The Traveler and the World: Miguel Gomes’s “Grand Tour”

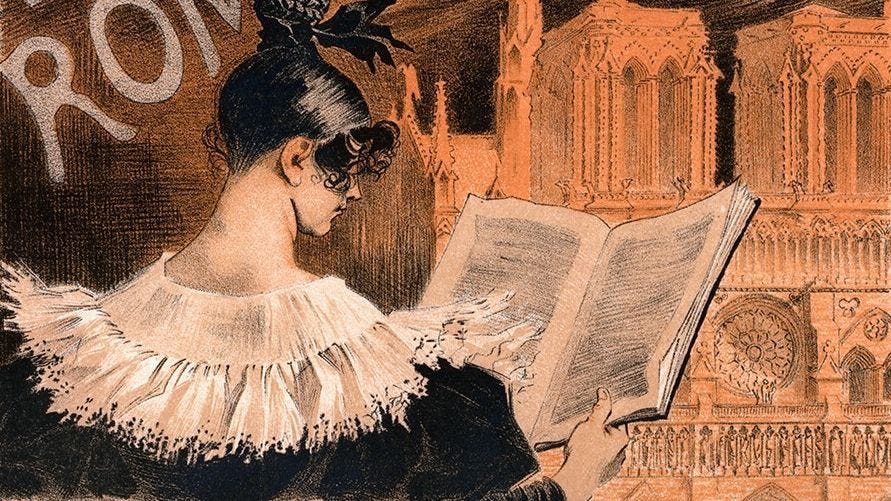

Miguel Gomes’s Grand Tour premieres in theaters on March 28 before coming to MUBI on April 18.Grand Tour (Miguel Gomes, 2024).Some years ago, I traveled nearly the length of Russia on the Trans-Siberian Railroad. That winter was warm, as nearly all are now, but a Siberian winter is still winter by any definition, and for two weeks I shivered my way from Ulaanbaatar to Moscow. I slipped on the vast frozen expanse of Lake Baikal, visited a museum dedicated to the painter Nicholas Roerich where all the paintings were fakes, saw a cathedral built atop the merchant house where in one night the entire Romanov line had been eliminated. On the leg from Irkutsk to Novosibirsk I shared a cabin with three men. I do not speak Russian, and for twenty-eight hours we managed to communicate via gestures and photos and sentence fragments ventured in halting English. They wanted to know where I was coming from, where I was going, whether I was thumbs-down or thumbs-up on Donald Trump. I shook my head and smiled. The oldest was named Mikhail, a loud, generous man in his late fifties or so who forced food on me and smoked with the lavatory window cracked. Half his suitcase was packed with lunch, and at one point he took out his phone to show me a photo of his granddaughter, then swiped past to linger over all the gold rings and hand grenades he had found with his metal detector. Whenever I came back in from the corridor with a mug of tea Mikhail would hand me a plastic cup of his 100 proof “home product” whiskey; according to my journal, I drank eight of them. I don’t know where Mikhail was from, what he did, why he was making the trip. But he sure got me good and drunk.Traveling is like this, a frequent negotiation of misconceptions and half-understandings that, with luck, can arrive at a kind of accidental truth. To go abroad is to leave one’s context and be immersed in the unusual, the unknown. For those open to it, these experiences can be vivid, even profound. Yet there is always a limit to understanding, a gap between the visitor and the world, and any bridge built across it is bound to be shaky. With Grand Tour (2024), Miguel Gomes makes this gap literal, never letting his travelers near the places they are meant to be. Edward (Gonçalo Waddington), a colonial official stationed in British Burma, is betrothed to Molly (Crista Alfaite). Theirs has been a long and long-distance engagement, and after a separation of seven years Molly has come to Rangoon to seal the deal. As Molly’s ship is coming in, Edward gets cold feet and boards another bound for Singapore, his fiancée following shortly behind. This journey takes one and then the other to Bangkok, Saigon, and onward eventually to China, a grand tour through an empire on the edge of dissolution. Their scenes in places like the Raffles Hotel and a rural Vietnamese estate take place on soundstages in Lisbon and Rome. These sets are lushly textured, densely detailed, and so plainly artificial that Gomes concludes his film with a shot of the crew concluding their work on Grand Tour. Grand Tour (Miguel Gomes, 2024).There is a gorgeous unreality to this fading colonial world, which Gomes only heightens with his free mixing of filmic language that references silent comedies, adventure films, and the French New Wave. Yet this is only half of his gambit. Though set in 1918, much of Grand Tour is made up of 16mm footage shot in the streets and forests and jazz clubs of contemporary Asia. Compared with the locked-down camerawork of the film’s fiction scenes, these images are fluid, handheld; the 16mm texture charges them with the excitement of life. A bamboo cutter goes about his careful work. A tour boat glides through the neon canyon of Osaka’s Dotonbori Canal. A man breaks into tears during a Tagalog performance of Frank Sinatra’s “My Way.” None of these passages have anything to do with Edward and Molly. Yet the film’s many narrators speak (always in the language native to the scene) as if they do, collapsing these pointedly contemporary images into a century-old narrative.Gomes told a similar story in Tabu (2012), staging a forbidden romance between Portuguese colonists on location in Mozambique. That film clothes independent Africa in the image of its colonial past, deploying contemporary locations as if they belonged still to the Portuguese empire. It’s an attempt at integration, at dressing the present up as the past. In Grand Tour, Gomes is constantly showing us one thing and telling us it is another, a disconnect between image and text (and even between text and text) that transforms the film from a light comedy of romantic manners into something considerably more expansive and destabilizing. Edward travels up the Yangtze on a car ferry. English officials speak Portuguese. A real ruin is a colonial outpost, because the narrator tells us it is. More than simple juxtapositions, these disjunctures engage in a kind of double movement, alienating image from image and then wea

Miguel Gomes’s Grand Tour premieres in theaters on March 28 before coming to MUBI on April 18.

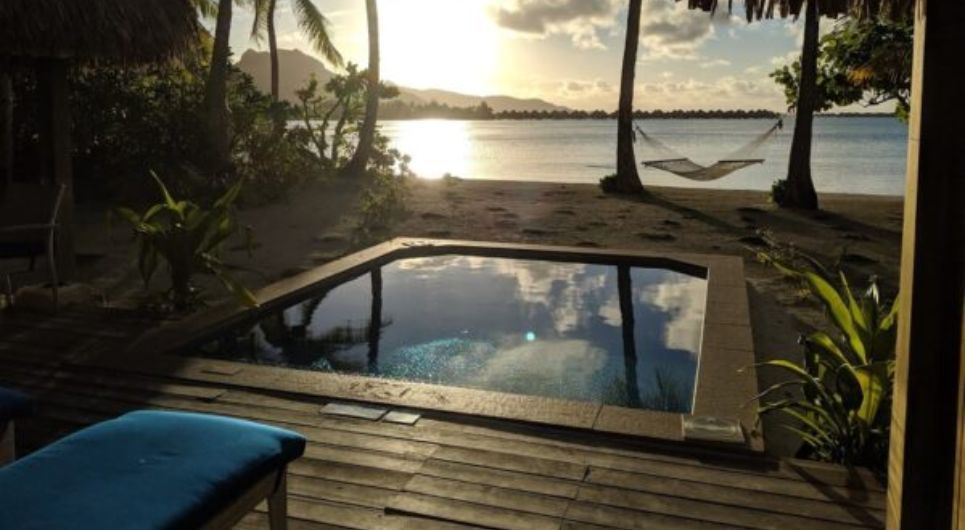

Grand Tour (Miguel Gomes, 2024).

Some years ago, I traveled nearly the length of Russia on the Trans-Siberian Railroad. That winter was warm, as nearly all are now, but a Siberian winter is still winter by any definition, and for two weeks I shivered my way from Ulaanbaatar to Moscow. I slipped on the vast frozen expanse of Lake Baikal, visited a museum dedicated to the painter Nicholas Roerich where all the paintings were fakes, saw a cathedral built atop the merchant house where in one night the entire Romanov line had been eliminated. On the leg from Irkutsk to Novosibirsk I shared a cabin with three men. I do not speak Russian, and for twenty-eight hours we managed to communicate via gestures and photos and sentence fragments ventured in halting English. They wanted to know where I was coming from, where I was going, whether I was thumbs-down or thumbs-up on Donald Trump. I shook my head and smiled.

The oldest was named Mikhail, a loud, generous man in his late fifties or so who forced food on me and smoked with the lavatory window cracked. Half his suitcase was packed with lunch, and at one point he took out his phone to show me a photo of his granddaughter, then swiped past to linger over all the gold rings and hand grenades he had found with his metal detector. Whenever I came back in from the corridor with a mug of tea Mikhail would hand me a plastic cup of his 100 proof “home product” whiskey; according to my journal, I drank eight of them. I don’t know where Mikhail was from, what he did, why he was making the trip. But he sure got me good and drunk.

Traveling is like this, a frequent negotiation of misconceptions and half-understandings that, with luck, can arrive at a kind of accidental truth. To go abroad is to leave one’s context and be immersed in the unusual, the unknown. For those open to it, these experiences can be vivid, even profound. Yet there is always a limit to understanding, a gap between the visitor and the world, and any bridge built across it is bound to be shaky.

With Grand Tour (2024), Miguel Gomes makes this gap literal, never letting his travelers near the places they are meant to be. Edward (Gonçalo Waddington), a colonial official stationed in British Burma, is betrothed to Molly (Crista Alfaite). Theirs has been a long and long-distance engagement, and after a separation of seven years Molly has come to Rangoon to seal the deal. As Molly’s ship is coming in, Edward gets cold feet and boards another bound for Singapore, his fiancée following shortly behind. This journey takes one and then the other to Bangkok, Saigon, and onward eventually to China, a grand tour through an empire on the edge of dissolution. Their scenes in places like the Raffles Hotel and a rural Vietnamese estate take place on soundstages in Lisbon and Rome. These sets are lushly textured, densely detailed, and so plainly artificial that Gomes concludes his film with a shot of the crew concluding their work on Grand Tour.

Grand Tour (Miguel Gomes, 2024).

There is a gorgeous unreality to this fading colonial world, which Gomes only heightens with his free mixing of filmic language that references silent comedies, adventure films, and the French New Wave. Yet this is only half of his gambit. Though set in 1918, much of Grand Tour is made up of 16mm footage shot in the streets and forests and jazz clubs of contemporary Asia. Compared with the locked-down camerawork of the film’s fiction scenes, these images are fluid, handheld; the 16mm texture charges them with the excitement of life. A bamboo cutter goes about his careful work. A tour boat glides through the neon canyon of Osaka’s Dotonbori Canal. A man breaks into tears during a Tagalog performance of Frank Sinatra’s “My Way.” None of these passages have anything to do with Edward and Molly. Yet the film’s many narrators speak (always in the language native to the scene) as if they do, collapsing these pointedly contemporary images into a century-old narrative.

Gomes told a similar story in Tabu (2012), staging a forbidden romance between Portuguese colonists on location in Mozambique. That film clothes independent Africa in the image of its colonial past, deploying contemporary locations as if they belonged still to the Portuguese empire. It’s an attempt at integration, at dressing the present up as the past. In Grand Tour, Gomes is constantly showing us one thing and telling us it is another, a disconnect between image and text (and even between text and text) that transforms the film from a light comedy of romantic manners into something considerably more expansive and destabilizing. Edward travels up the Yangtze on a car ferry. English officials speak Portuguese. A real ruin is a colonial outpost, because the narrator tells us it is.

More than simple juxtapositions, these disjunctures engage in a kind of double movement, alienating image from image and then weaving them all together through story. They attempt to evoke connections, even relationships, between the past and the present, the worlds of experience and fiction. As with the film’s many deployments of shadow puppetry and other performance arts, these gaps draw the viewer’s attention to how often in film one place is made to stand in for another, and how even documentary images are shaped and contextualized to maximize audience comprehension. The effect is stirring, exciting, and like all travel, deeply melancholy.

Top: Sans soleil (Chris Marker, 1983). Bottom: The Inland Sea (Lucille Carra, 1991).

In his determination to fictionalize nonfictional images, Gomes recalls the pioneering documentary work of Chris Marker, particularly Sans soleil (1983). Splicing footage captured in Japan, Guinea-Bissau, Cape Verde, and Paris together with clips of horror films, news images, and a photo-montage of Vertigo (1958), Marker creates something between travelogue and stream-of-consciousness collage. The narration is presented as a series of letters penned during the travels of a cameraman named Sandor Krasna, who reflects philosophically on the footage he has collected. His documentary material is intimately shot, its presentation is deliberately alienated by the arrival of fictional characters and jarring associations between seemingly unlike images. Marker is trying to dislocate the viewer, to unsettle their passive relationship to documentary evidence, and to show them that, in modernity, seemingly distant places can be intimately connected by supply chains, communication technology, the editor’s knife.

Marker collected his footage throughout the 1960s and ’70s, a period of rapid development and commercial growth in Japan. He focuses on department stores, crowded parades, advertisements, movies, and emerging technologies; the film ends with him feeding early scenes into a video synthesizer. Like any good avant-gardist, he was inspired more by the world’s transformations than by whatever world was in the process of being transformed, and when he does pay a visit to a temple or shrine it is to mark some peculiarly modernized ritual, like the burning of ready-made dolls at the Kannon temple in Ueno Park. Like the samurai in the chanbara movies he captures off the TV, these rituals have survived into the present, but in a profoundly changed form.

Whatever Marker’s misgivings about the ravages of modernity, his film sides ultimately with the transformed, the transformers: It is a movie told from the perspective of the future. He focuses on the “urban Japanese” scorned by the film writer and scholar Donald Richie as no longer really Japanese. In the late 1960s, Richie searched for them in the islands and cities around the nation’s Inland Sea, and in 1971 published a travelogue of the experience, which documentarian Lucille Carra would adapt as The Inland Sea (1991). Carra’s sublime film traces Richie’s earlier trajectory and sets the film to his words. Yet after twenty years, much has changed in Richie’s unchanging Inland Sea: The bridges he foresaw have been constructed, the remote island towns now draw tourists, and even Richie’s voice has aged considerably. The author’s narration celebrates places that seem to have held out against the bowdlerizing forces of modernity, but the filmmaker’s images tell a different story.

The Inland Sea documents a landscape, but also a series of gaps. Experience has become memory; the present is drawn inexorably into the past. Carra’s vision of contemporary Japan is now a record of a time before my birth. It expresses better than most the essential melancholy of travel: You can try to immerse yourself in the life of another place, but you remain always on the outside, an observer. Any record of travel is a record of change, and of loss, which even Richie acknowledges at the end. There are no “real Japanese” to be pinned in place and taxonomized. The object of his journey is a fantasy, a terminal where no one can disembark.

Chocolat (Claire Denis, 1988).

Such hazy fantasies fuel Claire Denis’s 1988 debut, Chocolat. A young woman named France has returned to Cameroon to visit the place of her childhood. France grew up in the north of French Cameroon, where her father was a colonial administrator—as was Denis’s. Her memories of the place are warm, vivid, enlivened by a closeness with the landscape, and especially with Protée, a Cameroonian house servant played by Isaach de Bankolé.

Protée cares for France, assists her father, and yearns for her mother, Aimée. Significantly, he mediates between the colonial household and the outside world, stranding him in an uncomfortable zone between the two. He is close with France, and she trusts him completely. But theirs is a provisional intimacy, a relationship with hard borders; and when France attempts a crossing, it scars them both for life. Aimée mediates her reciprocal attraction by commanding Protée around, giving him illogical orders, and belittling other such “house boys” in his presence. When she finally reaches out toward him, he knows better than to take the bait. The colonial home can only survive by keeping everyone in their proper place.

Upon her return, decades later, France is picked up on the road by a man named William, an African American who tells her a story about his first visit to Cameroon. William had arrived in Africa ready to be embraced by his people, as if arriving home. The border guards didn’t care; a cab driver ripped him off; and soon he was stranded, alone, in a country that he had once believed to be his birthright. The Africa of his imagination was always a mirage, but he has found nothing to replace it. The same is true of the Cameroon of France’s childhood, no less imaginary for having been actually experienced. She felt deeply at home in a place that was not really home; she can return to the ruins of the house in Mindif, but like Richie, like Marker, like Edward and Molly and perhaps like Gomes himself, the thing she is searching for is long gone.

Grand Tour (Miguel Gomes, 2024).

Film is often described as a transportive medium: Through the magic of the footage projected in a dark room, we can visit other places and times. At bottom, all images record a dead world, a world that is passing further away with every instant. During the pandemic, people around the world live-streamed their walks around empty cities. To view them now is to be transported to a near past that feels as if it occurred in another century—to realize that your own life can become distant to you, transformed into history.

Even the memories with which I began this essay have faded, become confused. There were two other men in the compartment, but I did not speak with them, and recorded only one of their names. And I had distinctly remembered looking out the window deep into my drinking spree and seeing a fox leaping across the steppe. But looking back through my journal, the red blur appeared against the white on another leg of the journey, after other drinks with other companions whom I don’t remember at all.

To see the world is to be overwhelmed by experiences, encounters, all manner of vistas, the real meaning of which you will never fully understand. Yet they live inside you, vivid still for being incomplete and obscure. I may have misplaced the memory with the fox, but I see him still racing alongside the tracks in the midst of that vast unspooling horizon.

![‘Zombie Army VR’ Shuffles to a May 22 Release; Pre-Orders Open Now [Trailer]](https://bloody-disgusting.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/zombiearmy.jpg)

![Tubi’s ‘Ex Door Neighbor’ Cleverly Plays on Expectations [Review]](https://bloody-disgusting.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/Ex-Door-Neighbor-2025.jpeg)

![Uncovering the True Villains of Gore Verbinski’s ‘The Ring’ [The Lady Killers Podcast]](https://bloody-disgusting.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/Screenshot-2025-03-27-at-8.00.32-AM.png)

OSAMU-NAKAMURA.jpg?width=1920&height=1920&fit=bounds&quality=80&format=jpg&auto=webp#)

.png?#)