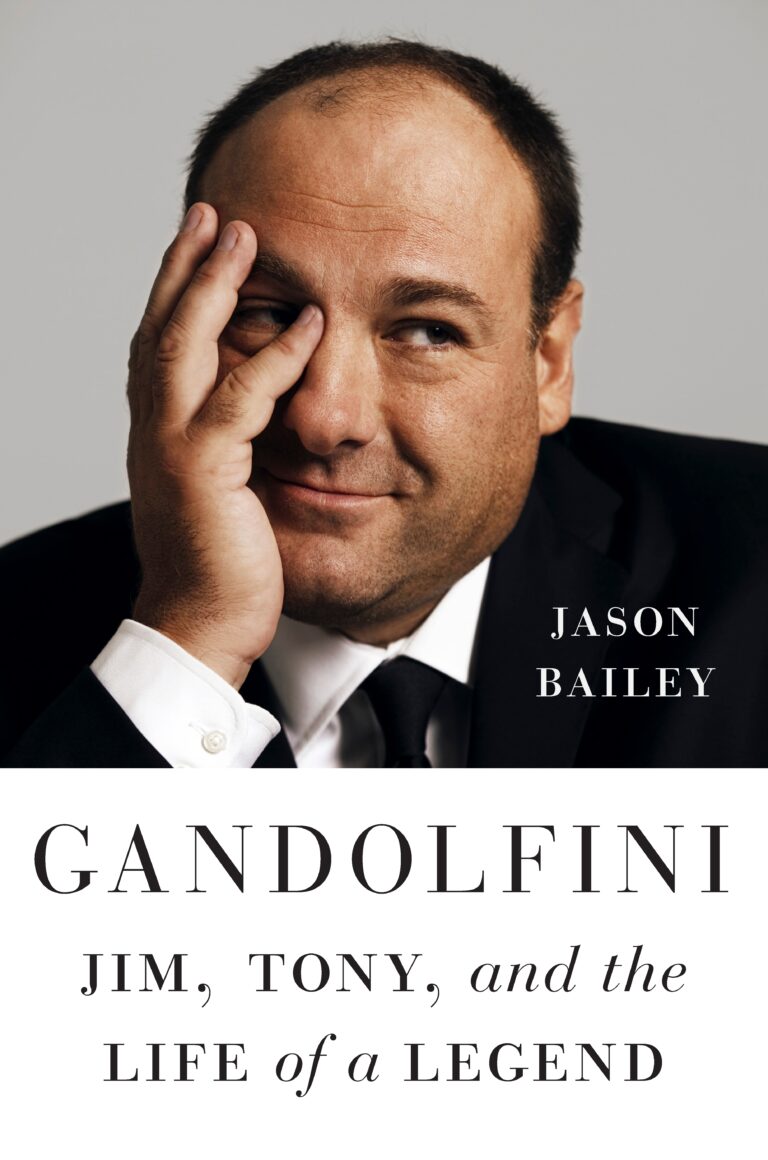

Book Excerpt: Gandolfini: Jim, Tony & the Life of a Legend by Jason Bailey

An excerpt from Jason Bailey's phenomenal new book.

We are incredibly proud to present an excerpt from the excellent Gandolfini: Jim, Tony & the Life of a Legend by Jason Bailey. The author of The Ultimate Woody Allen Film Companion and Fun City Cinema tackles the life and work of the star of “The Sopranos,” “True Romance,” and “Enough Said” with the perfect blend of curiosity and compassion. Gandolfini was a private man, one who insisted that the work could speak for itself, but Bailey gets to the root of what was so special about this incredible actor by examining the different aspects of himself he showed people throughout his life. A picture emerges of a man who wasn’t just naturally talented but worked constantly at his craft, elevating everyone around him. It’s a surprisingly moving biography, a piece that’s fueled by not just the artistry but the shared humanity of the author and the subject. It’s in stores tomorrow. Get a copy here and read an excerpt below.

Gandolfini quickly proved adept at maintaining the right, light mood on set. “The first thing I remember is he had to do a thing where he had a panic attack and collapses,” says Robert Iler, the young actor cast as Tony’s teenage son, Anthony Jr. “I remember he fell over and then we all are supposed to rush over, like, Oh my God, are you OK? And then we rolled him over, and he had a raw hot dog in his mouth. Everybody just started cracking up.”

Jim and Falco proved a good match, both in their on- screen repartee and the professionalism they exhibited to their castmates, many of whom were not as experienced. “Jimmy and Edie made everybody better,” Chase explained. “Both of them were extraordinary. And two totally different styles of working. Jimmy would argue about everything: I don’t know, this doesn’t work, why is he saying that, I don’t want to. Edie came in, had it all memorized. Never any discussion, just did it. And yet, look at, look at how well matched they seem. . . . They came to work and they did their job.”

The hour of television they created was strikingly unique, a perfectly executed little sixty-minute film. The structure of the episode was unlike the rest of the series, with Tony visiting Dr. Melfi for his first sessions, narrating and explaining his life to her, over cutaways and flashbacks to the events he describes. Some television actors take a few episodes to find the right notes for a character, but not Gandolfini; the shadings of Tony Soprano would grow more nuanced over the series’ run, but the foundations are firmly in place, specifically his danger (how he flips from giggling and cackling as he chases a debtor down to the fury and rage of the beating he administers) and his vulnerability (the tears he sheds over the loss of his ducks). Yet some of his most quietly powerful work is in the duet scenes with Bracco, as he carefully chooses what he will talk about, and what he will not.

But proof-of-concept pilots like The Sopranos’ are ultimately like another audition; a network can still, for any reason, choose not to take the show to series. This was news to relative newcomer Iler, whose family had been abuzz about the gig: “This is it, you’re gonna be famous, this is gonna be massive and huge.” When he said something to that effect in earshot of Tony Sirico, the older actor grabbed him and said, “Kid, do you know how many of these fucking things we do?”

“What do you mean?” Iler asked, confused.

“We’re never gonna see each other again,” Sirico informed him. “So have fun while you’re here, and we’ll all hang out and it’ll be nice, but don’t expect to ever see any of us ever again.” (“So then I had to go break that to my family,” Iler says.)

Sirico wasn’t the only one. “Nobody knew it was going to become such a behemoth,” says Alik Sakharov, cinematographer for the pilot and roughly half of the shows that followed. “But I do remember very distinctly, David and I used to share an office. And he would come into the office, and he would have this million-mile stare looking out the window, very quiet, so contemplatively being in his own world. One day I just asked him, ‘David, what’s up?’ He said, ‘I have no idea who the fuck is gonna watch this show.’”

That question loomed larger after Chase turned in the pilot to HBO in October 1997, and days turned to weeks while waiting for the response, which the network executives had to deliver by December 20. They weren’t just being coy; test screenings had gone poorly enough that many of the initial concerns about the show (its lack of stars, its cost, its antihero, its adult subject matter), and even its title (execs worried that it sounded like a show about opera singers) lingered. As his impatience grew— “David,” Susie Fitzgerald deadpanned, “is not a good waiter”— Chase developed a backup plan: If they rejected the pilot, maybe he could get them to put up enough extra money to turn it into the feature film he’d originally imagined, or even buy the pilot back from them and scrape the rest of the budget together himself. The cast went about their work; Jim went out to Los Angeles for the Remembrance run (and his night in the Beverly Hills jail), then to Massachusetts to shoot A Civil Action. “I remember us sitting down with him after we saw it,” Armstrong says of the pilot. “And we said, This will be the best work you’ve ever done that prob ably a lot of people won’t see. Because we thought, it’s not any of these network shows. Even if it gets picked up, a lot of people aren’t gonna be watching HBO. So he wasn’t sitting there waiting on pins and needles to hear if it was going. At all.” If anything, he was regretting taking the role to begin with. “He had concerns because his father, who was prob ably just jabbing him, said, I don’t think this is any good,” says Sanders. “And then he wanted to get out of it. Obviously he didn’t, because I’m sure he loved it. But he had a personality that always could come up with a better actor for a role, that typical thing, Maybe I shouldn’t be doing this— a lot of second- guessing of himself.”

Finally, on the day before the deadline, the network gave the order. “It was like a big Christmas present,” Imperioli said. The announcement hit Variety on January 12, 1998: “HBO has committed to its second- ever epi sodic drama series, ‘The Sopranos,’ a Mob- themed hour for which the Time- Warner cabler has purchased 12 episodes, plus the completed pilot, for a total of 13 installments.”

Excerpt from the new book Gandolfini: Jim, Tony & the Life of a Legend (Abrams Press) by Jason Bailey © 2025 Jason Bailey

![The History of the Universal Monsters: How ‘The Invisible Man’ Nearly Vanished Into Hollywood Limbo [Halloweenies Podcast]](https://bloody-disgusting.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/the-invisible-man-halloweenies.jpeg)

![[Dead] Japan Airlines First Class wide open through JetBlue TrueBlue (though it’s expensive)](https://frequentmiler.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/11/JAL-first-seat.jpg?#)

![Marriott Is Now Advertising Hotels In North Korea [Roundup]](https://viewfromthewing.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/ChatGPT-Image-Apr-27-2025-04_25_59-AM.jpg?#)