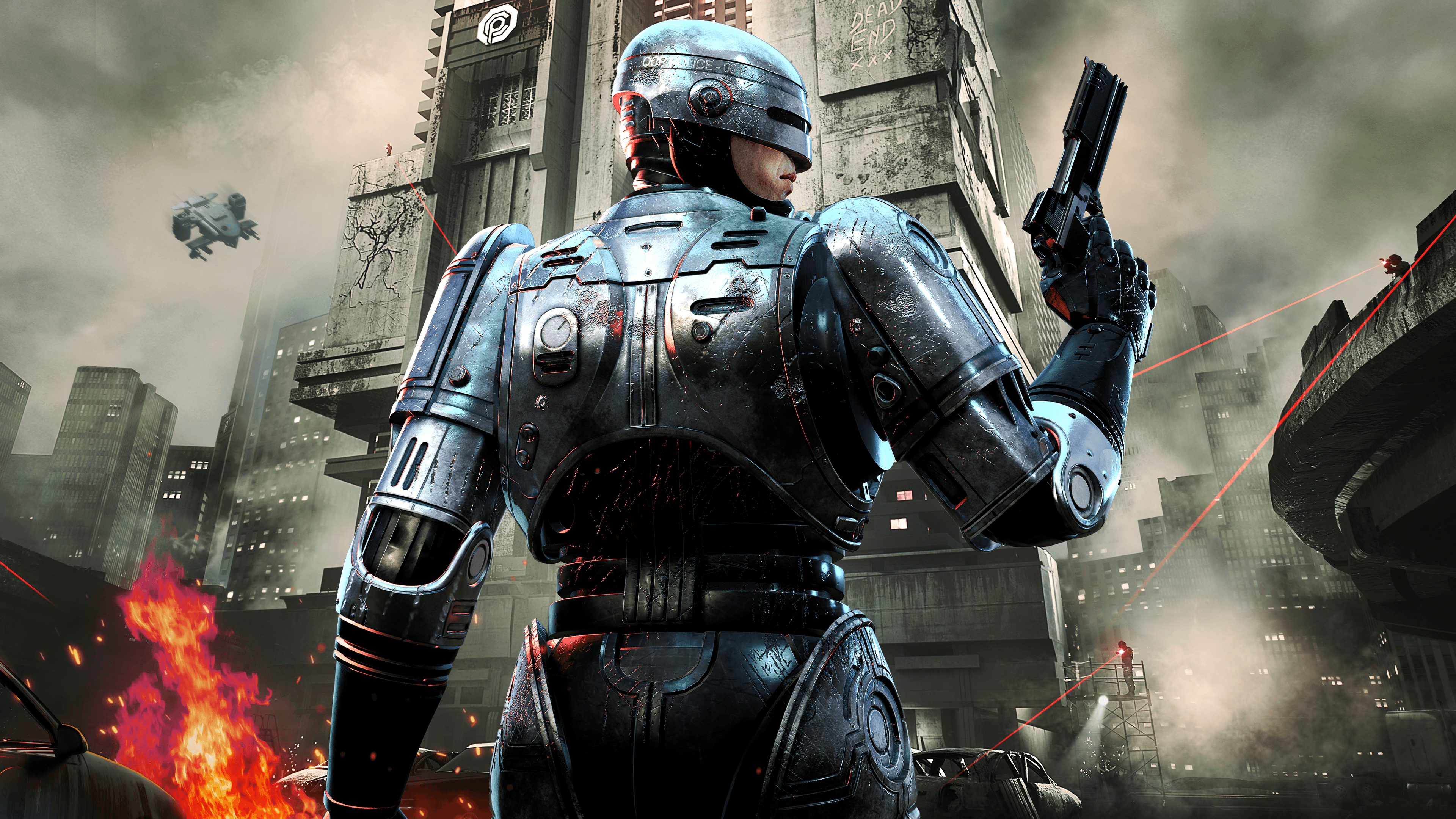

Havoc Ending Explained: How The Raid Director Redefines the Gritty Cop Movie

This article contains full spoilers for Havoc. For all the blood and guts and general nastiness it contains, Havoc is toughest to watch in its first three minutes. That’s when we watch as Detective Walker sits pensively and thinks about what he’s done. Under a monologue about tough choices made for one’s family intercuts shots […] The post Havoc Ending Explained: How The Raid Director Redefines the Gritty Cop Movie appeared first on Den of Geek.

This article contains full spoilers for Havoc.

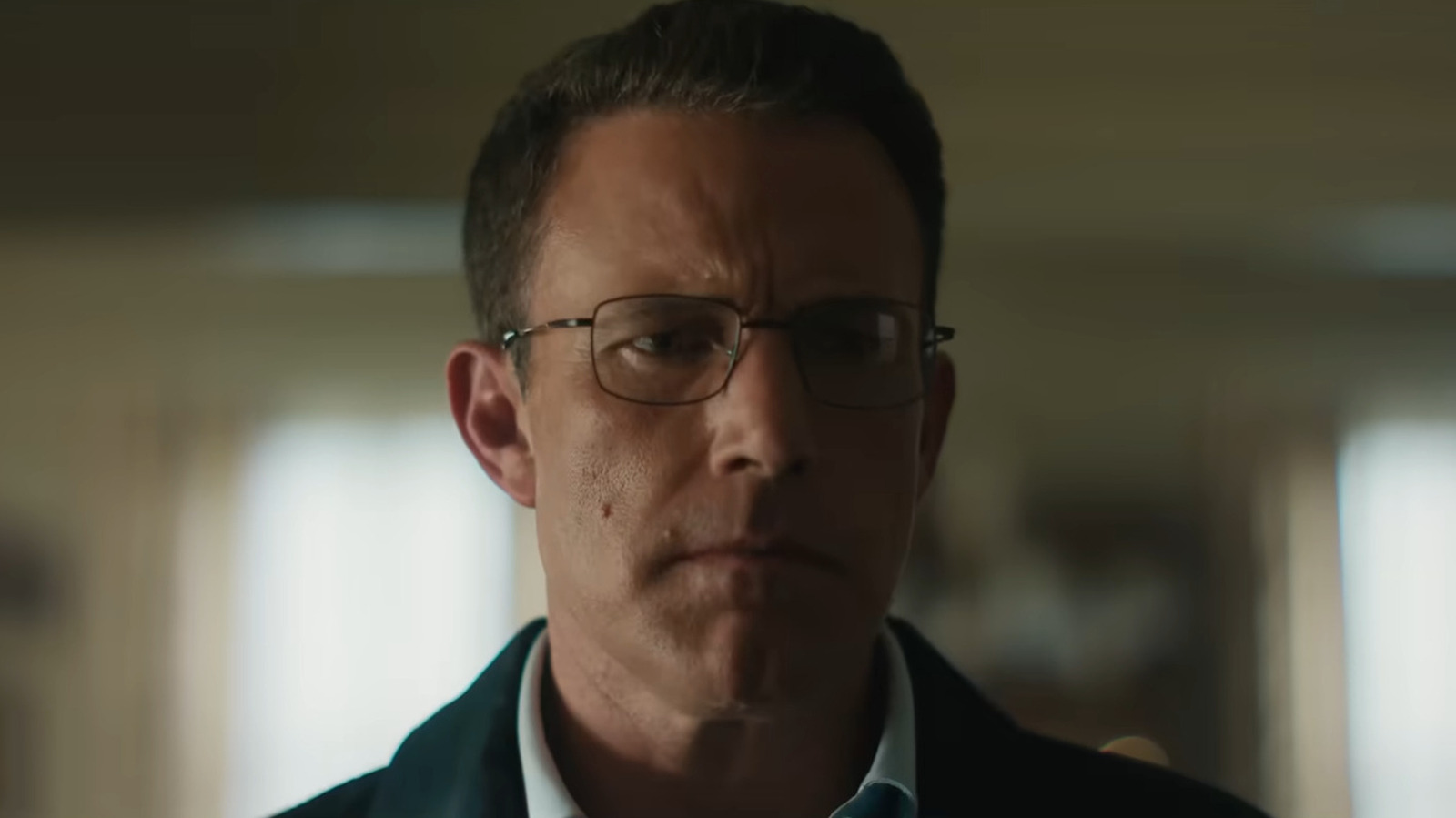

For all the blood and guts and general nastiness it contains, Havoc is toughest to watch in its first three minutes. That’s when we watch as Detective Walker sits pensively and thinks about what he’s done. Under a monologue about tough choices made for one’s family intercuts shots of Walker gearing up for duty, pulling out his badge and service revolver, and shots of Walker stealing cash from a drug bust and standing over a bloody victim.

Right away, Havoc establishes itself as yet another movie about a morally conflicted cop, a tough guy haunted by his compromises and redeemed by the love of his family and/or some last minute moment of heroism.

We’ve seen these types of stories a million times before, in the silent hagiography The Adventures of Lieutenant Petrosino (1912) and noir classics The Big Heat (1953) and Touch of Evil (1958). We saw it when The French Connection and Dirty Harry brought cops to New Hollywood in 1971 and when Lethal Weapon and 48 Hrs. gave the genre a slick ’80s sheen. We’ve seen it continue in more recent greats Heat, Training Day, and The Departed.

But by the time Havoc reaches its excessive conclusion, writer and director Gareth Evans has redefined the gritty cop genre, burying any pretenses to nobility under mountains of bullet casings and oceans of blood.

A Bad Cop in a Bad World

Havoc condenses a whole crime epic into a propulsive 105 minutes. Late in the holiday season in some undefined American city, a quartet of small-time hoods are chased down the highway by police. In desperation, two of the hoods throw their stolen merchandise at the cop car closest to them, hurling a dryer into the persuing vehicle. The appliance smashes through the cop car windshield, exploding not with just glass and plastic, but also mountains of cocaine.

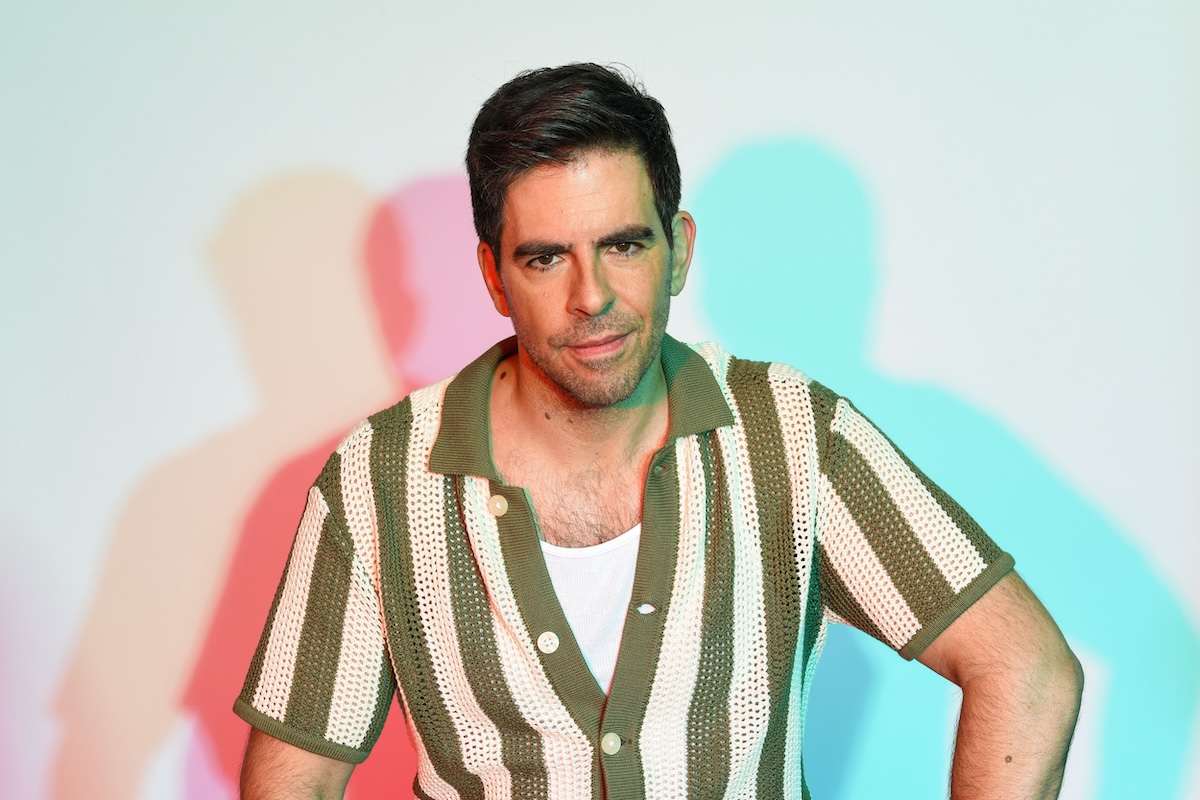

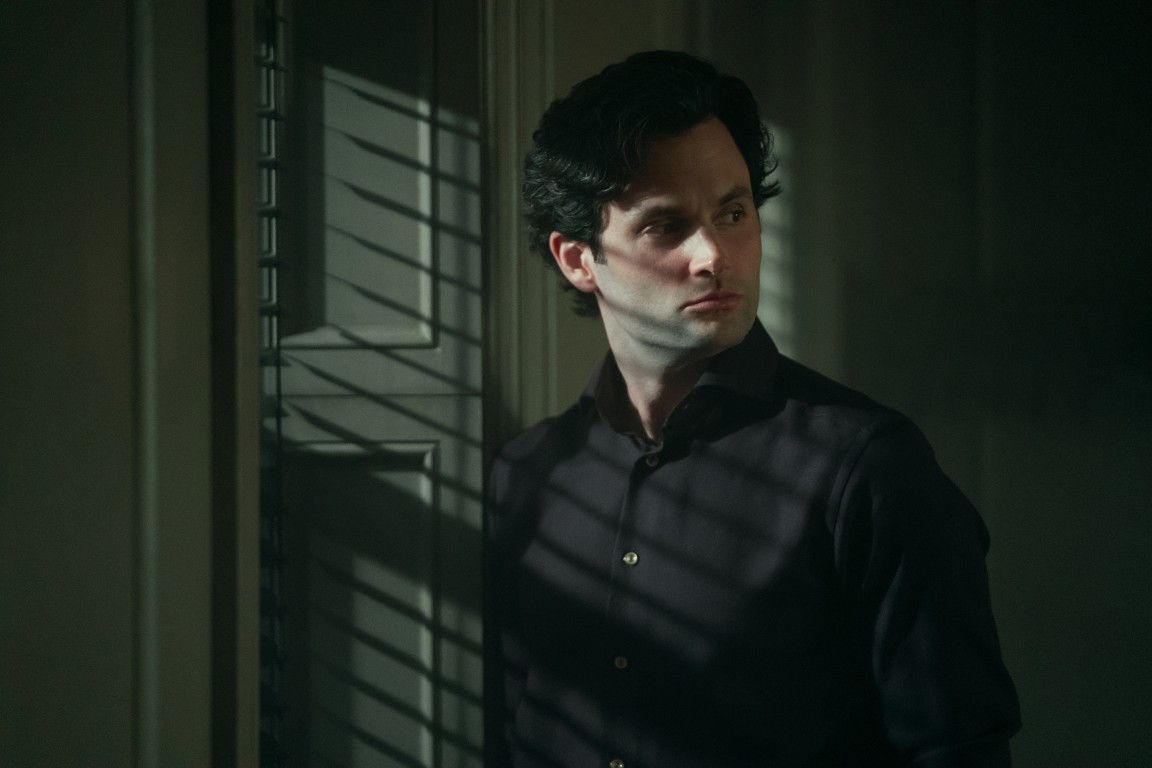

Upon seeing the attack upon his fellow officer, lead cop Vincent (Timothy Olyphant) and his men trace the cocaine to its source, Chinatown gangster Tsui (Jeremy Ang Jones), and open fire. The hoods escape the melee, but when when Walker (Tom Hardy) arrives, he recognizes one of them as Charlie (Justin Cornwell), son of crooked and powerful politician Lawrence Beaumont (Forest Whitaker).

Beaumont offers Walker a deal. He can get Charlie out of the mess without it getting to the press, Walker will be out of Beaumont’s debt. Walker has to find Charlie before the others looking for him, including Tsui’s vengeful mother (Yeo Yann Yann), her duplicitous right hand man Ping (Sunny Pang), and Vincent and his gang of cops. Making things even harder is Walker’s idealistic younger partner Ellie (Jessie Mei Li), who doesn’t realize the depths of his darkness.

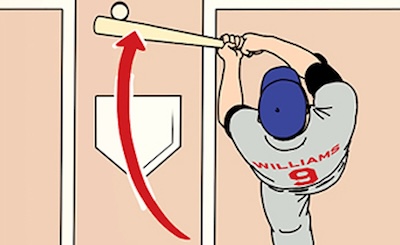

That plot gives Evans plenty of space to do what he does best, craft visceral fight scenes. Evans broke out with 2011’s genre-defining martial arts movie The Raid: Redemption, which brought Indonesian action to the West and paved the way for the John Wick franchise. Certainly, that type of hand-to-hand combat occurs in Havoc, especially in a glorious extended fight sequence that occurs halfway through the film. When Walker, Vincent, a silent Chinese assassin (Michelle Waterson) and their respective gangs descend on Charlie and his friends in a club, an eight-minute fight breaks out, starting with Chinatown gang members battering cops with batons and ending with a gunfight that spills out into the streets.

Evans adds to his repertoire new ways of depicting carnage, including the aforementioned movie car chase, shot with just the same immediacy as the combat scenes. But the most notable addition is the use of gun violence. Gun shots have rarely been louder in a movie, rivaling those in Alex Garland‘s Civil War and Warfare. People don’t get shot just once; they’re peppered with bullets, convulsing as they’re filled with lead. The blood appears to be digital, instead of the practical squibs of previous eras, but that allows Evans more space to show how bodies can be destroyed in various ways.

As that description might suggest, Havoc makes for a bleak film, both in form and content. It’s not just that everyone in the film is a killer, it’s not just that the violence is spectacular and constant. That unpleasantness that transforms the ending from something rote to something transcendent, unique among the grittiest cop movie.

A Violent End

At Havoc‘s climax, Charlie has been caught. A battered Walker cannot stop them, so Tsui’s mother and Ping arrive to execute their vengeance. They’re halted only Beaumont, who throws himself in front of Charlie and takes the bullet for his son. The gesture pauses the action, but only enough for the truth to come out, that it was Ping who betrayed Tsui and Vincent who killed them, leading to another shoot out that even sees Charlie grabbing a machine gun and slaughtering his enemies.

After the shooting stops, Walker’s left with Vincent. Although Vincent tries to get Walker to leave, pointing out that anyone who knows what he did has been killed, Walker disagrees. He shoots Vincent, the true last person who knows his guilt, and stumbles away.

Havoc ends at it begins, with Walker sitting alone and contemplating what he’s done. When Ellie arrives to reassure him, Walker refuses, telling her to arrest him instead.

“You’re a good cop, Ellie,” he says. “I probably should have been nicer to you.” As she takes in his words, we see flashing lights in the distance, police cars arriving to bring order to the scene. Their lights illuminate Ellie and Walker in their final moments, in which the latter promises to bring Walker’s daughter his Christmas present, a couple of trinkets he bought from a convenience store at the start of the movie, but he refuses. “I don’t want to disappoint her.”

With that rejection, Havoc avoids the trite hope that even gritty cop movies embrace, the idea that redemption waits for the bad cop through some later generation, in this case Ellie or the daughter. But Havoc gives Walker no such hope, nor do we trust that Ellie will be better — after all, she’s introduced in the movie brutalizing a suspect who falls outside of her investigation.

The movie ends with a push in on Walker’s face, highlighted by red and blue lights. These highlights, combined with the nastiness of the movie that preceded it, underscore Havoc‘s contribution to the canon of gritty cop movies. Walker isn’t a corruption of a noble institution. He’s the embodiment of a violent, corrupt institution, one that won’t be changed by “good cop” Ellie. All of the chaos of the movie is a standard part of Havoc’s world, a world few cop movies would dare to enter.

Havoc streams on Netflix on April 25.

The post Havoc Ending Explained: How The Raid Director Redefines the Gritty Cop Movie appeared first on Den of Geek.

![‘Thorns’ – ‘Hellraiser’ Inspired Horror Movie Starring Doug Bradley Releases in May [Trailer]](https://bloody-disgusting.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/04/thorns.jpg)

![Hotel Beds Outperform Your Master Bedroom for Better Sex—Here’s Why [Roundup]](https://viewfromthewing.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/burj-al-arab-bed.jpg?#)

.jpg?#)

![[Podcast] Unlocking Innovation: How Play & Creativity Drive Success with Melissa Dinwiddie](https://justcreative.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/melissa-dinwiddie-youtube.png)