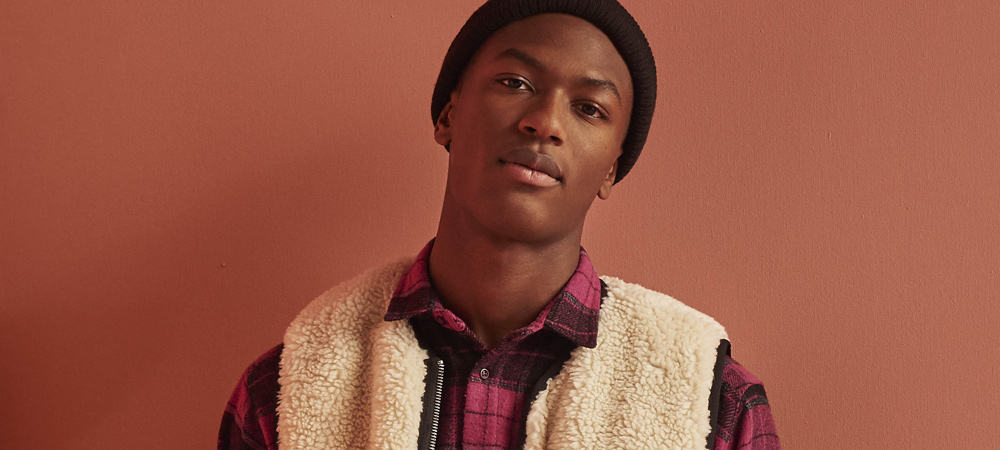

The quiet intensity of Lee Kang Sheng’s gaze

Through his collaborations with Tsai Ming Liang and new work with Constance Tsang and Yeo Siew Hua, Lee Kang Sheng has created a remarkable body of work. The post The quiet intensity of Lee Kang Sheng’s gaze appeared first on Little White Lies.

Our first glimpse of Lee Kang Sheng in Tsai Ming Liang’s Rebels of the Neon God (1992) features the young man seated at a desk. His back is turned to the camera while his leg jitters in boredom. When he spies a cockroach skittering across the floor, he coldly stabs it with a compass and nails its writhing body to the desk. This act of juvenile cruelty appears to reveal something about Hsiao-Kang, the laconic drifter that Lee would reprise as Tsai’s long-time leading man – as an amateur actor in The River (1997), a watch salesman in What Time Is It There? (2001), a pornstar in The Wayward Cloud (2005), an alcoholic father in Stray Dogs (2013), and a middle-aged man with chronic neck pain in Days (2020). But in Lee’s three decades as Hsaio-Kang, the character remains as elusive to viewers as when he was first introduced. It’s unclear whether a narrative links together these various iterations of Hsiao-Kang. Rather, it is Lee’s familiar presence that has taken on significance, anchoring us in time across Tsai’s minimalist filmography.

It’s impossible to consider Lee’s work as an actor without mentioning Tsai – an auteur whose work stands in stark opposition to industry norms. Tsai’s films contain little dialogue and action. They are quotidian studies of people’s lives, revolving around a small ensemble cast. Lee has starred in everything the director has made, from telefilms to shorts to art installations, since the two met in an arcade in 1991. Their collaboration remains indispensable to Tsai, who’s confessed that he wouldn’t want to make films without Lee’s participation. Indeed, the affective intensity – and familiarity – of Lee’s performance imbues Tsai’s work with its durational gravitas. “Lee’s whole essence goes against all the standards set by society, especially those of the acting profession, and against preexisting notions of performance,” Tsai remarked in a 2015 interview.

Lee is simultaneously unassuming and striking, such that it’s difficult to discern whether he’s acting or simply being. His presence transcends any fixed sense of character, even when, as a monk in the Walker (2012) series, he’s clearly playing a role. But unlike a movie star, who seizes our attention by the sheer force of their celebrity, Lee’s on-screen purpose is more like a mediator, attuning us to the slow, deliberate pace of Tsai’s cinema. Days (2020) opens with Lee sitting silently, staring out at the rain. In this tranced repose, the actor’s gaze is soft and unblinking, as if he is on the verge of drifting off into sleep. But one minute into this five-minute scene, Lee’s eyes suddenly dart sideways, jolting the viewer’s attention in the direction of his focus. This is the subtle power of Lee’s gaze. Though never confrontational, it holds the viewer in suspense. There is a unique symbiosis to Lee’s and Tsai’s collaborations, but I find that Lee’s extratemporal essence – a quality that makes him “the world’s most anarchistic person,” according to Tsai – becomes most apparent in his later work with directors who command a faster narrative pace.

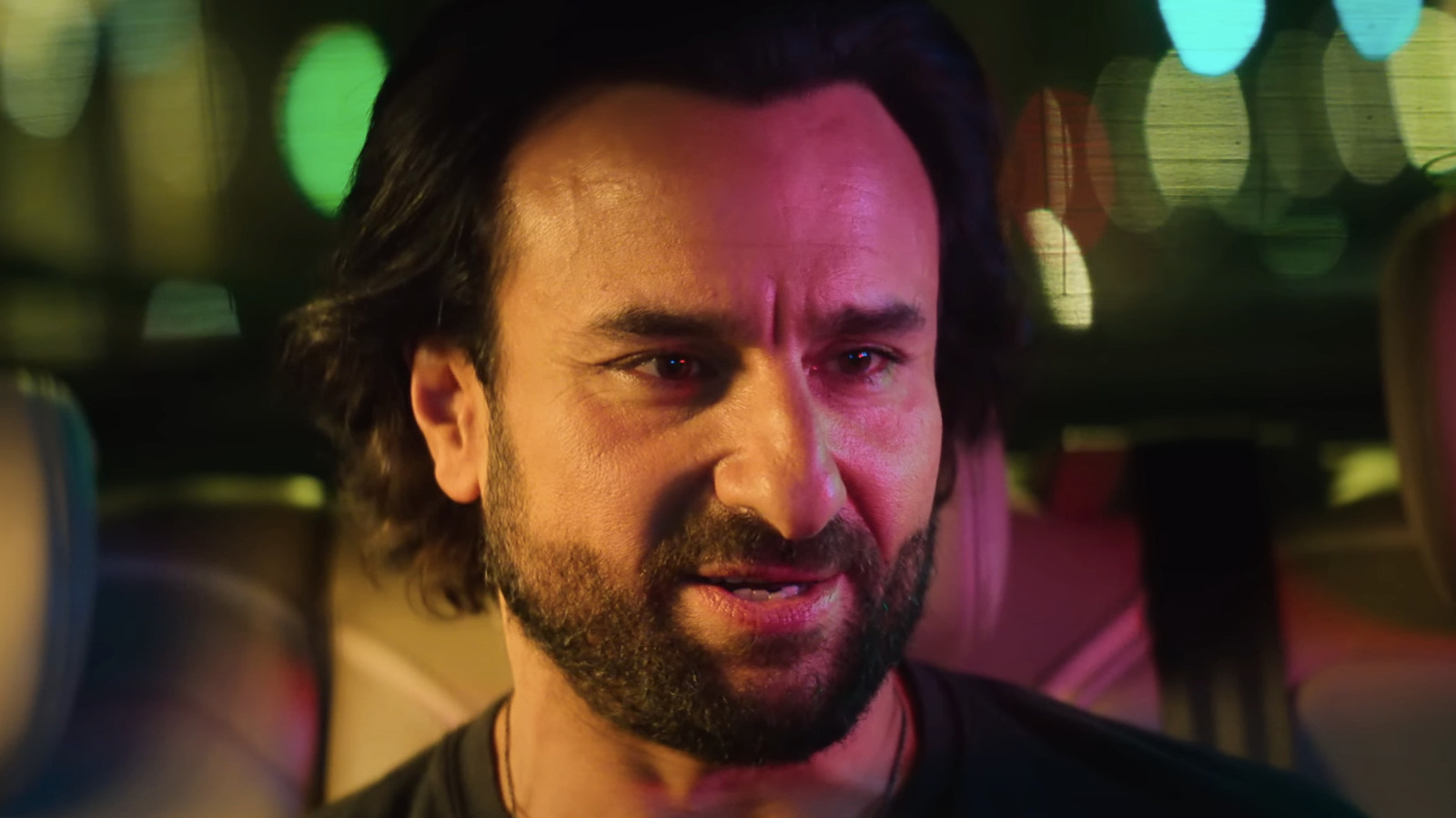

In Yeo Siew Hua’s thriller Stranger Eyes (2024), Lee is introduced as a stalking voyeur surreptitiously recording his neighbors’ daily routines. Police attention turns on Lee’s Lao Wu after a baby disappears in broad daylight. There is a frightening menace to Wu’s affect that becomes diminished once the film shifts perspective, as his character’s motivations are revealed. Lee might have the least amount of lines compared to his co-stars, but his performance bolsters Stranger Eyes’ preoccupation with the ubiquity of digital surveillance. In one scene, Wu sits before a large screen to survey footage, marveling at the intimacies his camera is privy to. Here, Lee’s eyes hold us in the act of spectating, as we spy alongside him. As Wu, he functions as an observant mediator, unsettling the viewer’s gaze to the different ways we see and are seen by others. It’s why, even in his most defining roles, Lee rarely needs to speak. The heft of his performances as Hsaio-Kang is found in slight gestures and unmet glances. Lee’s reticence in Stranger Eyes only furthers Wu’s enigma, heightening the tension by leaving his character’s motives up to interpretation.

Lee’s latest role in Constance Tsang’s Blue Sun Palace (2025) chips away at this subdued inscrutability, presenting him with a refreshing range of emotions. As Cheung, a middle-aged construction worker involved in an affair with Didi (Haipeng Xu), a massage parlor worker, we meet him as a shyly earnest lover on a date at a restaurant in Queens. Lee’s Cheung is tender in his interactions, seemingly astonished in his infatuation with the playful Didi. After dinner, the two go to karaoke and Didi invites Cheung to sleep over at the parlor, where she lives and works. Their easygoing romance is short-lived, however, after Didi is murdered in an armed robbery on New Year’s. Her death ruptures the trajectory of the film and the characters’ lives; the tragedy cleaves the film into two. It’s in this latter half – where the camera and characters move slowly, weighed down by grief – that the subtleties of Lee’s performance shine. Grief can render a person out of time, and Lee, with his uniquely slow “acting rhythm,” embodies Cheung’s inner conflict.

Cheung tries to hide his sorrow from friends and coworkers but the facade inevitably slips. There’s a visible change in his posture and affect. His eyes lose their brightness. He appears to move slower. Yet we never witness a moment of catharsis or breakdown. Instead, Lee reveals the character’s suffering in small doses. After Cheung hangs up on a video call from his wife in Taiwan, who frequently nags him for more money, his face crumples in anguish. And when he finally sleeps with a new woman, he slaps himself in self-punishment. Blue Sun Palace is not without moments of genuine joy, sparked by Cheung’s newfound connection with Amy, Didi’s friend and business partner. The two bond over their shared loss by eating together and going to karaoke. But it becomes clear that Cheung is trying to recreate his romance with Didi, as his expressions never quite reach the level of exuberance that we saw at the film’s start. Nevertheless, it’s satisfying to witness such an effusive showcase from an actor known for his restraint.

The poignancy of Lee’s performance arises from the tension between moving on and staying put at the site of loss – an unresolved struggle for Cheung. The film’s final shot is a close-up of Lee/Cheung, smoking and staring out at the beach that Didi had wanted to visit with him. Lee continues to smoke as the credits roll. The five-minute scene is a study of Lee’s contemplative face, as the viewer is left to parse the nuances of his expression. Is Cheung thinking of Didi? What exactly is he reminiscing about? These questions remain unanswered as Lee looks on. Tsang offers us Lee’s silent gaze as its own kind of answer, tethering us to the ambiguity of the moment before the screen fades to black.

The post The quiet intensity of Lee Kang Sheng’s gaze appeared first on Little White Lies.

![Check Into Shudder’s ‘Hell Motel’ from the Creators of ‘Slasher’ [Trailer]](https://i0.wp.com/bloody-disgusting.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/hellmotel-still.jpg?fit=1280%2C720&ssl=1)

![Marvel Preview: A Deadpool And Wolverine Villain Gets Her Own Team In X-Men #16 [Exclusive]](https://www.slashfilm.com/img/gallery/marvel-preview-a-deadpool-and-wolverine-villain-gets-her-own-team-in-x-men-16-exclusive/l-intro-1746064020.jpg?#)

![Southwest’s Free Wi-Fi Trial Could Backfire—Here’s Why [Roundup]](https://viewfromthewing.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/southwest-airlines-jet.jpeg?#)