That’s What Disruption Does For Me: Gareth Evans on “Havoc”

The action director takes us blow-by-blow through his latest melee for Netflix.

One throughline of Welsh director Gareth Evans’ films is their punishing bleakness. Best known for the Indonesian crime martial arts films like “The Raid” and its sequel, Evans’ films linger on moments where many would turn their lens elsewhere. Take a moment in “Apostle” where we see a youth get publicly executed by having a drill burrowed deep into his skull; we feel every time the metal twists pierces bone. Despite the brutality, Evans has continually found ways to make vicious music out of his characters’ bellicose tendencies, staging the action and violence his characters inflict on each other’s bodies with an artistry that feels noble rather than pernicious. There isn’t anything quite as barbarous as the drill kill in Evan’s latest action film “Havoc,” but that sense of lyricism and cruelty remains.

Evans has a knack for spotting action chops in someone and giving them a platform to display their talents, from Sope Dirisu in “Gangs of London” to Iko Uwais, who has appeared in three of Evans’ films. It’s exciting to see his muscular filmmaking paired with a veteran like Hardy, a martial artist himself who has deployed a range of fighting skills across various projects, from George Miller’s “Mad Max: Fury Road” to Christopher Nolan’s rendition of Gotham City.

Shot in Cardiff, where Evans also shot “Apostle” and “Gangs of London,” “Havoc” takes place in an unnamed American city where a grizzled Hardy stars as Walker, a detective who’s just trying to get his daughter a Christmas present. As films of this sort go, the night will be anything but straightforward: Walker is conscripted by the city’s corrupt mayor, Lawrence Beaumont (Forest Whitaker), who wants Walker to save his son, Charlie (Justin Cornwell). Charlie’s involvement in a drug deal gone wrong sees no less than two warring factions out to kill him and his friends: a crime syndicate and a group of corrupt cops. With only Ellie (Jessie Mei Li), another officer, as his backup, Walker has to defend Charlie from a horde of killers who are more prone to shoot (or stab, bludgeon, etc.) first and ask questions later.

There are two standout action sequences in the film, one taking place at a nightclub and the other at a fishing shack, and for Evans, the way he shoots those fights is just as important as the choreography itself. “I’ve become more obsessed with making sure that the camera angle is the right angle to tell that piece of action,” he shared.

Evans spoke with RogerEbert.com about how the film changed from when he first began working on it four years ago, the significance of nightclubs in action movies, and creating moments of levity in an otherwise thematically harrowing film.

This conversation has been edited and condensed for clarity.

Could you elaborate on the project’s delays and how they have evolved from when you first conceived it to the current version audiences see?

I wanted this film to be a love letter to the Hong Kong heroic bloodshed genre films I grew up watching in the eighties and nineties. Specifically, I wanted to pay homage to the films of John Woo, Johnnie To, and Ringo Lam. From that seed of an idea, I followed our usual process: I did the previsualization work, and then Tom joined the project, and we further developed the character together.

We had a surprisingly smooth production, despite being amid the COVID pandemic. That’s a huge credit to the crew and cast, but also to our incredible COVID team for keeping us all safe and secure during the shoot. During post-production, we came up with a cut we were satisfied wit,h but there were some points we wanted to address, like some backstory elements Walker wanted to bring into the former.

We hit a stumbling block because we had such a wide ensemble cast, but especially once things started opening up again, it was boom town in the industry, so everyone got jobs. So lining everybody up for the same week or two weeks’ worth of filming proved almost impossible. Then we were hit with the WGA and SAG strike,s which delayed us further. It took almost three years for us to find a two-week slot that would bring everyone in the room together. It was the weirdest thing because, in a way, I had two and a half years where I just felt I was in standby mode. I’m waiting to finish the movie and was excited to share it. I think those delays gave me the luxury of distance, allowing me to go back into the edit and refine some elements of the story, and be more laser-focused during the two weeks of shooting pickups.

That makes me think of how “The Raid 2: Berandal” was originally set in a school before working on the first film impacted the development of the sequel. Can you talk more about the role of disruption in your creative process?

That’s fascinating … I’ve never really thought about that as a concept. You know what it is? It’s about keeping your eyes open and listening—that’s what disruption does for me. With the development of “Havoc,” it began as my desire to create a ninety-five-minute thrilling action film that serves as a love letter to the genre. I was pretty committed to a particular vision I had for that, but then when I landed someone like Tom Hardy, it opened up a world of possibilities. I know he can deliver on the action side of things. Still, I can now imbue them with an undercurrent of emotionality and the complexity of a lead character that perhaps wasn’t necessarily on the page to begin with.

So, working with him, we got to develop that character further and delve deeper into what makes him tick. Once he boarded and those delays on the project occurred, I was able to devote more thought to Walker’s emotional journey and make it a more prominent feature in the film.

It was interesting to hear that when you were crafting Hardy’s character, you went down this Spotify rabbit hole where you played a song that felt right for Walker and then would use algorithmic suggestions to make a playlist that summed up who he was tonally. What songs made it on the playlist, and is that often your approach to building characters?

A lot of those tracks wouldn’t necessarily be songs I would use in the film, but it would be music that would create a tone, vibe, or give me a sense of pace for a scene. For that opening truck chase, I was listening to this M.I.A track that I loved–I can’t remember because you’ve put me on the spot (laughs). We didn’t end up using that track in the film, but it was a huge influence on me in terms of pace and rhythm. There would be other songs that might seem like unusual choices for a film like this. I’d be listening to some Sigur Rós. There’s something beautifully emotional in all the vocal performances from that band. It added to the haunting quality that I wanted in the film. All these songs are usually an emotional leaping-off point for an emotion that I want to explore in a scene.

It was fun to hear Gesaffelstein’s “Opr.” I know a lot of people may associate that song with the “Thunderbolts*” trailer, but for me, it will always be the soundtrack to Tom Hardy’s nightclub killing spree.

(Laughs) Oh, that’s great! Thank you for that. It’s interesting with Gesaffelstein because I’ve been a massive fan since I first heard “Pursuit.” That was the first track I wanted in the film. For the nightclub sequence, I thought that it would be a fun track to kickstart the arrival of the triads. I hadn’t anticipated using four to five Gesaffelstein tracks in a row. So, if you’re listening closely, you might think that the Medusa Night Club has an interesting playlist or was on a Gesaffelstein kick if you break it down.

Yeah, if people were Shazaming songs in the club, they might notice something’s up. Nightclubs are a significant part of action cinema, and also in your work. That sequence in Medusa felt like a fun callback in some respects to your work in “Merantau.” Can you talk about the significance of nightclubs in action cinema? I’m curious what those spaces hold for you when it comes to staging your fights.

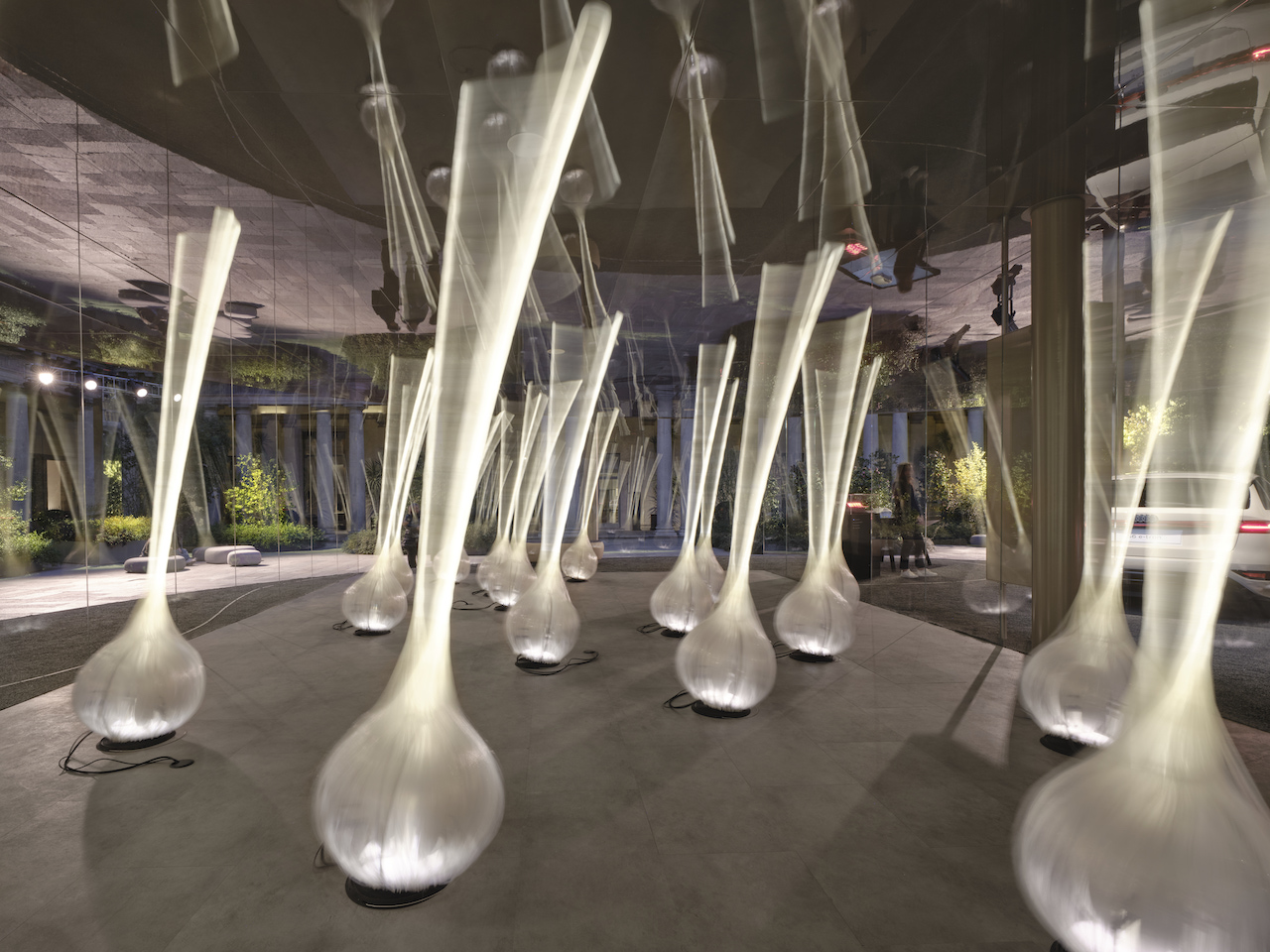

On a purely superficial level, nightclubs are always fascinating in terms of tone, mood, and atmosphere. There’s something about all those moving lights, the fact that you can locate dark places and shadows in a brightly lit space, that you can wash your characters with light, which makes them stand out in a new way. My DP, Matt Flannery, went to town on the lighting setup in the club. The art department built that whole club from scratch. It was in a sound stage with two-tiered levels. A considerable amount of construction and engineering went into making that set and the team worked hard to give it that noir-ish vibe and gritty texture.

I wanted to explore what happens when a fight breaks out in a public space, especially considering the large number of people present at a club like Medusa. It’s fascinating to see the reactions of people. There’s a sobering effect, where it now becomes everyone’s problem. The fight isn’t taking place in a quiet part of town where nobody knows about what’s going on. Taking place in a space like this means that there will be a police response. Then you throw in the triads, and the stakes start to rise on a subconscious level. No one’s going to get away clean, and there are going to be more obstacles that emerge. It’s fun to balance those cascading elements. A big influence, though, is “Collateral,” which has one of my favorite nightclub scenes of all time. That is all about mood, tension, and light coming together as one.

When working on “Apostle,” you shared how action films and horror films are similar because there’s a build-up of tension, followed by a catharsis of release. Those similarities stand out even more when you situate your fight sequence in the club, where the music is all about crescendoing before a beat drops.

Yes, we were reviewing those sequences to identify interesting moments to transition to the next song in the queue, almost as if the club music was in sync with the sequence that was playing. Our music editors would try to find ways to take the source music and then subtly adjust it so that it felt like it was designed specifically for the choreography as well.

One-takes are all the rage now, and particularly with action films, what seems to galvanize fans are elaborate one-take fight scenes or the ballet-esque choreography of something like “John Wick.” You don’t employ those elements in this film, but what strikes me is that the success of how you stage action comes down to how purposeful your editing is and the way you cut just where you need to.

Thank you. As a film fan first, I love and feed off of action cinema around the world. What Chad Stahelski and David Leitch are doing inspires me greatly. Kensuke Sonomura, who did the “Baby Assassins” fights, and Kenji Tanigaki were also inspired. When I watch those films, they have great concepts and amazing action, but what I don’t want to do is ape them. I might have done something similar in the past, like with “The Raid 2,” where we had the prison riot sequence shot on one take.

But now with “Havoc,” with all the moving parts and the gunplay we have, I’ve become more obsessed with making sure that the camera angle is the right angle to tell that piece of action. When I’m designing the action, I don’t want to be hamstrung by needing to maintain a oner because I’ll find that there are moments in a sequence where that form of shooting won’t be the best position for the camera to capture the action. The risk with the oner is that the choreography gets sloppy because mistakes happen and people get fatigued. For me, I prefer to work on these in more bite-sized pieces. I like shooting jigsaw pieces in accordance with the pre-visualization work that I’ve laid out. I want to honor that pre-viz work because my team and I have spent time scrutinizing not just the camera angles and editing points but the action itself.

Take the fishing shack fight, for example. In that sequence, we’re tracking where every dead triad member has fallen and what weapon they brought with them so that when our protagonists run out of ammo from their guns, they can discard and grab a fresh one off a dead body. They’re only grabbing weapons that have fallen within their space. We’re obviously stretching the capacity of a round and a gun (laughs).

It’s perhaps a bit more explicit for something like the Apostle. Still, I’ve been fascinated by your exploration of ritual, code of honor, ceremony, and the cults of violence that form around extreme ideologies. We see that more explicitly with the Triads here, but you can say the police force Walker is a part of is similar.

That’s an interesting connection. It’s fascinating because with “Apostle,” I never intended it to be sort of a critique of religion, because despite my personal views, which are kind of leaning more towards the atheist and/or agnostic vibe, I don’t ever want people to deny their beliefs or faith. I wanted to use the setting of a religious community to comment on the weaknesses of men in standing up to those with power and how absolute power corrupts even the most idealistic of us. In “Apostle,” people were too weak to command respect physically, so they used religion as a crutch to force people to fall in line. That’s different from “Havoc” because I envisioned it as more of a hard-boiled noir film, whose various characters have shades of grey; they all feel the pull of the power that influence can buy and have to deal with that temptation in their own ways. The only exception is Ellie, who seems like the one beacon of light we can rely upon as an audience to guide us through.

We’ve been dissecting the film’s action, but let’s return to what you were saying earlier. I was struck by this quiet moment between Forest Whitaker’s character and the triad leader, played by Yeo Yann Yann. Their discussion, in which they discussed the ways they may have negatively impacted their children, felt like a subversive moment of peace, where two leaders on opposite sides of the law were appealing to a shared humanity.

Thank you for commenting on that scene. That was one of the scenes that stuck with me emotionally while making the film. It’s this breathing space moment where two characters get to open up to each other and don’t have to play the Alpha card in front of their subordinates. They’re just two people being brutally honest about their insecurities.

In my own life, I’ve been blessed to have had a wonderful father and a fantastic mother. Although I don’t have personal experience of estrangement as a parent myself, I do have anxieties about raising my children. I was thinking through this classic scenario of when I wake up in the morning, if the first thing I do is check my phone instead of asking my children how their day is going. I think most parents start worrying and are anxious about how they may be affecting and shaping their children’s emotions and development. I carry that with me, and those small facets would inform the writing of “Havoc.” I always try to find something that I can personally relate to and then exaggerate it, making it more operatic and larger in theme, within the film itself. If there’s a kernel of truth in something I can latch onto and understand in the film, it allows me to hypothesize alongside my characters: If my child were the one caught up in a drug deal gone wrong, how would I react? How would I feel?

The film is bleak and thematically resonant as you’ve just outlined, but you use a lot of visual humor to offset some of that. I like how the harpoon gun in the fishing shack is a bit of a Chekov’s gun, or the fact that the triad members seemed determined to want to shoot out all the windows in the shack, even if it wasn’t necessary to do so. Could you elaborate on the role of humor in the film?

It was important to find levity where I could without it feeling tonally out of place. A large part of that came from the fact that Walker is someone who treads the fine line of trauma and despair. At the same time, he’s acerbic, witty, charismatic, and quite charming, and it’s his sarcasm that provides pockets of humor. In his interrogation scene with Luis Guzmán, on the page, that could play very seriously if you just took the words without the performance and just looked at what was being said. But Tom and Luis’s back and forth was so infectious, and there were days I had to put my monitor far away from the set because I just kept laughing watching these takes go by. The ad-libs and improv from both actors elevated that scene … I think of that moment of physical humor where Tom puts Luis’ phone in front of his face to unlock it. It’s such a subtle, abrupt, and brilliant interruption of the flow of conversation.

.jpg?width=1920&height=1920&fit=bounds&quality=70&format=jpg&auto=webp#)

![[Podcast] Unlocking Innovation: How Play & Creativity Drive Success with Melissa Dinwiddie](https://justcreative.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/melissa-dinwiddie-youtube.png)