Children Make Movies

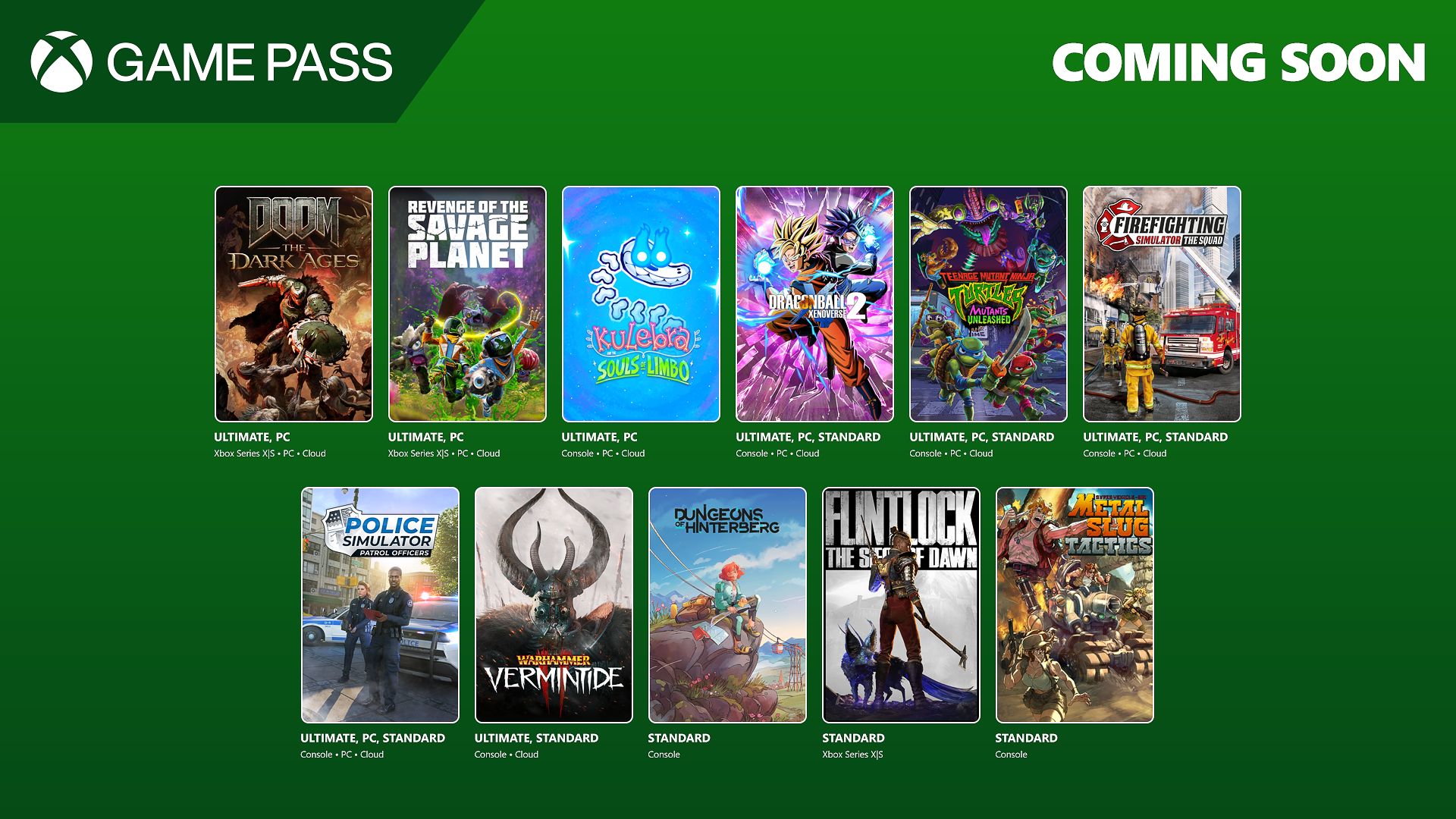

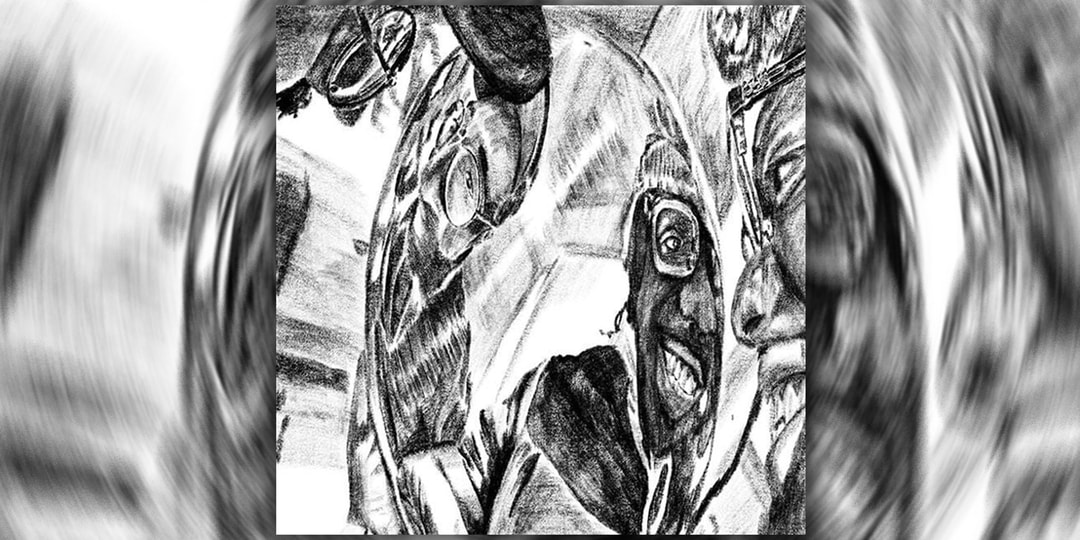

A Place Called Lovely (Sadie Benning, 1992).On Christmas day in 1988, a fifteen-year-old from Milwaukee received a toy camera from their dad. The Fisher-Price PXL-2000, or Pixelvision, was the first camcorder marketed to children and teenagers, and it left young Sadie Benning unimpressed: “This is a piece of shit. It's black-and-white. It's for kids. He’d told me I was getting this surprise. I was expecting a camcorder.”1Launched in 1987 at Manhattan’s International Toy Fair, Pixelvision’s main innovation was to record sound and image directly onto audio cassettes, making it cheaper and easier to shoot than a regular camcorder. Fisher-Price stopped production after only a year. The camera that was initially sold in toy shops was ultimately destined for the yard sale. And yet, on the road to the growing scrap heap of obsolete media, Pixelvision garnered an unlikely following among a coterie of adult artists and filmmakers—Richard Linklater, Peggy Ahwesh, Craig Baldwin, and Michael Almereyda among them. This was partly thanks to its accessible price range as well as its distinctive low-resolution visuals, densely pixelated in black and white. Sadie too would grow to love their Pixelvision, exploring their sexuality, fears, and frustrations with suburbia in a tone that was at once intimate, confessional, grungy and politically urgent. From the safety of their childhood bedroom, they created landmarks of queer video art whose reputation would soon rival the experimental films of their father, James Benning. Although Pixelvision was dismissed as a commercial failure, the technology can tell us much about the sorely neglected world of children’s filmmaking. Though this canon is vast and appropriately unruly, the idea that children and young people make movies still feels novel, maybe even revolutionary. This is true even when it’s coming—as it so often does—from the cradle of a massive toy corporation. “You’ve always been heard, but now you can be seen,” was Pixelvision’s promotional tag line, while Bob Fisher would hail it in Popular Science as a tool that “opens up a technical and creative world to children.”2 Later toys for children, like the TOMY Kid Cam (1991), a replica of a camera that didn’t actually record, and the Lego Steven Spielberg MovieMaker (2000),3 which recorded using a digital camera, also trumpeted this liberatory line, inviting children to seize the means of production using cheap, portable equipment. So why wasn’t Pixelvision a bestseller?“Kids said it sucked,” Geri Fialka, the founder of PXL THIS, a long-running festival dedicated to films made with Pixelvision, tells me. “They wanted color because of MTV. They wanted to make music videos.” Aside from struggling to compete with the aesthetics of commercial television and color home camcorders, Pixelvision’s temperamental technology was liable to glitch, and along with its relatively high cost (much less than other camcorders, much more than other toys) was deemed incompatible with the market at that time. Maybe there were other issues at play, too. Were the visuals too crunchy or abstract for young aesthetes? Did children like the idea of making a film rather than its often complicated reality? Unlike painting or drawing, solitary activities that can be easily picked up, filmmaking requires a level of guidance, collaboration, and technical know-how—though Pixelvision’s point-and-shoot technology significantly simplified the filming process. Just because parents weren’t purchasing Pixelvision in the volume that Fisher-Price had hoped for doesn't mean that children weren’t shooting movies. They were, and Fialka has been showing them at PXL THIS since 1991. Advertisement promoting Fisher-Price’s PXL-2000 toy camera (1988).PXL THIS festival does not distinguish between work by amateurs or professionals, children or adults. The youngest artist to screen there, Rubi Qi Tondelli, was only four years old. Fialka tells me that some of the most successful work shown at the festival has been made by children because they are the best at merging form and content: who better than a child to capture the essence of a toy camcorder? Fialka singles out the purity of vision and lack of intentionality as key reasons that the Pixelvision work of children is often so impressive. “If you try to make a film with Pixelvision and have it look profound, it won’t work. But if you have the innocence of a kid’s eye, it may turn out looking profound.” The work of eight-year-old Juniper Woodbury is one such example. An audience favorite at the thirteenth edition of PXL THIS in 2003, Woodbury’s Pixel work is exploratory, playful, and “pure,” in the sense of being unedited or digitally manipulated.4 The four-minute-long About Flowers, which begins with handwritten intertitles, takes a “bee’s-eye view” of a flower bouquet. Woodbury’s camera pushes in on the stamen of a bloom as she passionately narrates the recent findings from her biology class, moving between flower to fl

A Place Called Lovely (Sadie Benning, 1992).

On Christmas day in 1988, a fifteen-year-old from Milwaukee received a toy camera from their dad. The Fisher-Price PXL-2000, or Pixelvision, was the first camcorder marketed to children and teenagers, and it left young Sadie Benning unimpressed: “This is a piece of shit. It's black-and-white. It's for kids. He’d told me I was getting this surprise. I was expecting a camcorder.”1

Launched in 1987 at Manhattan’s International Toy Fair, Pixelvision’s main innovation was to record sound and image directly onto audio cassettes, making it cheaper and easier to shoot than a regular camcorder. Fisher-Price stopped production after only a year. The camera that was initially sold in toy shops was ultimately destined for the yard sale. And yet, on the road to the growing scrap heap of obsolete media, Pixelvision garnered an unlikely following among a coterie of adult artists and filmmakers—Richard Linklater, Peggy Ahwesh, Craig Baldwin, and Michael Almereyda among them. This was partly thanks to its accessible price range as well as its distinctive low-resolution visuals, densely pixelated in black and white. Sadie too would grow to love their Pixelvision, exploring their sexuality, fears, and frustrations with suburbia in a tone that was at once intimate, confessional, grungy and politically urgent. From the safety of their childhood bedroom, they created landmarks of queer video art whose reputation would soon rival the experimental films of their father, James Benning.

Although Pixelvision was dismissed as a commercial failure, the technology can tell us much about the sorely neglected world of children’s filmmaking. Though this canon is vast and appropriately unruly, the idea that children and young people make movies still feels novel, maybe even revolutionary. This is true even when it’s coming—as it so often does—from the cradle of a massive toy corporation. “You’ve always been heard, but now you can be seen,” was Pixelvision’s promotional tag line, while Bob Fisher would hail it in Popular Science as a tool that “opens up a technical and creative world to children.”2 Later toys for children, like the TOMY Kid Cam (1991), a replica of a camera that didn’t actually record, and the Lego Steven Spielberg MovieMaker (2000),3 which recorded using a digital camera, also trumpeted this liberatory line, inviting children to seize the means of production using cheap, portable equipment. So why wasn’t Pixelvision a bestseller?

“Kids said it sucked,” Geri Fialka, the founder of PXL THIS, a long-running festival dedicated to films made with Pixelvision, tells me. “They wanted color because of MTV. They wanted to make music videos.” Aside from struggling to compete with the aesthetics of commercial television and color home camcorders, Pixelvision’s temperamental technology was liable to glitch, and along with its relatively high cost (much less than other camcorders, much more than other toys) was deemed incompatible with the market at that time. Maybe there were other issues at play, too. Were the visuals too crunchy or abstract for young aesthetes? Did children like the idea of making a film rather than its often complicated reality? Unlike painting or drawing, solitary activities that can be easily picked up, filmmaking requires a level of guidance, collaboration, and technical know-how—though Pixelvision’s point-and-shoot technology significantly simplified the filming process. Just because parents weren’t purchasing Pixelvision in the volume that Fisher-Price had hoped for doesn't mean that children weren’t shooting movies. They were, and Fialka has been showing them at PXL THIS since 1991.

Advertisement promoting Fisher-Price’s PXL-2000 toy camera (1988).

PXL THIS festival does not distinguish between work by amateurs or professionals, children or adults. The youngest artist to screen there, Rubi Qi Tondelli, was only four years old. Fialka tells me that some of the most successful work shown at the festival has been made by children because they are the best at merging form and content: who better than a child to capture the essence of a toy camcorder? Fialka singles out the purity of vision and lack of intentionality as key reasons that the Pixelvision work of children is often so impressive. “If you try to make a film with Pixelvision and have it look profound, it won’t work. But if you have the innocence of a kid’s eye, it may turn out looking profound.”

The work of eight-year-old Juniper Woodbury is one such example. An audience favorite at the thirteenth edition of PXL THIS in 2003, Woodbury’s Pixel work is exploratory, playful, and “pure,” in the sense of being unedited or digitally manipulated.4 The four-minute-long About Flowers, which begins with handwritten intertitles, takes a “bee’s-eye view” of a flower bouquet. Woodbury’s camera pushes in on the stamen of a bloom as she passionately narrates the recent findings from her biology class, moving between flower to flower and pointing things out as she goes along. I asked Woodbury, who is now 30, what it was like to make films at such a young age. Although her memory of that time is fuzzy, she tells me that she feels surprised at people's responses, and “wouldn't have expected the film to stand up when evaluated alongside more experienced and intentional filmmaking.” She also found it extremely funny to rewatch today: “I love how earnest and grown-up I was trying to be, especially amid the chaos of the camera work and overconfident narration.”

Rubi Qi Tondelli, age four. Photograph by Reno Tondelli.

CHILDREN SHOOT MOVIES ON SMARTPHONES

There’s never been a better time for children to be making films, thanks to the availability of smartphones, consumer nonlinear editing applications like iMovie, and the ease of distribution on social media and elsewhere. Many babies are smartphone adepts. They have been known to produce minute-long videos of tables, ceilings, and their parents’ chins. I have chosen to read this as an open declaration of creative intent.

Brooklynn Prince, who was only six years old when she starred in Sean Baker’s The Florida Project (2017), announced her first film, Colors (2019), two years later on her Instagram: “My dream of directing started on The Florida Project. I loved watching Sean work and was inspired by his patience, vision, and creativity. Since then my dream was to become one of the youngest directors of all time. Today my journey as a director begins.” The resulting film, which premiered at Cannes Film Festival, was distributed via the Curated by Facebook platform, pointing to the role global corporations play in “mediating and disseminating children’s culture.”5 A charmingly intimate tale of a young friendship, Colors takes an impressionistic look at the highs and lows of youth. The vertical frame and merry-go-round camera movement captures the giddiness of childhood play in the rain, while the saturated palette evokes the high-key color of children’s toys, with echoes of Baker’s work. There is darkness there as well, a morbidity and fatalism in which the young are extremely well-versed.

The Guinness World Record for the youngest-ever director of a professionally made feature film is currently held by a seven-year-old Nepalese film-maker named Saugat Bista. His film Love You Baba (2014) is a romantic drama about a single father taking care of his young daughter. It was shot in just under a month across several locations in Nepal. “I thought my son was joking when he first told me that he wanted to direct a movie,” Saugat's father, Gajit Bista, said in an interview. “But when he showed intense interest to become a professional director, I gave him all my support.” Indeed, Gajit wrote the screenplay and starred in the film. Parental assistance notwithstanding, Saugat is definitely not messing around, as we see in footage of the shoot: he commands a large group of adults, positions his actors carefully in the scene, and talks animatedly about his creative project.

CHILDREN MAKE MOVIES BEHIND YOUR BACK

Children are known to make movies on the sly, when the adults have their backs turned. The American underground filmmaker Kenneth Anger started filming when he was ten years old using surplus reels from his family’s home movies. He shot his first surviving film, Fireworks (1947), while his parents were away for a long weekend. An explosive work of Freudian dream logic, sexual violence, and gay desire, Fireworks represented everything Anger had “to say about being 17, the United States Navy, American Christmas and the Fourth of July.”6 Although he says he was seventeen when he shot it, several biographers have suggested he was more like 20. What could be more adolescent than lying about your age?

Making a film while your guardians are away is the narrative premise behind The Day My Aunt was Ill (1996), a punky video piece by the Iranian filmmaker Hana Makhmalbaf. The youngest daughter of filmmakers Mohsen Makhmalbaf and Marziyeh Meshkini, Hana made the film at eight years old using the family Sony Handycam. It opens with a group of children drawing with chalk on the pavement under the semi-watchful eyes of their grandfather. (Their aunt has gone to get a nose job.) When the grandfather asks them to return to the house, he lures them by offering his bald head as a canvas to continue painting. But that clearly isn’t enough: the film jumps to them in the middle of making a movie, where we see them debating their roles and arguing over who is more important. One of the girls breaks down in tears. “This movie is about envy,” we are told early on in the film. “We wish to show how kids envy each other.” The film comes to an abrupt end when the director declares that she needs to go to the toilet. There is no better way of wrapping a movie than with a ceremonious restroom break.

The Day My Aunt Was Ill (Hana Makhmalbaf, 1996).

STOP PROJECTING AND LET THE KIDS PROJECT

Even as children make their own movies, we continue making movies about them. Alice Guy-Blaché’s lost film, The Cabbage Fairy (1896), considered the first narrative film, delights in the magic of pulling a small baby from cabbage leaves, and we’ve been at it ever since. There is something about the untapped potential of childhood that brings out a filmmaker’s most extractive impulses. In today’s smartphone surveillance society, the desire to capture raw childhood experience is ever more acute. A new term, sharenting, has even been coined to describe a phenomenon which many parents (myself included) are “guilty” of engaging in when they post pictures or videos of their non-consenting children on social media. In March 2024, a French law was passed to enhance the protection of children’s rights online.

American experimental filmmaker Stan Brakhage—progenitor to today’s sharenting culture—famously celebrated the visionary potential of the prelingual child in an oft-quoted section of his manifesto, Metaphors of Vision (1963). True vision, he writes, “seems inherent in the infant's eye, an eye which reflects the loss of innocence more eloquently than any other human feature, an eye which soon learns to classify sights, an eye which mirrors the movement of the individual toward death by its increasing inability to see.”7 Brakhage was not alone in essentializing children’s vision and elevating it to the driving force of a new art. For the Romantics, the Surrealists, and the hippies, childhood was a blank canvas on which to project ideas of prelapsarian innocence: a youthful vision unclouded by prejudice or social norms. At its worst, this nostalgic celebration of youth slips into invoking a return to the “good ol’ days” before industrialization (and the sharp decline in infant mortality rates). The great myth of childhood innocence endures today, even as it is repeatedly undone by war and violence, which, as Ara Osterweil reminds us, “transforms children into witnesses, participants, and casualties.”

Hausu (Nobuhiko Obayashi, 1977).

In my admittedly limited experience, children are stronger poets of the mundane and the scatological than they are of the visionary. Which is not to say that they don’t have good ideas. They have great ones. For his first feature, director Nobuhiko Obayashi asked his ten-year-old daughter Chigumi to tell him about her nightmares, and ended up crediting her as cowriter of his debut feature, the psychedelic haunted-house horror Hausu (1977). From child-gobbling pianos to spooky cats, Hausu bears the hallmarks of a child’s overactive imagination spun into middle-of-the-night overdrive.

By elevating childhood precocity, we run the risk of placing undue adult burdens on the simple act of creating. We fetishize youth as a unique selling proposition in the ever thirsty marketplace of novelty, when precocity is a privilege not available to everyone. But pride in a child’s work also comes with the territory of parenting. Though in my eyes it is a masterpiece, my own child’s artwork may not be better than another’s. It might even be worse.

Laurent Schwarz is a two-year-old toddler from Bavaria who has been dubbed the “pint-sized Picasso.” His colorful abstract paintings, which he executes with his fingers, sell for thousands of dollars to international collectors and galleries. ‘It’s totally up to him when and what he paints,’ his mother tells the Sunday Times. “Sometimes he doesn’t feel like painting and doesn’t set foot in his studio for three or four weeks but then suddenly it grabs him and he says, ‘Mama, painting.’”

Children Make Movies (DeeDee Halleck, 1961).

Something good seems to happen when we abandon individualist notions of youthful prodigy and focus instead on collective forms of artmaking. Filmmaking workshops for children, which have been taking place since at least the 1960s, point a way forward. Providing young people, often from disadvantaged backgrounds, with access to tools and technical instruction alongside a willing team of conspirators, these classes can bring cinema to the places that need it the most.

The film that inspired this feature, Children Make Movies (1961), follows a filmmaking workshop led by the community media activist and champion of children’s filmmaking, DeeDee Halleck. Held at the Lillian Wald Recreation Rooms in New York’s Lower East Side, the classes have children scratching directly onto celluloid, an accessible form of animation that can bring out anyone’s inner abstract expressionist. Halleck also screens Norman McLaren’s anti-war film Neighbors (1952), which the pupils use as inspiration for a filmic reenactment. As they build a tower, the boys fight to the death over its construction, while the girls look on, bemused by the fallout. Meshing together process and product, Children Make Movies incorporates the children’s own scratch film and live-action remake, the latter taking an incisive look at the gendered nature of war.

Why are we surprised when children prove themselves, time and again, to be informed and passionate political subjects? In Ignacio Agüero’s One Hundred Children Waiting for a Train (1988), which documents a weekend film workshop in a poverty-stricken, rural shantytown in Santiago, the kids make it abundantly clear that they want to make a film about labor strikes. Their teacher, Alicia Vega, gets the cogs whirring by putting flip-books and optical toys like thaumatropes into the smallest of hands. She invites her students to dream, an activity little prioritized in the poorest parts of Pinochet’s Chile. And then they go to the cinema for the very first time. What happens after? A lot of that will depend on matters of class, economics, resources, and access. But if anyone can make and remake the world, it is children. They are the ones inheriting this mess, after all.

- Kim Masters, “Auteur of Adolescence,” Washington Post (1992). ↩

- William J. Hawkins, “Kidcorder,” Popular Science (August 1987), 59. ↩

- Spielberg himself directed his first film, Escape to Nowhere (1961) aged only fourteen. ↩

- Andrea Nina McCarty, “Toying with obsolescence: Pixelvision filmmakers and the Fisher Price PXL 2000 camera,” PhD dissertation, Massachusetts Institute of Technology (2005), p. 132. ↩

- Noel Brown, Introduction, in The Oxford Handbook to Children’s Film, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2022, p. 17. ↩

- Quoted in Wheeler Winston Dixon, The Exploding Eye: A Re-visionary History of 1960s American Experimental Cinema (State University of New York Press, 1997), 9. ↩

- Stan Brakhage, Metaphors on Vision (Film Culture, 1963), unpaginated. ↩

![White Paper Games Announces Psychological Thriller ‘I Am Ripper’ [Trailer]](https://bloody-disgusting.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/iamripper.jpg)

.png?format=1500w#)

![It All Adds Up [FOUR CORNERS]](https://jonathanrosenbaum.net/wp-content/uploads/2010/08/fourcorners.jpg)

-Pokemon-GO---Official-Gigantamax-Pokemon-Trailer-00-02-12.png?width=1920&height=1920&fit=bounds&quality=70&format=jpg&auto=webp#)