Scriptnotes, Episode 684: Landing a Series with Eric Kripke, Transcript

The original post for this episode can be found here. John August: Hey, this is John. Today’s episode has even a little bit more swearing than usual, so standard warning about that. [music] John: Hello, and welcome. My name is John August, and you’re listening to Scriptnotes, a podcast about screenwriting, and things that are […] The post Scriptnotes, Episode 684: Landing a Series with Eric Kripke, Transcript first appeared on John August.

The original post for this episode can be found here.

John August: Hey, this is John. Today’s episode has even a little bit more swearing than usual, so standard warning about that.

[music]

John: Hello, and welcome. My name is John August, and you’re listening to Scriptnotes, a podcast about screenwriting, and things that are interesting to screenwriters.

Today on the show, how do you plan for a multi-season TV series, and how do you wrap it up at the end? Our guest today is the creator and showrunner of shows such as Supernatural, Revolution, Timeless, Gen V, and of course, The Boys, which is back for its final season. Welcome, Eric Kripke.

Eric Kripke: Hey, thanks, John. Thrilled to be here.

John: Now, the fourth season of The Boys premiered last June, but you are now working on the fifth and final season, so I want to talk to you about that, but I’d also love to get more granular on the process of developing a show, breaking scripts, and seasons. We also have listener questions on bottle episodes, and using the conventions of comic books.

In our bonus segment for premium members, let’s talk about blood, because you use an astonishing amount of blood on The Boys and Gen V. I’d love to discuss what you’ve learned about blood on the page, and blood in practice.

Eric: Amazing, I’m in for all of that.

John: Before we get into the details on how shows work on the inside, can we talk a little bit about your background here? Because how early in your development did you know that you wanted to do television versus features? What’s the backstory? Pitch us, Eric Kripke.

Eric: [chuckles] I was raised in Toledo, Ohio. I was one of those kids, I think it was E.T. in ’83. I was nine, and I came home from E.T. and told my mom, “Did somebody make that?” She said, “Yes.” I said, “Well, then that’s what I want to do.” I was like the very prototypical ‘80s Spielberg obsessed, that particular subspecies of kid.

John: There’s a lot of us in that age range who are like, those were the important movies. The Spielberg movies were the ones like, “Oh my gosh, that is the vision I have,” or that’s how you get the J.J. Abrams emulating that model.

Eric: Yes, and it’s so funny looking back how few of them he actually wrote, or directed. You look back, and you’re like, “Well, that was actually Richard Donner, and that was actually Joe Dante, and that was actually Tobe Hooper,” with apparently, a very heavy assist from Spielberg, according to legend. It’s funny when you’re like– Oh, he was just– I mean, producing is a big job, obviously, but those weren’t actually his movies.

Anyway, it was just fascinating to me. I was that kid. I’d say by the time I was 11, I wanted to go to the USC Film School, because it was the only film school whose name makes its way back to Toledo, Ohio. I found the short story that I wanted my senior thesis movie to be when I was 13 in a Twilight Zone magazine written by Richard Matheson, and I carried it around with me in wrapped plastic.

I took it with me to camp and college, and anyway, and cut forward, and I went to USC, and I made that movie my senior year, and my goal was to be a director for features, and feature comedies. I made short films, and was unemployed, the usual thing. Then, my shorts were in Sundance and Slamdance at the same year, and then we won Slamdance, and okay, now I have an agent, and now I’m able to pick up bad open writing assignments, which they were giving away a lot more candy back then than they are today.

John: Let me pause you for one second, because we have a link here to Battle of the Sexes, which was a short film that you got into Sundance. Was that also at Slamdance?

Eric: Another one, Truly Committed, was at Slamdance, but Battle of the Sexes was at Sundance, yes.

John: I look at the short, it’s like, “Oh, well, I can see this is a person who wants to be a director, and wants to make a certain kind of movie,” because it’s a very well-executed, single-premise conceit just like–

Eric: Oh, I’m thrilled and stunned that you watched it, but, yes.

John: It’s six minutes, so it’s not a huge burden on anyone’s time, but it was a very good calling card for that specific kind of director who wants to do a thing. Rawson Thurber, who was my assistant, he also made a short film coming out of the USC program, but then a second short film, which was Terry Tate: Office Linebacker, which kicked him off in his career. It’s a good way to announce yourself to the town, and was that the intention behind these short films is to land yourself representation?

Eric: Yes, the main thing, and I know Rawson, he’s a great guy. The main thing at the time was make a short film, and have the feature-length version of that film as a script ready to go, and that’s the best way to get yourself into the director’s chair at a young age while you’re in your 20s. That was sort of the– That’s what you do.

John: Was the intention for Battle of the Sexes, here’s the short, and did you have a screenplay that went along with it?

Eric: I did. There’s a Battle of the Sexes feature-length screenplay that is only moderately successful, and I took it out. I got an agent, I had a good short film, people wanted to have meetings. I took out that script, and every single person who read it was like, “Yeah, no, what other scripts do you have?” I had nothing, [chuckles] so I totally blew my moment.

I had that month where I was taking eight meetings a week, and nobody liked the script, because it is a very sloppy script. I had to really learn writing from doing it. I don’t feel like I was an innately gifted writer. I always felt I was better at filmmaking.

John: Let’s talk about the difference between, so something like Battle of the Sexes is essentially a sketch. It’s something that, it’s a long version of what could be a Saturday Night Live sketch.

Eric: Yes.

John: We’ve had a couple of writers on the show to talk about the difference between sketch writing and writing the longer projects, pilot writing, a feature for sure, is that there’s a sense of ongoing development. It’s not just a complication upon the premise, it’s really a journey that the characters go on, and that’s not a natural progression sometimes from the sketch forward. It’s a very different thing.

We had Simon Rich on, and we were talking about, he writes short stories and sketches that are short and tight, and deliver the payload that they’re expecting for that small form, but it’s not what a feature script does. It’s not what a pilot does. It’s not setting up a whole world, which you end up having to learn how to do. How did you learn how to go from this, and the script that wasn’t working, to Supernatural, or other shows you were writing?

Eric: Through failure. I really feel that I learned what to do through process of elimination. I failed every other way until I figured out, “Oh, this actually works. This gets a response.” Everyone has their own process, but for me, what really landed was two things. Everyone says character-driven, but almost nobody means it, and because you have to walk the walk, and what I learned was, the stories were hanging together better when I started with, “Okay, who’s this person, and what do they want? Where do they start, and where do they end?

Then, okay, what are the steps that get them there? Psychologically, why do they feel that way? Then, okay, now, at least for TV, and okay, now what’s the plot that illuminates those beats?” It wasn’t until I landed there that things started to cook. Then, the second one was, which I think is a mistake a lot of young writers make, and you know maybe better than anybody with the stuff you’ve written, but you just have to be so brutal with your internal logic, and you have to be air-fucking-tight.

The Battle of the Sexes script, for example, failed because it was sloppy world-building. I set up rules in the beginning that were not consistent through the end, and you really have to look at it as, does this particular beat, does this particular line, does this particular reference fit in the rules of the world you’ve created? If they do not, you have to get rid of them. I don’t care how good that line, or character, or moment is. It’s a cancer to the credibility of the world you’re trying to create.

John: Let’s pull this back. Battle of the Sexes, for people who haven’t watched the little short film yet, the premise is that, when women go off to the restroom, they’re actually entering into a secret lab where they can do deep forensics on the man that they’re talking with, and figure out whether they should continue the conversation, or pull away from the conversation. It’s incredibly heightened.

It’s incredibly, a Mission Impossible level of stuff happens inside that space. In a sketch, it’s funny that we buy it because, the world expectations are not so high. I can imagine in the course of a feature-length film, or if this was the premise to a TV show, building that up, so the rest of the world actually made sense would be challenging.

Eric: Yes. It might be doomed from the beginning, and the first 20, 25 pages of that script are the best, and then it falls apart. It’s like, this idea of a guy who’s chasing a girl, and the obstacle is this secret network of women that are all in communication with each other to secretly run the world. By the way, not wildly different than Angelina Jolie’s agency in Mr. & Mrs. Smith. Not that different, but by the end, it became every woman on the planet, and it was just too big. It should have just been a woman spy, spying for her– It should have been Mr. & Mrs. Smith.

That’s the best version of this idea. In the way that Brad Pitt has Vince Vaughn, and he’s riding around in a dune buggy, and she’s very fastidious and neat. Those are the right energies, but it was contained. I didn’t understand containment, and I didn’t understand the logic exercise, where you have to take everything to its nth degree and say, “If that exists, then that means this, this, this, and this, and is that okay for your story?”

Obviously, every woman involved in a conspiracy, [chuckles] raises way too many problems. The entire thing, look, I was 25 when I wrote it, but everything just melted by the end of that. Everyone who read it was like, “It really started promising, and then it went off the rails, and never went back on.” [chuckles]

John: Just very honest with you.

Eric: [chuckles] Yes.

John: Talking about the steps of learning between that, and something like a Supernatural, were you staffed on other TV shows, were you getting other deals to do stuff, what was happening?

Eric: I mostly blew my moment of getting any sort of feature directing going. Then, I took a couple open writing assignments for comedies, because I thought I was going to be a comedy filmmaker. They were all horrible scripts. They never got made, and I was banging around for three years, just being one of those guys who never gets anything made, and just that Twilight Zone.

I read one of the scripts, and it’s like, you can see someone’s struggling to learn something, but it’s terrible. They were terrible. It turns out, I wanted to be a comedy writer, but turns out I sucked at it, plus, the tyranny of multiple jokes per page, just was something that I just couldn’t do. I just was really bad at– The people that are good at it, are so good and every other line is a killer. I couldn’t do that. I needed more build up. I just didn’t have that muscle.

Then, my agent was like, “Why don’t you take a TV meeting?” This was 2002. TV then is not what TV is now. TV then, my film school friends were like, “Oh, you’re going to go do TV. Good luck, good luck. I always saw you as a TV person,” and I’m like, “Fuck you.” [laughter]

That was the vibe. I went to take a TV meeting. They liked Battle of the Sexes. Here’s something that’ll also tell you how different the time was. I was a 27-year-old kid. I walked into that meeting based on Battle of the Sexes alone, they offered me the Wonder Woman series-

John: Oh, my.

Eric: -and I passed.

John: Incredible.

Eric: I said, “Yes, Wonder Woman’s not really my thing. No, pass.” Just shows you how different IP was then, but then they said, “Would you be interested in writing a pilot?” I tried, and I wrote a pilot, and it didn’t go anywhere, but they liked it. Then, my break was, they were trying– Smallville was a big deal on the WB.

John: Friends of mine who’ve been on the show, Al and Miles, they created Smallville. They were also out of USC, and I felt like, “Oh, is it sad that you’re doing TV?” No, it was a giant hit.

Eric: Exactly. Anyway, but at the time, and this show was– The story I’m about to tell is about a huge failure, is they were trying to recreate it with Tarzan, and they couldn’t break Tarzan. They couldn’t figure it out. They had big writers, and it’s a big title. I said, “Let me take a crack at it.” I had the winning pitch, and then I wrote a script and they loved the script. Then, I have David Nutter shooting my pilot, all of this–[crosstalk]

John: David Nutter is a giant TV director. He’s who you want to do your pilot.

Eric: The winningest pilot director in TV history in terms of more pilots picked up, and such a lovely guy. He makes the show, the show’s good. They pick it up to series, and suddenly, they partnered me with somebody, but suddenly, I’m a co-showrunner of a TV show at 28-years-old, having never stepped into a writers’ room before.

John: Eric Kripke, I was in the same situation as a 28-year-old creator of a TV show for the WB Network, and I had a nervous breakdown. I completely melted down. I’m seeing here your show lasted eight episodes, mine last was six.

Eric: Wait, what was your show?

John: I did the show D.C. I was partnering up with Dick Wolf.

Eric: Oh, right. Yes, young people in D.C. and making it happen. I totally remember that.

John: Yes. It was a post-Felicity show. It was a good premise. It sold well, and I was excited to be doing it, and I just was completely out of my depth in the process. Were you partnered up with somebody who actually knew what they were doing? What was that situation?

Eric: Yes. This writer named P.K. Simonds who had ran Party of Five. We’re still friends to this day. He’s such a lovely, lovely dude. I was partnered with him. He encouraged me to try to make it creatively my own. He wasn’t interested in taking it over. He wanted me to realize whatever my vision was. I proceeded to make so many mistakes, every mistake. I worked with, and I’m sure you did too. I worked with John Levesque. Did you work with John?

John: The whole thing is a blur to me. Literally, I can picture myself serving as third person going through a situation that I wasn’t actually present for.

Eric: [chuckles] He was this infamously hard executive at the WB. To just give you one quick example of him. You’re just a kid and they don’t teach you politics. He calls me on day one, or he takes me to lunch on day one of the job, and he’s like, “Look, here’s what’s going to happen. You’re going to slip me outlines and scripts before you show them to the studio. I’m going to give you the notes. You’re going to revise them, and then you’re going to show it to the studio, who’s then going to show it to me, and I’m going to pretend to love it. That’s how this is going to fucking go. Do you understand me?” I was like, “Yes, sir?”

I was immediately immersed in espionage, and slipping scripts. Then, Laura Ziskin, who was the producer of it, found out, and she was angry at me, but I didn’t understand. It was just a disaster. By the way, Tarzan shouldn’t be a TV show. [chuckles] It was doomed from the start.

John: I want to time travel back to you and tell you that, because also I did the Tarzan movie for Warners.

Eric: Oh, my.

John: It’s a very difficult character to center a story around in a feature, but as a TV show, dear Lord, you have a central character who we want to see shirtless, but can’t be shirtless all the time, obviously. Someone who’s by definition, low verbal, which makes things really challenging. It’s just–

Eric: It’s a mess. What I got handed was, “We want Tarzan in New York. You have to make Tarzan in New York work. Okay?”

John: It’s a jungle out there.

Eric: Right. [chuckles] Exactly. I think that was literally the tagline.

John: I’m sure it was, yes.

Eric: My take was, make the show about Jane. She’s a cop and whatever, but I’m like, “There’s a character you can relate to.” It’s like, Beauty and the Beast. It’s like, this guy comes in then he saves her–

John: Sleepy Hollow is a similar dynamic.

Eric: Then, we cast Travis Fimmel, who went on to be pretty big in Vikings. It was just nothing, but raw charisma. We cast him as Tarzan. He was a Calvin Klein model at the time, it was his first job. He’s just got that thing, and so all the dials went to the right whenever he showed up on screen, the testing dials. So all the executives were like, “He’s the show.” I’m like, “No, he’s a monkey. There’s nothing. He doesn’t know– Maybe he gets a job. How about one episode where he gets a job?”

I’m like, “He doesn’t know what currency is. There’s just nothing you can do, except that he loves this girl, and he wants to protect her.” Anyway, it was a disaster.

John: It was a mess. Let’s fast forward up to Supernatural, which was not a mess, which was a tremendous success. Tell us about the process of figuring out how to do Supernatural, not just what the premise was, but it feels like you approached that show with an idea of what that was going to be week-to-week in a very smart way.

It wasn’t just like, “Here’s the pilot, then we’ll see what happens.” You very much knew this is how the show wants to tell itself week-after-week. This is a central relationship. This is the kind of thing that happens in an episode. Was that clear from the very first pitch?

Eric: No. Here’s what was clear, which was one of the many lessons I walked out of Tarzan from, was, if you’re going to make a network show, and do 22 of them, spend most of your time thinking about the engine, and what’s going to give you story every week that you can always go back to that well if you need to. I happen to have been obsessed with Urban Legend. I still am.

I like to collect them, and study them and did in college. For me, the engine was, “Okay, characters are investigating urban legends that all turn out to be real.” That was the premise. I pitched a journalist. I pitched a bad rip-off of Kolchak, where he worked for a tabloid, and he was investigating. I had a whole pitch, and Warner Brothers, I pitched it to them, Susan Rovner. She said, “I really liked the urban legend idea, but the reporter thing’s really boring. What else have you got?”

John: Yes.

Eric: I had written in my notebook, literally the day before, only two lines. I wrote, “One way you could do this story would be Route 66.” I said, “Well, I have a whole other version of this idea.” I’m like, “It’s Route 66 and it’s these two guys, and they’re in a cool car, and they’re driving around the country.” Then, on the spot said, “They’re brothers.” I don’t– Still don’t know why. Where it came from.

She started leaning forward. She’s like, “Ooh, a sibling relationship, and a show about family. Oh, I’m really interested.” I’m like, “Great. I have all those notes at home. Give me a week to just go home and get them. Then, I’ll come back.” I went back and I furiously wrote what ultimately became the pilot pitch of Supernatural. The way I really– It’s funny. It’s like, thank God for those urban legends, because that’s how I learned structure.

They’re such tight little jokes, really. To take these two characters, and put them into those stories, provided a structure that I really learned a lot about. A beginning, a middle, a twist, and an end, because I always had that to go back to. I very much learned how to write on the fly.

John: Can we talk about Supernatural? Because it was a classic broadcast WB Network show with commercial breaks. I’m assuming that, as you’re writing the pilot, at every given episode, you’re really writing towards those act breaks. Those are the key moments of reversal that you’re hanging your story on those points, and then figuring out how to get to those points in between.

That probably starts in the blue sky of the episode. Then, those are the moments you’re listing on the whiteboard. Is that a five-act show? Is it a six-act show? I don’t know what it was at that point.

Eric: We started at four plus a teaser, and then they added another commercial break. Then, after season two or three, it was five plus a teaser. Six acts, yes. In a 45-page script.

John: Yes, so it’s really, you’re racing between those moments. Once you accept that, and you can build off that, and crucially, once you have a show that can actually fit that structure, it’s liberating. It’s got to go be just so nice.

Eric: I loved it, and I have to tell you, I miss it in this new streaming, freeform thing. The discipline of having something awesome happen every eight pages, is a really smart discipline. It’s very, I think, instructive because you just– To this day, I live in absolute terror of being boring, because I hate the idea of going more than 10 minutes in anything without someone saying, “Oh shit, that’s crazy,” because I had to do that, because I needed you to come back after the deodorant commercial.

Having too much structure was really great training ground, that then you can pull back a little bit. I’d say for The Boys now, we write three-act structure, but we are still really interested in structure. Structure saved my life. It’s how I learned to do this. Once you realized, “Oh, this is all just math.” It’s all plant, pay off, three or four character beats, set up, twist, action, wrap up.

Once you realize it’s all just beats that then you just blend together, and then hide under dialogue, and action, and emotion, and sex, and love, but the mechanics of it, the erector set, infrastructure of it is really predictable. That saved my life, because I was like, “Oh, okay.” To this day, I care more about structure than anything, because I think it’s like a life preserver for me.

The people who write independent shit, that they’re just like, “Oh, no, I hate structure. I just want– It’s a day in New York.” That terrifies me. I don’t know how to do that. I only know how to do, here are the four beats, and here’s how we’re going to get from A to B.

John: Structure classically being, when things happen. This is, as you’re moving through forward in time, these are the things we’re going to encounter. The structure of television also necessarily implies a structure of where things are going to happen. Supernatural is a road show, but they happen to be just driving around the same places all the time. It’s convenient that way.

With The Boys, it’s been interesting to notice season-by-season, figuring out like, “Oh, what are your standing sets? What are the places we’re going to come back to?” Because for financial reasons, but also for narrative reasons, we need to have home bases from which people can move out. There’s this last season, or maybe the season before, we have this office building with windows all around it, that it’s like, that’s a central set.

We know we’re going to come back to this place. It’s a home base for the production, but also for the viewer to say like, “Okay, I understand where we’re at. We’ve come back around, and these things have changed since the last time we were in this space.”

Eric: Yes. No, The Boys is actually the first show that I’ve ever done that isn’t some version of a roadshow. Standing sets were actually pretty new to me, and they’re very useful. Look, I have to say, I find them more useful logistically, budgetarily as a producer, than I find them necessarily narratively useful. Just today, we’re trying to bring down a budget of one of our episodes, and we’re like, “Well, let’s move these three scenes onto our home sets, and then we don’t have to drive out, or build them or whatever.” To me, that’s the value of home sets.

I don’t find myself watching something, and wishing that character went to that home set. I’d rather they didn’t. I like the variety life, that cinematic thing where everything is different and beautiful, and there’s a variety, is my own personal taste. You do need them, and they have saved my ass on numerous occasions.

John: You’ve mentioned that Boys, you think of it as being three acts, four acts. As you’re breaking an episode, what is the process? How many people do you have in the room? You probably started the season with a sketch of an idea of where things were headed. That came down into, these are the episodes. When you’re actually focusing on an episode, how many beats are you looking for? When do you have enough and not too much for an episode, and that someone can go off and start working on script?

Eric: We start– There’s about seven of us, seven plus me. Everybody gets an episode. We spend about a month at the top of the year talking about season-wide mythology, and where we want the characters to go, whatever. Then, when we start actually breaking the episode, we usually know, or at least are aiming for, here’s where we have to build to this character moment, or this plot turn, or this step in the mythology.

We have that guide to start with. Then, we spend, it takes about, for us, three, three and a half weeks to break an episode. We probably spend two of those weeks just talking through character psychology. What’s the character thinking? Where do we want them to grow in this episode? What’s the thing they want most in the world? What’s the thing they’re afraid of most in the world? How do we make the thing they’re most afraid of, stand in the way of the thing that they want?

How does that relate to their childhood, whether it’s on camera or not? We’re just talking, talking, talking trying to dig as deep as we can into the psychology. Eventually, it coalesces around, I’d say per character, like three or four beats. They start here, they grow here, this throws something in their path, and then they end up there.

John: As this is within an episode, each character will have three or four beats. That’s assuming all characters are in all episodes. There may be, obviously, places where people are off, but you’re also going to need to find ways, like people are just not in their own scenes, they’re in scenes with other people. You want to make sure that the scenes they’re in with other people are progressing both of their storylines.

Eric: Right. One thing I learned as the show went on, because we have 14 main characters, right? Though we spend our time thinking emotionally about those characters, I learned very quickly that you need to double and triple people up into the same story, because there’s just not enough– You can’t have 14 separate stories in a one-hour show, and already we have too many storylines.

The biggest challenge of The Boys is there’s too many stories. It’s like Game of Thrones in a way, where sometimes you want to just sit with a story longer than you can, but you have all of these other stories to service to keep the machine going.

John: With this new season, at the end of last season, it’s pretty common now to burn down everything at the end of a season, so that you can come back to the new season and start things over. You did a very big burn down of everything at the end of this last season, and including our expectations about what is supposed to be happening. In that first episode of the new season, which I’ve not seen yet, as we’re recording this, how much are you thinking about getting the audience back up to speed? Are you expecting them to just start in the middle, and figure out what’s happening behind it? Those blue sky discussions must be a really important part of thinking about your season.

Eric: Mileage varies and taste varies. I prefer throwing people into the middle of it, and then slowly revealing the information that got them there. We like to play, we’ve done it a couple seasons now, where we almost play a game of, how do we reintroduce the character in the craziest place, or the most unexpected place we can put them, and then explain how they ended up there. In season 3, like Hughie is in a suit, and he’s Butcher’s boss.

John: That’s right.

Eric: You’re just like, “What? Wait. I don’t understand.” Then you realize, “Oh, he’s working with Victoria Newman, and he’s the head of this– He’s one of the co-heads of this agency.” You tease it out, so that by the end of the episode, they understand everything, but that you don’t front load the exposition. If anything, you back load it. I think that’s more fun. That’s what we try to do for the– That’s how season 5 opens.

Look, it was really helpful that I had pre-negotiated with Sony and Amazon that they were going to allow me to end the show on my terms, and that the fifth season was going to be the final season, because that allows you to blow the doors off it, like you said, in the season 4 climax, because you know you’re not holding on any chips anymore. You can go all in. That freedom allowed me to do the size of the finale that we were able to do that I don’t think I could have done otherwise.

John: Also, you don’t have to hold back any beats for characters that you were like, at some point, we would want to talk about this aspect of Hughie, we want to do this thing. At some point, Jim and Pam from The Office, you want to see them get married, but when are you going to do that? It is very liberating to know the end of a thing.

Eric: Beyond just the simple ones of, you can kill people off, which is fun, but you can also have them have conflict that is irreparable, because you don’t have to worry about bringing them back next season. You don’t have to say, “Well, that’s character assassination, you guys. We still have to live with that character.” You don’t have to do any of that. It’s very freeing.

It’s also super intimidating, because you can count on one hand the amount of truly great series finales. The landscape is just littered with corpses of shows that did not stick the landing. That’s a really intimidating– This is the first time I’ve been able to end a show. This is my first stab at it. I’m appropriately terrified of, are we sticking the landing? What do we need to do? Is it happening? Is it emotionally satisfying? Is it unexpected? I lose a lot of sleep over trying to land this plane.

John: I’m not asking for any spoilers, but looking back to your decision process about the season, did that mean you really came into the room thinking about, “Hey, what are the questions we want the series to answer? What are the payoffs that, we as creators, and as an audience are hoping to find in that, and then working towards that?” Is it just, you really are reverse engineering a bit?

Eric: Yes, that’s exactly right. Again, structure is so important to me, and I’m a little OCD, and I just hate the idea of moving forward into a horizon that I don’t know, or understand. I want to know where I’m going. In the beginning of the season, we talked about– The way I phrased it was like, “Okay, let’s say all the action is over, and now it’s like the 10 pages of wrap up, set to like the slow part of Laila. What do we want to see? Who’s alive, who’s dead, the ones who are alive, what are they doing? Where do we want everyone to end up? We figured that out. We figured out that final montage is one of the very early things. Then, it was like, “Okay, so how do we get there?”

John: What are your favorite series endings? What shows do you feel like actually really stuck the landing?

Eric: Breaking Bad is an annoyingly good ending.

John: Absolute monster that Vince Gilligan, yes.

Eric: He’s so annoying, like he’s delivered two different shows that have never had a bad episode, and both stuck the landing, and it’s annoying how good he is. Those are the two that really come to mind, Saul and Breaking Bad.

John: Your description of the resolution, and the song playing over it makes me think of Six Feet Under and which just–

Eric: Yes, that’s a great one. Yes, really good. One of the best actually.

John: Absolutely. Where it’s just thematically like, “Oh, we’re all going to die. This has been a show about death. We’re all going to die. Let’s look at how these characters die.”

Eric: Yes. No, for sure. Six Feet Under is a great one. Again, there’s not many. [chuckles] I can’t think of that many.

John: Yes, and it shows that we absolutely loved, where you look at the last episodes like, “Yeah, okay.”

Eric: Yeah, okay. You’re sending people out into the parking lot with a bad taste in their mouth.

John: Yes, exactly.

Eric: It colors all the good work you did before it.

John: Yes, people’s frustration with both the ending of Lost, and the ending of Game of Thrones. It is weird how it retroactively makes people like decide they didn’t like the series. It’s like, “No, I can show you evidence that you’ve loved this show.”

Eric: When you think of the unbelievable undertaking to make those shows, how hard those showrunners worked, and the pages and pages of just top tier quality, and because they didn’t stick the landing, everyone’s like, “Yes, I don’t know about Lost.” You’re like, “Oh my God, that show changed television.” Poor Damon Lindelof who has to write essays about defending the ending. You’re like, “Dude, you made one of the great shows.” Anyway, I’m really nervous.

John: Here’s hoping you won’t have to write essays defending the ending and The Boys.

Eric: Oh my God. Cut to my Hollywood Reporter op-ed piece of why The Boys made sense.

John: Yes. Let’s get to some listener questions. Drew, help us out. We have one here from Scott.

Drew Marquardt: Scott writes, while a bottle episode is always locked to a particular location, is there a term for an episode that exclusively follows a particular character? Recent examples include the Severance episode that only featured Cobel and Salt’s Neck, or The Bear that was just all a Tina backstory. I can’t think of a phrase I’ve ever heard used to describe this. Is there one you can think of, or suggest?

John: Eric, I was a little stumped for a term here too. It feels like a thing you actually just maybe describe, because we know what that is, but I haven’t heard a common industry term for that.

Eric: No, I haven’t either. Funny enough, I’ve heard it about two people, a two-hander.

John: Oh, yes.

Eric: Obviously, I’ve heard bottle episode. The closest term I can think of that we actively use is, it’s a change-up, because it’s more about what’s your structural change-up from what normal structure of the episode is. We’re doing not particularly that, but we’re doing a change-up this season, where we just blow out our old structure, and do a totally new one. Change-up, I guess. We did them a lot on Supernatural.

John: Yes, a change-up makes sense. Side quest is also a thing. Just that sense of like, you’re taking one character outside of the main story space, and letting them do a whole separate thing. There’s a series I’m pitching that, where one of the episodes definitely does do that, and actually tracks a bunch of things we’ve seen, but from a completely new perspective, and point of view. It’s almost a convention at this point, but I have not heard one common.

Eric: No.

John: Especially with that.

Eric: Whoever wrote that should pick the phrase.

John: Pick the phrase.

Eric: Make it happen. They can give birth to it.

John: All right, we got a question here from Ethan.

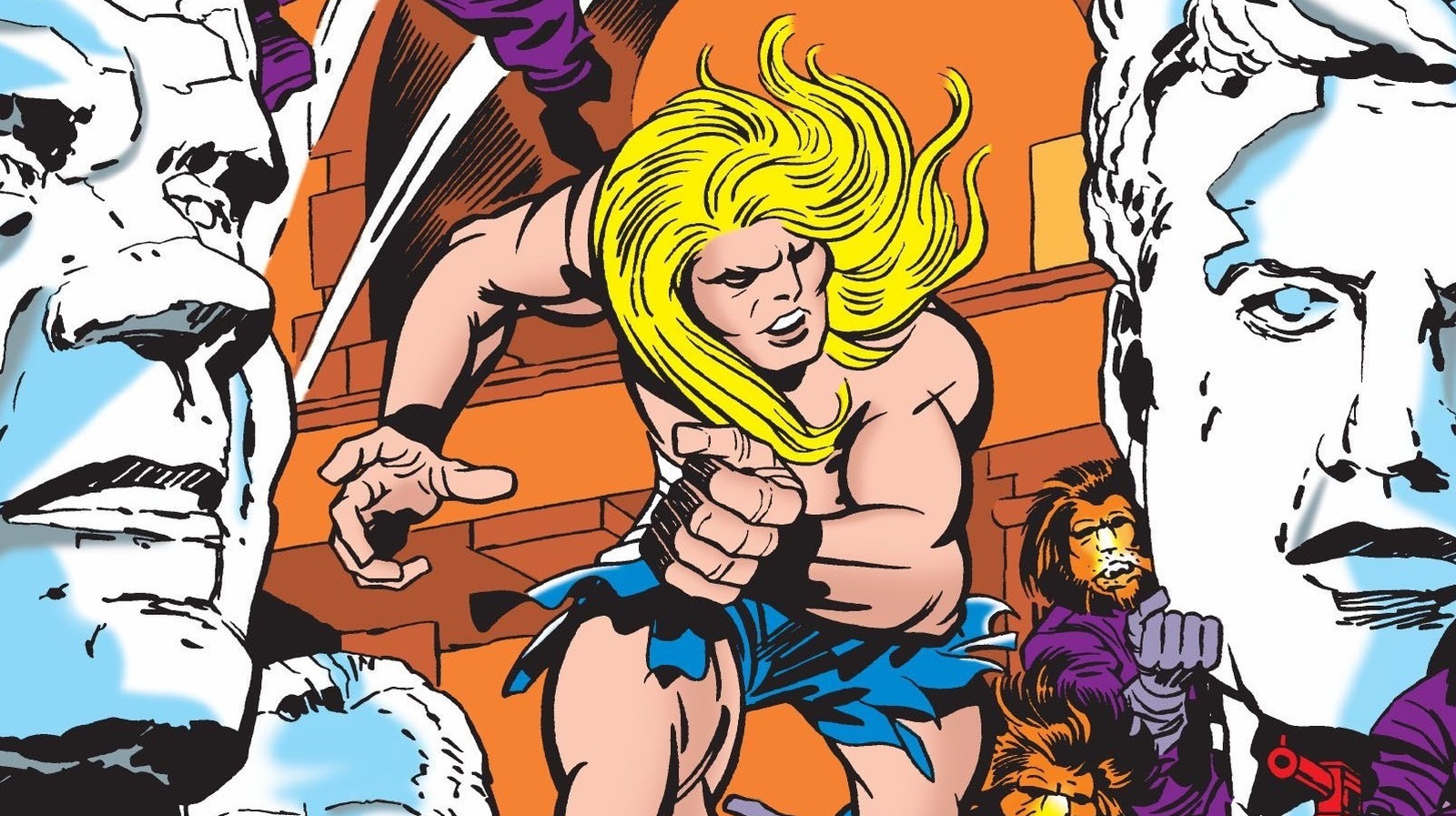

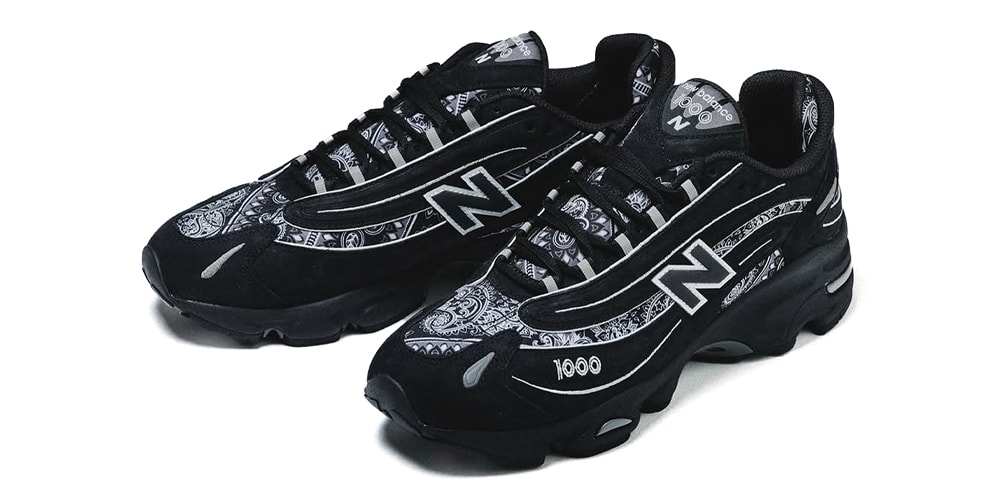

Drew: Ethan writes, I’m working on a live action script that pulls a lot from the visual language of comic books. I’m trying to do this in a nuanced way, not like Scott Pilgrim or Spider-Verse. I’ve cracked the formatting on some visual elements like multiple panels in one shot, but something’s stumping me. How would you write a quick change in color, or background to emphasize an impact? What about silhouette? I’m sure just saying that is the simplest way, but I’m looking to streamline it. I don’t like to break flow, but I want to sell the style.

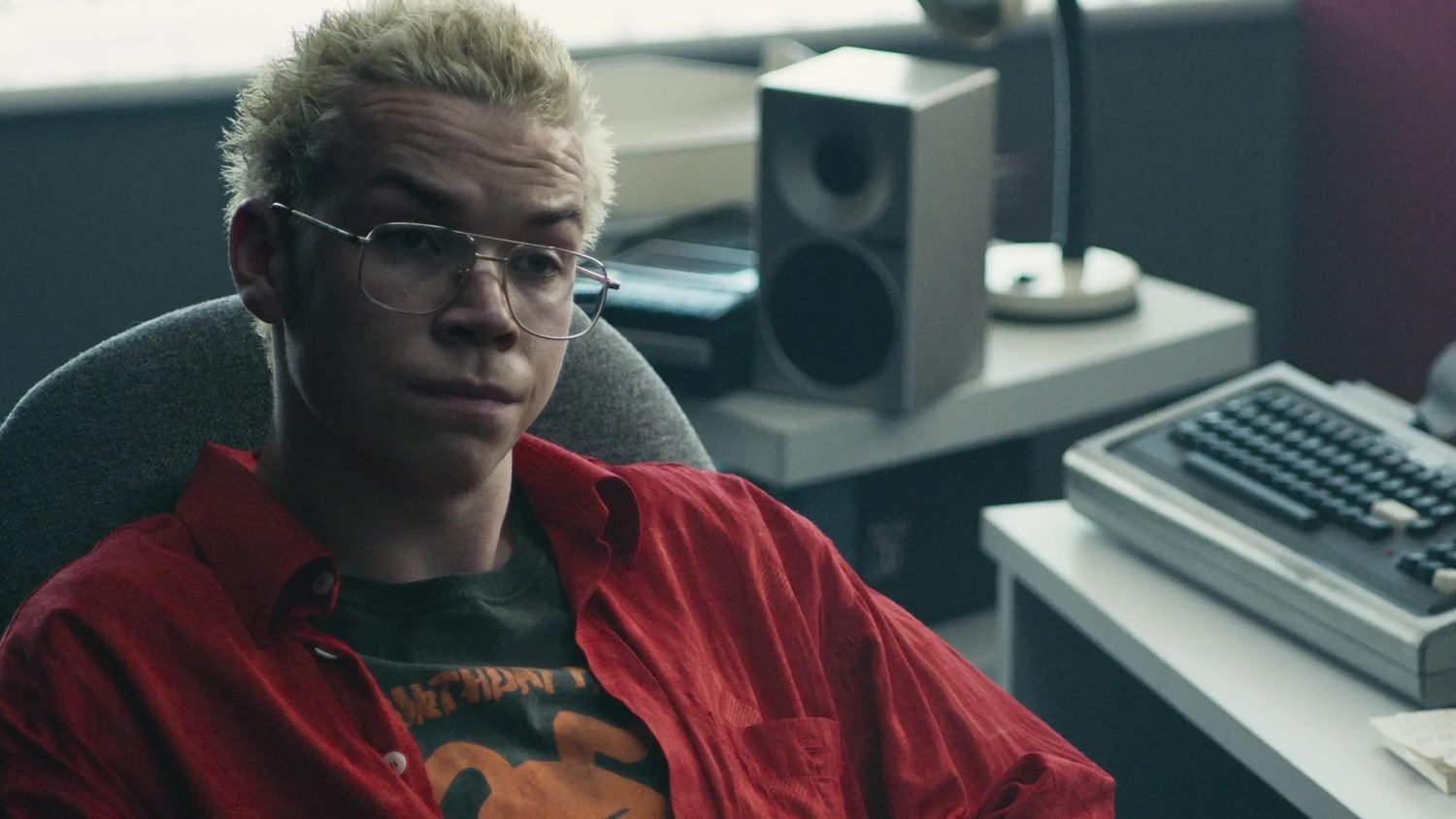

John: All right, so the images that we’re looking at here, I’m not sure what this is from, but the protagonist here is on a purple background, and then this woman shows up and slaps him, and it’s a yellow background. Then, the slaps are always on a different color background. It’s visually striking. Eric Kripke, you are a person who has adapted a graphic novel series, comic books, into another form. What do you think about this?

Eric: I’m going to say something like annoying and ice watery, which is, they’re different mediums. Comics, because I wrote a comic for Vertigo, and so I really got inside it. Comics, it’s a medium of space, and TV and film is a medium of time. They do not connect one-to-one. I actually think you’re risking something in your story to try to make it to keep the fidelity to the comic too high, because they just don’t have the same rhythms.

I would suggest, don’t focus on any of it. Leave it to the director, and just worry about making the characters nuanced, and complicated, and great, and a tight story that keeps turning.

John: Yes, thinking about The Boys, you’re clearly in a heightened universe. You’re looking at the pilot script for that. We can see that we’re in a heightened universe that feels comic-adjacent, but you’re not trying to emulate the specific styles of what it would look like on the page. There’s none of that stuff. Unlike, Scott Pilgrim, or Spider-Verse where you feel the intrusion of those elements onto the form, we’re not seeing that in your show. We know it’s in a comic space without having the conventions of comics.

Eric: Right. I think, look, I think Scott Pilgrim is one of the very few exceptions with a lot of fidelity to the original material, and it worked. I’d say much more often, they don’t. Damon’s Watchmen was so much more interesting than the movie, because he went his own direction with it. Yes, I would say, it’s about finding what’s unique about your story. The Boys, for instance, what defined a lot of the visual language that Dan Trachtenberg directed the pilot, and said a lot of that language is our gimmick, or our original little bauble was, what if superheroes existed in the real world?

You take this absurd concept, which is these magic flying people, but then how does that really work in the world we’re living in? In that tension, that’s where the show lives. Once we knew that, we knew how to make, someone-ism comes down to earth, and they seem like a God, but then they have to take a shit. It really finding the thing that is your, for lack of a better term, whatever your concept is, letting your visuals flow from that is good, because that’s a– We keep saying, “Well, what can we do that no other show can do?” That always brings us back to presenting something that stems from our concept.

John: Also, this brings us right, all the way back to the challenge you had going from the short film of Battle of the Sexes to a feature film. It’s like the world building didn’t make sense. The world fundamentally didn’t fit together right with those things you were trying to put together. In The Boys, it’s a heightened place, but within the rules of The Boys, things do actually make sense. There’s a consistency, there’s an internal consistency behind the different elements.

Eric: Right. Of course, yes, exactly. I take a lot of pride in maintaining that consistency. I drive my production designer nuts with– The posters in the background, I make him do 12 versions of, because I’m like, “Well, that doesn’t quite fit.” That character wouldn’t have been in that movie at that time. I got really obsessive with it, because it’s just fun. The point is, the rules don’t have to actually be logical, but they do have to be consistent. I think once people can do that, you can feel the internal logic of a piece.

John: A thing that I’ve always wondered about with The Boys, is that why Hughie, or some of the other person doesn’t point out like, “We must be living in a simulation.” There’s no way that these physics could possibly make sense. We have scientists, but then scientists could not possibly explain the things that are actually happening here. This must be a simulation. Is that an idea that ever came up in your thinking, and your development? That Hughie or some other character’s like, “No, this is impossible.”

Eric: No, never did. We always said, the show only has one slippery banana, which is compound V. You buy it, because the fact that it was born out of concentration camp testing. It’s like just this side of believable that you could make something like that, if you had thousands of people you could torture Mengele style. We always say, that’s the only magical thing. People just believe that this chemical can do this thing.

John: Because it’s a central premise. Without that central premise, the whole show doesn’t exist. People are willing to buy it, because you’re asking them to buy one thing versus a bunch of little small things.

Eric: Right, exactly. every time someone pitches me some James Bondian set piece, or some super high-tech, “Oh, he’s flying in on a flying green goblin thing.” I’m like, “Who invented that? Where did that magic come from?” We only get one magical thing, and it’s this vial of blue shit. That’s it.

John: Yes, so if aliens showed up in The Boys, it wouldn’t make sense.

Eric: Wouldn’t make any sense because we get one magic thing.

John: I loved the show, True Blood. One of the frustrations I have with the show is, I did feel like they kept adding layers onto it that didn’t all feel consistent with the premise that we’d had established in the early seasons.

Eric: Yes, but a beautiful metaphor, though, that show, yes.

John: Oh, so, so good. We’ll talk more about blood in the bonus segment. First, let’s go to our one cool thing. My one cool thing for people to check out this week is a video, so this was during the Olympics– Well, the Olympics that were in Paris, during those opening ceremonies along the Seine, which went on really too long for my taste, but there was a moment where there’s the Minions do this little segment, where the Minions are in the Seine, and they’re in a submarine.

I love the Minions, and I was hoping that I could find just that segment, and it was actually as good as I remember, and I’m happy to report, it is just as delightful as I remember. It’s two minutes of the Minions having hijinks in a submarine. I think it’s absolutely delightful. It’s on YouTube, on the official Olympics little channel there. I’m going to put a link in the show notes too. Two minutes of the Minions doing the Olympics. I recommend that.

Eric: One of my good friends and that we went to film school together co-directed the last Minions movie.

John: Oh, fantastic, who’s this?

Eric: Brad Ableson.

John: All right.

Eric: Yes, Minions.

John: The Minions are a fantastic creation, and they are so smartly done. They’re just these little creatures of pure instinct, and I just love them so much.

Eric: Yes. No, that’s a good one. That’s a good one.

John: Eric, what do you have to share with us?

Eric: Two things pop in my head. Can I say both of them?

John: Please. Absolutely.

Eric: One, and they might not be that obscure, so I don’t know, but the last movie I saw that really blew me away was Strange Darling.

John: I’ve recommended Strange Darling. I think it is so fantastic. I’m telling everyone to see it, and was so frustrated that more people are not seeing it, or that it’s not getting the award attention it should get.

Eric: It’s so good.

John: So good.

Eric: Brilliantly directed, but that script is so tight, and it’s such a perfect example of how to reveal information, and when to. I was blown away by it, and I would just recommend the less about that movie, the better.

John: Exactly.

Eric: If you’re listening to this, go on Amazon or whatever and watch Strange Darling.

John: There is blood, and so we’ll say that, if you cannot watch any blood, don’t watch the movie, but it’s just so smart.

Eric: It’s so, so smart. Then, the second one, is it okay if I say a podcast? Because it’s a podcast I’ve been listening to.

John: A hundred percent.

Eric: It’s fairly mainstream, but like The Lonely Island Seth Meyers podcast, where every week they talk about a short film that Lonely Island made during SNL. More than that, it’s a very nitty-gritty take of what it was like behind the scenes at SNL. If you’re a comedy nerd, which I am, they get so granular about how brutal it was, and the chaos that led to these sketches. Anyway, I find it both fascinating, and very funny.

John: Absolutely. It’s always great when you see like, oh, this thing that you love, they love it too, but their experience of it was so different, because they actually had to make it and it was exhausting, and they didn’t know if it was going to be good while they were doing it. They were surprised too.

Eric: I have a question for you actually, because I find that. My mom always used to say, “Cake never tastes as good when you bake it yourself.” I find that’s really true. Do you find, like so many other people like The Boys and Gen V more than me.

John: Oh, yes.

Eric: Because for me, it’s like a painful process, because all I’m thinking about is the mistakes, and what I wish I could have done better. Do you find that on your work?

John: I do some. People love the second Charlie’s Angels movie, and it was such a really painful experience for me, that I have a hard time experiencing the same joy they have for it. The flip side of that is, Big Fish was a largely good experience for me, and I’ve gotten to do the Big Fish musical again and again and again and again. It’s been just so much work in so many years of my life, but I can also get to watch it now, and actually just enjoy it as its own thing. I’ve crossed through that Rubicon of, it being painful too, appreciating that the pain is part of why I love it so much.

Eric: Yes. No, I get that. There’s certain episodes of Supernatural now that I can watch and enjoy, but I needed 10 to 15 years of separation to really enjoy it.

John: I don’t think either one of us is going to go back, and you will watch your Tarzan, or me watch my D.C. show. It’s like, there’s too much pain there. There’s not a lot of joy left in there.

Eric: Yes, I think that’s true.

John: Cool. That is Scriptnotes for this week. Scriptnotes is produced by Drew Marquardt, edited by Matthew Chilelli. Our outro this week is by Nick Moore. If you have an outro, you can send us a link to ask@johnaugust.com. That is also the place where you can send questions like the ones we answered today. You’ll find transcripts at johnaugust.com, along with the signup for our weekly newsletter called Interesting, which has lots of links to things about writing.

We have t-shirts and hoodies and drink wear. You can find those at Cotton Bureau. You’ll find the shownotes with links to the things we talked about today in the email you get each week as a premium subscriber. Thank you to our premium subscribers. You make it possible for us to do this each and every week. You can sign up to become one at scriptnotes.net, where you get all the backup episodes, and bonus segments, like the one we’re about to record on blood.

Eric Kripke, it’s an absolute pleasure talking with you. Congratulations on The Boys. I’m so excited to see how it ends.

Eric: Oh, thank you, this was so fun.

[Bonus Segment]

John: All right, Eric Kripke, from the pilot episode of The Boys, Hughie is standing there with his girlfriend, she gets run through by a speedster, and blood spatters everywhere. Hughie ends up wearing his girlfriend in blood, and that is the signal to us, like this is going to be an incredibly gory show. Did you know that from day one, from the moment of approaching this adaptation?

Eric: Yes, the gore is a really big part of the comic, and so we wanted to capture that. That was one of the things that I think made the comic unique from other superhero stuff. Again, if by putting superheroes in the real world with real fleshy people, the idea that they would just desecrate the human body over and over and over again, is a probably true fact that, just like the comic separated it from other superhero comics, it separated us from other superhero media.

John: Yes, so in Smallville, you’re not going to see blood, you’re definitely not going to see penises, you’re not going to see boobs.

Eric: Yes, and like what Seth Rogen always says, he’s one of our producers, is, “Shooting lasers from your eyes is not going to make someone shoot back into a door. They’re going to melt in the most horrific way possible.” We wanted to show that in a way that Smallville, or Superman never could.

John: Yes, let’s start with like the actual process of filming some of the goriness of the things, and how often your characters end up covered in blood, and how much they hate you for it? Talk to us about blood on set, and there’s probably a bunch of different ways you’re doing blood.

Eric: Yes, it depends on, there’s multiple departments that all have blood depending on where the blood goes. The three primary departments are makeup, wardrobe, and special effects. To hit them one at a time, wardrobe, they will pre-dress all of the blood all over the clothes. Makeup, if it’s on your face, and you’re playing with the character’s eyes, or whatever, you have to really carefully land all that stuff, so makeup carefully applies it.

In the hair, hair and makeup. Then, special effects is the coolest, most fun one because– For people who don’t necessarily know, there’s a difference between special effects and visual effects. Visual effects are the CG, and the computer, and all the stuff that happens afterwards. Special effects are the things that happen on the day, the explosions, the snow, the rain, the blood.

John: The squibs, yes.

Eric: Squibs, yes. What they’ll do is, use the example of when Hughie’s girlfriend Robin gets run through by A-Train. It’s so fun to do, because the special effects guys literally have like a blood cannon. It’s like a shotgun, and it’s loaded with blood. One thing we learned is, it can’t just be blood. It’s blood and all of these little gummy silicone bits. Someone is off camera pointing it directly in Jack Quaid’s face, and they’re going to pull a trigger, and all of this goo is going to launch at high velocity in his face, and he needs to not blink.

John: Yes.

Eric: God love that guy. He’s amazing at it. It’s like you’re literally– He’s there in front, cameras rolling, special effects guys take over the call. They’re like, “Everybody ready, three, two, one.” Then, someone shoots a shotgun at point blank range into Jack’s face with blood. That’s how we would do that. They also– If a character explodes, which we’ve done a lot of, a lot of times, it’s just CG, and it goes to visual effects, because it’s quicker on the day. Other times, they’ll create like a huge blood bag just loaded with blood, and bits, and organs. Then, they’ll put an explosive in the middle of it, and detonate it. Then, visual effects will replace the person who’s standing there with the explosion.

John: That’s how you get the blood on the environment, and on the other characters who are standing around, which makes sense.

Eric: Yes. The fun fact about blood is, it’s a corn syrup based, which means it’s sugary. Which means it’s insanely sticky and horrible. It attracts bees. My actors are always pissed at me, because it’s awful.

John: Obviously, we’ve been doing corn syrup since the beginning. There’s some reason why it works really well, but it does seem surprising to me that a show like you that uses so much of it, there’s been no innovation. There’s no alternative substance that–

Eric: We’ve never done– No, we stuck to what works. In season 2, we put the guys inside of a whale.

John: I remember that, yes.

Eric: The whale is doused with barrels of corn syrup. There were bees everywhere. They were living inside it. It takes the guys days to shower all of this goo off, but it just– It looks good. It flings in the right way. It feels like what it’s supposed to. Now, you raised an interesting question. It was like, “Does it feel real? Does it feel like the way the audience has been programmed over the last 50 years to think that that’s what blood looks like?” It’s probably that.

One thing they do, because all of it takes time. A lot of times, when you’re seeing the blood puddles on the floor, those are actually plastic decals they’ll lay down on the floor, and they can just peel right off, because you’re looking for anything you can do to save time on the day.

John: Backing up to make sure I’m understanding properly. Blood I see on a character’s face, hair, that’s one department. Anything that’s on their wardrobe, that’s pre-dressed there. You’re not taking a clean shirt and putting stuff on it. It’s a specially made shirt that has something on it. You might have to adjust that over the course of progression of a day, because it’s not going to look the same right when it first happens, and five scenes later.

Eric: Unless you want the moment of the blood hitting it for the first time, at which point someone wears a clean outfit, and someone from special effects has that blood cannon, and are waiting to just douse the character.

John: Has working around so much blood, changed your relationship about physical trauma, and your blood itself? Has there been an impact for you?

Eric: It’s funny, in Supernatural, even though it had much more stringent broadcast standards, it had a pretty solid amount of blood. This show is way over the top. I am so squeamish with the real thing. My wife likes to watch this, like these pimple popper shows-

John: Oh, yes.

Eric: -and these surgery shows. I cannot watch. I cover my eyes. I squeal. I leave. I literally leave the room. I cannot watch the real stuff. But the pretend stuff, I could watch all day. Peter Jackson, early Peter Jackson movies, I find that stuff so fun, because it’s basically like just a different version of Muppets. It’s just puppets. It’s puppets, and ingenuity, and magic. It’s so fun. The real stuff is horrible.

John: Yes. It is interesting how different, the context matters for these things. On your show, which is over the top and cartoony, we come to accept that. Then, if you’re watching a medical show, where they need to cut into somebody like, “Oh my God, that’s so horrifying.” It just feels so different. Where you’re priming the audience for one set of expectations.

Eric: Yes, it’s actually hard, because in our first season, and at least a good chunk of our second season, we still retained the ability to shock, where you could have something happen that would make the audience go, “Oh, shit.” It’s been very hard, because what you don’t want to do is try to keep topping it, and you become this big overinflated piece of bullshit. You want to be really driven about it. It’s hard on our show when you are so extreme to still surprise people.

John: Yes. Well, once you’ve had someone like a miniature person inside when someone’s urethra, it’s sort of– You can’t.

Eric: Yes, it’s hard.

John: You start to stop trying to top yourself there.

Eric: Yes, it’s true.

John: Eric, an absolute pleasure talking with you about blood.

Eric: Hey, thanks, John. That was fun.

Links:

- Eric Kripke on IMDb and Instagram

- The Boys

- Battle of the Sexes short film

- Minions on the Seine!

- Strange Darling

- The Lonely Island and Seth Meyers Podcast

- Get a Scriptnotes T-shirt!

- Check out the Inneresting Newsletter

- Gift a Scriptnotes Subscription or treat yourself to a premium subscription!

- Craig Mazin on Instagram

- John August on Bluesky, Threads, and Instagram

- Outro by Nick Moore (send us yours!)

- Scriptnotes is produced by Drew Marquardt and edited by Matthew Chilelli.

Email us at ask@johnaugust.com

You can download the episode here.The post Scriptnotes, Episode 684: Landing a Series with Eric Kripke, Transcript first appeared on John August.

![Behaviour Interactive to Publish Killer Clone Game ‘It Has My Face’, Coming This Year [Trailer]](https://bloody-disgusting.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/ithasmyface.jpg)

![The Top 10 “Phantom” Movies and Media (We Think) [Halloweenies Podcast]](https://bloody-disgusting.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/phantom-list-and-movies.jpeg)

![Ideal Women [THE FAMINE WITHIN]](http://www.jonathanrosenbaum.net/wp-content/uploads/2014/03/TheFamineWitin-ad.jpg)

![Bravery in Hiding [on LUMIÈRE D’ÉTÉ and LE CIEL EST À VOUS]](http://www.jonathanrosenbaum.net/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/lumieredete3-300x168.jpg)

![A Couple of Kooks [MY BEST FIEND]](https://jonathanrosenbaum.net/wp-content/uploads/2011/11/my-best-fiend-bluray.jpg)