A Friendlier Form of Bullfighting in the 'Wild West' of France

A dusty arena in the French village of Marsillargues seems like an improbable setting for Carmen. The crowd is dressed in patterned shirts and denim—Provençal rancher wear—instead of opera attire. Yet, when Bizet’s rousing song booms over the loudspeaker, the cheers aren’t for a robust tenor taking center stage, but rather a brawny black bull. This beast is the star of a centuries-old tradition in the southern region known as the Wild West of France. Straddling sport and spectacle, the course camarguaise is a friendly, not fatal, affair that blends small-town rodeo with Spanish corrida. Unlike bullfighting, in which man and beast engage in a dance that is destined to end in the animal’s demise, the choreography of the course camarguaise showcases the bulls' might without endangering their lives. Young men (and, on some occasions, women) dressed in white, called raseteurs, run at a bull to nab prizes affixed to his head and horns. When the bull charges, they jump out of the arena to avoid sharp horns that can pierce their skin “like a knife slicing through butter,” says Benjamin Villar, a champion raseteur who now dedicates his time to training. The course camarguaise is named for the rugged region where it was invented: the Camargue. Whipped by gusty winds, Europe’s largest wetland sits where the Rhone River spills into the Mediterranean Sea. The Camargue’s wild mosaic of fields, marshland, and salt flats are peppered with a unique mix of pink flamingos, ivory horses, and ebony bulls. There are nearly twice as many cattle as humans in the region. These are Camargue cattle, or Raço di Biòu, a domestic breed that is raised in semi-feral conditions in the marshes. The bulls, which can weigh over 800 pounds, are revered like kings. “The bulls get top billing on the marquee at the course camarguaise,” says Villar. Statues of bulls stand proud in towns that have arenas. The most victorious are buried standing up, their heads turned towards the sea. In his 1994 book on bullfighting in the Camargue and Andalusia, the anthropologist Frédéric Saumade writes how locals “Have a genuine faith…and love…for the untamable biòu.” This fé de biou (“faith in the bull” in Provençal) is the crux of the Camargue’s deep-rooted taurine culture. “We have nothing but respect for them, since it is thanks to them that the course camarguaise exists,” avows Kaiss Ouennouri, Villar’s stepson and a budding raseteur. The origins of the game date back to the late 19th century. Originally called the course libre, the sport was meant to highlight the Camargue bull’s combative spirit. In makeshift arenas formed by a circle of wagons, farmworkers competed to “remove bread and sausage tied to the bulls’ horns,” explains Villar. In the early 20th century, Folco de Baroncelli created the Camargue brand that elevated the grassroots game. The mustachioed aristocratic gardian (the French version of a cowboy) was inspired by Buffalo Bill shows that he had seen during a visit to the United States. De Baroncelli recognized the need to preserve and promote the region’s hoofed heritage and piggybacked off the romanticism of the American West to convince French filmmakers to use the Camargue, aka the “Far South,” as a set for French cowboy movies. Admittedly, there were striking differences between France and America: compact bulls and waterlogged marshes instead of giant bison and arid prairies. But these Camarguais Westerns acted as an unofficial PR campaign for the region’s rich traditions. To illustrate their importance, Baroncelli designed a logo, the croix camarguaise, (the Camargue cross), composed of an anchor, heart, and trident—a tool used by ranchers to separate the bulls. He also launched the Nacioun Gardiano association to codify the course camarguaise. The sport became official in 1975 with the formation of the French Federation of the Course Camarguaise (FFCC). “Camarguaise” is somewhat misleading, for the hundred or so arenas stretch beyond the Camargue as far west as Montpellier and north to Avignon. Village arenas host events between March and November, most selling course tickets at 5 – 20 euros, depending on the competition. Weekends are often punctuated by an abrivado, a street parade of folkloric costumes and the emblematic white Camargue horses escorting the black bulls. Lined with red wood walls and shaded by plane trees, the arenas are a refreshing break from the bling of modern sports venues. The course opens with provincial pomp. To the tune of a trumpeting band and the aforementioned opera, local ladies in hoop skirts and straw hats form a pathway to welcome the raseteurs, who have dressed in all white since Baroncelli’s time. Anywhere from four to 20 raseteurs compete at a time. The slim athletes prep for the race by jogging around the perimeter and using the arena’s walls to stretch their legs. Watching them, even I felt nervous about the challenge they were about to face. “You always have a bit of fear befo

A dusty arena in the French village of Marsillargues seems like an improbable setting for Carmen. The crowd is dressed in patterned shirts and denim—Provençal rancher wear—instead of opera attire. Yet, when Bizet’s rousing song booms over the loudspeaker, the cheers aren’t for a robust tenor taking center stage, but rather a brawny black bull. This beast is the star of a centuries-old tradition in the southern region known as the Wild West of France.

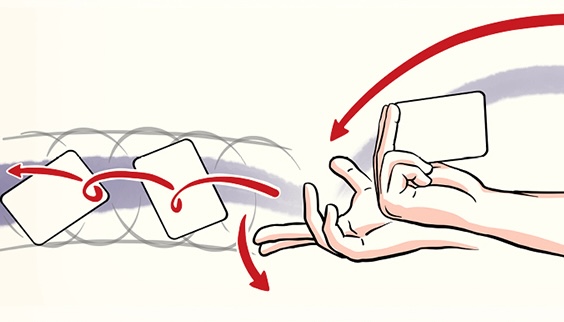

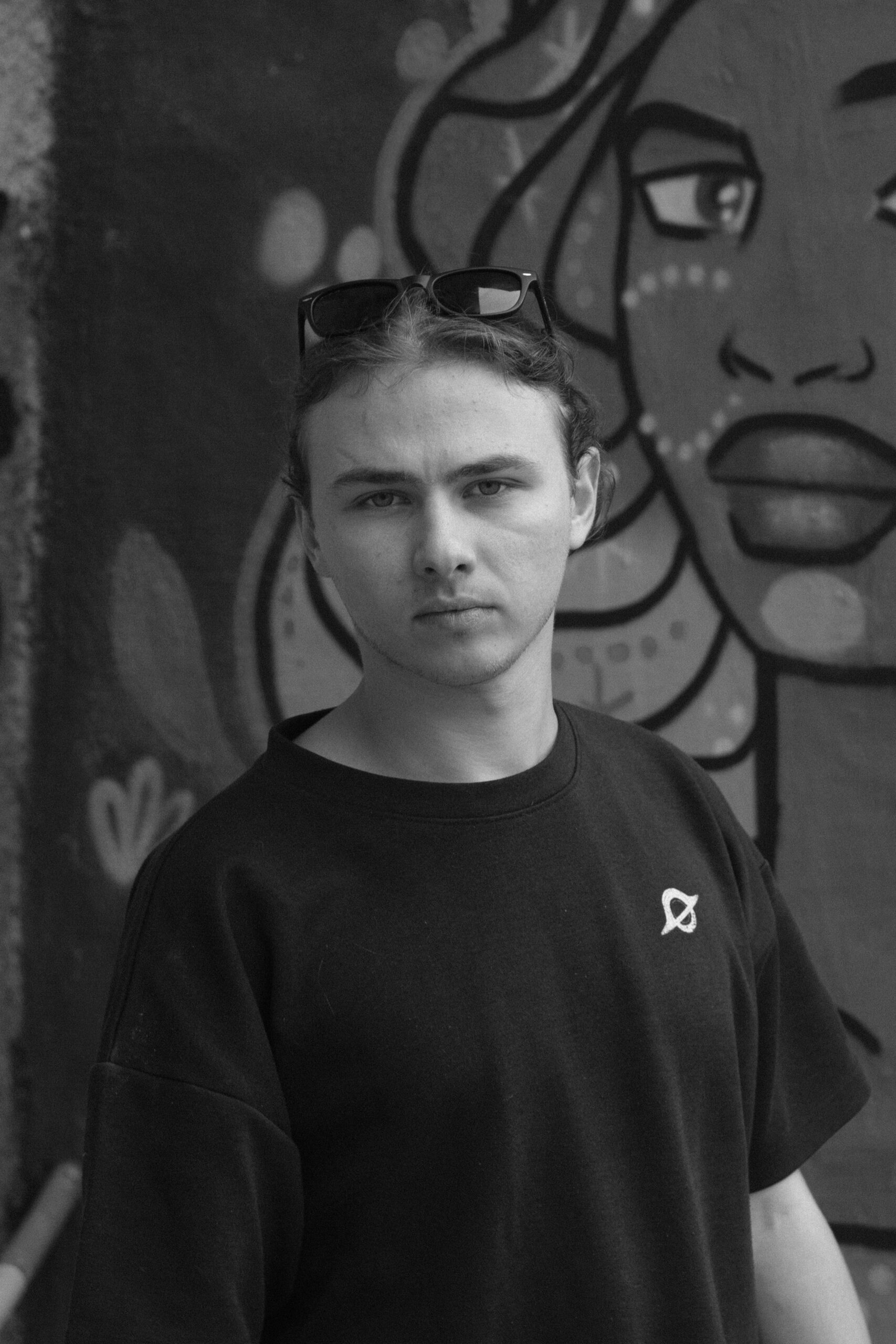

Straddling sport and spectacle, the course camarguaise is a friendly, not fatal, affair that blends small-town rodeo with Spanish corrida. Unlike bullfighting, in which man and beast engage in a dance that is destined to end in the animal’s demise, the choreography of the course camarguaise showcases the bulls' might without endangering their lives. Young men (and, on some occasions, women) dressed in white, called raseteurs, run at a bull to nab prizes affixed to his head and horns. When the bull charges, they jump out of the arena to avoid sharp horns that can pierce their skin “like a knife slicing through butter,” says Benjamin Villar, a champion raseteur who now dedicates his time to training.

The course camarguaise is named for the rugged region where it was invented: the Camargue. Whipped by gusty winds, Europe’s largest wetland sits where the Rhone River spills into the Mediterranean Sea. The Camargue’s wild mosaic of fields, marshland, and salt flats are peppered with a unique mix of pink flamingos, ivory horses, and ebony bulls. There are nearly twice as many cattle as humans in the region.

These are Camargue cattle, or Raço di Biòu, a domestic breed that is raised in semi-feral conditions in the marshes. The bulls, which can weigh over 800 pounds, are revered like kings. “The bulls get top billing on the marquee at the course camarguaise,” says Villar. Statues of bulls stand proud in towns that have arenas. The most victorious are buried standing up, their heads turned towards the sea.

In his 1994 book on bullfighting in the Camargue and Andalusia, the anthropologist Frédéric Saumade writes how locals “Have a genuine faith…and love…for the untamable biòu.” This fé de biou (“faith in the bull” in Provençal) is the crux of the Camargue’s deep-rooted taurine culture. “We have nothing but respect for them, since it is thanks to them that the course camarguaise exists,” avows Kaiss Ouennouri, Villar’s stepson and a budding raseteur.

The origins of the game date back to the late 19th century. Originally called the course libre, the sport was meant to highlight the Camargue bull’s combative spirit. In makeshift arenas formed by a circle of wagons, farmworkers competed to “remove bread and sausage tied to the bulls’ horns,” explains Villar.

In the early 20th century, Folco de Baroncelli created the Camargue brand that elevated the grassroots game. The mustachioed aristocratic gardian (the French version of a cowboy) was inspired by Buffalo Bill shows that he had seen during a visit to the United States. De Baroncelli recognized the need to preserve and promote the region’s hoofed heritage and piggybacked off the romanticism of the American West to convince French filmmakers to use the Camargue, aka the “Far South,” as a set for French cowboy movies.

Admittedly, there were striking differences between France and America: compact bulls and waterlogged marshes instead of giant bison and arid prairies. But these Camarguais Westerns acted as an unofficial PR campaign for the region’s rich traditions. To illustrate their importance, Baroncelli designed a logo, the croix camarguaise, (the Camargue cross), composed of an anchor, heart, and trident—a tool used by ranchers to separate the bulls. He also launched the Nacioun Gardiano association to codify the course camarguaise.

The sport became official in 1975 with the formation of the French Federation of the Course Camarguaise (FFCC). “Camarguaise” is somewhat misleading, for the hundred or so arenas stretch beyond the Camargue as far west as Montpellier and north to Avignon. Village arenas host events between March and November, most selling course tickets at 5 – 20 euros, depending on the competition. Weekends are often punctuated by an abrivado, a street parade of folkloric costumes and the emblematic white Camargue horses escorting the black bulls.

Lined with red wood walls and shaded by plane trees, the arenas are a refreshing break from the bling of modern sports venues. The course opens with provincial pomp. To the tune of a trumpeting band and the aforementioned opera, local ladies in hoop skirts and straw hats form a pathway to welcome the raseteurs, who have dressed in all white since Baroncelli’s time. Anywhere from four to 20 raseteurs compete at a time. The slim athletes prep for the race by jogging around the perimeter and using the arena’s walls to stretch their legs. Watching them, even I felt nervous about the challenge they were about to face. “You always have a bit of fear before it starts,” says Ouennouri.

The announcer introduces the bull basketball-player style, calling out the name of his manade (ranch) as he trots into the ring. One at a time, the men in white attempt to grab attributs (prizes) from the bull: a red fabric cocardier on the bull’s forehead, a pair of white pom poms that pay homage to the castrated bull’s former family jewels, and tightly wound ribbons wrapped around the horns. The raseteurs sport Edward Scissorhands-style tools on their hands, called crochet, to remove the ribbons—an act that requires both elegance and speed.

“The more you take risks, the more you are liked,” explains Villar, since said risks unleash the bull’s bravo (bravery). After all, that’s what spectators came to see—the crowd squeals when raseteurs leap acrobatically from the arena, hitting the wooden walls with a loud thwap as the bull grunts below. The men land so close to me that I feel like I can catch them, an intimacy that is part of what makes this sport so appealing. Traditional bullfighting pits man against beast, but in the course camarguaise, it’s more like man and animal. “You must not treat them as an adversary,” says Ouennouri, quoting the renowned raseteur Joachim Cadenas. “They are teammates that guide you.” This mindset illustrates how this version of bullfighting is kinder to animals. “The only bulls in the ring are the ones that want to be here,” Ouennori reminds me.

The camarguais breed has a grab bag of traits that suit the sport: a smaller stature that lends itself to speed, an instinct to engage with humans, and an unpredictability that adds drama. Keenly intelligent, they remember their role in the arena despite not being able to be trained to do so. “A biòu either has bravo or not,” explains rancher Thierry Félix in a thick southern twang. This bravery is what the sport is built on.

The Manade Félix ranch is in Aimargues, a pastoral town dotted with farms, vineyards, and ranches. Most of the 130-strong herd are raised for the course. Those that lack the necessary vigor, around 40 per year, are slaughtered for their meat. Beloved for its flavor and low fat content, Taureau de Camargue was the first French beef to get the appellation d'origine contrôlée (AOC) label—the same system that says a sparkling white wine can only be called Champagne if it comes from the Champagne region of France. “We were farm to table before that became trendy,” Félix says with a smile. The herd mostly lives in autonomy outdoors. Félix’s only interaction with them is to check on the bulls’ health—and round them up for races.

Away from humans, the cattle are peaceful herbivores. They only become dangerous when approached by foot, so ranchers round them up on horseback. Félix does so with his daughter, Camille, son, Vincent, two friends, and, to my surprise, me, without asking if this city slicker has ever ridden a horse. “You look like a tourist,” he teases, correcting me that real cowboys don’t clutch the saddle with their left hand—they let their arm roam free.

We trotted to the herd, forming a barrier with our horses to contain them in one part of the field. Though the cattle all looked identical to me, Felix knows each one by sight. His daughter galloped toward the bull who would compete in that day’s course. He bolted, causing the others to scatter like a flock of Camargue swallows. Thankfully, they didn’t come near me—I was so frozen in fear I couldn’t have followed Félix’s instructions to gallop to the field’s perimeter if the bulls barreled at me. Eventually the team chased the bull onto a truck to transport him to the arena.

Like Villard, Félix was a raseteur. Their sons have taken the reins, as is common in this patrimonial sport. “It’s too dangerous to start at age four like in football,” explains Ouennouri. Wannabe raseteurs get their feet wet with toro-piscine, a quirky game that involves coaxing cows into a kiddie pool. Next, they do rigorous training at academies where “the physical is as important as the mental,” according to Villard. In his 15-year career, he was one of the rare raseteurs who earned enough to live on—around 60,000 euros. Like many, his tenure ended due to the sport’s inevitable injuries.

Now president of the FFCC’s sporting commission to elevate the schools’ standards, Villard continues to champion the course camarguaise. Like him, the sport is a spokesperson for the taurine culture that lies at the heart of the region. The bulls play as much of a role in the Camargue as its human inhabitants, contributing to the economy, forging community ties, and upholding time-honored traditions. Even their grazing maintains the unruly land that is jeopardized by climate change.

Attendance levels for the course camarguaise have been steadily rising each year (more than 400,000 people watched a race in 2024) thanks to recent initiatives to bring in new spectators and tourists. And more local youth are training to be raseteurs. Their cultural diversity—the region has a large immigrant community from North Africa, of which Kaiss is part—illustrates how the sport is evolving with the times while remaining rooted in the land’s history.

![‘Vlad Circus: Curse Of Asmodeus’, Sequel to ‘Descend Into Madness’ Announced for PC, Consoles [Trailer]](https://i0.wp.com/bloody-disgusting.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/curseofasmodeus.jpg?fit=900%2C580&ssl=1)

.jpg?width=1920&height=1920&fit=bounds&quality=80&format=jpg&auto=webp#)

OSAMU-NAKAMURA.jpg?width=1920&height=1920&fit=bounds&quality=80&format=jpg&auto=webp#)

.png?#)