Pretend it’s a video game: How films emulate gaming mechanics

As a (very loose) adaptation of Until Dawn hits cinemas, it's worth investigating the successful – and unsuccessful – attempts to explore what it feels like to play a video game on the big screen. The post Pretend it’s a video game: How films emulate gaming mechanics appeared first on Little White Lies.

David F. Sandberg’s new horror film Until Dawn is based on the 2015 video game of the same name, which has caused some confusion or even consternation among fans of the source material, since the film seems to have little overlap with it. In the game, players control eight different teens at a snowy mountain ski lodge who are menaced first by a masked killer and then by a pack of wendigos. The movie follows a completely different group of young people who find themselves trapped in a time loop wherein each iteration sees them up against a different horror scenario – a murderous clown, a looming giant, face-rotting parasites, etcetera. Besides a few details, like a missing sibling as a plot device or the use of actor Peter Stormare, Until Dawn the movie bears little resemblance to ‘Until Dawn’ the game. Sandberg has said that the movie “expands upon the universe” of the source material in lieu of reusing its plot, explaining “the game is pretty much a 10-hour movie, so I think it wouldn’t have been as interesting for me if we were doing just the game, because then it’s going to be like a cut-down, non-interactive version of the game, which just wouldn’t be the same thing.”

The filmmaker’s comments speak to a perpetual issue in adapting video games for film. A large part of the appeal of gaming is participating in the action yourself; strip away the interactive aspect, and going through the same story beats can feel tedious. This dilemma has become more pertinent as games have been increasingly used as the basis for blockbusters in recent years. Before that trend was solidified by box office successes like A Minecraft Movie, Sonic the Hedgehog, Five Nights at Freddy’s, and The Super Mario Bros. Movie, turning games into films was long a fraught enterprise. It’s a history littered with flops ranging from 1993’s Super Mario Bros. to Assassin’s Creed to most of Uwe Boll’s oeuvre – all films which, to varying degrees, were greeted with critical and fan responses along the lines of “Why even bother?” However, there are scattered films that have meaningfully captured some part of the gaming experience. They aren’t always the titles one would expect, and surveying them helps clarify what makes cinema and gaming distinct as art forms.

The 2022 film Uncharted is a great case study for the failures of just transposing the plot of a game to a film. It replicates a major action sequence from ‘Drake’s Deception’, the third game in the series it’s based on, in which protagonist Nathan Drake clings for dear life to crates strung behind a plane thousands of feet up in the air. This is thrilling to play but a chore to watch. A live-action Tom Holland poorly composited into a wholly computer-generated vista means the scene lacks any sense of weight or gravity. Things animation can convey easily become unconvincing in another medium. Sticking with the theme of adventuring archaeologists, the various attempts at Tomb Raider films also illustrate this obstacle. If you remove player input, it’s difficult for the concept to not come across as little more than a distaff Indiana Jones rip-off.

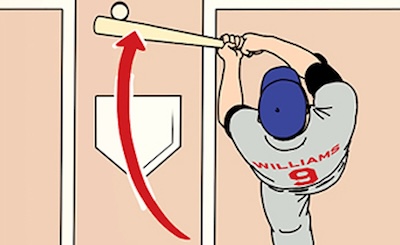

Some game adaptations decided to rectify this experiential gap by trying to replicate some key aspect of the source. The ‘Max Payne’ action games are notable for their slow-motion “bullet time” mechanic, which turns what could be chaotic shoot-outs into more measured problem-solving situations. The 2008 film also occasionally uses the effect, but when you’re merely seeing Max Payne shoot guys in slo-mo rather than taking advantage of it yourself, you wonder why you aren’t watching a Matrix movie instead. ‘Doom’ is a landmark game for the ways it pioneered the conventions of the first-person shooter; the 2005 movie adopts a first-person perspective for one action scene, an extremely “This is what you kids like, right?” move that misses the whole point of why games use that POV. In a ‘Doom’ game, you are the Doomguy, and the camera represents your gaze. The viewer is not Karl Urban, and briefly seeing things through his eyes is disorienting rather than producing any sense of identification. Roger Ebert (characteristically dismissing gaming as a medium in passing) described it as “like some kid came over and is using your computer and won’t let you play.”

However, there have been films that have utilized the first-person POV in a way that resonates with how it works in games – notably not game adaptations. In the nightmarish opening to John Hyams’ Universal Soldier: Day of Reckoning, we see the protagonist’s family murdered before his eyes through his eyes, which kicks off a story that’s distinctly gamey in the way it progresses from one combat encounter to the next. But then, in a twist, it turns out that first scene was a false memory used by sinister forces to motivate the lead to go on his rampage of revenge. It’s a dark deconstruction of the simplistic vengeance-minded tropes that drive action stories in both games and film.

A similar twist is sprung in Hardcore Henry, a film shot entirely in first person that owes a ton of its visual language to games. This is especially noticeable in its use of gestures. The titular Henry holds objects like guns or a detonator so that they’re legible for the camera, rather than in ways a human would naturally position themself. One character, Jimmy, has been cloned multiple times, and his clones tend to act like game NPCs, especially during action scenes, when they speak in quick soundbites (“barks” in developer lingo) rather than like people holding conversations, sometimes to direct Henry to where he should go and what he should do. Since the Jimmy clones are remotely controlled by the original Jimmy, there’s a humorous metatext here; the Jimmies are an army of identical non-persons controlled by an exterior intelligence to help the protagonist, much like how NPCs in a game have their scripts and exist in the service of the player’s narrative. And like the lead of Day of Reckoning, Henry is motivated by false memories (this time of a wife in peril rather than a dead one) implanted by nefarious powers to get him to do what they want. Setting aside the frequent headaches the first-person action may induce and any gimmickiness in its conception, the conceit genuinely works to put the audience in the position of a person who’s essentially a blank slate.

The many deaths of Jimmy in Hardcore Henry recall a subplot in Resident Evil: Extinction. Series lead Alice has also been cloned, and the evil Umbrella Corporation has been subjecting one copy of her after another to violent experiments, enough times that there’s a ditch full of dead Alices. The setup posits a morbid spin on the familiar game scenario of one character who goes through multiple deaths in their effort to make it through a level – what if instead of being reborn each time, every playthrough was an individual person who’s been killed off? At the end of the film, Alice frees her clones and forms them into an army to get payback on Umbrella – an assault seen in the opening of the next Resident Evil film, Afterlife. The player character and all her extra lives have teamed up, broken out of this dark version of reincarnation, and are pissed off at the game developers for forcing this existence on them. The fifth installment in the series, Retribution, takes the metatext even further, with the heroes trying to survive a series of VR simulations that distinctly feel like different gaming worlds – a recurring visual motif has an Umbrella villain monitoring them through security camera footage arranged in grids that look an awful lot like a level select screen.

Paul W.S. Anderson directed and/or wrote all three of those Resident Evil movies, and his later game adaptation Monster Hunter also feels in direct conversation not just with the storyline of its source material but also the experience of playing it. A good portion of the film is simply Milla Jovovich’s character wandering an alien landscape, learning about it and its hostile fauna, in a way that’s strongly redolent of what it’s like to explore an open world in a sandbox game.

An even better approximation of the exploration game vibe came with the recent cult hit Hundreds of Beavers. Though the film is not based on a game, director Mike Cheslik has acknowledged how, along with silent cinema and classic cartoons, gaming was a direct influence on it. The plot is structured around a collectathon-style quest for beaver pelts, and the audience is constantly shown a map marked with the lead’s current location and all the points of interest he’s found. More pertinently, his repeated series of fuckups, each of which teaches him in a slapstick way how the wilderness works (this cave is full of wolves, this rope trap will fling him to this specific part of the forest, etc.), exemplifies a player’s progression through a learning curve. Cheslik has even likened the movie to being a Let’s Play for a game that doesn’t exist.

A few other titles also convey the vibe of the knowledge-gathering parts of gaming. One of the less-discussed influences on the TV series Lost was the classic point-and-click puzzle game ‘Myst’. As showrunner Damon Lindelof put it in an interview with Time: “What made [‘Myst’] so compelling was also what made it so challenging. No one told you what the rules were. You just had to walk around and explore these environments and gradually a story was told. And Lost is the same way.” The podcast ‘The Lost Broadcasts’ has explored this connection further. Co-host Esther Rosenfield likens Lost to a game where “there is no directed quest.” (Which was a frequent source of frustration for viewers hungry for more answers to the show’s many mysteries.)

But few works capture what it’s like to stumble through a game where you don’t understand the rules or what’s going on better than the 2019 disasterpiece Serenity. This is appropriate, since the plot’s climactic reveal is that Matthew McConaughey’s whole world is a homebrewed virtual environment, and that all along he’s being controlled by a teenage boy. Said boy based McConaughey on his deceased father, and he crafted this game to steel his nerve to kill his abusive stepfather. Once again, a game-like film features someone who awakens to and grapples with their lack of agency – you can call the subgenre “sympathy for the player character”. Serenity’s bizarre character beats, thematic incoherence, and constant weird-out moments (a pre-Succession Jeremy Strong walks into and then out of the sea with the unflappable stoicism of a Terminator) make it feel uncannily like a buggy indie game that’s a labor of love from one questionably talented programmer.

On the opposite end of the spectrum is the ultra-polished, high-budget sci-fi action flick Edge of Tomorrow, in which Tom Cruise’s public affairs officer Major William Cage becomes stuck in a time loop on the day of a major battle against an alien army. Through dying repeatedly and gaining a little bit more experience with each go-around, he progresses from a hapless, cowardly adjunct to a hypercompetent warrior. Experiential loops are integral to the game experience, so in a way, every film about a time loop contains some essence of gaming. But Edge of Tomorrow stands out for how Cage specifically uses the loop to hone his skills, how the narrative function of his situation is not to impart self-knowledge like in Groundhog Day, but to provide him with an endless training simulator. It’s not just that he gets better at using his powered exoskeleton, either; the way Cage learns precisely how everyone around him will act, and consequently how their behavior changes if he intervenes in different ways, demonstrates perfectly how a player internalizes enemies’ programmed attack patterns and NPC scripting trees.

The time loop idea brings us back around (appropriately) to the film of Until Dawn. It’s interesting that the writers thought that incorporating the concept would help the movie hew closer to the game despite the new plot. ‘Until Dawn’ is one of the few games without a death-and-do-over mechanic – you instead are meant to roll with every story development, even unanticipated character deaths. Still, Sandberg cites the ability to replay the game as the inspiration for the time loop conceit. Much of what the writers have said about the film in interviews about how they’re paying proper tribute to the game through Easter eggs and other homages seems to dance around one problem: ‘Until Dawn’has a purposefully basic story, even bringing in horror scribe Larry Fessenden to assist with the script. The fun of the game comes from how you can shake things up and change what happens within this framework. Without that, straightforwardly recreating the plot would likely feel pointless. A time loop, though, is something that feels “game-like” enough to justify the tie to this particular intellectual property. But as is clear from decades of trial and error, there are so many other ways to crystallize the spirit of gaming in cinema.

The post Pretend it’s a video game: How films emulate gaming mechanics appeared first on Little White Lies.

![Stephen King Reads an Excerpt from New Novel ‘Never Flinch’ [Video]](https://bloody-disgusting.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/stephenking-reading.jpg)

![How George A. Romero’s ‘The Amusement Park’ Went from Lost Media to a Graphic Novel [Interview]](https://i0.wp.com/bloody-disgusting.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/Cross.jpg?fit=1200%2C904&ssl=1)

![How Havoc Director Gareth Evans Created The Movie's Biggest, Wildest Action Setpieces [Exclusive Interview]](https://www.slashfilm.com/img/gallery/havoc-interview/l-intro-1744994568.jpg?#)

![Quentin Tarantino Talks The Screenplay He Wrote For Action Filmmaker John Woo That Never Materialized [Rewind]](https://cdn.theplaylist.net/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/25071942/Quentin-Tarantino-Talks-Screenplay-He-Wrote-For-John-Woo-That-Never-Happened-Rewind.jpg)

![Earn 5,000 Bonus Points for Paying Bills with Hyatt Card [Targeted]](https://boardingarea.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/f8cad0855e8ffab71e3c8ad284d8004b.jpg?#)

![Hotel Beds Outperform Your Master Bedroom for Better Sex—Here’s Why [Roundup]](https://viewfromthewing.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/burj-al-arab-bed.jpg?#)

.jpg?width=1920&height=1920&fit=bounds&quality=70&format=jpg&auto=webp#)

![[Podcast] Unlocking Innovation: How Play & Creativity Drive Success with Melissa Dinwiddie](https://justcreative.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/melissa-dinwiddie-youtube.png)