Adobe's Content Authenticity enters public beta, but with some flaws

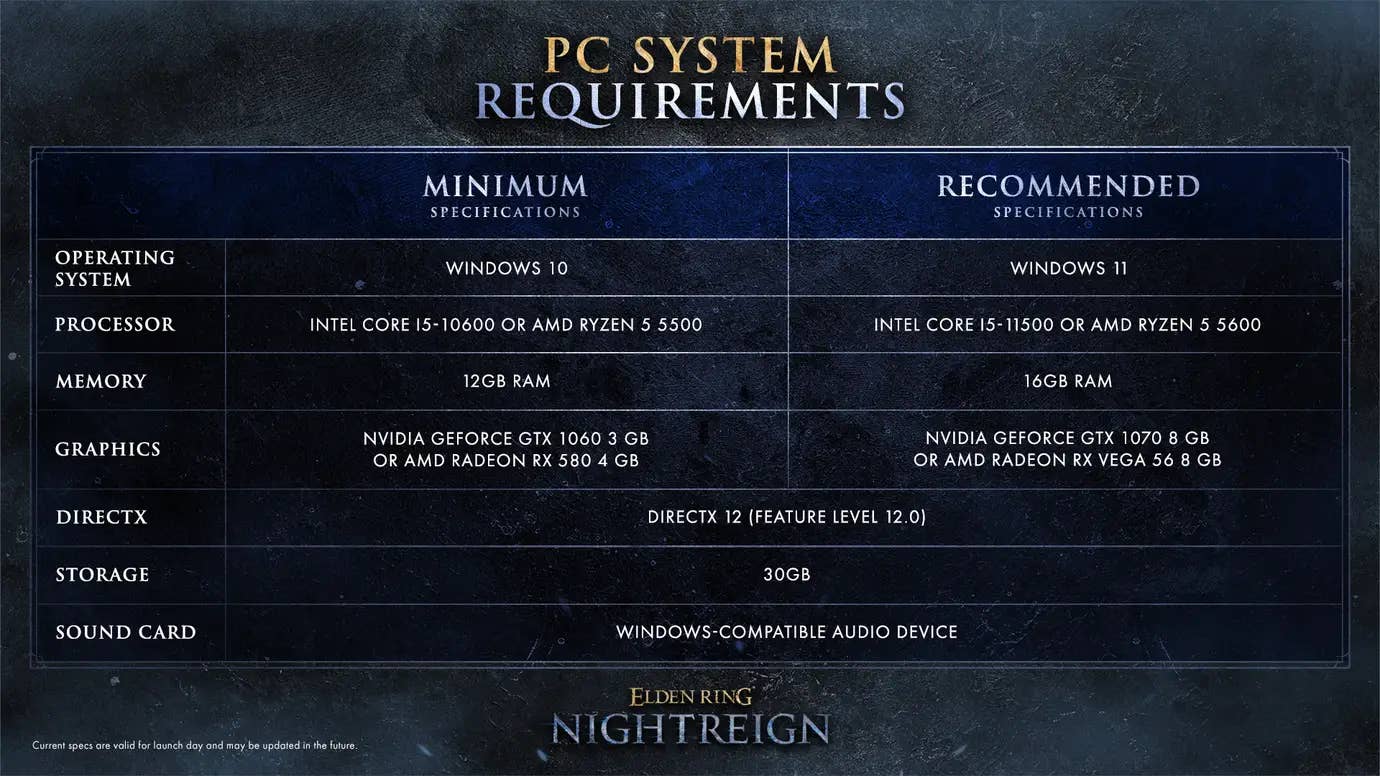

Image: Adobe Last week, Adobe announced that it's opening up the beta for its Content Authenticity app, which launched in private beta last year. This means more people will be able to access the tool's features, which let you add secure metadata to an image claiming that you own it and add a flag asking AI companies not to use it to train their models. That should be a good thing. But the current implementation could threaten to muddy the waters about what images are authentic and what aren't even further, which is the exact problem the tool was made to solve. If you're not familiar with the Adobe Content Authenticity app (and don't want to read the in-depth piece we wrote about it when it was launched), here's a quick summary: it's built around the Coalition for Content Provenance and Authenticity (C2PA) Content Credentials system. It lets you add a cryptographically signed piece of metadata that says you made the image. It can also link to social profiles on sites like Instagram, Behance, and, now, LinkedIn. A link to that metadata is also added as an invisible watermark into the image, so it should be retrievable even if someone screenshots it or strips its metadata. Let's do a quick compare and contrast, though. On the left is what those self-signed credentials look like when viewed in Adobe's inspector, and on the right is what they look like when they come from a camera that bakes Content Credentials into the images it captures. You can interact with the inspector using the source links. Self-signed credentials (source) Credentials baked into an image at time of capture (source) If you're paying attention, it's easy to spot the differences. But if you've only seen the first one, the UI doesn't make it clear at all that there's no information on how the image was made. Was it generated with an AI that doesn't apply a watermark or add credentials of its own? Did a human artist spend painstaking hours putting it together? The tool has no idea, but the badge would look the same either way. Now imagine it wasn't an illustration but a photorealistic image. While the UI doesn't show all the details that it does for a photo that's had credentials since the shutter was taken, it's also not really clear that those are missing. Visually, the tool gives as much credence to a picture that's as verifiably real as it can be as it does to an image that could've come from anywhere. There's nothing that says the only thing someone's done is upload a JPG or PNG to the tool It's also a problem of language. If you're inspecting a self-signed image, there's nothing that tells you that the only thing someone's done is upload a JPG or PNG to the tool and check a box to promise that they're the one who owns it. It uses squishy language like "information shared by people involved in making this content" because it has to; there's no way to verify that, not that you'd get that impression if you weren't reading it with a cynical eye. The inspection part of the tool can show what changes were made to an image, provided that information is included in the Content Credentials.Screenshot: Mitchell Clark The worst part is that there are good bones here. While only a handful of cameras generate Content Credentials at time of capture*, tools like Photoshop and Adobe Camera Raw can add metadata of their own, building something akin to a chain of custody. The inspector can show what edits you've applied to an image if you've used Adobe's AI tools at any point and even show if you've composited multiple images together. It should be crystal clear at a glance that images with those credentials are more trustworthy than self-signed ones. * - And of those, the majority lock the feature behind a license only given out to news agencies and other commercial operations It is worth noting that Adobe is only one piece of the puzzle – other software developers can implement support for inspecting Content Credentials and make the difference between the types of credentials clearer. Maybe there could be a color-coding system to differentiate credentials that came from a camera versus ones from editing software and tools like Adobe Content Authenticity. Also, none of this is to say that the self-signing process shouldn't exist because there are good reasons to use it. For example, suppose you have an image with that chain of credentials we talked about. You could use the Adobe Content Authenticity app to watermark it and link it to your socials so you get credit for it; the tool is smart enough to add things on top of existing Content Credentials. Illustrators could also use it to slightly raise the chances that their work will get credited. Adobe Content Authenticity also lets you add a tag requesting that companies not use your image when building their Generative AI models. While many people would like a way to keep their work from contributing to AI tools, it's worth noting this isn't a silver bullet. Adobe's suppor

|

| Image: Adobe |

Last week, Adobe announced that it's opening up the beta for its Content Authenticity app, which launched in private beta last year. This means more people will be able to access the tool's features, which let you add secure metadata to an image claiming that you own it and add a flag asking AI companies not to use it to train their models.

That should be a good thing. But the current implementation could threaten to muddy the waters about what images are authentic and what aren't even further, which is the exact problem the tool was made to solve.

If you're not familiar with the Adobe Content Authenticity app (and don't want to read the in-depth piece we wrote about it when it was launched), here's a quick summary: it's built around the Coalition for Content Provenance and Authenticity (C2PA) Content Credentials system. It lets you add a cryptographically signed piece of metadata that says you made the image. It can also link to social profiles on sites like Instagram, Behance, and, now, LinkedIn. A link to that metadata is also added as an invisible watermark into the image, so it should be retrievable even if someone screenshots it or strips its metadata.

Let's do a quick compare and contrast, though. On the left is what those self-signed credentials look like when viewed in Adobe's inspector, and on the right is what they look like when they come from a camera that bakes Content Credentials into the images it captures. You can interact with the inspector using the source links.

|

|

| Self-signed credentials (source) | Credentials baked into an image at time of capture (source) |

If you're paying attention, it's easy to spot the differences. But if you've only seen the first one, the UI doesn't make it clear at all that there's no information on how the image was made. Was it generated with an AI that doesn't apply a watermark or add credentials of its own? Did a human artist spend painstaking hours putting it together? The tool has no idea, but the badge would look the same either way.

Now imagine it wasn't an illustration but a photorealistic image. While the UI doesn't show all the details that it does for a photo that's had credentials since the shutter was taken, it's also not really clear that those are missing. Visually, the tool gives as much credence to a picture that's as verifiably real as it can be as it does to an image that could've come from anywhere.

There's nothing that says the only thing someone's done is upload a JPG or PNG to the tool

It's also a problem of language. If you're inspecting a self-signed image, there's nothing that tells you that the only thing someone's done is upload a JPG or PNG to the tool and check a box to promise that they're the one who owns it. It uses squishy language like "information shared by people involved in making this content" because it has to; there's no way to verify that, not that you'd get that impression if you weren't reading it with a cynical eye.

|

|

The inspection part of the tool can show what changes were made to an image, provided that information is included in the Content Credentials. |

The worst part is that there are good bones here. While only a handful of cameras generate Content Credentials at time of capture*, tools like Photoshop and Adobe Camera Raw can add metadata of their own, building something akin to a chain of custody. The inspector can show what edits you've applied to an image if you've used Adobe's AI tools at any point and even show if you've composited multiple images together. It should be crystal clear at a glance that images with those credentials are more trustworthy than self-signed ones.

* - And of those, the majority lock the feature behind a license only given out to news agencies and other commercial operations

It is worth noting that Adobe is only one piece of the puzzle – other software developers can implement support for inspecting Content Credentials and make the difference between the types of credentials clearer. Maybe there could be a color-coding system to differentiate credentials that came from a camera versus ones from editing software and tools like Adobe Content Authenticity.

Also, none of this is to say that the self-signing process shouldn't exist because there are good reasons to use it. For example, suppose you have an image with that chain of credentials we talked about. You could use the Adobe Content Authenticity app to watermark it and link it to your socials so you get credit for it; the tool is smart enough to add things on top of existing Content Credentials. Illustrators could also use it to slightly raise the chances that their work will get credited.

Adobe Content Authenticity also lets you add a tag requesting that companies not use your image when building their Generative AI models. While many people would like a way to keep their work from contributing to AI tools, it's worth noting this isn't a silver bullet. Adobe's support documentation explicitly calls the flag a "request," and the legal framework around AI training is still in flux, so few enforcement mechanisms around opt-out requests like this exist.

|

| Screenshot: Adobe |

In a blog post, Adobe says it's "working closely with policymakers and industry partners to establish effective, creator-friendly opt-out mechanisms powered by Content Credentials." However, it appears to be early days. The company's documentation says the preference is currently respected by its in-house AI image generator, FireFly, and that a company called Spawning is working on supporting it. Spawning runs what it calls a "Do Not Train registry," which – in theory – lets you submit your work to a single place, which will let several companies know that you don't want it used for their training. Spawning's site currently says that Hugging Face and Stability AI (creators of Stable Diffusion) have "agreed to honor the Do Not Train registry."

It's unclear whether other companies like Google or MidJourney have or are building mechanisms to respect preferences like the ones embedded in Content Credentials. When we asked OpenAI, we were told nothing to share at this time. We've also reached out to Google and MidJourney and will update this article if we hear back.

While it's clear that I think there's work to be done on this app, it does seem like Adobe is willing to improve it. The public beta comes with new features, such as the ability to bulk-add credentials and preferences to up to 50 JPGs or PNGs at a time. Adobe says it'll soon support larger files and more file types and that it's working on integrating the app into programs like Photoshop and Lightroom. Again, though, that's arguably only useful if the inspection tool makes it clear how much stock you should put in those generated credentials or if AI companies writ large start respecting your do-not-train preferences.

You can join the waitlist for the Adobe Content Authenticity beta for free on the company's website. It requires an Adobe account but not a Creative Cloud subscription and works with any JPGs and PNGs, not just ones produced by Adobe apps.

Read our interview with Adobe's senior Content Authenticity Initiative director

![The History of the Universal Monsters: How ‘The Invisible Man’ Nearly Vanished Into Hollywood Limbo [Halloweenies Podcast]](https://bloody-disgusting.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/the-invisible-man-halloweenies.jpeg)

![[Dead] Japan Airlines First Class wide open through JetBlue TrueBlue (though it’s expensive)](https://frequentmiler.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/11/JAL-first-seat.jpg?#)

![Marriott Is Now Advertising Hotels In North Korea [Roundup]](https://viewfromthewing.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/ChatGPT-Image-Apr-27-2025-04_25_59-AM.jpg?#)