Drowning Dry Director Laurynas Bareiša on Finding Comedy in Tragedy, Nicolas Roeg, and the Things We Can’t Process

Conan O’Brien can be forgiven for quipping “Over to you, Estonia” after Flow won Latvia its first Oscar last month. The concept of a shared Baltic Cinema is still a relatively obscure one: “We have this complicated identity, culturally,” Laurynas Bareiša explained to me recently at the Riga International Film Festival in a cozy corner […] The post Drowning Dry Director Laurynas Bareiša on Finding Comedy in Tragedy, Nicolas Roeg, and the Things We Can’t Process first appeared on The Film Stage.

Conan O’Brien can be forgiven for quipping “Over to you, Estonia” after Flow won Latvia its first Oscar last month. The concept of a shared Baltic Cinema is still a relatively obscure one: “We have this complicated identity, culturally,” Laurynas Bareiša explained to me recently at the Riga International Film Festival in a cozy corner of one of city’s oldest cafes, “because we’re not part of the Slavic world and we’re not geographically Scandinavian, but I think there’s a sense developing of this Baltic region.” If a wave is forming in that part of the world, Lithuanian filmmakers have been at its forefront––at least since Bareiša’s debut, Pilgrims, won Venice’s Orizzonti section in 2021.

That success has since been bolstered by films like Marija Kavtaradzė’s Slow (a winner at Sundance in 2023) and the remarkable sweep of awards in Locarno last year, where Best Film went to Saule Bliuvaite’s Toxic and the directing and performance awards to Bareiša’s latest, Drowning Dry. “When I won in Venice, everybody was a bit shell-shocked in the filmmaking community. And I think now, after Maria and Saule, people are getting the feeling that they can go out and get seen.”

Set on a timeline that jumps around like a misremembered dream, Drowning Dry follows two sisters and their respective families on a fateful retreat to a lakeside summerhouse. Through macho posturing of the husbands, one of whom is an MMA fighter, Bareiša sets a mood of general unease that lingers towards a tragic event. Yes, it’s another film about trauma, but the director undercuts the gloom with flashes of humor, a sharp edge of mystery, and a wonderfully lean and compelling framework that leaves you wanting more than its 88 minutes.

Over a similarly swift half-hour (condensed and edited here for clarity), Bareiša spoke to us about fragile masculinity, filmmaking influences, and how close he came to using two songs by Atomic Kitten.

The Film Stage: The title refers to a condition where someone appears to survive a drowning only to suffocate back on land. Back in Locarno, you spoke about how this condition inspired the structure of the film itself. Can you unpack that a little?

Laurynas Bareiša: This condition, dry drowning or secondary drowning, felt to me like a metaphor for the social interactions the characters have. They have connections, but they’re suffocating. Both couples are going through the motions of it, with their relationships deteriorating more and more. It reminded me of this somehow––like there’s no water but you kind of suffocate anyway.

The timeline jumps around a lot throughout. I was curious: what was the first scene you wrote?

The first scene was the drowning situation, where the father takes out his daughter but doesn‘t perform CPR. And then he gets pushed away and another person saves his kid. It kind of hit me when I thought, “What if you don’t say thank you?” You know, what if you cannot say thank you? That related to a lot of things that I could see around me, this inability, especially for men. It’s like a lot of things that you see in society. You can say, “Oh, this is stupid,” but this is actually very deep inside. These are very problematic things that we are not able to process. So out of that, I started writing this structure.

So it almost builds from the middle out?

Yeah, because this is the moment where time splits. You know, it’s a traumatic event. And all four of them are like different aspects of how you deal with this one situation. Like, one character is obviously very external and physically able and can react instantly, but also he’s very closed-off and doesn’t see everyone around him. This is Lucas, the fighter: he doesn’t understand that his wife doesn’t like the way he’s acting towards her and how everybody feels around him. But the other husband is very conscious how everybody sees him. He gets stuck in these moments that are very important, but he’s unable to move because of it. And then the sisters: one is very distant and already defeated somehow, psychologically, but the other one, who you think this is hardest for, she’s the strongest mentally. She’s very resilient and has ways to cope. So I decided to make this square.

So I wanted to explore the relationship to this tragic event and how you keep coming back and how differently you experience it. There’s a lot of similar scenes, or even the same scenes.

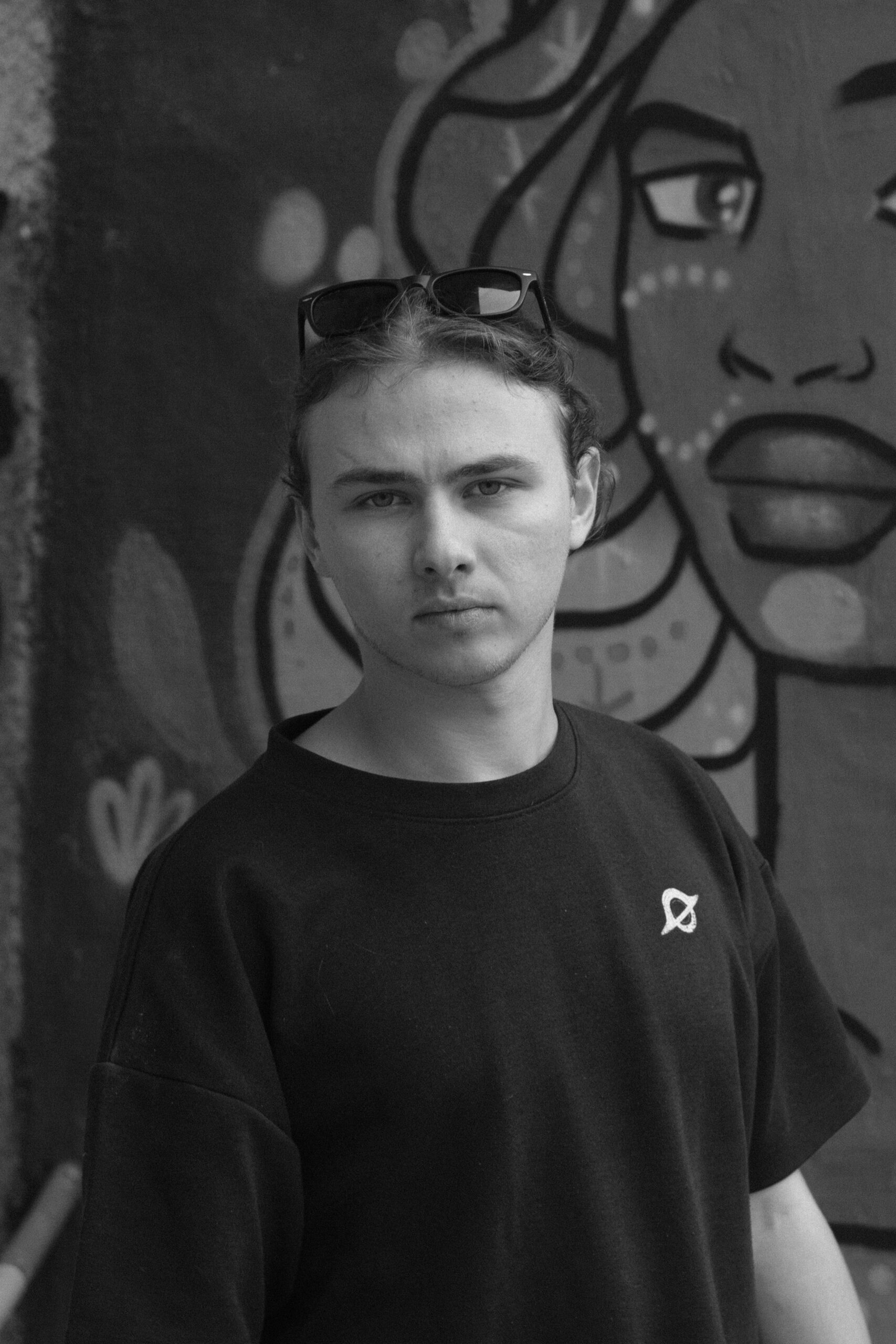

Laurynas Bareiša at Locarno Film Festival

You show the sisters dancing twice, and each time to a different song. How did you choose them?

I just had them stuck in my head from the 2000s, from MTV time. I kind of figured that the two sisters are kind of a similar age and also grew up watching the same channel. The first two songs I chose were by Atomic Kitten, “Eternal Flame” and “Whole Again,” but the problem was that people wouldn‘t distinguish they were different songs. They’re from the same album, but if you listen to it you’re kind of not conscious when one song ends and another begins.

But the dance is the exact same. Did you even shoot it twice?

The fighting shot is the same but the dance is not. You can see that they are mouthing the song and that’s where the mind fuck comes in. The funny thing is that we got the rights the day after the shoot, so we actually have, like, eight different songs performed. We got the ones that we wanted, but we have these shots with eight different ’90s hits.

You can put them on the DVD.

[Laughs] Yeah, like extra material.

There’s an incredible moment when Lukas tries to overtake a log truck on the motorway. How did you manage to shoot that? It’s like something out of Final Destination.

Yeah, every time I drive behind this kind of forest truck I’m thinking of that scene. But we had the stunt double and then we timed it with our actor. The first time he did it I almost puked myself because he didn’t understand my direction. He just went and overtook, so it was even more dangerous. But there were, like, three stunt drivers; only the truck had a truck-driver and all of the other cares were stunt drivers.

There’s a real sense of death throughout the film. Pilgrims also went for a similar mood.

With Pilgrims I kind of wanted to explore the physical space, like the geography of trauma––these kind of places where you know something bad happened. There’s no indication, but emotionally people feel very heavy. Pilgrims was borne from a short film I did about this gruesome murder, and we went to the real location. It was like a road in a forest, very simple. But you know what happened there so it becomes this kind of radioactive space. It kind of went into how the places where we live have layers of this history.

So I wanted to explore that again, but Drowning Dry is less physical and more about time, you know, how we kind of explore our traumatic events through repetition. How there are emotional facts and real facts and they sometimes get mingled. I wanted to explore that because with this film, I wanted to have some hope.

That’s something I really appreciate about the film: it never feels too weighed-down. There is hope, some grace notes, even some humor.

For Lithuanians especially, there are some inside jokes. Especially where they’re watching basketball on the laptop, it’s very funny for Lithuanians because you can hear the coach and he’s being very explicit––like “fuck this, fuck that.” It’s a very typical Lithuanian scene. We actually had some Lithuanian critics saying that, for the first 40 minutes, it’s a good family comedy.

And even after the death, the sisters are able to find things to laugh about. There’s this moment with the person who’s been saved by one of the organs.

That was the scene where I kept thinking, “Should I do this or shouldn’t I?”

It’s pretty shocking, but it really works.

It was a scene I hadn’t seen before and I wanted to do that. A mix between very sad and very awkward and very fucked-up.

You mentioned the idea of places being radioactive. You definitely get a sense of that, almost literally, at the ending here, with them revisiting the holiday home and all the food still sitting there.

I wanted to have something in the film you cannot control. So we decided to leave it there for a month-and-a-half and come back and see what happens. The art department made a cage so wild birds wouldn’t eat it, but otherwise we left it. We didn’t know what would happen, but I wanted this real object of time in the film. You can make mold as a prop, of course, but I wanted something I couldn’t fake or design because the film is very structured and conceptually driven.

Were there any filmmakers whom you looked to for inspiration?

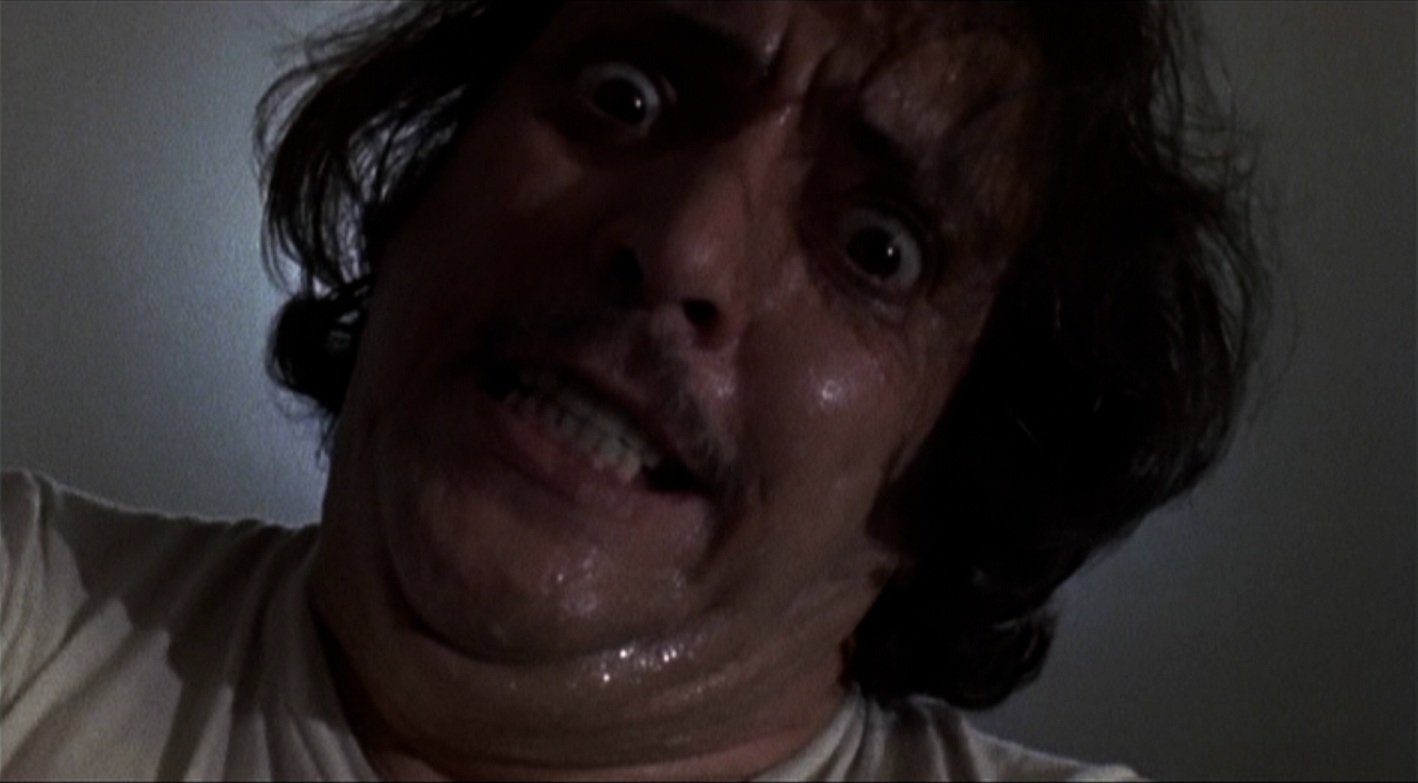

This film is very connected to Nicolas Roeg. This is of course not as intense, but I always loved the way the editing [in Don’t Look Now] jumped through time. Hong Sangsoo is also a filmmaker I jumped into several years ago. But they come and go, you keep watching and sometimes you experience something. There’s this Argentinian filmmaker, Eduardo Williams; he did Human Surge. I admire him a lot. Part 3 was in Locarno the year before. This is an experience you can still get in a film festival, where you just get totally out there, you know?

That’s right. It’s amazing when you’re reminded that there are things you haven’t seen yet.

Yes, because cinema has a tendency to normalize–even the festival-circuit stuff. So when you get these kinds of films it’s very inspiring.

Drowning Dry plays at New Directors/New Films on April 3 & 6 and will be released by Dekanalog.

The post Drowning Dry Director Laurynas Bareiša on Finding Comedy in Tragedy, Nicolas Roeg, and the Things We Can’t Process first appeared on The Film Stage.

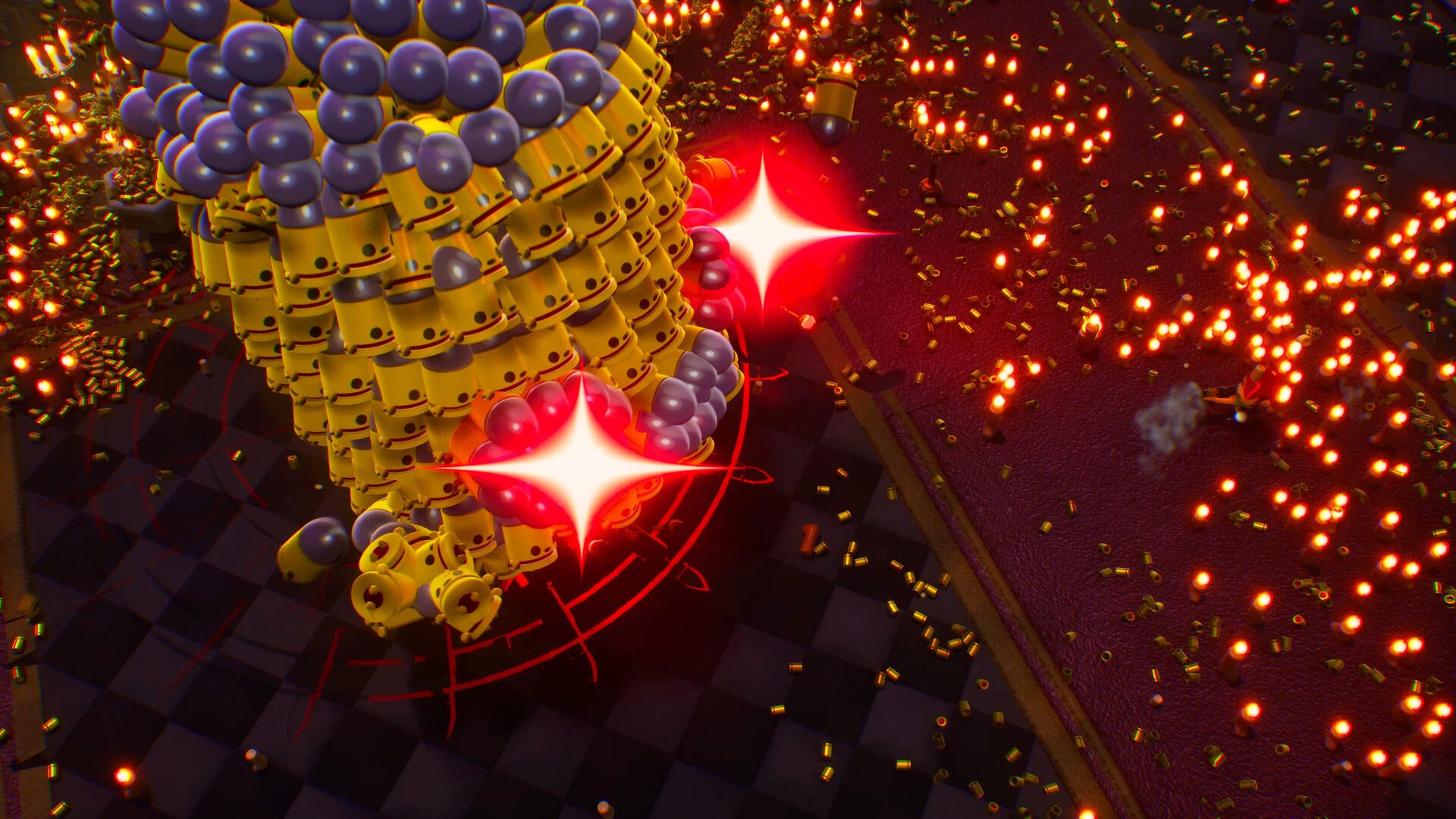

![“Tokyo Ghoul” and Ken Kaneki Now Available in ‘Dead by Daylight’ [Trailer]](https://bloody-disgusting.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/dbdtokyo.jpg)

![Extended: Buy Marriott Bonvoy Points with a 45% Bonus [0.86¢ or ₹0.74/Point]](https://boardingarea.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/46523d48a9dbea5cac3a9961201c257d.jpg?#)

![Miles & More Mileage Bargains Promo Awards [Apr’25]](https://boardingarea.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/335d951d4569e7d51813bc1c8be3a5d1.jpg?#)

.png?#)

.jpg?width=1920&height=1920&fit=bounds&quality=80&format=jpg&auto=webp#)