“It is a Kingdom of Conscience or Nothing”: Ridley Scott’s Kingdom of Heaven at 20

20 years ago, 20th Century Fox began the summer-blockbuster season with a sword-and-sandals epic about the Crusades. Kingdom of Heaven‘s pedigree was impressive, if not bulletproof. Ridley Scott was only five years on from his Best Picture-winning Gladiator (not to mention immediate hit follow-ups Hannibal and Black Hawk Down, both in 2001) and newly minted […] The post “It is a Kingdom of Conscience or Nothing”: Ridley Scott’s Kingdom of Heaven at 20 first appeared on The Film Stage.

20 years ago, 20th Century Fox began the summer-blockbuster season with a sword-and-sandals epic about the Crusades. Kingdom of Heaven‘s pedigree was impressive, if not bulletproof. Ridley Scott was only five years on from his Best Picture-winning Gladiator (not to mention immediate hit follow-ups Hannibal and Black Hawk Down, both in 2001) and newly minted movie star Orlando Bloom had plum, stand-out roles in two successful franchises (one of which had just won Best Picture itself). Still, it was a risky endeavor. Even riskier when considering the filmmakers’ challenging of religious truths and customs at a time when many had allowed fear to give way to hate, using their faith as a rationalization for terrible sins.

The film tells of the blacksmith Balian (Bloom), a tortured soul reeling from the death of his wife and infant child. His father, Baron Godfrey (Liam Neeson), and legion of crusading knights arrive to invite him to travel with them to the Holy Land. Though he initially refuses, Balian joins after committing murder in an act of vengeance. A flawed sinner wracked with tragedy and guilt, he goes to Jerusalem in search of something resembling God. He does not find it; what he does find is conspiracy and conflict. He is thrust into the middle of a struggle for power as the righteous King Baldwin IV of Jerusalem (Edward Norton) dies from leprosy. The evil Guy de Lusignan (Marton Csokas), married to the king’s sister Sibylla (Eva Green), makes a play for the throne, determined to kill every Muslim he can and break the tenuous peace of the last few years in the region. It all culminates at the Siege of Jerusalem, wherein Balian faces off against Saladin.

Fox and Scott alike balked at the three-hour-plus cut after subpar test screenings, something the director regrets. (“This is the one that should have gone out,” he said upon the release of the 45-minute-longer director’s cut.) Even in the bastardized edition that was ultimately released in theaters on May 6th, 2005, one of the most sympathetic characters is Salah ad-Din Yusuf ibn Ayyub, commonly known as Saladin (Ghassan Massoud). He was the sultan of both Egypt and Syria and the military leader of the Muslims during the Third Crusade. Weeks before the film’s release, Scott wrote a column for The Guardian wherein he states:

“I wanted people to see events from the Muslims’ point of view as well, and the way to do that was to develop strong, multidimensional characters on that side. Especially Saladin, as played by Ghassan Massoud, a wonderful Syrian actor. I felt it was important to use Muslim actors to play Muslim characters. You see Saladin in private moments; you see his leadership, how he tries to keep the peace. He was under pressure from his people, and on the other side there was the radical faction of the Templars and other knights—what we might call the right wing or Christian fundamentalists of their day. He is a man with a strong sense of his destiny.”

Those fundamentalists were not happy with the film, and reviews in general were tepid at best. The United States was in the middle of both the Iraq and Afghanistan War. 9/11 was barely three-and-a-half years in the past, and a marked increase in “discrimination against Muslims, Sikhs, and persons of Arab and South-Asian descent” was undeniable. A blockbuster underlining any sympathetic view of Muslims was an unappealing prospect for many Americans in 2005. There is also screenwriter William Monahan’s bold choice to tell a story about a knight who refuses the call and continues to refuse the call throughout the picture. “Refusal of the call,” as far as Joseph Campbell’s “Hero’s Journey” is concerned, is meant to be a stepping stone to the rest of the adventure. Here, Balian’s growth leads him to tolerance and some sort of Agnosticism; in the climax, he surrenders Jerusalem to Saladin in order to guarantee his people’s safety. By the end of the film’s domestic box-office run, it had grossed less than $50 million on a budget of over $100 million. While Kingdom of Heaven performed better internationally, it was a flop.

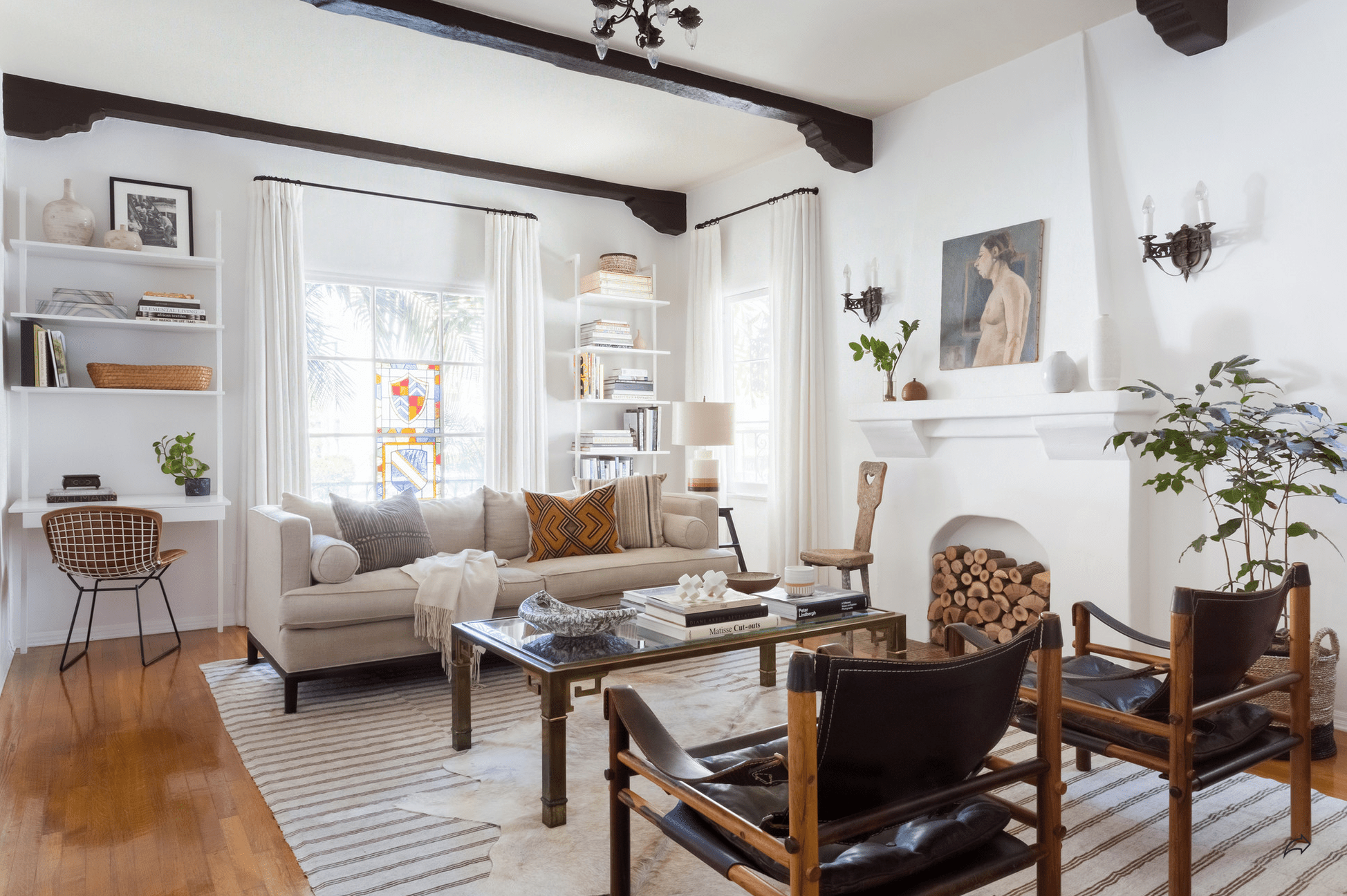

Behind the scenes of Kingdom of Heaven

In a recent, superb interview with Roxana Hadadi, co-star Alexander Siddig speaks to the theatrical cut’s failure contra Kingdom‘s eventual, extended edition:

“It’s way better than the first cut. The first cut got panned by the critics, and the person who suffered was Orlando, because they thought he was just rubbish as a lead. But had they understood what was happening, and why his character was kind of failing upwards, and how he didn’t really know why he was there and he was just a little boy, if they understood that about it, they would not be looking for Mel Gibson. They would be going, ‘Oh, this is a much more interesting take.’ Orlando, I don’t think he really recovered from it.”

Bloom’s career as a leading man certainly didn’t. Cameron Crowe’s Elizabethtown was ridiculed out of theaters only months later, followed by a couple of successful Pirates of the Caribbean sequels the next two years, for which Bloom did not get much credit. After that, he quite deftly reformed into a reliable character actor, both funny and dramatic as needed. Eva Green’s Sibylla character arguably suffered even more from edits, something Scott mentions directly in his introduction to the director’s cut. Nevertheless, it is heartening how kind time has been to the proper version. As Hadadi notes in her piece, Kingdom of Heaven‘s upcoming 4K SteelBook release is already sold-out. There’s also a one-night-only 4K theatrical re-release scheduled for May 14, 2025.

Scott’s complicated, clear-eyed observation of faith in Kingdom of Heaven––its deft encapsulation of religion in all of its altruism and hypocrisy––speaks directly to my own struggles as a forever-lapsing Catholic: to have been raised within the strict system of the Church, wherein the promise of eternal life is tied directly to obeying a convoluted, outdated set of rules and regulations that dismisses many out-of-hand, and then to be told by that same Church that forgiveness is also immediately available to all. Absolution is merely a confessional away. Just be careful not to sin again. And be extra-careful not to be gay, or bisexual, or sympathetic to a woman’s freedom of choice. Hell is sitting there, waiting for you to make a mistake.

But then, this too is written in the Bible: “Indeed, there is no one on earth who is righteous, no one who does what is right and never sins” (Ecclesiastes 7:20). There’s also this: “When you give a banquet, invite the poor, the crippled, the lame, the blind, and you will be blessed. Although they cannot repay you, you will be repaid at the resurrection of the righteous” (Luke 13:14). The same belief system that preaches “All Are Welcome” alienates so many. It’s confusing to grasp as a child, and no less confusing as an adult.

In Scott’s film, the phrase “God wills it” is used as a band-aid to cover all manner of sin on either side of the battlefront––Catholic or Muslim, no matter. As Balian and his crusaders begin to falter during the climactic siege, the priest with them proposes they all convert to Islam to survive and “repent later.” Balian cannot conceal his contempt of the man. In his speech to his people, he asks:

“What is Jerusalem? Your holy places lie over the Jewish temple that the Romans pulled down. The Muslim places of worship lie over yours. Which is more holy? The wall? The Mosque? The Sepulcher? Who has claim? No one has claim. All have claim!”

Earlier in the film, when faced with the opportunity to steal the crown by simply letting the royal court order Guy de Lusignan’s assassination and marry Sibylla, Balian refuses. “It is a kingdom of conscience or nothing,” he says. Conscience by definition means “a faculty, power, or principle enjoining good acts.” Monahan and Scott are preaching that every one of us knows what is the right thing to do. That faith in its best form is trust in oneself to do what is right. That religion in its best form is simply The Golden Rule: treat others as you would like to be treated. Kingdom of Heaven distills this quite simply within its epic construct. What would it cost us to be good, to be accepting? Nothing. Everything.

The post “It is a Kingdom of Conscience or Nothing”: Ridley Scott’s Kingdom of Heaven at 20 first appeared on The Film Stage.

![Hollow Rendition [on SLEEPY HOLLOW]](https://jonathanrosenbaum.net/wp-content/uploads/2010/03/sleepy-hollow32.jpg)

![It All Adds Up [FOUR CORNERS]](https://jonathanrosenbaum.net/wp-content/uploads/2010/08/fourcorners.jpg)

![Amex Cardholders Can Now Earn Up to 40K Points Per Referral [YMMV]](https://boardingarea.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/b63b2549a66603e627b2c3522bb2d8ad.jpg?#)