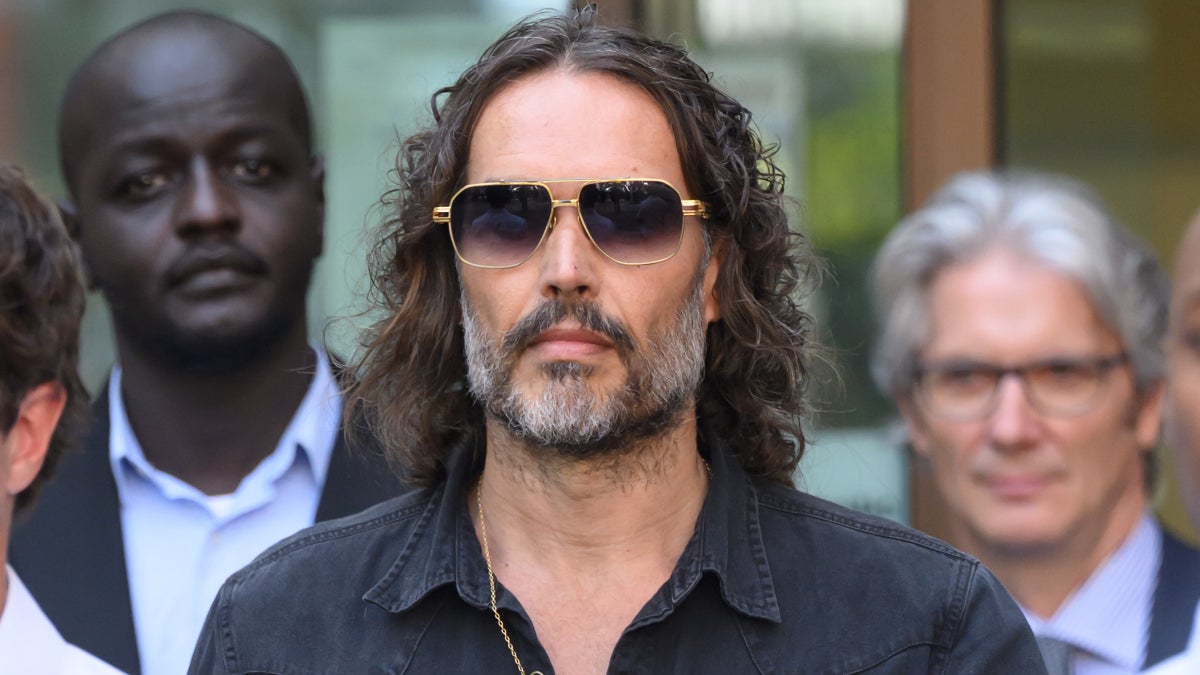

The Surfer Cements Nicolas Cage’s Late Career Renaissance

Early in The Surfer, Nicolas Cage‘s character confronts the local toughs who have chased him off the Australian beach he’s come to surf. Worse still, they’ve stolen his board! At first Cage tries to simply and request the return of his gear. But when the hooligans’ leader Scally (Julian McMahon) pretends to not understand the […] The post The Surfer Cements Nicolas Cage’s Late Career Renaissance appeared first on Den of Geek.

Early in The Surfer, Nicolas Cage‘s character confronts the local toughs who have chased him off the Australian beach he’s come to surf. Worse still, they’ve stolen his board! At first Cage tries to simply and request the return of his gear. But when the hooligans’ leader Scally (Julian McMahon) pretends to not understand the request, our hero loses his cool.

“Dude…” Cage says, his voice wavering and his finger wagging. “That’s my board, and I want it back!”

Even five years ago, Cage’s line reading would be the stuff of memes, shared in viral videos and turned into kitschy t-shirts and shower curtains. For more than a decade, Nicolas Cage held the somewhat ignominious title of the Internet’s Favorite Actor, with movie nerds (this writer chief among them) ironically praising his screaming about bees in The Wicker Man and shouting the alphabet in Vampire’s Kiss.

But then something strange happened. Once he got out of the tax debt that drove him to take every movie that came his way, Cage started making really, really good movies again. In masterpieces like Mandy, Pig, and Spider-Man: Into the Spider-Verse, and even uneven entries like Dream Scenario, Cage became a reliable source of onscreen pathos and excitement.

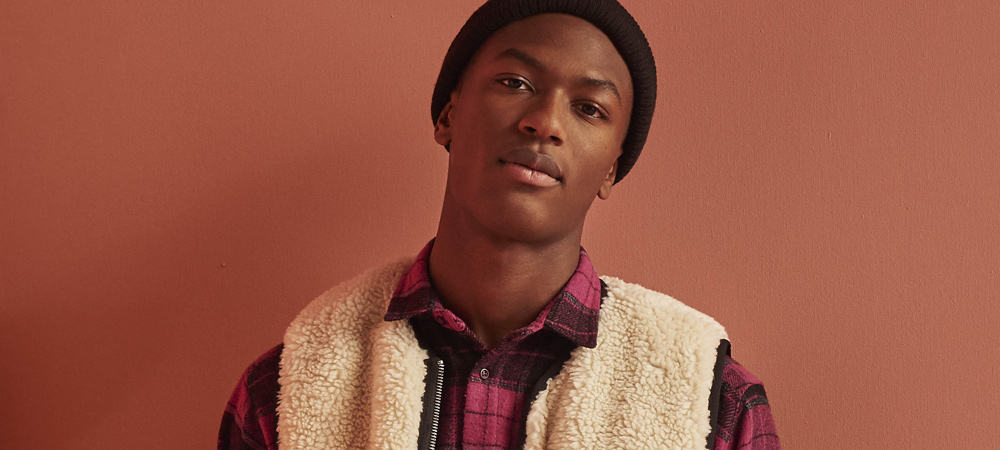

The change in esteem did not signal a change in Cage’s performance style. He still makes incredible choices. Rather it’s the filmmakers who have changed, finally figuring out how to best use Cage’s incredible talents. That’s particularly true in The Surfer, which casts Cage as a normal guy, an American square amongst Australian oddballs.

Breaking Away

At the start of The Surfer, Cage’s character, credited only as “the Surfer,” steps out of his luxury car and, along with his son (“the Kid,” played by Finn Little) heads down to an Australian beach to surf. The Surfer regales his reluctant son with stories about the glory of surfing this beach, of beloved memories he built before the death of his own father, which led him to leave Australia for America.

No sooner do they arrive at the water than a local called Bulldog (Alexander Bertrand) rushes onto the beach to confront them. “Don’t live here, don’t surf here,” he barks. The Surfer’s explanations—that he used to live here and is in the process of purchasing his father’s old house mere meters away—don’t dissuade Bulldog. “Don’t live here, don’t surf here,” he insists.

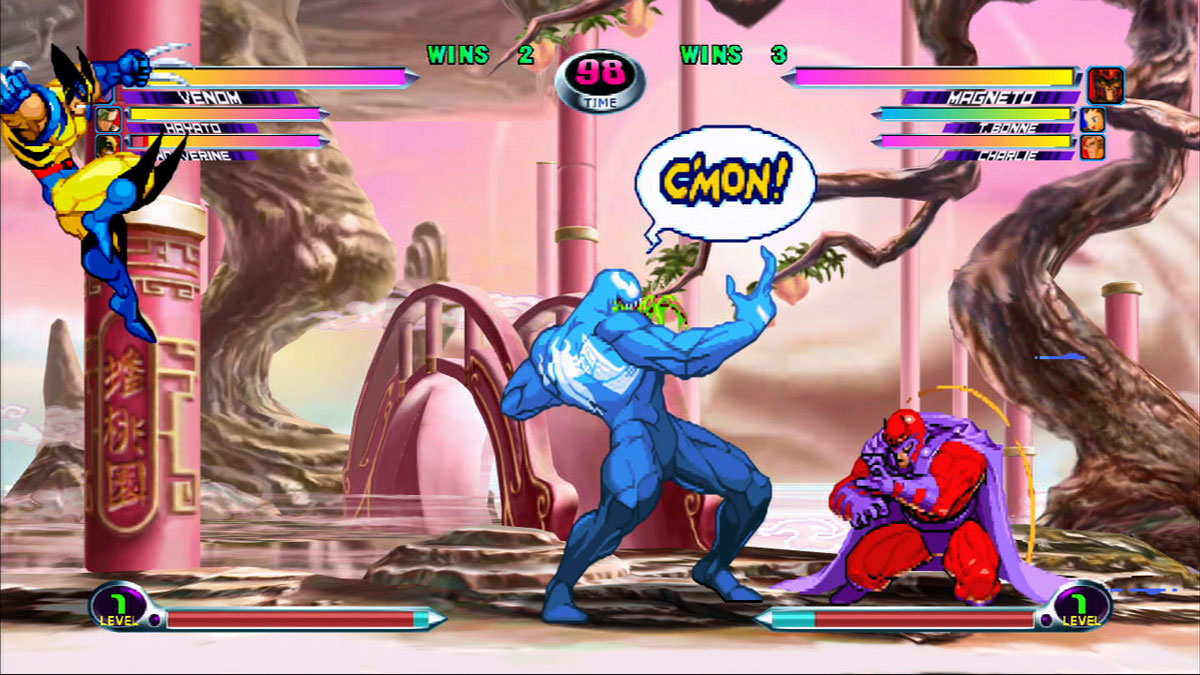

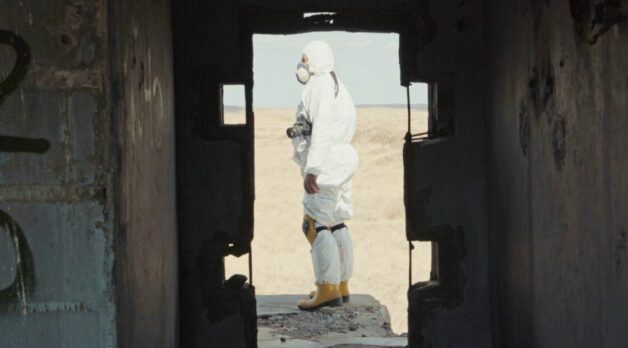

In part, The Surfer tells the story of the Surfer’s clashes with Scally, Bulldog, and his men, revelers who spout Joe Rogan-esque nonsense about masculinity while chasing away outsiders and other undesirables, mostly an unhoused man called Curly (Michael Abercromby). However, director Lorcan Finnegan and screenwriter Thomas Martin borrow heavily from Australian New Wave films, most notably 1975’s Wake in Fright, to craft an existential odyssey in which the ordeal strips the Surfer down to his essence.

As the guide on this odyssey, The Surfer uses Cage in a way we rarely see these days. He’s presented as the normal guy, the square who seems more at home in corporate offices and suburban neighborhoods than he does on the beach with Scally’s zen partiers.

Of course that veneer of normalcy falls away during the Surfer’s ordeal. Refusing to go no further than the parking lot between the beach and the house, going delirious from the sun and baffled by what may be a vast conspiracy pitted against him, the Surfer loses his identity. Finnegan’s surreal approach, full of zooms, close-ups, and unlikely edits, documents the Surfer’s undoing, as he becomes more and more like Curly. More and more like his father.

Cage embodies the Surfer’s descent with his signature strong choices. Midway through the movie, covered in sweat and blood, his shoes gone and his feet bared, the Surfer looks across the hazy distance to see himself standing on the ledge of the house he wants to buy, looking relaxed. In contrast to the contented expression that he uses for his happy second self, Cage pulls a slack-jawed smile that grows more awestruck as the camera pushes into his eyes.

The smile snaps when the Surfer hears his real estate agent (Rahel Romahn) showing the house to another set of clients. Cage straightens his back and adopts the stance of a businessman, one rightly furious that someone else might buy his dream house. But the facade of normalcy drops when the agent dismisses him as a vagabond, and Cage gets louder and bigger, waving his hands and pulling a wide-eyed, threatening smile to reassert his claim.

In these moments, Cage becomes the actor we’ve known and loved all these past years. But unlike the films from his infamous era, Cage’s absurd choices don’t break them movie. They enhance it.

Cage’s New Wave

Perhaps the greatest bit of acting in Cage’s career comes late in Pig, written and directed by Michael Sarnoski. Cage’s character from Pig has the opposite arc to his character in The Surfer, as he plays a vagabond named Robin who was once one of the most respected chefs in the business. When Robin and a flashy young executive called Amir (Alex Wolff) visit a fancy upscale restaurant, they’re greeted by the head chef (David Knell), a pompous man who Robin once fired for overcooking pasta.

Pig has plenty of big, over-the-top moments, including a sequence in which Robin gets pummeled in an underground fight club for service workers to get out their aggression. But in this scene, Cage goes preternaturally still. He’s not meek. Cage stares down the other chef, who gets more expressive as he tries to justify his life choices to Robin. But Cage remains still, barely lifting his voice above a whisper.

“They’re not real,” Cage’s character tells the blubbering chef. “You get that, right? None of it is real. The critics aren’t real. The customers aren’t real. Because this isn’t real. You aren’t real.”

It’s a tough monologue, one that ends with a surprising affirmation in which Robin challenges the chef to follow his passion instead of chasing acceptance. “We don’t get a lot of things to really care about,” he closes. Yet instead of delivering the lines as a big inspirational speech, Cage chooses to go smaller and tighter, coiling with an intensity that only puts more weight on his words.

While it’s the best moment in Cage’s late career, the Pig monologue is hardly the only great one. There’s the sequence in Panos Cosmatos’ Mandy in which his character Red, after being bound and brutalized by demonic bikers who burn his girlfriend (Andrea Riseborough) alive, stumbles back into his bathroom, bloody and covered in blood, and just screams incomprehensibly for 30 seconds. Meanwhile Oz Perkins dials everything in Longlegs up to 11, but Cage’s howling serial killer still stands out and unnerves. Even movies that cast Cage as a regular dad, such as Mom & Dad, Color Out of Space, and Dream Scenario rest on his ability to go nuts when the story shifts.

These films signal an important shift in the way directors use Cage. No longer are his strong choices out of place within his movies, better suited for clips online than feature films. Instead they are tools that directors can use to create compelling and coherent works. By building a weird film around Cage and letting him play the normal guy, The Surfer shows that his late-career ride has only just begun.

The Surfer opens in theaters now.

The post The Surfer Cements Nicolas Cage’s Late Career Renaissance appeared first on Den of Geek.

![‘Omukade’ Trailer – Thai Monster Movie Unleashes an Insane Giant Centipede Nightmare! [Exclusive]](https://i0.wp.com/bloody-disgusting.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/image-30.jpg?fit=1713%2C931&ssl=1)

![Why Marvel's Thunderbolts Killed [SPOILER], Explained By The Director](https://www.slashfilm.com/img/gallery/why-marvels-thunderbolts-killed-spoiler-explained-by-the-director/l-intro-1746120774.jpg?#)

![‘Sally’ Trailer: Acclaimed Sundance Doc About Trailblazing First Woman To Blast Into Space [Ned]](https://cdn.theplaylist.net/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/02065833/unnamed-2025-05-02T065720.586.jpg)