars Macaulay Culkin, and is about children at home without their parents—though they are nominally supervised. Candy plays the titular role, the bourgeois family’s cigar-smoking, habitual-gambler black sheep, who is called in to look after his brother’s children in an emergency. Gaby Hoffmann and Culkin play precocious siblings Maizy and Miles. Their teenage sister, Tia (Jean Louisa Kelly), resents her parents, this suburb, and the world. Tia is a bridge from Hughes’s teen movies to his family films: From her wide-brim winter hat to her fur-lined boots, with a backpack slung over one shoulder, she is a classic Hughesian protagonist. And indeed, despite the title, Tia is the film’s true protagonist, with Buck catalyzing her emotional journey toward reconciliation with their family.

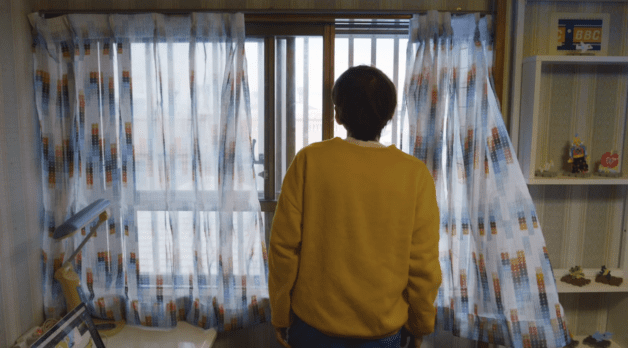

The starting point of that emotional journey is established in an opening sequence that frames the three kids as isolated from each other and their parents. Tia, Maizy and Miles are each portrayed separately coming home to the stately family home, with its arched gateway at the top of the front garden. Tia walks along an oak-lined footpath; Maizy arrives by bus; Miles runs through a neighbor’s garden, framed by slat wall panels and white picket fencing. Each kid occupies center frame, and the editing favors sharp perpendiculars—shots framed at right angles to the last—both touches that would become key elements of Wes Anderson’s trademark style.

Maizy’s entrance, in particular, evokes the same kind of pictorial whimsy that Anderson would perfect. In Tia’s entrance, the trees give the field some depth; in Miles’s, the retreating handheld camera creates the sense of being jostled around. But Maizy’s entrance has a two-dimensional, storybook effect: a yellow school bus enters from the left, its horizontal lines at right angles to the archway’s supporting walls. The bus parks so its door lines up perfectly with the house’s front path. The geometry is as rigid and transcendent as a Piet Mondrian painting. Maizy climbs out, bundled up warm in clashing primary colors, eyes intent on the ground. Her form is a joyful, jarring interruption to this unbending world, like a stray daub of pigment. She starts up the path and through the archway, hopping from foot to foot, avoiding slipping on patches of ice, but making a game of it, too. Where her older sister experiences the straight, sharp lines of their world as a constriction, a visual manifestation of carefully manicured conformity, for Maizy they are the diagram for uninhibited play.

![‘Wicked For Good’ & ‘Jurassic World Rebirth’ Look Massive For Universal Pictures [CinemaCon]](https://cdn.theplaylist.net/wp-content/uploads/2025/02/12165521/WickedSunset.jpg)

![‘Five Nights At Freddy’s 2’ Teaser Revealed & ‘How To Train Your Dragon 2’ Announced For 2027 [CinemaCon]](https://cdn.theplaylist.net/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/02205821/Screenshot-2025-04-02-at-8.57.40-PM.jpg)

![Benecio Del Toro Runs ‘The Phoenician Scheme’ & Emma Stone Gets Shaved In ‘Bugonia’ For Focus Features [CinemaCon]](https://cdn.theplaylist.net/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/02214210/EmmaStoneOscars2025.jpg)

.jpg?width=1920&height=1920&fit=bounds&quality=80&format=jpg&auto=webp#)