After Catastrophe: The Video Art of François Pain

A version of this essay appears in Everybody Wants to Be a Fascist: Institutional Psychotherapy as a Resistance Movement by François Pain, edited by Perwana Nazif, published by Semiotext(e) on the occasion of François Pain, Psychiatry Is What Psychiatrists Do at JOAN, Los Angeles, February 21 through May 17, 2025.Installation view of François Pain, Psychiatry Is What Psychiatrists Do at JOAN, Los Angeles, February 21 through May 17, 2025. Photograph by Evan Walsh. Image courtesy of the artist and JOAN.How to begin with catastrophe? This is the question that frames François Pain’s new video installation, Institutional Psychotherapy as One of the Fine Arts… (2025), in the exhibition that accompanies this publication. From 1965 to 1972, before he became one of the first video artists in France, François Pain worked at La Borde, the famed clinic in France’s Loire Valley that extended the practices of institutional psychotherapy established at Saint-Alban Hospital in the south. At La Borde, Pain met and established significant relationships with the major representatives of institutional psychotherapy: exiled Catalan militant and IP founding figure Francesc Tosquelles, who became Pain’s analyst; La Borde’s founder, Jean Oury; and Félix Guattari, a core staff member who became Pain’s close friend. The triangulation of these three thinker-practitioners, whom Pain later referred to as “TOG,” offered a conceptual and practical foundation for Pain. Each point of the triangulation finds distinct and collective expression in Pain’s chronicles of institutional psychotherapy at experimental clinics, and his films have played a crucial role in the movement’scirculation and extensions.Institutional psychotherapy emerged in Saint-Alban during the Second World War, as the German occupation and the Vichy government’s “soft extermination” policies produced a fatal dearth of adequate clinical care and physical sustenance for French patients in psychiatric institutions. A cultural revolution and antifascist resistance movement that aimed to cure the hospital itself, institutional psychotherapy was a horizontal, collective effort traversing political, libidinal, and subjective economies. Informed by Tosquelles’s experiences in Catalan workers’ cooperatives, his antifascist militancy, and a therapeutic-communal foundation put in place by previous directors, Saint-Alban did not assume itself to be an asylum; instead, it worked toward becoming a refuge, endlessly subject to transformation. Persistent intervention and creative transformation aimed to keep desire circulating, parallel to the relationship between patient and analyst and beyond fascism’s existing political and social reality. At Saint-Alban, the so-called “mad” and “normal” lived together among resistance fighters, artist-poet refugees, and dissidents of the state. Patients and non-clinical staff alike took responsibility for unbinding the hospital, breaking down its walls and freeing its occupants to move without restriction. Patients worked for and bartered with staff and villagers from the surrounding area, and those neighbors were invited to celebrations and performances at the hospital. This strategy made possible the approach of a care collective, in which traditional clinical hierarchies, taxonomies, and nosologies retreated. A consideration of sociality’s force redirects its course toward patients’ autonomy, and the rights to wander and to exchange flow forth. Such was a fluid and liberated circulation with structure—a collective facilitation of movement within and beyond the walls of the hospital by foot and by expression. Installation view of François Pain, Psychiatry Is What Psychiatrists Do at JOAN, Los Angeles, February 21 through May 17, 2025. Photograph by Evan Walsh. Image courtesy of the artist and JOAN.Psychiatry is what psychiatrists do, as the exhibition’s title notes, but psychiatrists do not stand outside the social, historical and material world, nor what the patient suffers.1 Institutional psychotherapy’s existential practices emphasize again and again that the mental and somatic was not isolated from the structural and historical, inclusive of fantasy. A permanent reconstruction and an unceasing revolution, institutional psychotherapy is a line of escape from fixed constructions, relations, and milieus, a vector that must be endlessly (re)imagined and actualized.2If institutional psychotherapy collapsed the hospital’s walls, it stands to reason that its practices and insights could not be contained at La Borde. While Oury’s medical and analytic work focused on the local economy, Guattari’s political commitments—to the Algerian struggle, workers’ movements, and other social fields—extended the presence of the hospital to the world beyond. The supposed presence of police around the clinic may or may not have had to do with the suitcases of cash for the FLN (The National Liberation Front for Algerian Liberation) which were rumored to be passing thr

A version of this essay appears in Everybody Wants to Be a Fascist: Institutional Psychotherapy as a Resistance Movement by François Pain, edited by Perwana Nazif, published by Semiotext(e) on the occasion of François Pain, Psychiatry Is What Psychiatrists Do at JOAN, Los Angeles, February 21 through May 17, 2025.

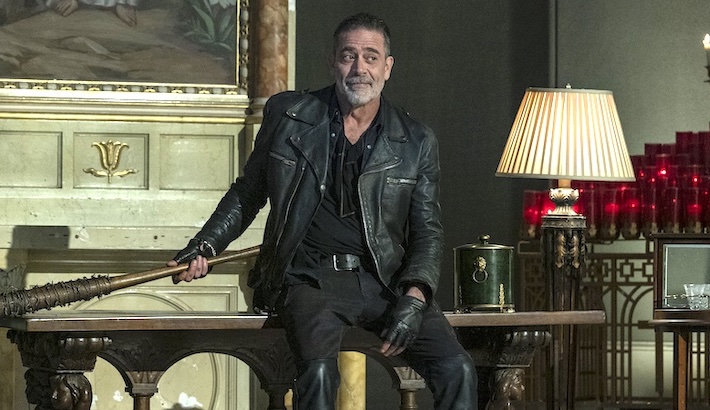

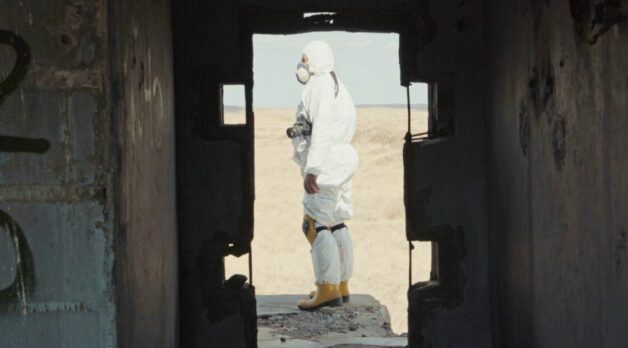

Installation view of François Pain, Psychiatry Is What Psychiatrists Do at JOAN, Los Angeles, February 21 through May 17, 2025. Photograph by Evan Walsh. Image courtesy of the artist and JOAN.

How to begin with catastrophe? This is the question that frames François Pain’s new video installation, Institutional Psychotherapy as One of the Fine Arts… (2025), in the exhibition that accompanies this publication.

From 1965 to 1972, before he became one of the first video artists in France, François Pain worked at La Borde, the famed clinic in France’s Loire Valley that extended the practices of institutional psychotherapy established at Saint-Alban Hospital in the south. At La Borde, Pain met and established significant relationships with the major representatives of institutional psychotherapy: exiled Catalan militant and IP founding figure Francesc Tosquelles, who became Pain’s analyst; La Borde’s founder, Jean Oury; and Félix Guattari, a core staff member who became Pain’s close friend. The triangulation of these three thinker-practitioners, whom Pain later referred to as “TOG,” offered a conceptual and practical foundation for Pain. Each point of the triangulation finds distinct and collective expression in Pain’s chronicles of institutional psychotherapy at experimental clinics, and his films have played a crucial role in the movement’scirculation and extensions.

Institutional psychotherapy emerged in Saint-Alban during the Second World War, as the German occupation and the Vichy government’s “soft extermination” policies produced a fatal dearth of adequate clinical care and physical sustenance for French patients in psychiatric institutions. A cultural revolution and antifascist resistance movement that aimed to cure the hospital itself, institutional psychotherapy was a horizontal, collective effort traversing political, libidinal, and subjective economies. Informed by Tosquelles’s experiences in Catalan workers’ cooperatives, his antifascist militancy, and a therapeutic-communal foundation put in place by previous directors, Saint-Alban did not assume itself to be an asylum; instead, it worked toward becoming a refuge, endlessly subject to transformation. Persistent intervention and creative transformation aimed to keep desire circulating, parallel to the relationship between patient and analyst and beyond fascism’s existing political and social reality.

At Saint-Alban, the so-called “mad” and “normal” lived together among resistance fighters, artist-poet refugees, and dissidents of the state. Patients and non-clinical staff alike took responsibility for unbinding the hospital, breaking down its walls and freeing its occupants to move without restriction. Patients worked for and bartered with staff and villagers from the surrounding area, and those neighbors were invited to celebrations and performances at the hospital. This strategy made possible the approach of a care collective, in which traditional clinical hierarchies, taxonomies, and nosologies retreated. A consideration of sociality’s force redirects its course toward patients’ autonomy, and the rights to wander and to exchange flow forth. Such was a fluid and liberated circulation with structure—a collective facilitation of movement within and beyond the walls of the hospital by foot and by expression.

Installation view of François Pain, Psychiatry Is What Psychiatrists Do at JOAN, Los Angeles, February 21 through May 17, 2025. Photograph by Evan Walsh. Image courtesy of the artist and JOAN.

Psychiatry is what psychiatrists do, as the exhibition’s title notes, but psychiatrists do not stand outside the social, historical and material world, nor what the patient suffers.1 Institutional psychotherapy’s existential practices emphasize again and again that the mental and somatic was not isolated from the structural and historical, inclusive of fantasy. A permanent reconstruction and an unceasing revolution, institutional psychotherapy is a line of escape from fixed constructions, relations, and milieus, a vector that must be endlessly (re)imagined and actualized.2

If institutional psychotherapy collapsed the hospital’s walls, it stands to reason that its practices and insights could not be contained at La Borde. While Oury’s medical and analytic work focused on the local economy, Guattari’s political commitments—to the Algerian struggle, workers’ movements, and other social fields—extended the presence of the hospital to the world beyond. The supposed presence of police around the clinic may or may not have had to do with the suitcases of cash for the FLN (The National Liberation Front for Algerian Liberation) which were rumored to be passing through, or the illegal abortions and contraceptives the staff provided to visitors. One could even argue for the radical threat of the “grid,” the clinic’s organizational system for practical operations that challenged established roles and functions through a rotating distribution of tasks, including medical duties. Pain and Guattari’s close friendship and collaborations led to several decentralized, collective efforts in alternative media, bringing together left-wing militants, artists, and scholars, from video workshops and publications within the FGERI (Federation of Groups for Institutional Study & Research) and its CERFI group (the Centre for Institutional Study, Research and Development), to the pirate radio stations Fédération des Radios Libres Non Commerciales (1978) and Radio Tomate (1981).

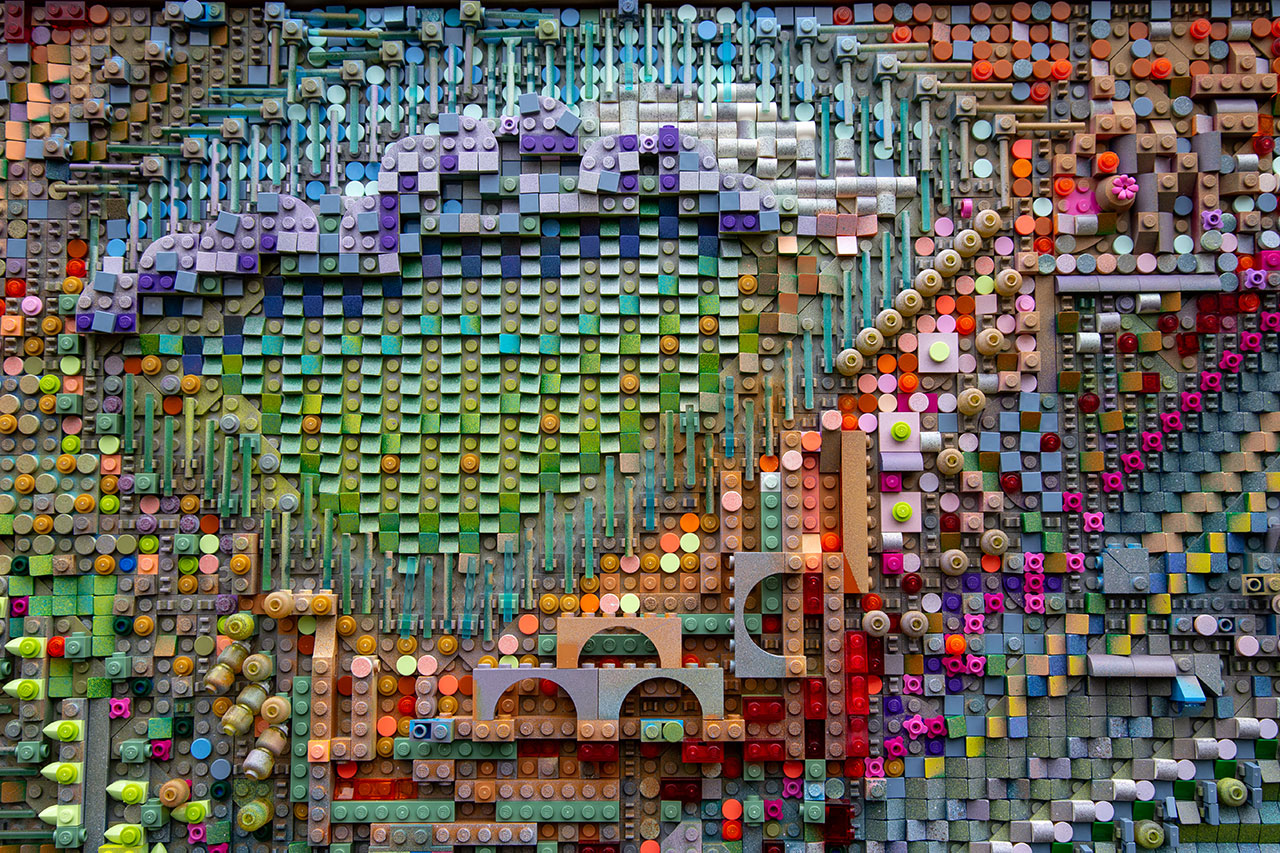

François Pain filming Min Tanaka at La Borde, 1986. Photograph by Jean-Michel Pain. Courtesy of François Pain.

Haunting any beginning amid catastrophe (like Pain’s film Institutional Psychotherapy as One of the Fine Arts…, 2025), like the birth of institutional psychotherapy in wartime and under fascism, is an inquiry into what remains: What is not merely disaster’s ruins, disaster’s returns?

The exhibition at JOAN presents Pain’s new film installation alongside older experimental films and a vitrine with materials from Pain’s personal archive. Pain’s installation is composed of nine screens, each of which is subject to a zealous vacillation of archival footage of wars being waged, daily life at Saint-Alban and La Borde, vignettes from Pain’s earlier films, contemporary protest marches, and intimate discussions with Tosquelles, Oury, and Guattari. These more personal vignettes, shot by Pain with a handheld camera, are inseparable and notably indistinguishable from the supposedly distanced camera that documents war scenes and workshops at Saint-Alban.

Accordingly, the structure of Institutional Psychotherapy as… marks and eclipses historical and aesthetic reference points, at risk of radically collapsing all nine screens as interchangeable and indistinct. Here is an enigma of the precarity of the collective assemblage (of enunciation), and of “madness,” in the collapses initiated by disaster—the disaster that is war, that is madness, that is being itself. The question of disaster is suspended between the loss of the world as it was and the world that is nearing existence; these worlds exist simultaneously. Catastrophe is related to the sometimes unbearable agony of inhabiting a world, the suffering of and desire for the Other, and social alienation, but it also resonates deeply with the particularities of mental alienation suffered in psychosis. Alienation, however, is not annihilation; madness is not totalizing destruction. The social persists, subjectivity persists, and there exists a constant and creative effort of reconstruction within and across film, “madness,” and sites of psychiatric care. Such attempts flash across nine screens: The same images repeat, as elsewhere in Pain’s practice, constructed and reconstructed in distinct forms and chance relations. The space between the screens is one of suspension, threshold, and discontinuity; on one screen, Guattari lays on the couch and speaks, but his transcribed speech appears on a different screen. The installation is a structure that disarticulates a coherent figure of producer and produced, transmitter and receiver, doctor and patient, filmmaker and filmed, and unfastens the striae that place the exegetic on one side and the diegetic on the other. It is a disorder that upsets the fixed site of the analytic couch. To create conflict, as Jean Oury says, is to create life.3 A reconstruction takes place against and by means of the inertia of the word. Scenes repeat in other screens, against isolation, against segregation.

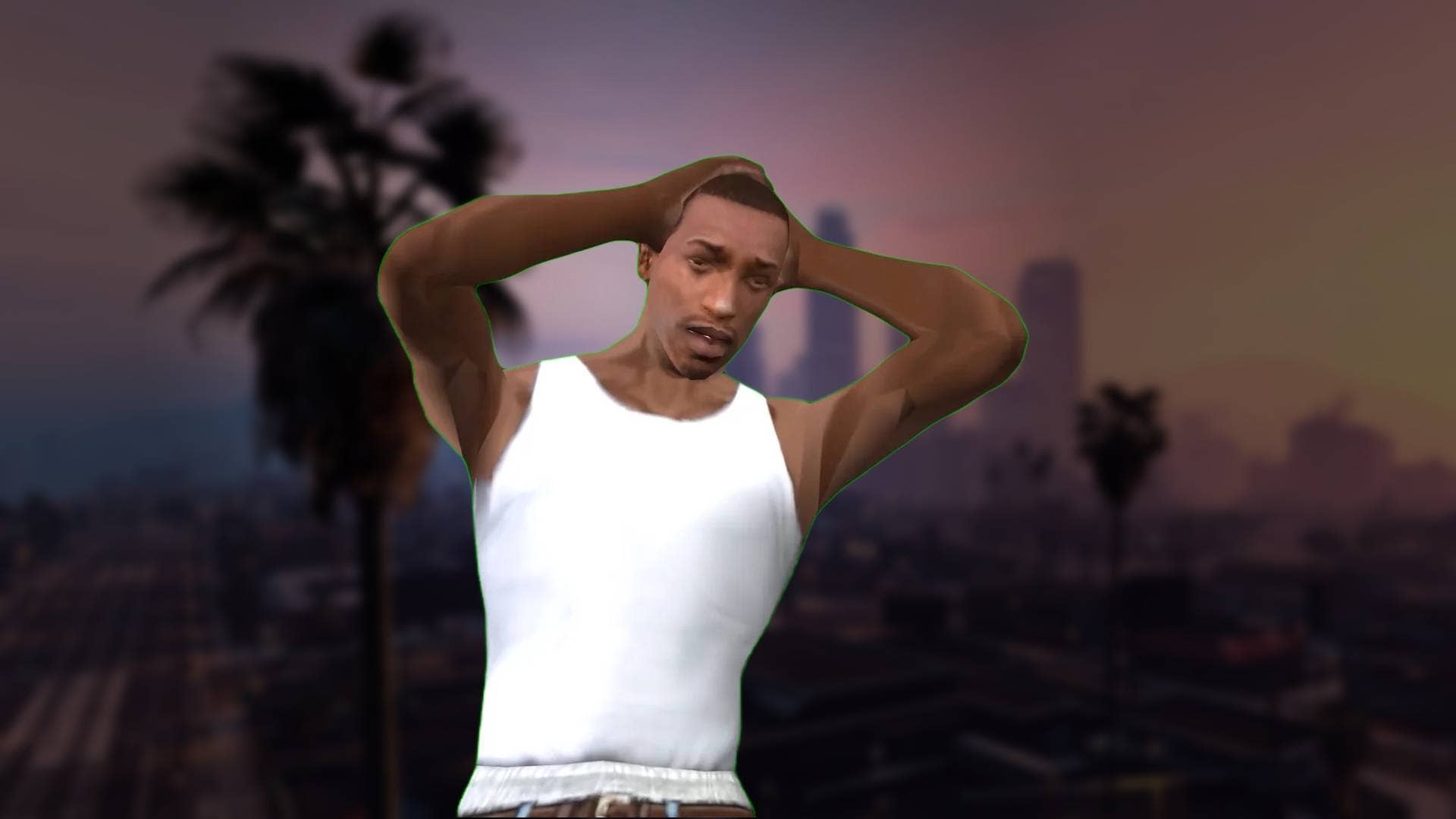

Happy New Order (François Pain, 1982). Courtesy of the artist and New Galerie.

The event ends, begins, and returns. “Shit! C’est encore la Guerre [It’s the War again],” reads the Dziga Vertov–inspired text card on the screen. As Frantz Fanon—who worked at Saint-Alban early in his career and clarified its ideas and practices throughout his own militant intellectual, medical, and political commitments—writes, “But the war goes on.”4 It returns and recalls, by way of the image, the gesture in circulation, reversal, and transmission. As Tosquelles says elsewhere in Pain’s archives, it is precisely the shitty object that does the constituting of the network, giving shape to the structure of the collective, of a group, of social life and its psychic economies. “With the war,” he exhorts, “comes the resistance.” Or, as Pain’s camcorder-commando film with his collective Canal Déchaîné proclaims, “Intifada Everywhere!”

Pain’s films are not an aestheticization of madness nor of politics, but an approach to image as encounter. His practice works as a social cinema, endlessly undertaking a rearrangement against social and psychic alienation, against established orders. There is a collective attempt, a treatment—if not a cure—of image. A network both precedes and proceeds the existential image.

“It's better not to say too much. Not even in my head!” A narrator voices the thoughts of a character wandering across Paris’s streets in The Green Notebook (1980), which opens the exhibition. Written by Guattari, the film meanders between a paranoid monologue, the titular lost notebook, and succeeding breakdowns of a break-up among memory, fantasy, subjectivity, and “reality.” It was initiated by an invitation to present at the Paris Biennale following Pain’s release from prison in February 1980. Pain had been arrested in 1979 at the trial of Franco Piperno, a leading figure in the movement for Italian workers’ autonomy, ostensibly for a photo placing him at a demonstration of metalworkers, which was published by a far-right magazine. Pain had been targeted for his involvement with Guattari, the Italian left, and illegal free radio stations. He surmises that he was a patsy, nabbed because the police could not arrest Guattari. His searing letter to the judge was published in the November 17 and 18 issue of the Libération newspaper. His months in prison were highly publicized and protested, and petitions for his release featured prominent names (including Jean-Luc Godard).

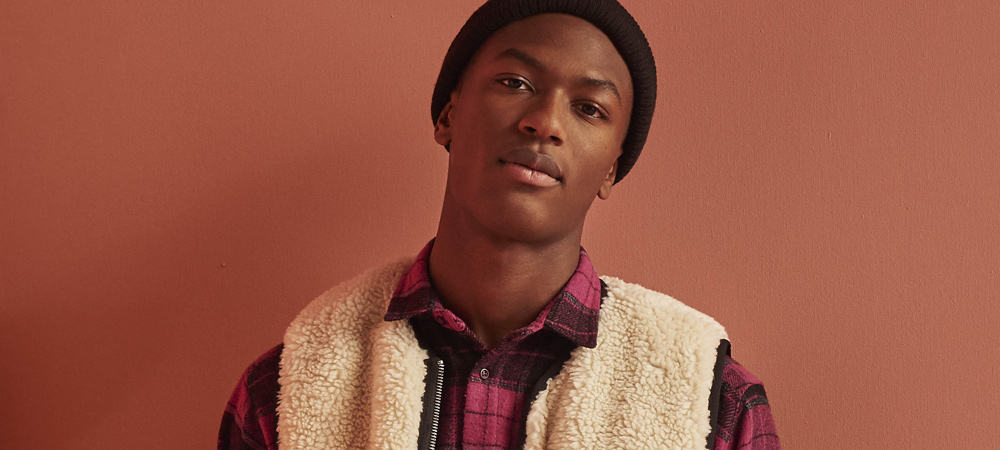

The Green Notebook (François Pain, 1980). Courtesy of the artist and New Galerie.

After his release, no longer welcome in the production facilities of the Institut National de l’Audiovisuel—which had once supported and produced his films, but whose director now refused to support “extreme leftists”—Pain would sneak in at night with the help of INA friends to colorize the film he shot in black and white. Using the small, handheld Paluche camera made film, for Pain, fingers that see,5 a bodily sensation of sight. The grid that sometimes appears onscreen in The Green Notebook materializes the slippages of the three-by-three grid in Institutional Psychotherapy as…. The obsession remains: to recover the lost letters.

Across the room plays The Crystal Wave (1985). Based on a story by the reclusive writer and pedagogue (and friend of Pain) Fernand Deligny, the film is a collective production made for an annual gathering of hospital clubs. At La Borde, Pain had been asked to organize a video workshop with patients to produce a film. Around 1973, Pain had founded the Imago group within CERFI to experiment with institutional analysis, education, and alternative information production and circulation through video. In the film, the residents of La Borde are warned of the imminent arrival of a wave of crystal, which will engulf and encapsulate all in its wake. The threat cannot be escaped. The solution? “Pose for posterity’s sake.”

Filming a few residents notifying others, one on horseback, two continuously climbing spiral staircases, the film travels the hospital grounds, through the rooms of the patient-managed club: from the library, bar, salon, and arts ateliers to the meeting rooms where decisions were collectively made. In one scene, sound is reverbed, slowed down, and warbled, already crystallizing. What is the act of artmaking, of filmmaking itself, if not a fixing of sorts, for eternity—a question of form, trace, and project? We watch as the crystal turns,6 the image moves, the presents pass with the gallop of the resident on horse and of the film through the gate of the camera.

Back in Paris, amidst an array of ephemera, photographs, and flyers on the wall of Francois’s studio, hangs a handwritten card that reads, “Time passes… that’s all it knows.”

- François Tosquelles, “Psychopathology and Dialectical Materialism,” in Psychotherapy and Materialism: Essays by François Tosquelles and Jean Oury, ed. Marlon Miguel and Elena Vogman. (Berlin: ICI Press, 2024), 66. ↩

- Anne Querrien and Constantin Boundas, “Anne Querrien, La Borde, Guattari and Left Movements in France, 1965–81.” Deleuze Studies 10, no. 3 (2016): 395–416. ↩

- Jean Oury, “Institutional Psychotherapy: From Saint-Alban to La Borde” in Psychotherapy and Materialism: Essays by François Tosquelles and Jean Oury, ed. Marlon Miguel and Elena Vogman (Berlin: ICI Press, 2024), 99. ↩

- Frantz Fanon, The Wretched of the Earth, translated by Richard Philcox (New York, NY: Grove Press, 2021), p. 181. ↩

- Pain constantly refers to Tosquelles’s sight at the tip of the fingers when he speaks of filming with the Paluche camera. ↩

- Gilles Deleuze, Cinema 2, The Time-Image, Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1989, 69. ↩

![‘Omukade’ Trailer – Thai Monster Movie Unleashes an Insane Giant Centipede Nightmare! [Exclusive]](https://i0.wp.com/bloody-disgusting.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/image-30.jpg?fit=1713%2C931&ssl=1)

![‘Sally’ Trailer: Acclaimed Sundance Doc About Trailblazing First Woman To Blast Into Space [Ned]](https://cdn.theplaylist.net/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/02065833/unnamed-2025-05-02T065720.586.jpg)