How George A. Romero’s ‘The Amusement Park’ Went from Lost Media to a Graphic Novel [Interview]

Shudder unearthed George A. Romero‘s long-lost The Amusement Park back in 2021, a previously unseen nightmare that Romero made back in the early 1970s. The 60-minute film was actually a PSA on age discrimination that Romero was hired to make early in his career, filmed for TV but never actually released – until Shudder finally brought it […] The post How George A. Romero’s ‘The Amusement Park’ Went from Lost Media to a Graphic Novel [Interview] appeared first on Bloody Disgusting!.

![How George A. Romero’s ‘The Amusement Park’ Went from Lost Media to a Graphic Novel [Interview]](https://i0.wp.com/bloody-disgusting.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/Cross.jpg?fit=1200%2C904&ssl=1)

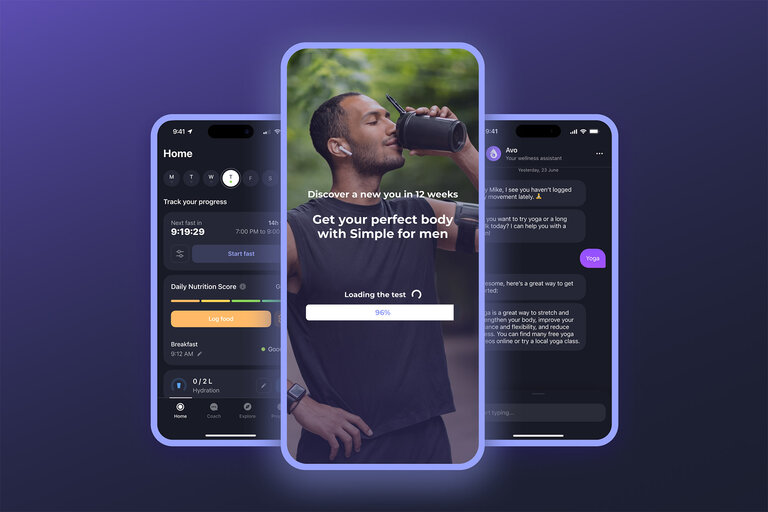

Shudder unearthed George A. Romero‘s long-lost The Amusement Park back in 2021, a previously unseen nightmare that Romero made back in the early 1970s. The 60-minute film was actually a PSA on age discrimination that Romero was hired to make early in his career, filmed for TV but never actually released – until Shudder finally brought it to light.

Now, The Amusement Park has been turned into a graphic novel by Storm King Comics!

George A. Romero’s The Amusement Park becomes an original graphic novel this summer when Storm King Comics releases John Carpenter Presents George A. Romero’s The Amusement Park, an all-new artistic interpretation of the unique film. It’ll be available for purchase online, at comic book stores, and at book sellers on June 10, 2025.

Long thought to be lost, and originally conceived as a public service announcement, The Amusement Park is a surreal, haunting commentary on ageism and society’s treatment of the elderly, wrapped in Romero’s signature horror style. The George A. Romero Foundation, which is dedicated to honoring the life and preserving Romero’s work, restored the film as one of its first projects, and discovered the result met with widespread critical acclaim.

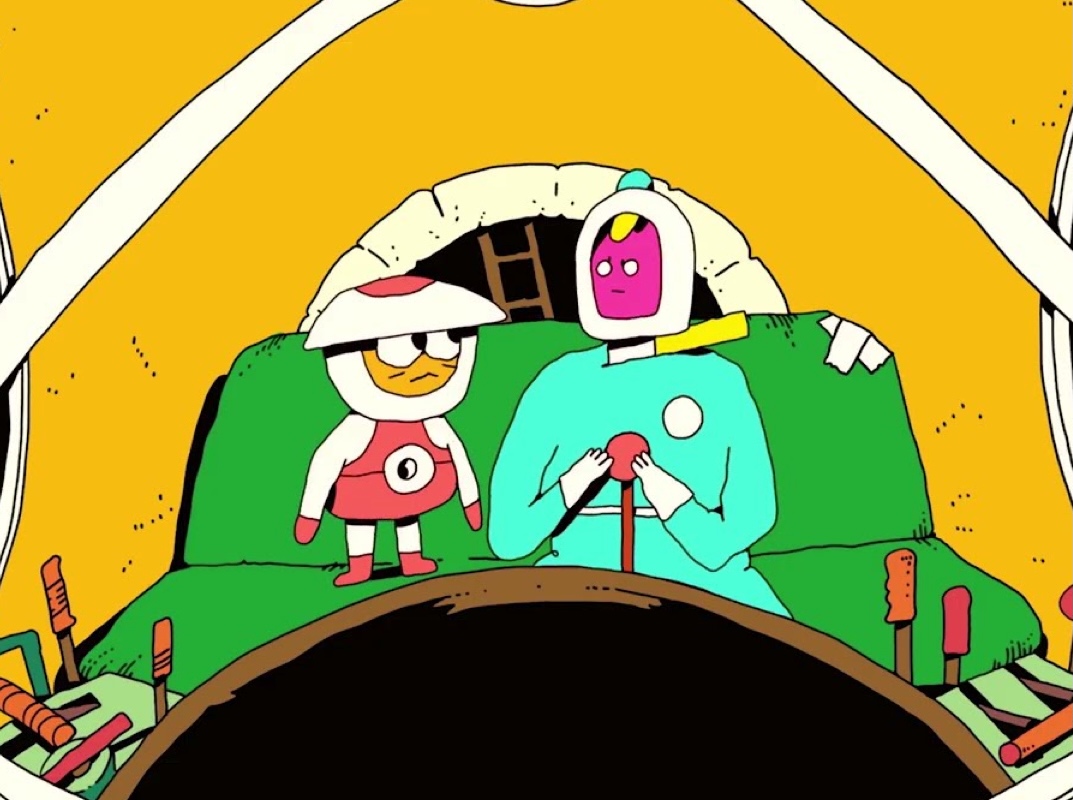

As critics and audiences pored through the myriad of images and meanings found in The Amusement Park, the Foundation and its artist-in-residence, illustrator Ryan Carr, began working on adapting the film in a novel way—a graphic novel way. Along with writer Jeff Whitehead, a visually stunning interpretation of the film came to life on the page.

Read on for an exclusive interview with Whitehead and Carr to learn more.

Bloody Disgusting: How did your relationship/work with the George A. Romero Foundation (GARF) come about?

Bloody Disgusting: How did your relationship/work with the George A. Romero Foundation (GARF) come about?

Ryan Carr: My work with the George A. Romero Foundation began during 2020 lockdown. I had been drawing a lot of monsters just for myself during Covid and when I had drawn a pen and ink portrait of Bub the foundation noticed it on Instagram and asked to share it in their newsletter. I then was asked to do a few more illustrations (including a title header for a chapter of Outpost 5 that George had written himself!) and it snowballed from there. I love working with the team and everyone has been so supportive with me and my work.

Jeff Whitehead: I came into the horror community through writing, having optioned a feature to a producer who has become a close friend. He introduced me to a professor named Adam Lowenstein at the University of Pittsburgh who specializes in horror studies. Adam had met Suzanne Desrocher-Romero after George’s untimely death through a city-wide celebration in his honor. At that time, she told Adam that she was creating a foundation to preserve George’s legacy. Adam thought of me given some of the work I had done managing people and projects throughout the non-profit space. I connected with Suz and the rest of history.

BD: George was known not just for horror, but for embedding sharp social critique in his work. How did you ensure that those themes were preserved, or even expanded, through the lens of the graphic novel?

Whitehead: My favorite horror works are those that present social themes in an accessible way for a mass audience, so my first priority was to make sure that all of the social commentary that was packed into the film made it into the adaptation to graphic novel. I also challenged myself to provide an extended story so that the audience could ‘see’ through the plot what Lincoln Maazel was saying in the public service announcement portions of the film. I also wanted to modernize a part of the story so that it would not feel to a modern audience as if it were locked away in 1973. Part of George’s genius was his ability to find social commentary that is timeless. This treatise on aging is as relevant today as it was fifty years ago, if not more so.

BD: Was there any pressure or responsibility you felt when working on this, particularly knowing how deeply Romero’s fans and legacy are tied to his vision?

Carr: ABSOLUTELY. I put a ton of pressure on myself to stay as faithful to George’s source material as I could. Using the film as a reference point but also other films in George’s catalogue make their way into the book as well. This is definitely a different medium so a few things had to be altered for the visual format here but overall I feel like it stays true to the film. I know a lot of this has to do with Jeff’s adaptation which always kept me on the right path.

Whitehead: Yes, enormous pressure. But I love pressure, so I challenged myself to create a story that extended what George created. When we had finished restoring the film, we knew that we couldn’t make changes to it to modernize it. But we could pull the themes forward fifty years through the graphic novel medium.

BD: The GARF works to preserve and elevate independent genre filmmaking. Do you see The Amusement Park graphic novel as part of that mission in spirit, and if so, how?

Whitehead: I do as it will also enhance the visibility of the film. Aside from a few screenings over the years, this work of George’s has not had the visibility that it deserves. The Amusement Park offers audiences another opportunity to see George tackle a societal issue in an inventive way. But it was not intended to function as a feature film. Instead, it was commissioned as a public service announcement on elder abuse. Our hope is that the graphic novel will help increase visibility for The Amusement Park itself, but also for George’s work. We all believe that George’s work is timeless, and by leveraging different mediums, we hope that we can bring George’s work to new audiences and generations.

BD: Were there any unexpected discoveries or emotional moments you had when working on this project?

Carr: There were definitely a few scenes that surprised me when we expanded them to a script and drawings, the first may have been the outdoor dining scene. Jeff and I really got cooking on how to lend visuals that weren’t necessarily in the film but got the point across to the viewer. Adding in some aging outsiders who were hungry for Lincoln’s meal really got across that he not only felt guilty in that moment but relate to them as they were being treated as outsiders. And then we really went to town on the zombie references as they swooped in and ate his meal, which was a total blast. You get a sense of it in the film but here we could make sure it was just loud enough.

Emotionally the scene at the end where Lincoln reads to the child gets me every time in the film, and drawing it was tough for me. Illustrating this book took me a very long time, longer than I’d spent on any project before, and once I was there and illustrating that scene I knew the end was in sight, both for Lincoln’s story and my own time on this journey.

Whitehead: There are more easter eggs throughout the film than I expected. Cameos of the Romero creative family are sprinkled throughout. As there was no script like we would be accustomed to seeing today, I actually started the project by going frame by frame to ensure that I captured everything that was said in the film itself. The production team was largely working from what looked more like a modern treatment or synopsis, so much of the film itself is ad-libbed. Although a painstaking process, it also showed how terrific the Romero creative family really was. Having grown up with the films, it was fulfilling to see the creative family binding together to make a special piece of work.

BD: Ryan, how did you approach translating George’s tone and storytelling style visually?

Carr: I love the visual style of The Amusement Park. There’s something in the quick edits and wide angle distortions that becomes really visually nightmarish. I tried to keep that element in there as much as I could, warping things when I could. I do enjoy drawing a lot of detail and wrinkles so in a story about ageism I’m sure I played that up to the best of my abilities.

I think one thing I thought a lot about was color and using it in place of music or sound effects. When the color ramps up in the book I felt like it was to keep things loud visually and play up mood and horror when it was appropriate.

BD: Jeff, how do you hope this graphic novel contributes to the broader understanding or appreciation of George’s legacy, particularly with the GARF?

Whitehead: It is now pretty widely known that George was more than just a horror filmmaker. He was an independent filmmaker deeply entrenched in the nuances of the craft. The Amusement Park graphic novel is an example of a George piece that is scary for vastly different reasons than the films which made him a household name in the horror genre. George transcended the genre in a way that is not always as appreciated as we believe it should be. Particularly in light of what we are doing to preserve George’s legacy and share it with future generations, we are optimistic that by showcasing pieces like The Amusement Park, there will be a greater appreciation for the depth of George’s talent and vision.

BD: Ryan, were there any elements or scenes in the film that you were most excited to translate visually?

BD: Ryan, were there any elements or scenes in the film that you were most excited to translate visually?

Carr: The biker attack scene was something I thought about a lot building up to it, as it plays as the big violent moment in the film and definitely in the book. One of the first things I drew in preparation for this was a shot of the biker gang with death standing behind them, so once I got to that scene I felt ready to play it up as loud as I could.

BD: How did working on this project reshape or deepen your own relationship to George’s body of work?

Carr: I can probably say that at this point I’ve watched The Amusement Park film more than most people on the planet and I’ve only grown to love it more and more. I feel deeply tied to each scene and each nuance after having studied it for years now. If anything too it’s led to me looking at all of George’s films especially those done throughout the 70’s and appreciate them more than ever. The editing style and decisions in Martin or The Crazies or Season of the Witch is some of my favorite stuff on screen. I think beforehand I was more in tune with his undead work but he has treasures upon treasures to enjoy with so many other subjects.

Whitehead: I have always have a deep appreciation for George – he has been a hero of mine since I was a child watching Night, Dawn, and Day at sleepovers with my best childhood friend. Even then, we could appreciate the social context in which George’s work was positioned. However, given the fact that I grew when the internet was in its infancy and was an adult when social media came throttling into all of our lives, we did not have as much access to work that was considered lost or shelved. I had never seen The Amusement Park until we started working on the restoration. Throughout the entirety of my college days, there were whispers of a ‘lost Romero’ as there are whispers of lost films of all of the masters of their art. However, we had no way to find it. Until the Foundation managed to secure several prints. We were floored by the film as it extended George’s body of work in the 1970s as he was really charting his course. The Amusement Park is interesting on many levels as on one hand, this was a public service announcement that was designed primarily to keep the lights on and cameras rolling on the next projects. On the other, instead of just doing the assignment, George created a world and filled it with anecdotes that are still relevant today.

BD: What do you hope new readers (especially those unfamiliar with George’s film) take away from this adaptation?

Carr: The Amusement Park deals with ageism in a very unique way, something I felt was deeply appropriate during COVID when lockdown was in place in order to try take care of the more susceptible members of our society, and seeing those of us who were less than interested in that concept was very interesting. In this way I hope the message gets across that yes, even you will one day become old.

I do hope that new readers want to in turn visit some of George’s lesser known works and enjoy seeing an artist as they develop their ideas and aesthetic prowess. I’m honored to have worked on this project and I know Jeff and I put a ton of work and care into it.

Whitehead: I hope that new readers gain an appreciation for just how brilliant and visionary George was as a filmmaker. Whether he cared to admit it or not, his films are full of representations of social injustice, societal issues, and commentary on them that would have been challenging to embed in works from other genres. George very stealthily helped his audiences see what he wanted them to see. The Amusement Park is not subtle. It is an on-the-nose exploration of aging and death, told through the vignettes of an American icon, the classic amusement park. Designed for families as a safe place to have fun, George flipped this all on its head, making every new attraction something allegorical for his characters to fear. He claims the amusement park as his own, trapping us all within it whether we like it or not.

Look for John Carpenter Presents George A. Romero’s The Amusement Park on June 10.

The post How George A. Romero’s ‘The Amusement Park’ Went from Lost Media to a Graphic Novel [Interview] appeared first on Bloody Disgusting!.

![‘Scream’ Meets ‘Sleepwalkers’ in Shot-on-Video Slasher ‘Screamwalkers’ [Trailer]](https://bloody-disgusting.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/screamwalkers.jpg)

![Your New Found Footage Obsession ‘Project MKHEXE’ Hits SCREAMBOX Tuesday [Trailer]](https://bloody-disgusting.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/ProjectMkhexe-still.jpg)

![Havoc Director Gareth Evans Knows The Movie's Shootouts Are Unrealistic, But There's A Logic To Them [Exclusive]](https://www.slashfilm.com/img/gallery/havoc-director-gareth-evans-knows-the-movies-shootouts-are-unrealistic-but-theres-a-logic-to-them-exclusive/l-intro-1745607088.jpg?#)

.jpg?width=1920&height=1920&fit=bounds&quality=70&format=jpg&auto=webp#)

![[Podcast] Unlocking Innovation: How Play & Creativity Drive Success with Melissa Dinwiddie](https://justcreative.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/melissa-dinwiddie-youtube.png)