Checkpoint Cinema: Mohammed Almughanni on “An Orange from Jaffa”

An Orange from Jaffa (Mohammed Almughanni, 2024).Mohammed Almughanni is a young filmmaker from Gaza, Palestine, whose breakthrough short film, An Orange from Jaffa (2024), won the Grand Prix at Clermont-Ferrand last year and was subsequently shortlisted for an Academy Award. The narrative involves a young Palestinian man with an EU residency card and an older taxi driver whom he convinces to take him through a checkpoint. As IDF soldiers refuse their entry, the two men are forced to wait for hours in humiliation and anxiety—a situation that spirals until they are absurdly fighting physically with each other.Almughanni is now working on his first feature, a documentary that builds on his short-subject Son of the Streets (2020), set in Shatila refugee camp in Beirut. It follows Khodor, a thirteen-year-old boy, was born out of wedlock to a young mother and a 70-year-old man. Because his birth was not documented, he can’t go to school or leave the camp.Almughanni’s films, whether documentary or fiction, look at the lives of Palestinian people—both in Palestine and in the diaspora—without flinching. These are stories of interpersonal relations weathering heat, love, and distress; assemblages of everyday moments that show the incredible resilience of a besieged and beleaguered people.NOTEBOOK: I wanted to start by asking you about your childhood in Gaza and how you ended up becoming a filmmaker. Did you have a dream of making films?MOHAMMED ALMUGHANNI: I think it started when I was very little. I was born and lived in Gaza until the age of seventeen. As a child, I was always watching and listening to stories in the hood. I was also very attracted to cartoons that had a narrative, a story that builds up. There was a cartoon that I used to get up at 5 a.m. to watch: it’s an Italian-Japanese anime called Bye Marco in Arabic, or 3,000 Leagues in Search of Mother in English. There were a lot of cartoons from all over the world on Arabic TV when I was growing up: from Japan, from Europe, from the States.And then there were the stories of the people. As a child in Gaza, I would go with my uncle to the family council. He was a mediator, which meant that he was fixing issues between people. He would sit with total strangers discussing their personal and interpersonal issues. As a child, maybe I couldn’t understand anything about the issues themselves, but I could see the emotions of the people. I was keen to know more and to understand more—and I was always interested in listening to any kind of story.NOTEBOOK: Interpersonal issues like those really come out in your films. What does that mediation look like? Is your uncle still doing that?ALMUGHANNI: My uncle is still doing that, yes, even now, during the war. This tradition comes from the time of the British Mandate in Palestine. The British didn’t care about people’s social issues in Palestine. They only cared if Palestinians were attacking the colonizers—at that time, the British—and then they would jail them; if a Palestinian would kill a Palestinian, they wouldn't really care. So, a tradition called Mukhtar, or Makhatir—heads of families—started in Palestine. The head of family, the Mukhtar, is usually a wise person who acts as mediator. If someone from the family is making trouble, the head of the family is responsible for fixing the issue.My uncle is one of the most well-known mediators in Gaza. We have a family council for my family, the Almughanni family, that is supposed to fix the issues mainly within the family or with other families. But since we were not really having a lot of trouble within the family, my uncle was mainly fixing issues in other families within our council. So, as a child, I ended up listening to stories not from the Almughanni family, but from other families. They would sit down and talk. Sometimes they would even be screaming. My uncle has a very tough personality, so he would really use his authority to fix the issue—without the need for calling the police, of course. Even outside of Gaza, when people hear my name, they recognize my uncle because he has fixed so many issues for people in Gaza.I would love to make a feature fiction inspired by the stories I heard from him, the stories I experienced with him, stories of Palestinian social issues, and especially of people in Gaza; the internal issues of the people.An Orange from Jaffa (Mohammed Almughanni, 2024).NOTEBOOK: How did you end up going to the Łódź Film School in Poland to study film?ALMUGHANNI: When I was around twelve or fourteen years old, I started watching films from Europe, from Arabic countries, from the US. I would compare the characters in the films to these stories that I’d heard in the family council with my uncle and with the people in the hood: The story of that guy that I listened to the other day is similar to this story in the film; their issues are similar. I was wondering why we don't have films in Palestine that tell the stories and internal issues of people of G

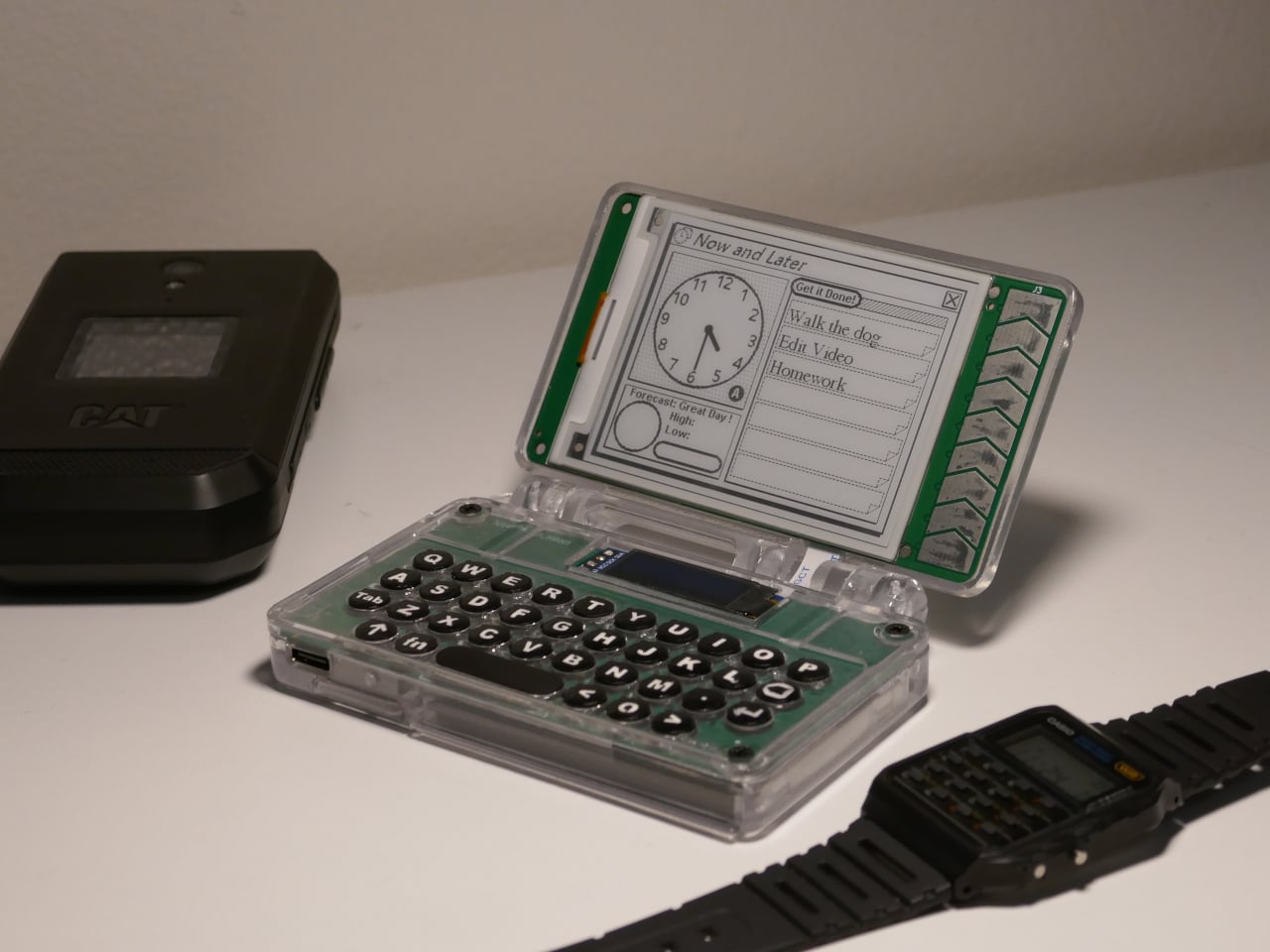

An Orange from Jaffa (Mohammed Almughanni, 2024).

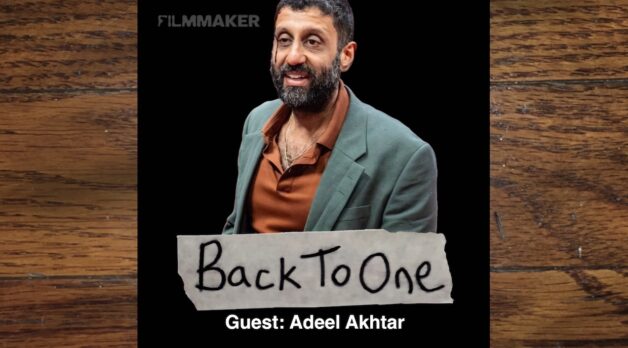

Mohammed Almughanni is a young filmmaker from Gaza, Palestine, whose breakthrough short film, An Orange from Jaffa (2024), won the Grand Prix at Clermont-Ferrand last year and was subsequently shortlisted for an Academy Award. The narrative involves a young Palestinian man with an EU residency card and an older taxi driver whom he convinces to take him through a checkpoint. As IDF soldiers refuse their entry, the two men are forced to wait for hours in humiliation and anxiety—a situation that spirals until they are absurdly fighting physically with each other.

Almughanni is now working on his first feature, a documentary that builds on his short-subject Son of the Streets (2020), set in Shatila refugee camp in Beirut. It follows Khodor, a thirteen-year-old boy, was born out of wedlock to a young mother and a 70-year-old man. Because his birth was not documented, he can’t go to school or leave the camp.

Almughanni’s films, whether documentary or fiction, look at the lives of Palestinian people—both in Palestine and in the diaspora—without flinching. These are stories of interpersonal relations weathering heat, love, and distress; assemblages of everyday moments that show the incredible resilience of a besieged and beleaguered people.

NOTEBOOK: I wanted to start by asking you about your childhood in Gaza and how you ended up becoming a filmmaker. Did you have a dream of making films?

MOHAMMED ALMUGHANNI: I think it started when I was very little. I was born and lived in Gaza until the age of seventeen. As a child, I was always watching and listening to stories in the hood. I was also very attracted to cartoons that had a narrative, a story that builds up. There was a cartoon that I used to get up at 5 a.m. to watch: it’s an Italian-Japanese anime called Bye Marco in Arabic, or 3,000 Leagues in Search of Mother in English. There were a lot of cartoons from all over the world on Arabic TV when I was growing up: from Japan, from Europe, from the States.

And then there were the stories of the people. As a child in Gaza, I would go with my uncle to the family council. He was a mediator, which meant that he was fixing issues between people. He would sit with total strangers discussing their personal and interpersonal issues. As a child, maybe I couldn’t understand anything about the issues themselves, but I could see the emotions of the people. I was keen to know more and to understand more—and I was always interested in listening to any kind of story.

NOTEBOOK: Interpersonal issues like those really come out in your films. What does that mediation look like? Is your uncle still doing that?

ALMUGHANNI: My uncle is still doing that, yes, even now, during the war. This tradition comes from the time of the British Mandate in Palestine. The British didn’t care about people’s social issues in Palestine. They only cared if Palestinians were attacking the colonizers—at that time, the British—and then they would jail them; if a Palestinian would kill a Palestinian, they wouldn't really care. So, a tradition called Mukhtar, or Makhatir—heads of families—started in Palestine. The head of family, the Mukhtar, is usually a wise person who acts as mediator. If someone from the family is making trouble, the head of the family is responsible for fixing the issue.

My uncle is one of the most well-known mediators in Gaza. We have a family council for my family, the Almughanni family, that is supposed to fix the issues mainly within the family or with other families. But since we were not really having a lot of trouble within the family, my uncle was mainly fixing issues in other families within our council. So, as a child, I ended up listening to stories not from the Almughanni family, but from other families. They would sit down and talk. Sometimes they would even be screaming. My uncle has a very tough personality, so he would really use his authority to fix the issue—without the need for calling the police, of course. Even outside of Gaza, when people hear my name, they recognize my uncle because he has fixed so many issues for people in Gaza.

I would love to make a feature fiction inspired by the stories I heard from him, the stories I experienced with him, stories of Palestinian social issues, and especially of people in Gaza; the internal issues of the people.

An Orange from Jaffa (Mohammed Almughanni, 2024).

NOTEBOOK: How did you end up going to the Łódź Film School in Poland to study film?

ALMUGHANNI: When I was around twelve or fourteen years old, I started watching films from Europe, from Arabic countries, from the US. I would compare the characters in the films to these stories that I’d heard in the family council with my uncle and with the people in the hood: The story of that guy that I listened to the other day is similar to this story in the film; their issues are similar. I was wondering why we don't have films in Palestine that tell the stories and internal issues of people of Gaza.

When I was fourteen, my father had to move to the West Bank to work. He was doing his best to get my mum, me, and my brothers and sisters out of Gaza, but due to the siege it was really difficult to get us out. It took him three years before he managed to get us out, too.

When I was fifteen or sixteen years old, I made my first film: a fifteen-minute short that I made with my best friend, Yousef Mashharawi, who is currently in Gaza. He really believed in what I was doing and was running with me in the sun from morning to sunset for three shooting days. I didn't have a script, just an outline of the scenes. We took a camera my father had left behind and went with three Palestinian parkour guys to the seashore of Gaza. That was my first short film. It wasn't great, but it was my first try. It was at this time that I started thinking about going to the Polish film school, which I knew about from my late uncle who had studied in Poland.

Later on, at the age of seventeen, we managed to go to the West Bank and reunite with my father. I would say I'm very privileged to leave Gaza—I'm within the two or three percent of people who managed to. Moving to the West Bank allowed me later to move to Poland. That’s how everything started.

NOTEBOOK: Have you been back to Gaza since you left at the age of seventeen?

ALMUGHANNI: I didn’t go back to Gaza during my studies. I was afraid that I wouldn’t be able to get back out of Gaza, as it can be difficult. Instead, I was trying to look for stories of Palestinians in Europe, in Cuba, in Lebanon, in Jordan. Even An Orange from Jaffa is set in the West Bank, which I could have access to. I still dream of going back to Gaza, the place that initiated my passion for filmmaking. I hope I will be able to go to Gaza and make those films that I wanted to make as a child.

Since I left for my studies, I managed to come back twice. Once was in 2015, when I made a twenty-minute short film called Shujayya. I only had seven days to stay in Gaza. I felt embarrassed that I'm coming to Gaza with a camera instead of to spend time with my family. The second time was eight years later, in 2023, just before October 7. This time I wanted to spend time with my sister, my uncles, my aunts, and my grandmother, and plan my next move so I could get permission to get film equipment in—you can’t even get a phone charger into Gaza, only the cable, so cameras are really difficult—and settle there for up to a year. I left ten days before October 7. You know what happened next: now there is a genocide.

Son of the Streets (Mohammed Almughanni, 2024).

NOTEBOOK: I wanted to ask you about Son of the Streets. What I really liked about the film is how it tackles a very difficult subject with nuance and honesty. Khodor is not the perfect child, but he is very relatable and blatantly himself. There’s so many layers of abuse in this story with the pervasive oppression of life in the refugee camp exacerbating everything else. How do you approach filming this kind of topic and dealing with the discomfort you mention of coming in with a camera?

ALMUGHANNI: It's really important to build trust with your characters and actually care for their story, not because of the film but because you actually care for their story, for sharing it with the world for them, and for people with similar stories or issues—that's why you decided to make a film about it. Editors often tell me that I don't have many hours of material, but I really have strong material. I spent months in Shatila, and most of the time I was just talking to the people: having tea, making friends. I wasn't following them with my camera all the time, I followed them mainly when I needed to and felt comfortable to do so. So, this connection and this intimacy and trust that you build with your characters is very essential. They have to trust you, you have to trust them.

The most important message of the film is the situation in a camp in Lebanon: you have a lot of social problems that come out of the circumstances as people are really packed into one square kilometre. I’m still in touch with Khodor and his family. Now that he’s eighteen I’m working on making a feature documentary about his story.

NOTEBOOK: What did Khodor think about the film?

ALMUGHANNI: I sent him the link, but I doubt that he saw it all—maybe he saw some scenes. He was happy: “Look at me with the birds...” But he didn't really comment. [Both laugh.]

Son of the Streets (Mohammed Almughanni, 2024).

NOTEBOOK: How autobiographical is An Orange from Jaffa?

ALMUGHANNI: It’s not a coincidence that it's about a character named Mohammed, originally from Gaza but now coming from Poland with a European residency card. So, yes, it's based on a true story—even though I would say the real story was much more dramatic. Initially I was going to have a different name for the character and a different country—I used the name just for the writing process, but then with the stress of filming and preproduction, I didn't have time to change it, so it remained like this.

NOTEBOOK: The film has been quite a success. What do you think others have responded to about it?

ALMUGHANNI: I make films that should be coming out of my heart—and this film was totally from my heart. There's also so many details in the film: of the situation in Palestine, of how dynamics work, of how everything is expressed. I spent a lot of time and energy implementing these little details, explaining why every move has to be in a specific way to make everything realistic. That’s what drives me and influences me the most: small, detailed, intimate stories from Palestine that people don’t know. So that even people who don't know anything about Palestine can come a little closer to Palestine.

![First Stills from Indie Slasher ‘The Last Sleepover’ Starring Felissa Rose Revealed [Exclusive]](https://bloody-disgusting.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/lastsleepover-scarlett2.jpg)

![Marvel Preview: Scarlet Witch Returns In TVA #5, Complicating Her MCU Status [Exclusive]](https://www.slashfilm.com/img/gallery/marvel-preview-scarlet-witch-returns-in-tva-5-complicating-her-mcu-status-exclusive/l-intro-1745521905.jpg?#)

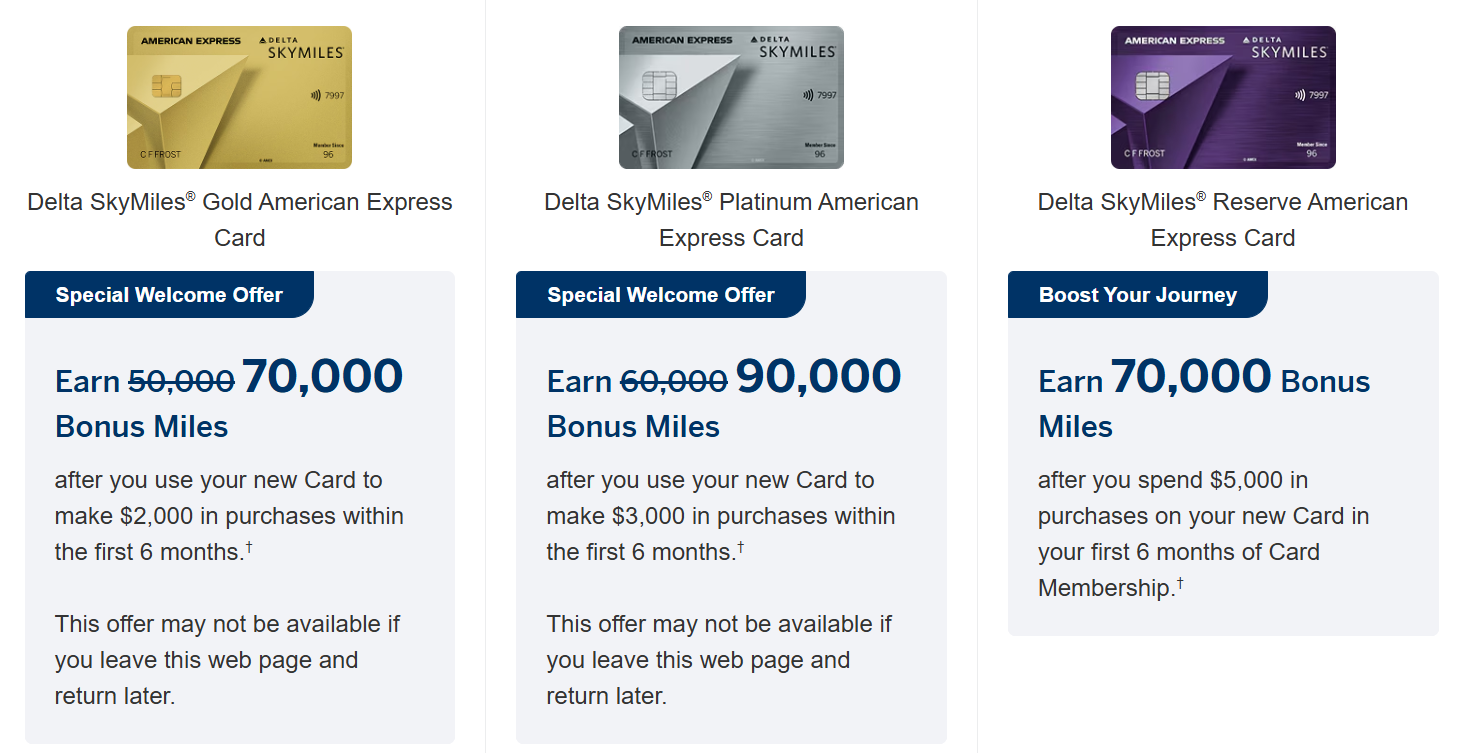

![[OFFER BEING PULLED]: The No Annual Fee Card That Makes Your Spending More Valuable Has A New Offer](https://boardingarea.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/ca0da65a6825b96f2f973660e5930464.jpeg?#)

![Last Chance Before Southwest Ends Open Seating: 90s Legend Kato Kaelin’s Barf Bag Hack Scores Empty Middle Seat [Roundup]](https://viewfromthewing.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/kato-kaelin-southwest.jpg?#)

![[Podcast] Unlocking Innovation: How Play & Creativity Drive Success with Melissa Dinwiddie](https://justcreative.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/melissa-dinwiddie-youtube.png)