Shards of Glass: “The Girl with the Needle” at the End of the World

Magnus von Horn’s The Girl with the Needle is now showing on MUBI in many countries.The Girl with the Needle (Magnus von Horn, 2024).Let us begin with a bedtime story, the kind that troubles dreams: One day a demon manufactures a mirror that magnifies negatives, making flaws and deceptions more visible than ever. Within its frame, people look “hideous” and “so distorted that no one could recognize them,” yet they eagerly convey the “cunning invention” everywhere to expose “for the first time … what the world and mankind were really like.” Soon, some heave the mirror skyward, hoping to unhallow the angels. But it plummets to the ground and shatters, flinging shrapnel across the surface of the earth. Each small shard shares the power of the whole, a force that distorts victims and their views. All this is merely prologue. The rest of “The Snow Queen,” by Hans Christian Andersen, follows two children in a city too cramped for “even a little garden,” only window-box roses: a boy who is wounded and missing and a girl who, after a strange and disquieting journey, finds him again at “the end of the world.”This fairy tale, like all good speculative fiction, disturbs the future from the shelf of the present. It was written in the 1840s, a decade that theorized “world war” and popularized the daguerreotype, a photographic process on mirror-polished metal that, depending on your angle, could appear positive or negative. The story seems now to portend not only the twentieth century’s mass-produced horrors but also the mass-produced images of them, which expanded the range of disillusioned witnesses. (After all, the mirror shards become spectacles and window panes; why not a camera lens?) Set in Andersen’s native Copenhagen, in the wake of the First World War, The Girl with the Needle (2024) inherits this atmosphere of devastation. In its seamy city of unpeopled cobblestone streets and leaky garrets, rendered in stark black and white, gardens are unimaginable—any roses would bloom gray. The film, too, opens on a brief prologue: a procession of isolated human faces, projected with flickering shadows that multiply lips and noses, taffy-pulling eyebrows into livid lacerations. Are these subjects grimacing or grinning? Animated or still? Regardless, we are warned not to trust what we see.In the next shot, Karoline scrubs her hands before one of the film’s many mirrors. She works at a textile factory prospering from the deathless demand for military uniforms. (Their thick serge strains needles accustomed to delicate linen, white handkerchiefs once waved like white flags.) But wartime profits haven’t trickled down, and her request for a widow’s supplement hits a snag: Her husband, Peter, unheard from at the front, isn’t numbered among the official dead. Evicted from her apartment, where she’s behind on rent, Karoline boards a tram and rubs two peepholes into the fogged windows (just as Andersen’s children press stove-warmed pennies to their frozen window panes, to peer at each other across adjoining roofs). Instead of cutting from Karoline to her outlook, director Magnus von Horn reflects the passing jumble of buildings, silhouetted in pewter light, within her frame-filling eye, bringing us close enough to hear its sticky, shutterlike blink. Our perspective, however shaky, is squarely with Karoline; throughout, her wide-aperture exposure to raw experience develops her into something new.This framing occurs once more, after a substantial change in circumstances. Again Karoline faces a mirror. On a ledge rests a knitting needle, pilfered perhaps from the job she has since lost, after the boss impregnates, affiances, and abandons her, cowed by his upper-class mother’s hauteur. Meanwhile Peter has come home, unwelcomed and at first unrecognized, an inert mask cupping his blasted-out jaw and a nightly injection of morphine prescribed to soothe his screams. To induce miscarriage in a public bath, Karoline stabs at her womb with that needle, a choice of object that sutures the feminized work of costuming soldiers to a narcotic for the so-called lucky ones who survived. “You don’t stick a needle in yourself if you’re fine,” scolds a passerby, Dagmar Overbye, who staunches Karoline’s bleeding and then offers to take in the coming child, for a fee. It is Dagmar who bestows the film’s fairy-tale title upon Karoline when the younger woman shows up, months later, to forfeit her newborn daughter, one of dozens who have done the same, all noted neatly in Dagmar’s locked-away logbook.For first-time viewers outside her native Denmark, where she remains infamous, there is something of a twist: Dagmar Overbye was real. Her crimes have been exhaustively documented and interpreted, and are declared in the film by an end-credits card. Still, I resist recounting them. I worry that a litany of methods, motives, or body counts might catalog and tuck away into some dusty drawer labeled “DEVIANTS” a horror that the film limns less as isolated and indiv

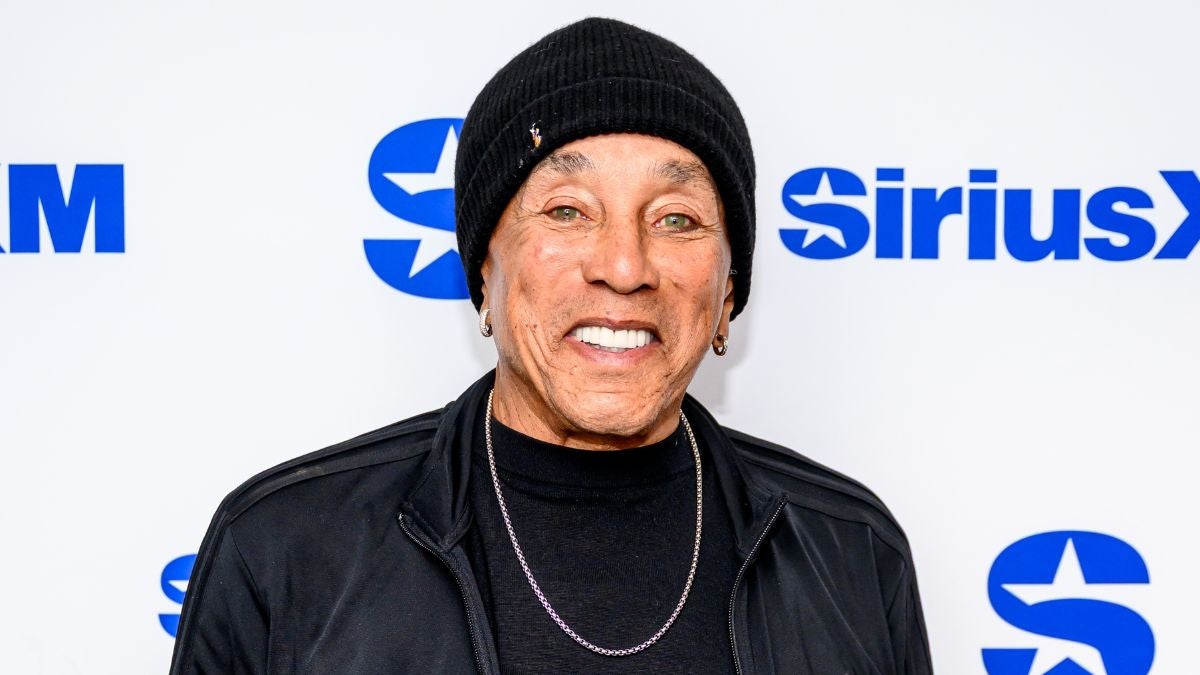

Magnus von Horn’s The Girl with the Needle is now showing on MUBI in many countries.

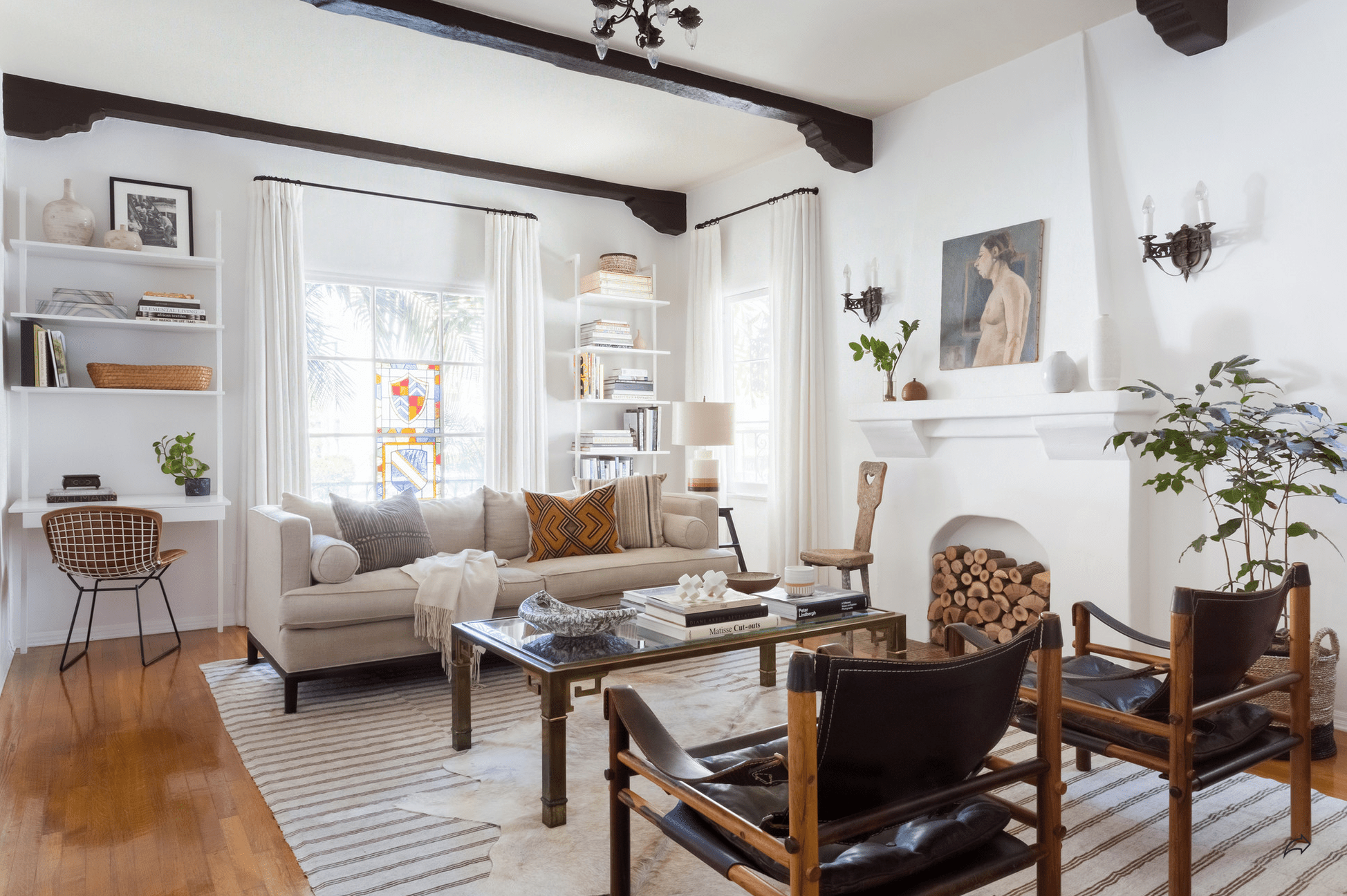

The Girl with the Needle (Magnus von Horn, 2024).

Let us begin with a bedtime story, the kind that troubles dreams: One day a demon manufactures a mirror that magnifies negatives, making flaws and deceptions more visible than ever. Within its frame, people look “hideous” and “so distorted that no one could recognize them,” yet they eagerly convey the “cunning invention” everywhere to expose “for the first time … what the world and mankind were really like.” Soon, some heave the mirror skyward, hoping to unhallow the angels. But it plummets to the ground and shatters, flinging shrapnel across the surface of the earth. Each small shard shares the power of the whole, a force that distorts victims and their views. All this is merely prologue. The rest of “The Snow Queen,” by Hans Christian Andersen, follows two children in a city too cramped for “even a little garden,” only window-box roses: a boy who is wounded and missing and a girl who, after a strange and disquieting journey, finds him again at “the end of the world.”

This fairy tale, like all good speculative fiction, disturbs the future from the shelf of the present. It was written in the 1840s, a decade that theorized “world war” and popularized the daguerreotype, a photographic process on mirror-polished metal that, depending on your angle, could appear positive or negative. The story seems now to portend not only the twentieth century’s mass-produced horrors but also the mass-produced images of them, which expanded the range of disillusioned witnesses. (After all, the mirror shards become spectacles and window panes; why not a camera lens?) Set in Andersen’s native Copenhagen, in the wake of the First World War, The Girl with the Needle (2024) inherits this atmosphere of devastation. In its seamy city of unpeopled cobblestone streets and leaky garrets, rendered in stark black and white, gardens are unimaginable—any roses would bloom gray. The film, too, opens on a brief prologue: a procession of isolated human faces, projected with flickering shadows that multiply lips and noses, taffy-pulling eyebrows into livid lacerations. Are these subjects grimacing or grinning? Animated or still? Regardless, we are warned not to trust what we see.

In the next shot, Karoline scrubs her hands before one of the film’s many mirrors. She works at a textile factory prospering from the deathless demand for military uniforms. (Their thick serge strains needles accustomed to delicate linen, white handkerchiefs once waved like white flags.) But wartime profits haven’t trickled down, and her request for a widow’s supplement hits a snag: Her husband, Peter, unheard from at the front, isn’t numbered among the official dead. Evicted from her apartment, where she’s behind on rent, Karoline boards a tram and rubs two peepholes into the fogged windows (just as Andersen’s children press stove-warmed pennies to their frozen window panes, to peer at each other across adjoining roofs). Instead of cutting from Karoline to her outlook, director Magnus von Horn reflects the passing jumble of buildings, silhouetted in pewter light, within her frame-filling eye, bringing us close enough to hear its sticky, shutterlike blink. Our perspective, however shaky, is squarely with Karoline; throughout, her wide-aperture exposure to raw experience develops her into something new.

This framing occurs once more, after a substantial change in circumstances. Again Karoline faces a mirror. On a ledge rests a knitting needle, pilfered perhaps from the job she has since lost, after the boss impregnates, affiances, and abandons her, cowed by his upper-class mother’s hauteur. Meanwhile Peter has come home, unwelcomed and at first unrecognized, an inert mask cupping his blasted-out jaw and a nightly injection of morphine prescribed to soothe his screams. To induce miscarriage in a public bath, Karoline stabs at her womb with that needle, a choice of object that sutures the feminized work of costuming soldiers to a narcotic for the so-called lucky ones who survived. “You don’t stick a needle in yourself if you’re fine,” scolds a passerby, Dagmar Overbye, who staunches Karoline’s bleeding and then offers to take in the coming child, for a fee. It is Dagmar who bestows the film’s fairy-tale title upon Karoline when the younger woman shows up, months later, to forfeit her newborn daughter, one of dozens who have done the same, all noted neatly in Dagmar’s locked-away logbook.

For first-time viewers outside her native Denmark, where she remains infamous, there is something of a twist: Dagmar Overbye was real. Her crimes have been exhaustively documented and interpreted, and are declared in the film by an end-credits card. Still, I resist recounting them. I worry that a litany of methods, motives, or body counts might catalog and tuck away into some dusty drawer labeled “DEVIANTS” a horror that the film limns less as isolated and individual than as far-reaching and social. The Girl with the Needle does not psychologize Dagmar or sift through her history for clues, as might a rote biopic or prurient podcast detective. Nor does it trace the policemen’s trail to her door, but instead, it places us in the room with her, and with Karoline. Karoline, short of the foster fee, barters her services as wet nurse to Dagmar’s ostensible seven-year old daughter, Erena, and moves into the basement.

The Girl with the Needle (Magnus von Horn, 2024).

“One reason why motherhood is often so disconcerting,” Jacqueline Rose writes in Mothers: An Essay on Love and Cruelty, “seems to be its uneasy proximity to death.” The mother pushes non-life into life; the murderer, life into death. (Only one letter severs the words in Danish: mo[r]der.) Infanticide inverts the first act of motherhood—the source, perhaps, of the crime’s added charge. Through Karoline, we have already seen it all: the factory boss sending a guilty envelope of cash, scant provision for a whole life-to-be, not to mention its caretaker; a coworker flinching from her baby’s piercing wails; a tenant cuffing her towheaded toddler, who spurts forth blood and tears. “I doubt a mother wants her child killed,” a judge eventually declares to Dagmar.

The boss’s mother, after having Karoline’s pregnancy verified on a makeshift examination table, asks: “Can it be taken care of?” She is referring, of course, to abortion—often workable for the rich or well-connected—but the English subtitles suggest another meaning: Once born, can the child ever hope to be cared for? The doctor replies as if answering both questions: “It’s too late, I’m afraid.” Parents are weary, overburdened, incurious, callous, distracted, dead; child-rearing expensive and embattled; opting out criminalized. (Not until 1973 would Denmark legalize abortion, a precondition for planned parenthood, there being no consent without the possibility of refusal.) Little wonder those at Dagmar’s door gulp down a gumdrop fairy tale—foundlings whisked away to big, clean manors with magically benevolent minders—as tooth-decaying as the jarred confections that Dagmar, dwelling above her candy store, never seems to sell.

Any impulse to analyze Dagmar is made even more redundant by the blank, slack-jawed presence of Karoline, whose story could be Dagmar’s own. Throughout the film, Karoline mirrors the world around her, often meeting the camera’s gaze in strikingly centered, portrait-like compositions. When she and her boss stroll down parallel sidewalks, she playfully mimics his limping gait. Later he wraps her in a crinkly lamé gown—the first of many times another dresses Karoline like a doll. After Erena bemoans Karoline’s slum-soiled stench, Dagmar rushes Karoline off to the public bath where they met, scrubbing and sprucing her up in a polka-dot shift, primly buttoned to the top. Dagmar grooms the plastic, impressionable Karoline into her double, her daughter, another mother to Erena, her accomplice. She even teaches Karoline her ritual of absolution, the magic words they each intone to soothe those surrendering their babies: “You’re doing the right thing.” When Karoline’s willingness to play her part weakens, Dagmar brushes her hair or administers drops of ether (at the time, a common anesthetic used during childbirth).

The Elephant Man (David Lynch, 1980).

The theory of maternal impression, or maternal imagination, proposed that disorders, defects, indeed all manner of “monstrous births” were incarnations of thoughts or experiences had during pregnancy. The implications are volatile and conveniently unequal. But there is something touching in this idea that a mother’s circumstances are significant enough to twist marrow and sinew, to knit new cellular scripts. One believer was the nineteenth-century Englishman Joseph Merrick, who often retread this scrap of family lore: Frightened by a fairground elephant, his expectant mother afterward bore a child—himself—who took the form of her fear. An uncertain condition had given Merrick “sack-like masses of flesh covered … by cauliflower skin,” “a fin or paddle rather than a hand,” and “an osseous growth on the forehead [that] almost occluded one eye.” These descriptions come courtesy of Dr. Frederick Treves, who ogled Merrick in an illicit sideshow, where he was billed as “The Elephant Man,” and in the hospital where Merrick later lodged as a cause célèbre. (Treves titled his memoir after the sobriquet of his most famous client, not unlike von Horn’s anti-biopic of Dagmar.)

In The Elephant Man (1980), David Lynch canonizes the Merricks’ domestic sense-making as myth. The film opens and closes on the mother’s face, like twinned icons snapped into a double-sided locket: first her oval portrait—one Merrick cherishes by his bedside—and later her torquing visage as doubly-exposed elephants charge through it. By the end, she floats upward, bodiless and eternal, much like Lynch’s living dead girl Laura Palmer. In Dr. Treves’s colder, more rational view, Merrick’s “worthless and inhuman” mother abandons her malformed infant. Regardless, the mother is overburdened with responsibility and meaning: In fact, she was herself judged a “cripple” in life, and her death left Merrick at the spotty mercy of a stepmother, who had her own children, and the workhouse, whence he fled willingly to the steady if imperfect employment of the circus.

At the circus, Merrick was overexposed: Patrons paid to see there what they would turn away from in the street. At the hospital he is invisibilized: available by appointment, and only to polite company. Celebrities, even royalty, arranged to visit Merrick just to smile at him, and perhaps to see the pleasure he took in their smile, by which they hoped to absolve themselves of their revulsion. Did Merrick accept how he looked, I wonder, or how others didn’t? In fact, Treves “would not allow a mirror of any kind in his room,” to which he credits Merrick’s timid acceptance of his own “unsightliness,” a word that might fault him for the looker’s wish not to see. In his essay “The Monster Is Afraid,” critic Serge Daney calls Merrick “a mirror” to society. It is not Merrick who wears a mask, but his visitors, who don a “mask of politeness that conceals what they feel at his sight.” An actress (“a guest star,” quips Daney) arranges an audience and prides herself that “not one muscle of her face twitches” in Merrick’s company—proof less of her compassion than her professional acumen. “The social mask has been entirely reconstituted,” writes Daney, and Merrick, glad to glimpse something other than the horror he often inspires, “takes the heart of artifice for the truth.” Where circusgoers pay to stoke and exercise their disgust, Merrick’s hospital visitors seek the opposite transaction, leaving convinced anew of the world’s goodness by their act of charity. But as with Dagmar, the relationship between spectacle and audience is symbiotic: Merrick is accepted, his visitors cleansed; the mothers are forgiven and unburdened, Dagmar privately useful and then publicly condemned.

The Girl with the Needle (Magnus von Horn, 2024).

The First World War was brought to a close in 1919 with the Treaty of Versailles, signed in the palace’s Hall of Mirrors. Thus Germany was disarmed in the same room where—48 years, a lifetime, prior—it had been born. There are theaters of war, and there are also theaters of peace. Among the dignitaries stood a band of “broken faces”—a term given to veterans with grievous facial injuries—tasked with parading their war-riven visages before the crowd. Many of these men would have been denied mirrors during their convalescence; Harold Gillies, a pioneering plastic surgeon of the time, forbade them, fearing the truth would make his patients lose heart. Ironically, the men were cast as mirrors themselves—the embodied consequences of a conflict that some wanted to sequester firmly in the past.

Karoline does not see her husband’s injuries in full until she chances upon the circus where he is one of the acts. Within the tent, the ringmaster instructs Peter to remove his mask—painted on like a doll’s face and affixed, like many of the era, with false spectacles—and dares audience members to gaze into, even to touch, his face. On the left side, his ear and his glassy, vacant eye slant downward on an unnatural incline; where nose and lips should be sit a gnarled mass, like knotted bark, and a four-pointed void of flesh, through which jagged teeth gleam like stalactites. Mask or no, Peter’s face, like those superimpositions in the prologue, offers scant insight into how he feels, so we must search elsewhere (slumped shoulders, lisped words struggled through his facial cavity) for information.

The circus burlesques reality: Just after a little person suckles at a bearded lady’s nipple, a masked Peter marches mechanically, like a wind-up soldier, before a jeering crowd. Mothering segues seamlessly into war, as though our civilizations only reproduce in order to destroy each other’s children, rendering all manner of care pointless. Peter’s presence haunts Karoline’s time with Dagmar; she sees him in the scrunched-up faces of just-born babes, especially one bearing a cleft lip, and as a rasping apparition in her basement bedroom, where she leaks milk.

Onstage at the circus, Karoline can perform care for Peter, fixing her face into a mask of acceptance and even affection to defy the disgusted audience. That performance becomes real. Her onstage kiss heals (for a spell) their divide; it is then that she welcomes him back into her apartment, where he contorts into the fetal position and wails in his sleep like a baby. She has already kicked him out once—her first rejection of motherhood.

Karoline attends Dagmar’s trial, itself like a circus—a ritualistic rejection of what society fears, tucking their horror away inside a single individual rather than acknowledging it is atmospheric, widespread. Earlier in the film, Dagmar explained herself thus: “The world is a horrible place. But we need to believe it's not so. Do you understand?” (Karoline answers, “No.”) But now Dagmar forces the unsustainability of the current social order on her audience, arranged in a stagelike semicircle: “I only did what was necessary … what you’re too scared to do.” In her book, Rose writes that “in an inhuman world a mother can only be a mother in so far as history permits, which might mean killing your child” and that “when [the world] cannot bear to confront its own cruelty, the punishing of mothers darkens and intensifies.” Unlike the women assembled in the courtroom, Karoline does not shout to condemn Dagmar, to soothe her own complicity in her crimes and the connection the two women briefly shared. As on the circus platform with Peter, Karoline simply watches with her blank, open gaze—and it is only through her final act that we learn some of what she must feel.

The Girl with the Needle (Magnus von Horn, 2024).

Disenchantment has a negative connotation, but the cheerful denouements of fairy tales are marked by their stubborn recourse to reality. In “The Snow Queen,” Andersen is careful not to totally refute the mirror’s view: “Everything good or beautiful that was reflected in it almost [shrank] to nothing, while everything that was worthless and bad looked increased in size and worse than ever” (emphasis mine). At stake isn’t truth, then, but perspective. Pierced by a stray shard, the boy suddenly spies worms wriggling among the “crooked” roses, while “every flake of snow was magnified … much more interesting than looking at real flowers. There is not a single fault in it.” Soon he rattles off square acreage, borders, facts and figures, like a little general. Only tolerating perfection, he prefers the rational, the complete, the dead above the living. The real Dagmar Overbye was christened “The Angel Maker,” a moniker that might sound peaceful—couldn’t heaven use more angels?—until you picture a gravestone cherub, frozen forever in innocence, never to grow up.

When Andersen’s girl and boy return home, nothing has changed, except that they are older. They note the roses in full bloom but not the worms, whom we assume still wend their way through the soil unheeded. Their dark memories lift, like a weight, as they sit beside each other, hand in hand. Near the end of The Girl with the Needle, Karoline returns to Peter and finds him traveling with the circus, where carousing performers dine alfresco, chattering and clinking glasses. I am reminded of the camaraderie in Tod Browning’s Freaks (1932), or, in The Elephant Man, when Merrick’s fellow carnies uncage him and dance a torchlit escape through the forest. The circus, which might at first have seemed sinister or exploitative, here provides a release valve for social fears, an imperfect haven for scattered misfits. Karoline and Peter, sitting side by side in his caravan, resemble a shy, mannered engagement portrait, the kind Peter might have pocketed for the front. They twin within his armoire’s oval mirror, cobbling together one whole: each offers an unblemished cheek, a lifted hand. Soon the lost daughter returns—as though magically aged up—via Erena, whom Karoline adopts from the state orphanage where she has been slotted among endless rows of bassineted babes and refectories of praying kids presided over by nuns. When the orphanage head goes to retrieve Erena, Karoline looks askance at the camera with an expression that could be defiance, weariness, or acceptance. But when she steps from the corridor’s shadows into the light where Erena can see her, faint smiles flit over both of their faces. Is this, implausibly, a happy ending?

Were Karoline to tuck her into bed and read “The Snow Queen,” Erena might wonder aloud what happens to the villain of the title, whose cold kisses almost smothered the little boy. Is she defeated, disempowered, nothing but a bad dream? No, she has simply strayed off somewhere, shrouding faraway mountains with snow. Andersen does not tie up his tale with the reconstitution of a just world. “One of the agonies of being a mother,” Rose writes, is “to find that your child harbors … a story from which you had hoped against hope, once and for all, to free them.” Though Dagmar Overbye’s case changed childcare laws—spurring a system to count all citizens, including those adopted and born out of wedlock—it could not redistribute the lopsided burdens on mothers or make a safer world. Andersen’s boy and girl “become as little children,” but they cannot recoup their lost childhood. Shards of the broken mirror linger in the air, in the soil, poisoning landscapes and bodies, like unburst mines or toxins seeding the cratered fields. What comes after the end of the world? I do some quick math: When Copenhagen is invaded during the Second World War, Erena will be in her twenties.

![White Paper Games Announces Psychological Thriller ‘I Am Ripper’ [Trailer]](https://bloody-disgusting.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/iamripper.jpg)

![Hollow Rendition [on SLEEPY HOLLOW]](https://jonathanrosenbaum.net/wp-content/uploads/2010/03/sleepy-hollow32.jpg)

![It All Adds Up [FOUR CORNERS]](https://jonathanrosenbaum.net/wp-content/uploads/2010/08/fourcorners.jpg)