Teddy Swims Wants to Be the Guy You Think He Is

Teddy Swims is just back from the gym. Freshly showered in a sleeveless black T-shirt that shows off even more of his tattoos, the man born Jaten Dimsdale still has endorphins pumping when he sits down to talk with me. He’s midway through a European tour, having just wrapped up a show in Manchester, England, […]

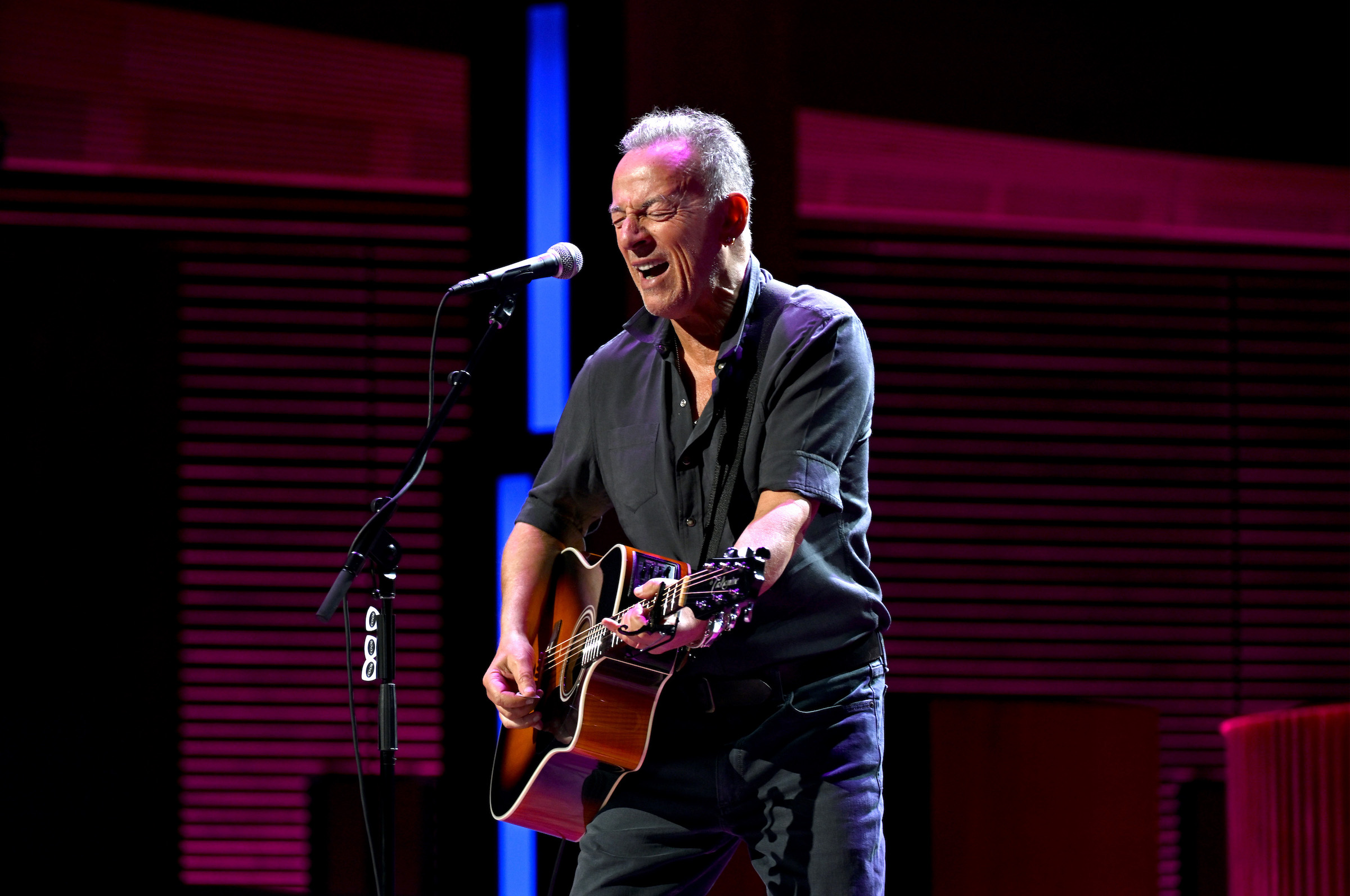

Teddy Swims is just back from the gym. Freshly showered in a sleeveless black T-shirt that shows off even more of his tattoos, the man born Jaten Dimsdale still has endorphins pumping when he sits down to talk with me. He’s midway through a European tour, having just wrapped up a show in Manchester, England, but still finds time to work out. It’s one of the many ways he stays sane on the road. “I love the U.K.,” he exclaims. Swims talks in an excited rush of words, enthusiastic and outgoing. “They’re super party people. Everybody here gets down. They just love soul music in general, soulful voices, and real singers. I’ve always gone over pretty well here, more than I do in America. We’re always waiting for America to catch up.”

The States are catching up to Swims, whose 2023 single “Lose Control” is still enjoying a truly historic run on the charts. An anthem of romantic anguish that sounds like it could have been written 50 or 60 years ago and covered countless times ever since, the song has spent more than 80 weeks in the Billboard Hot 100, with more than 50 of those weeks in the Top 10 and with one of those weeks at No. 1. In 2025, Swims was nominated for the Best New Artist Grammy in one of the most stacked lineups in recent memory, alongside Shaboozey, Sabrina Carpenter, Doechii, Benson Boone, Khruangbin, and winner Chappell Roan.

More from Spin:

- A Day in the Life of…Two-Man Giant Squid

- Every Stevie Nicks Album, Ranked

- Brand New Return For Tour After Eight-Year Break

In all the hubbub it’s easy to forget what an ambitious synthesist Swims is and what a distinctive vision he has for pop music. He emerged with a sound already in place, one that mixes old-school Southern soul, corner stoop doo-wop, country, pop, R&B, and hip-hop. His second album, I’ve Tried Everything But Therapy (Part 2), features cameos from R&B singer Giveon as well as Memphis rapper GloRilla. Swims has sung with Meghan Trainor, Tiago PZK, Mitchell Tenpenny, Orville Peck, and Illenium. His songs move with the sense that anything might happen, that he could bring any sound or tradition into his music.

He comes by it naturally. Swims was born and raised in Conyers, Georgia, a small town caught between the hip-hop scene in Atlanta, the underground rock scene in Athens, and the immense R&B legacy of Macon. He absorbed all of those styles and more as a teenager just discovering his voice, and his first performances were in high school productions of Rent and Joseph & the Amazing Technicolor Dreamcoat. To fine-tune his instrument, he went down YouTube rabbit holes, watching endless videos of his favorite artists and carefully studying their techniques. He performed in a variety of bands around Atlanta before landing a slot opening for Tyler Carter on a national tour. He released two EPs in the early 2020s, but still hit the charts like an overnight sensation.

Released in 2023, Swims’ debut full-length, I’ve Tried Everything But Therapy (Part 1), put his large musical vocabulary to work on songs that documented a painful breakup and a period of intense darkness. From that trauma came “Lose Control,” which treats love like addiction (“It’s takin’ a toll on me, trying my best to keep from tearin’ the skin off my bones”), but also fan favorite “The Door” (“I saved my life when I showed you the door”). Part 2, released in January, is a brighter, more hopeful installment, one that celebrates a new and stabilizing romance with the singer Raiche Wright. There are still moments of despair, but they never quite feel as insurmountable as they did on Part 1.

Swims has emerged as part of a new wave of male singers like Jelly Roll (“I Am Not Okay”), who’ve made their mental and emotional health a big part of their music. And yet, he seems to be handling the pressures and demands of sudden success pretty well, especially for someone who has titled two albums I’ve Tried Everything But Therapy. In fact, he has even tried therapy. “There have been times when I couldn’t keep my lights on, and now there are different pressures with this job,” he says. “Now there are different physical and emotional tolls. But mentally, I’m in such a better place, having therapy and good people around me and a safe place where I can walk out every night and talk about my feelings.”

Growing up in Conyers, how aware were you of all the music history around you?

I knew it was sort of a melting pot for music. I was so lucky to grow up with some of the best hip-hop ever, some of the best country ever, some of the best R&B ever, all around me. We had André 3000 and Big Boi, T.I., Ludacris. We had Gucci Mane, and Ray Charles, James Brown, Otis Redding. The list goes on and on. My home state was such a beautiful place, and I was able to be exposed to it all. It was everywhere. You flip on a station and you could always hear something coming out of Georgia.

Did you get to see any of those artists?

Not really. I got to see Big Boi one time, but this was before Outkast had kind of gotten back together, so I never got to see the both of them. But Aquemini and ATLiens are two of my favorite albums ever. They both sound so ahead of their time. The last time we got to play in Macon a couple of years ago, I got a chance to meet Otis Redding’s daughter Karla, who gave me a bunch of old merchandise and memorabilia. There’s an after-school program there where kids can discover music and learn guitar and learn how to produce. It’s cool that Otis’ legacy is still a part of that kind of stuff, too. He’s my favorite singer ever, and I would love to have met the man. But meeting his daughter was amazing. It was a bucket-list moment just to get to know her.

I feel like I can hear a bit of him in your vocals, in that you’re holding back in an artful way. That hits a little harder.

Vocally, he’s my person. I’ve tried to use my voice to replicate the way he sings. You can do all the acrobatics and all the runs and stuff, but that can take away from the emotion of it. And the emotion is the most important thing! If you’re taking away from the melody and what the song means, then you’re hurting the song. I think Otis was the best person in the world to know how to hold a note and give it volume and crescendo and vibrato. But he also knew when to hang back. He would always do those big yells into something little, like on “Mr. Pitiful.” He would shout and then fall off. [Swims demonstrates this technique perfectly.] When I first started singing, I was like, How do I get that? How do I convey that kind of tenderness with a yell? He could go straight from urgency to tenderness. I fell in love with him for that.

Is it difficult to get into that headspace every night?

It can be, but singing is as much acting as it is singing. You have to really get into that emotion, even when you’ve already healed yourself from the thing you’re singing about. It could be that girl who broke your heart so many years ago, but for three minutes I have to give myself fully to that emotion in order to really sing the song from the right place. What’s beautiful about it, though, is that once you do tap into it, as soon as the song’s over, you can tap back out of it. You can remember where you came from and even celebrate that heartbreak when you’re on the other side of it. You can see how far you’ve come and how much that’s made you who you are now. Sometimes that’s a good reminder to let yourself feel those things that deeply again, even if it’s just so you don’t do it again.

So it offers perspective on these previous stations in life?

Exactly. Sometimes it’s great to lean back in. That’s one thing I’ve really been learning about, especially writing songs right now. It’s easy to write a love song when you’re in love, but it’s harder to write that heartbreak song when you’re in love. If I do have that feeling in my heart or if I do want to say something about this particular topic, it’s nice to know that I can tap back into those emotions and give myself over to them without feeling like I have to live in that emotion to create that art. I don’t have to surround myself with turmoil in order to write about turmoil. Thanks to therapy, I no longer feel like I have to constantly put myself in harm’s way in order to make good art. I did these masochistic things and chose these patterns for myself, but I’m really learning how to access those emotions without letting them take me over all the time.

That seems like a much healthier way to live than to think you always have to suffer for your art.

Yes. It’s not necessary. Sometimes there is some beauty that comes out of suffering, but it’s obviously not sustainable.

Living with these songs that document these different periods in your life, do you find that they change over time or offer new meanings or implications?

I think so. What’s so beautiful now is that I can take some of those songs, like “Lose Control” or “The Door,” and I can see that I was in a dark place but just didn’t realize how dark. Now when I sing those songs, there are all these people singing along with me, thousands of people out there singing along. Now that I’m on the other side of heartbreak, now that there’s love and success and family and so many beautiful new things in my life, I can see how these songs are celebrating that heartbreak. Everybody has had something bad happen in their lives. We’ve all had some trauma, so now we put it into a song that we can sing together. At the end of the night everybody is screaming and dancing and we’re all having the best time, and we’re taking ownership of that trauma. We’re reclaiming ownership of our lives. It’s been the coolest thing to see how these songs have taken on their own life and have transformed into something like a celebration.

It sounds like you’re open to letting people interpret these songs however they need, rather than insisting it’s about this experience and this feeling.

Everybody has their own relationships and their own circumstances that they bring to the songs. It’s the same for me. I’ll use this as an example: Tha Carter III is one of my favorite albums of all time. I was just coming out of ninth grade. I was 15 years old and going to my first parties with high schoolers. I was smoking weed a lot for the first time and experiencing my own little teenage life. That whole summer I listened to Tha Carter, and it’s really a big part of my memories from that summer. I know Wayne was going through his own thing when he was making that album, but when I hear the album, all I can hear is that summer, which was the most fun, the most eye-opening, the most beautiful story in my life. There’s nothing in the music about a 15-year-old kid coming of age, but it still brings me back to that time. And that’s truly the function of music, isn’t it? Everybody can take it and find their own meaning in it. That’s wonderful. I can still have my own connections to it, and it can still mean different things to different people. It’s almost like scripture in a way.

People have obviously made their own connections with your two I’ve Tried Everything But Therapy albums. Do you see it as a continuing series, or do you think you’ll stop at two?

I didn’t want to leave it at just one entry, because Part 1 was nothing but turmoil and heartbreak. As I’ve actually tried therapy and fallen back in love and now I’ve got a kid on the way, I wanted Part 2 to come from this healed place and reflect this part of my journey. On the other side of all that heartbreak, I found so much love and family and support and success and so many good things. I wanted to say, Don’t let this kill you. Don’t let this ruin you. Stay on the path and it’ll get better. When I listen to these two albums, I can hear how much I’ve grown, and I hope the listener gets the same feeling. That’s what I wanted to communicate from the first record to the second.

There are so many stories about artists who find success but it only complicates their lives. It sounds like it might be going the other way for you.

Many of these things have gotten more complicated along the way, but my fans have made such a safe place for me to express where I am emotionally, and that keeps me in a good place. There are bad days, but I know I can get on that stage and say, I’m having a terrible day, guys. That alone will turn things right around for me. Hopefully I can turn around and create a safe place for them, at least for two hours in the evening. It helps that I don’t have to put on a façade. That’s where a lot of artists get messed up. Once they get to a certain level, they think there’s gotta be a difference between them and the persona they’re carrying with their artistry.

Do you have to have boundaries? Is there a sense of oversharing or being too unguarded?

There are always some things that are going to be private. I’m not going to put my child everywhere on the internet, and there are some things about my home life that will always be private. But I still want to always be emotionally available and as transparent as possible. I don’t want there to be a Teddy Swims and then there’s Jaten Dimsdale at home. They’re not two different people. I want to be the same person on and off the stage. When I step up to the microphone to sing a song, I want to be the same person that you might see on the street. I want to be the guy you think I am.

To see our running list of the top 100 greatest rock stars of all time, click here.

![“Tokyo Ghoul” and Ken Kaneki Now Available in ‘Dead by Daylight’ [Trailer]](https://bloody-disgusting.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/dbdtokyo.jpg)

![Extended: Buy Marriott Bonvoy Points with a 45% Bonus [0.86¢ or ₹0.74/Point]](https://boardingarea.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/46523d48a9dbea5cac3a9961201c257d.jpg?#)

![Miles & More Mileage Bargains Promo Awards [Apr’25]](https://boardingarea.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/335d951d4569e7d51813bc1c8be3a5d1.jpg?#)

.png?#)

.jpg?width=1920&height=1920&fit=bounds&quality=80&format=jpg&auto=webp#)