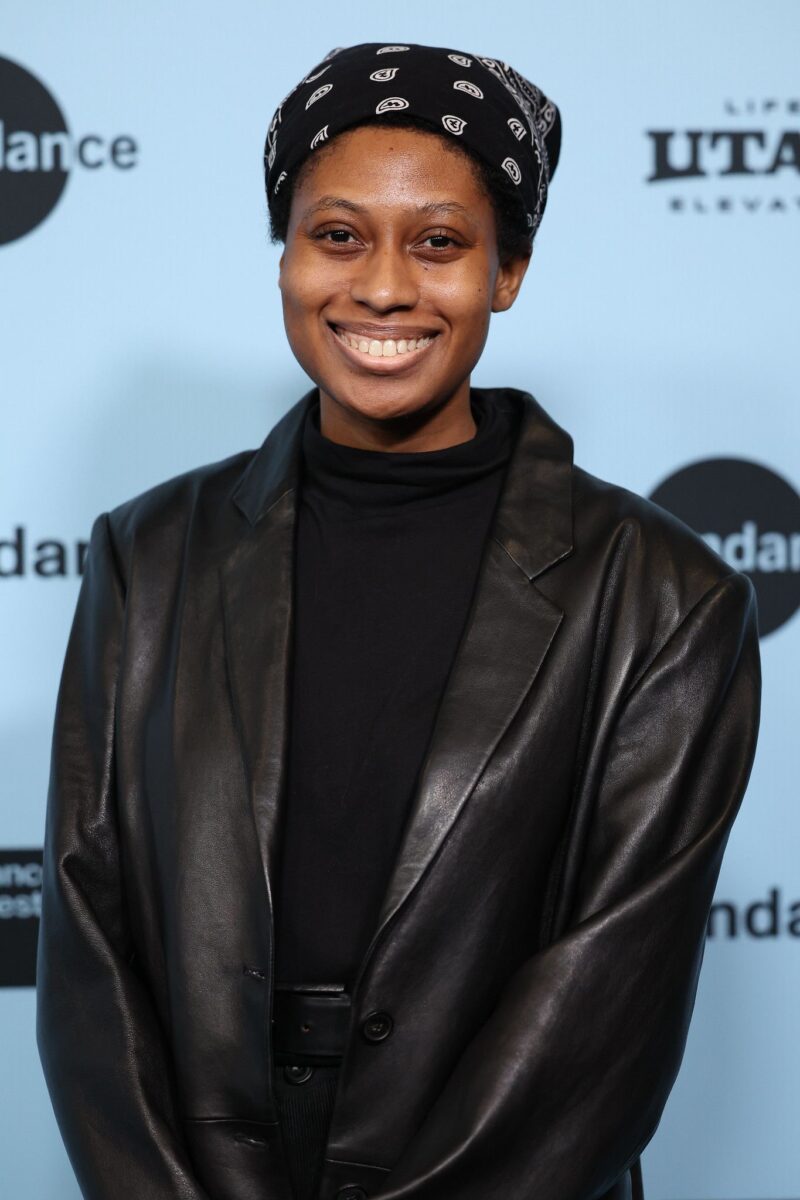

“There Are So Many Black Stories That Are Not Duly Explored”: Seeds Director Brittany Shyne on Her Sundance-Winning Debut

Director Brittany Shyne didn’t grow up on a farm, but a family history rooted in agrarian work inspired her to make a film about Black land ownership and generational farmers in the American South. Shyne started working on the project that became Seeds, which won best documentary at Sundance this year, while still at grad […] The post “There Are So Many Black Stories That Are Not Duly Explored”: Seeds Director Brittany Shyne on Her Sundance-Winning Debut first appeared on The Film Stage.

Director Brittany Shyne didn’t grow up on a farm, but a family history rooted in agrarian work inspired her to make a film about Black land ownership and generational farmers in the American South. Shyne started working on the project that became Seeds, which won best documentary at Sundance this year, while still at grad school in Northwestern: an MFA thesis subject that she eventually documented for over nine years and 400 hours of film.

The result is an unusually intimate portrayal of contemporary agricultural life focusing primarily on the Williams family, who have owned their land since 1883, and Willie Head Jr., who is both a great grandfather who wishes for his family to remain on the land and an activist who fights the USDA for bank loans for Black farmers. While referencing these broader socio-political themes, Shyne keeps her film’s focus beguilingly intimate, lingering on familial bonds and evoking a gulf of history.

We met earlier this year at the Thessaloniki Documentary Festival, where Seeds just had its international premiere and Shyne fielded questions at a post-midnight Q&A. We connected the following morning, taking a seat outside to enjoy the morning sunshine and discuss family history and the artists who inspired her. Ahead of the film’s NYC premiere this Friday at the 2025 Margaret Mead Film Festival, enjoy the conversation below.

The Film Stage: Congratulations on the prize at Sundance. How was that experience for you, as a first-time filmmaker?

Brittany Shyne: It was great. Intense. A whirlwind. But also very gratifying, to be able to finally release it out into the world.

How did you approach Willie Head Jr. with the film? What was that first meeting like?

His story came on a lot later than the Williams family, which is the oldest farming family in the film. With some of the family members passing away, the story was changing and I knew I needed something else. I found an article about Willie, about him being an activist––a very small article, but there was something very compelling, even in that short little segment. So I reached out to him in ’21, because he lived, like, 25 minutes away from the Williams family. I just drove out there when I was already in Thomasville. He was very open about me doing a film because he’d spoken to journalists before––even though I’m not a journalist, but he kind of understood what I was going to do.

He wanted his story to be told.

He did, he wanted his story to be told. And he’s been an amazing collaborator on this film.

He brings so much to it. The fact that the film doesn’t use any text or anything, and still there is so much information in there from how Willie talks about the situation.

That, for me, was very important. I never wanted the film to feel didactic or formulaic; I really wanted us to understand this space, these different farmers’ lives, and the everyday. It’s amazing because Willie has so much knowledge and so much history, but also he’s able to provide the background context without doing any kind of formal interviews, which is lovely.

So this more overtly political side to Seeds came a lot later in the filming?

With Willie’s storyline, absolutely, just with him being an activist but also his connection with other Black farmers in the area. That was one of the last big shoots I had, in 2023, when they went up to the White House. It was one of those things. It’s an important moment in the film, but I didn’t go into that thinking, “Oh, we’re gonna have this element.” It was just something that naturally flowed through his storyline, that we see kind of evolve as they’re fighting for the USDA settlement.

Was it tempting to make that the central arc of the film? I think another filmmaker might have ended with it, the Big Trip to Washington. You know?

Totally, but I think it’s just another chapter of their lives. As I said last night: they’ve been fighting this fight for 30 years. It’s been a huge struggle, but for me the arc of the film wasn’t all these political strifes; it’s what they were trying to maintain in the everyday. To me, this film was about maintenance of legacy, and I think that it’s important to show Black farmers in their full arc, their full humanity, and not just, like, this plight or struggle; there’s a lot of love and tenderness embedded through this film. That was the foundation for me, what I really wanted to highlight, throughout the story.

And with the Williams family, how did you approach them first? Was there a connection there?

Actually it was my mother, because she knew I wanted to do a film about Black farmers, so she found an article about the Williams family online. So we spoke to the matriarch of the family, Belle, and even though she’s not a farmer, she grew up on the land. So we got in contact with her and I was able to go down to Thomasville because Belle invited me. That was my initial intro to their lives.

Are the earlier scenes in the film some of the first you shot? The intimacy and the closeness there, especially in the back seat of the car, is remarkable.

No, the funeral happened a few years in. But stuff like the eyeglasses was really early on in the film. The trip to the optometrist. Some of the cotton scenes.

The intimacy in that moment was startling. Was it important for you to kind of lay down a marker early on for the audience, that there is going to be this kind of closeness?

Yes, and I think cars are a huge motif throughout the film. I knew that we’re gonna have a lot of car scenes. And to start with a funeral. My film is very cyclical and non-linear––it’s about the passage of time, about how these elder members are kind of dwindling away. It felt like it would help us to understand the elements that are kind of percolating in the background. Who’s gonna take over this land? Who’s gonna continue this generation of farmers? So I really wanted to settle us in these car scenes that are intimate but also reflective of the community as well. I liked that scene, too, because Claire is talking to Ebery, who is her grandniece. It’s important to see that she is starting to understand these family dynamics as well and understanding what death means, you know?

It’s beautiful to think of this younger generation watching it in 10, 15 years’ time. Is that something you thought about while making it?

I mean, in some ways, but you really don’t know. [Laughs] You think about a lot of things when you’re making a film and you don’t really know how it’s gonna resonate 20 years from now. I knew it was important to document their stories because there’s something so special but something so fragile happening at the same time. And, for me, it was necessary to understand my ancestral knowledge in ways that I can’t. Because I didn’t grow up on a farm, but I knew that there are others who are continuing this legacy.

The idea to shoot in black-and-white, was that also tied into that archival sense, to give it a kind of timeless quality?

That’s definitely connected. I knew the passage of time was going to be a theme in my film, and also people think of farming life as vibrant and beautiful. I feel it’s still that way in black-and-white, but for me the center of these stories were the elders, the people in the film, and I really wanted to linger in their time space. You know, things are slowing down, but not just age-wise––also how they live their lives. Things are much more sedentary, and I really wanted to hone in on these long days and these moments were you’re just with them in the quotidian, you’re really lingering in this communal space.

In bell hooks’ book Belonging, she talks about growing up in Kentucky and how the porch space was a communal space, and to me that’s how the farm space was. You had these spontaneous encounters where people were just hanging out. But the space is in their cars, right? I think black-and-white allows me to suspend and linger in a way that I felt like I could do.

For me, the most intimate moment in the film is this scene where you help to wash Claire’s hair––it’s such a beautiful moment. I was just curious if you were conflicted at all about leaving it in? It’s the only time we hear your voice and you almost enter the frame.

I mean, the fourth wall is breaking throughout the film. [Laughs] It’s something that I felt was always there. Like, older people: they don’t really care. They’re aware of the camera, they’re aware of my presence, but they’re like, “Do you want candy?” Or whatever. So I felt like it was just a natural thing. And I felt that was a hugely symbolic moment for all the other moments. To me, it’s one of those special scenes in the film just because it connects me to their family, but in a way that’s different because she’s articulating my connection with her husband as well, who passed away.

You’ve spoken about it as a work of “portraiture.” How do you approach that in a practical way? Do you set some kind of guidelines aesthetically or in terms of filming?

I mean, it’s a first feature, so you’re kind of just working on instincts in some way. You’re filming for long days or for long periods of time. For me, thematically, the most significant moments would be minuscule; it’s not going to be the grand moments that we might perceive in a film. I really wanted to highlight those moments that are sometimes forgotten or not duly explored. It was a juxtaposition of their lives in a way that was building a tapestry of who they are as people, of what it means to be a farmer in this agricultural landscape, what does it mean to be tethered to a place.

It’s been a long film, so a lot of things evolved. I expanded the project to include other farmers, and that changed the way I filmed, because when I’m with the elders I’m on sticks a lot, whereas with Willie I was handheld a lot. So you’re constantly evolving or being malleable to changes that are occurring.

It’s visually consistent for something that you shot for such a long period of time. Did you have any visual references? I saw Gordon Parks referenced in my colleague’s review.

I mean, there’s a lot of prolific photographers, filmmakers––like Charles Burnett, Roy DeCarava, P.H. Polk, the Mexican photographer Graciela Iturbide. There was just a lot of people who influenced me in some way to make this film.

Were there particular filmmakers who got you into filmmaking?

Yeah, but no. Those influences came through my time in school, really. I think as a younger person I was always into the arts, I was a voracious reader, I would always be watching movies at home throughout the day. Like the Sundance Channel, IFC, anything really. I just really liked storytelling and I felt like the visual arts was a medium I really wanted to explore. I knew that since high school. I felt like there are so many Black stories that are not duly explored, that remain invisible. It’s important to highlight them in ways we haven’t seen.

I definitely hadn’t seen this community represented in a film before. I presume you’re still in touch with some of the people you filmed. I was curious how they’re holding up. We see Willie on this call with the Farm Service Agency, fighting for these USDA loans. Is the situation with Trump and DEI affecting this in a direct way already?

I talked to Willie recently. Not because of that, though. I think there has been a lot of setbacks just because of the Trump administration––there’s a lot of things that are being rescinded––and we don’t really know what’s gonna happen in the foreseeable. I mean, we kind of know. It’s not good, but it’s not something that… [Sighs]

It’s still going to be a struggle, just in a different way. This is a familiar fight.

They’ve seen it all before.

Yeah, it just changes hands.

Seeds makes its NY premiere this Friday, May 2 at the 2025 Margaret Mead Film Festival.

The post “There Are So Many Black Stories That Are Not Duly Explored”: Seeds Director Brittany Shyne on Her Sundance-Winning Debut first appeared on The Film Stage.

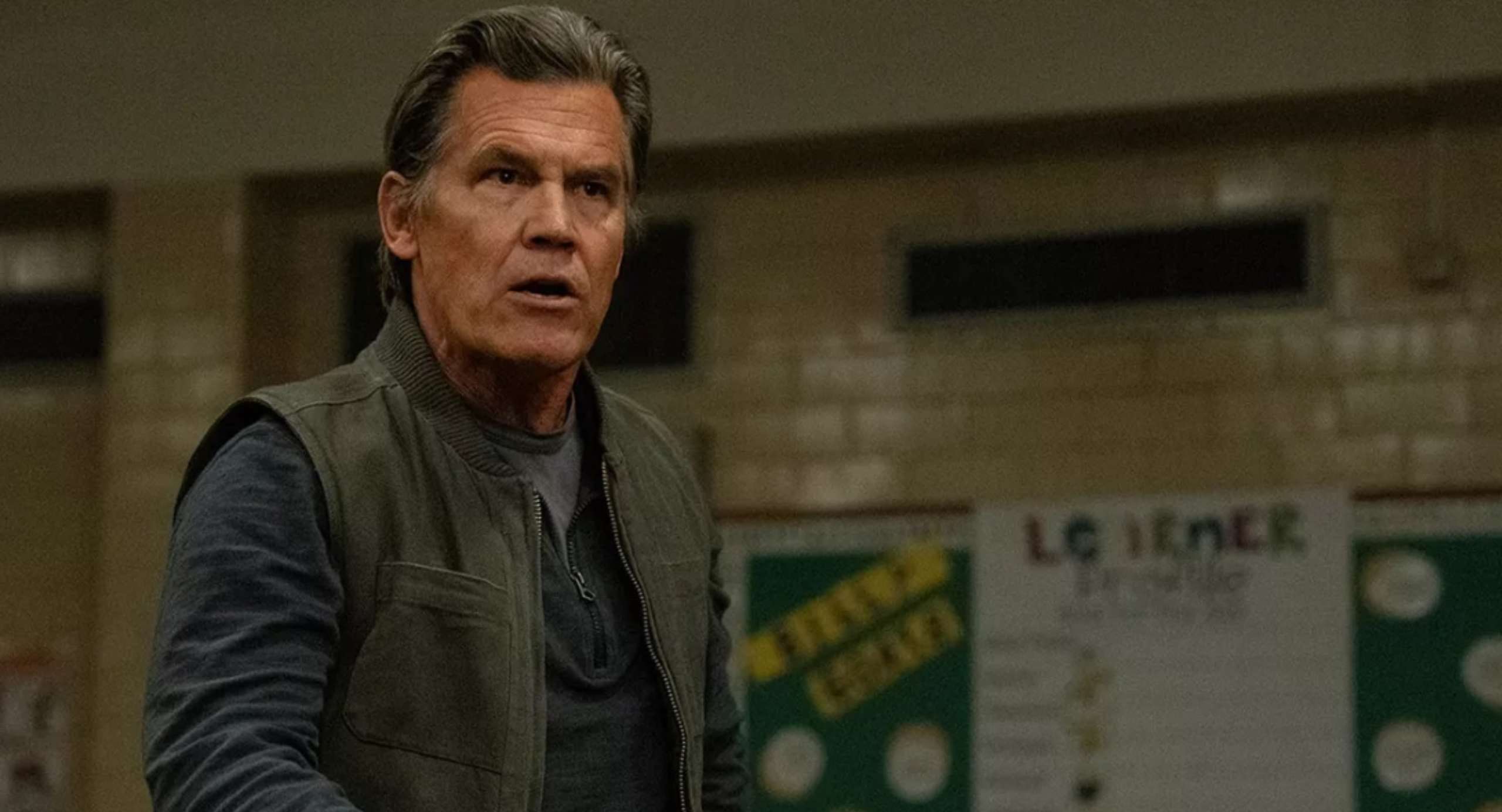

![‘Project MKHEXE’ Clip Uncovers a Mysterious Treehouse [Exclusive]](https://bloody-disgusting.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/MKHEXE_still.jpg)

![Kyoto Hotel Refuses To Check In Israeli Tourist Without ‘War Crimes Declaration’ [Roundup]](https://viewfromthewing.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/war-crimes-declaration.jpeg?#)

.png?width=1920&height=1920&fit=bounds&quality=70&format=jpg&auto=webp#)

.jpg?#)