The enduring horror of Kiss Me Deadly

As Robert Aldrich's 1955 noir turns 75, the film lives on in the work of Cronenberg, Lynch and many more. The post The enduring horror of Kiss Me Deadly appeared first on Little White Lies.

Heavy breathing, bare feet running on the asphalt, and a desperation so intense that it makes a woman put herself in front of a vehicle barrelling towards her at 50mph. Robert Aldrich’s 1955 noir Kiss Me Deadly begins where many other films would find their emotional and narrative climax: psychiatric hospital runaway Christina (Cloris Leachman) runs along a road recklessly attempting to flag down passing motorists while trying to evade unseen pursuers. Though she eventually finds refuge in the sports car of private eye Mike Hammer (Ralph Meeker) this does little to relieve the tension. As the credits roll over their nighttime drive, the camera looking over their shoulders from the backseat, Christina’s terrified sobs ominously mingle with the Nat King Cole tune blaring over the car radio. When the pair are later ambushed by a group of gangsters, the flimsy illusion of safety finally comes crashing down and the roughneck Hammer briefly awakes from unconsciousness only to witness Christina being brutally tortured to death.

Aldrich’s live-wire overture doesn’t just set the stage tonally but thematically, philosophically, and politically as well. Hammer, having survived the thugs’ attempt on his life, decides to investigate Christina’s death, sensing there must be “something big” connected to the crime. His hunch proves to be correct, of course, and he ends up embroiled in the hunt for a mysterious box which is supposedly connected to the Manhattan Project. The case’s connection to the infamous military research program isn’t a coincidence; the world of Kiss Me Deadly is one that exists in the shadow of nuclear weapons and the film’s rendering of the Atomic Age isn’t one of post-war optimism but rather one in which the Trinity test and the subsequent bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki formed a political, moral, and cultural destabilizing event.

In fact, the tendrils of Little Boy and Fat Man have twined around every sphere of American life and the puzzle-box storytelling screenwriter A.I. Bezzerides makes use of in this loose adaptation of Mickey Spillane’s 1952 crime novel of the same name (give or take a comma) serves not as a showcase for his skills as a crafter of dense mysteries, but rather as an extension of the opaque nature of life in the midst of what is sometimes referred to as the Golden Age of Capitalism. The film burrows so deep into its own gloomy, paranoid, hysterical logic that it comes out the other side bearing a deeper, more ecstatic truth: not only is there an underside to the carefully manicured facade of 1950s America but that underside also bubbles uncomfortably close to the surface. More than that, it constitutes an integral part of the societal structure it dwells beneath.

It’s a tension that would come to permeate the ensuing decades of genre (and genre-adjacent) filmmaking. Tobe Hooper let post-Manson, serial killer and Vietnam War-era America loose on a group of laid-back hippie kids in his 1974 horror milestone The Texas Chain Saw Massacre; that same year Roman Polanski crafted his own hellish vision of Los Angeles with Chinatown. Nearly a decade later, Videodrome saw David Cronenberg transpose nuclear paranoia to the burgeoning information age by nesting conspiracies within even grander, more elaborate conspiracies. Famously, David Lynch’s nastiest film, 1997’s Lost Highway, took direct visual cues from Aldrich’s infernal coda for its own beach house-set finale wherein Fred Madison’s (Bill Pullman) macho guilt becomes the reality-distorting void at the center of the film.

Kiss Me Deadly’s influence expanded beyond North America too. French New Wave filmmakers took to its potent images and gut-punch sensibility, its subversive artfulness that was garbed in pulp. François Truffaut was particularly taken with the feverish energy of Aldrich’s fifth film – he ranked it amongst the works of Howard Hawks, Alfred Hitchcock, Jean Cocteau, Robert Bresson, and Orson Welles. He further compared Aldrich’s ease behind the camera to Henry Miller “facing a blank page”, a surprisingly apt comparison especially when considering the forceful and unrestrained virility that undergirds both Kiss Me Deadly and Miller’s work in general.

Aldrich’s unstable frames – also an influence on Atsushi Yamatoya’s Inflatable Sex Doll of the Wastelands and Seijun Suzuki’s corky yakuza films from the 1960s – paint the world as a chaotic vortex where even the men behind the curtain are barely in control. The sudden intrusion of the Manhattan Project into the goings-on of Aldrich’s thriller plays like a gonzo plot thread out of a Thomas Pynchon novel, stripped of its impish sense of humor; the gumshoe who gets in way over his head, meanwhile, is a noir staple, perhaps even a prerequisite for the genre to operate the way it does. Here, however, Hammer’s sleuthing seems to brush up against the very edges of the real, against what can be grasped rationally. It’s an escalation of stakes that adds a mythological weight to what started out as a simple detective story – what Hammer ultimately comes face to face with isn’t simply a sprawling, well-connected network of organized crime or even the more abstract notion of moral decay but the apocalyptic inevitability of American hegemony itself.

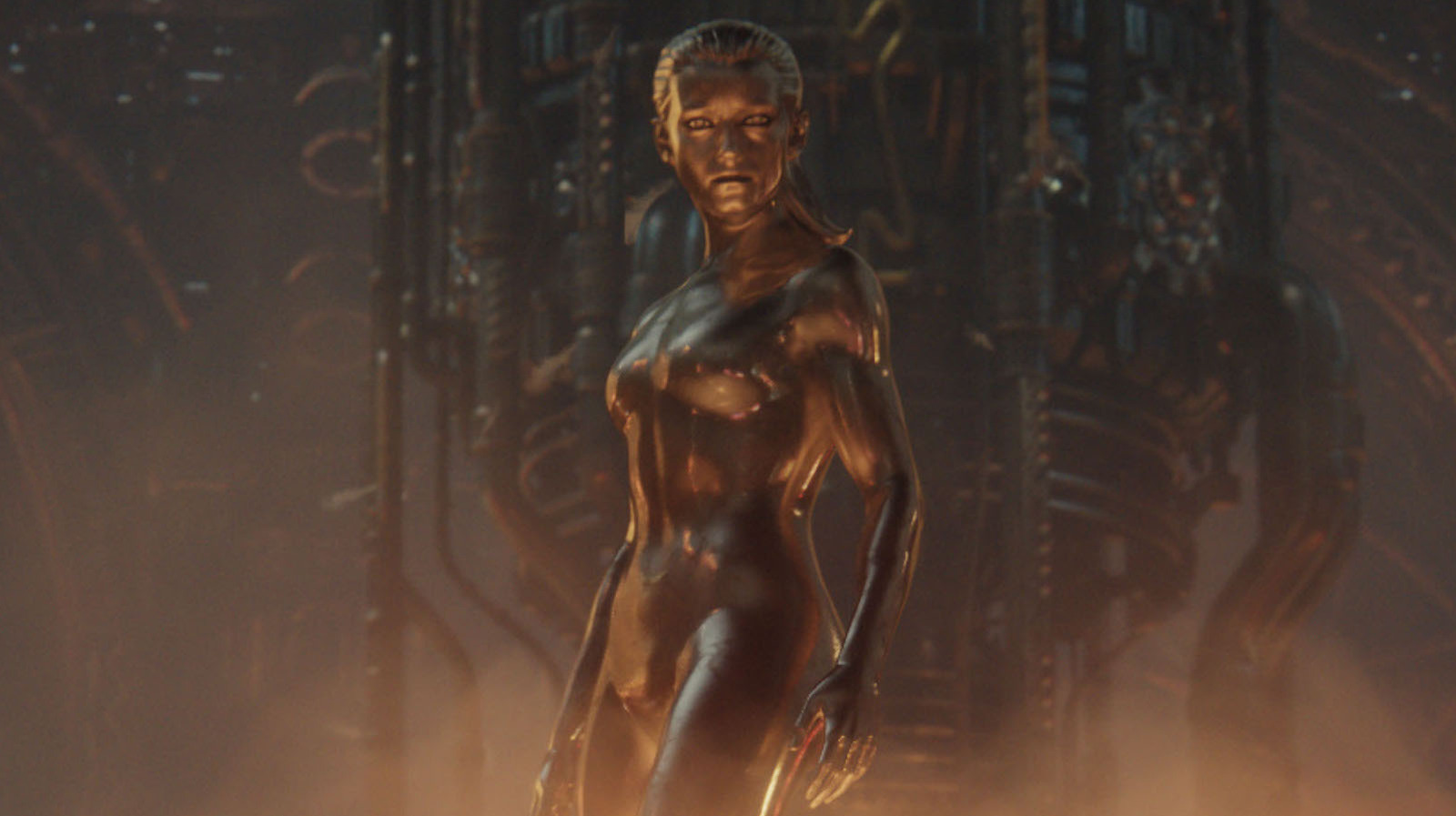

Curiously, Hammer’s instinct about there being more to Christine’s murder isn’t mere instinct but rather reveals a desire on his part to give meaning to the bizarre events he unwittingly became caught up in. But even as he hardasses, punches, and kisses his way through a gallery of crooks, patsies, and lusty women, meaning continues to elude him. The obsessive curiosity – a mirror image of Hammer’s desire-driven motivations – of one woman he meets, the unstable Lily (Gaby Rodgers), is what gives Kiss Me Deadly’s eerie finale: ignoring warnings not to do so, she opens the hot-to-the-touch box and is met by a blinding light and the sound of a demon’s death rattles before she bursts into flames that end up engulfing the entire beach house. The world the characters inhabit, the world after the war, after the bomb, is one where no deeper meaning can be gleaned from its grotesqueries – Pandora’s box has been opened but there is no hope left inside it.

The post The enduring horror of Kiss Me Deadly appeared first on Little White Lies.

![‘Play Misty for Me’ Explores the Thin Line Between Love and Obsession [The Lady Killers Podcast]](https://bloody-disgusting.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/Screenshot-2025-05-08-at-8.48.10-AM-1.png)

![Hollow Rendition [on SLEEPY HOLLOW]](https://jonathanrosenbaum.net/wp-content/uploads/2010/03/sleepy-hollow32.jpg)

![It All Adds Up [FOUR CORNERS]](https://jonathanrosenbaum.net/wp-content/uploads/2010/08/fourcorners.jpg)

![American Airlines Passenger Shocked By What Basic Economy Didn’t Include [Roundup]](https://viewfromthewing.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/american-airlines-do-not-occupy-seats.jpg?#)

-Nintendo-Switch-2-Hands-On-Preview-Mario-Kart-World-Impressions-&-More!-00-10-30.png?width=1920&height=1920&fit=bounds&quality=70&format=jpg&auto=webp#)

.jpg?width=1920&height=1920&fit=bounds&quality=70&format=jpg&auto=webp#)