Swamp Dogg: ‘We Did Damn Good. Success Just Came’

The music career of the man called Swamp Dogg has been like no other, with highs and lows, big hits and weird side trips, sometimes getting himself dropped from one label or another. He always bounced back. He’d begun in the 1950s playing traditional R&B, releasing his first record at 12 as Little Jerry Williams […]

The music career of the man called Swamp Dogg has been like no other, with highs and lows, big hits and weird side trips, sometimes getting himself dropped from one label or another. He always bounced back.

More from Spin:

- 5 Albums I Can’t Live Without: Paul Leary of Butthole Surfers

- Pearl Jam Welcome Peter Frampton For ‘Black’ In Nashville

- Lord Huron Get ‘Cosmic’ On Fifth Album

He’d begun in the 1950s playing traditional R&B, releasing his first record at 12 as Little Jerry Williams from Portsmouth, Virginia. What followed was an unlikely career as producer, songwriter, manager, A&R man, and hit-maker. And in 1970 he had an epiphany and became Swamp Dogg, a name befitting a mysterious musical superhero and chameleon.

“We did damn good. Success just came,” says Swamp Dogg, still a dapper dresser at 82, appearing onstage in colorful suits and carrying a cane. “I just kept doing things. If I believe in something, and if I can’t find investors to go with me, I’ll figure out a way to do it my damn self. And that’s what I’ve done off and on all of my musical life.”

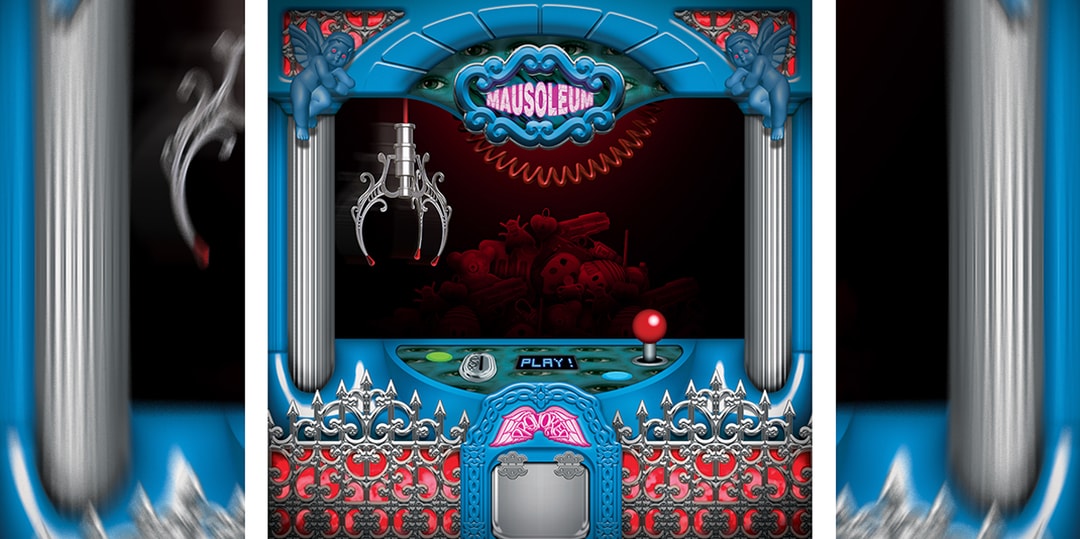

His career has had him working with multiple generations and genres, from Gene Pitney, Doris Duke, and Johnny Paycheck to Bon Iver, Jenny Lewis, and John Prine. And his series of solo albums of country soul and eccentric R&B are often presented with startling cover art. His 1971 classic Rat On! has him riding a giant rat. Another has him laying happily within a chili dog (his favorite dish, he says).

Now his story is being told in the hilarious and often moving Swamp Dogg Gets His Pool Painted, a feature documentary that debuted last year at the South By Southwest Film Festival.

Swamp Dogg was speaking from his Los Angeles home, the night before a trip to New York City, where he would be participating in Q&As at the IFC Center on May 9 and 10. The film is already playing in L.A., and rolls out to other cities over the next two months.

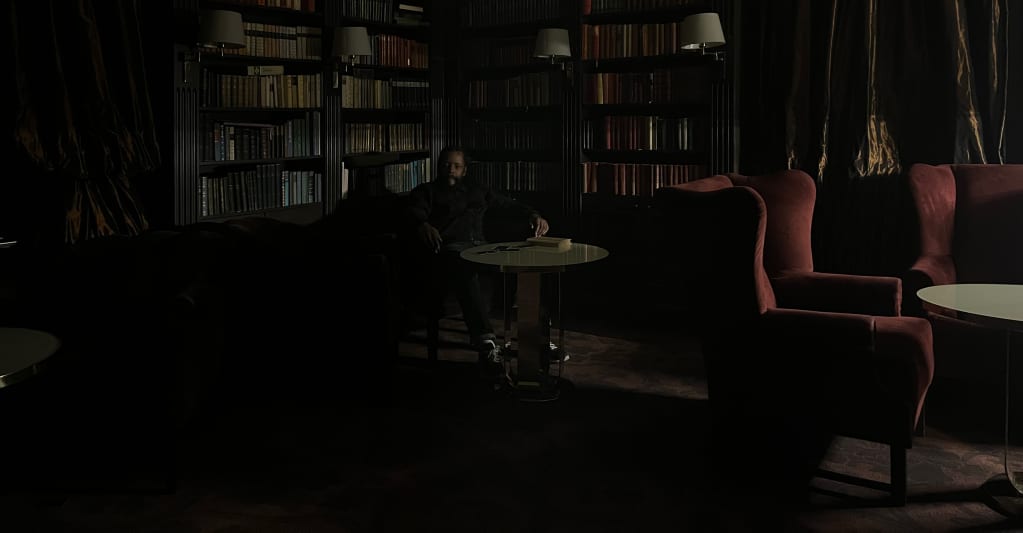

The film was directed by Isaac Gale and Ryan Olson, a pair of filmmakers based in Minneapolis, Minnesota, who originally landed at Swamp Dogg’s house in L.A.’s suburban San Fernando Valley to shoot a music video. What they found there was a community of players and a secret history waiting to be told.

Inside the house were gold and platinum records lining the entryway, with a grand piano crowded into one bedroom, and a pair of singular musicians in permanent residence at Swamp’s bachelor pad: Guitar Shorty and Larry “MoogStar” Clemons.

Shorty, an accomplished blues-rock player who was a direct influence on Jimi Hendrix, ended up as Swamp’s roommate and sideman when he decided to move to L.A. after his marriage ended.

“He called me and he said, ‘Man, you got a pretty big house. Can I rent a room from you a couple months till I can get on my feet and get everything going?’” recalls Swamp Dogg. “I said, ‘Yeah, Shorty, why not?’ So he came in and he was here for 18 years. I never charged him no rent, none of that. You know, you already in trouble. So why add to your troubles?”

His other roommate, MoogStar, is a cosmic and joyful multi-instrumentalist who had worked with Too Short and Humpty Hump, among many others. “He is a talented producer, keyboardist,” says Swamp. “The man can play at least 15 different instruments. Plus, he helped keep my shit fresh.”

Swamp Dogg first came into contact with singer-songwriter John Prine while working A&R for Atlantic Records at the beginning of the ’70s. Prine’s name was on a list of newer artists the label was ready to drop. But Swamp fell in love with Prine’s song “Sam Stone,” which tells the bleak story of a drug-addicted veteran and appears on his 1971 debut album. It’s now considered a country-folk classic, and Swamp recorded a cover the following year.

“I said, this motherfucker is going places,” recalls Swamp, who remained in touch with the acclaimed singer-songwriter for decades after. Prine appeared on two songs from Swamp Dogg’s 2020 album, Sorry You Couldn’t Make It. It was recorded in Nashville and was among Prine’s final recording sessions, captured by the documentary filmmakers.

They were talking about collaborating on more songs, but COVID hit, and Prine didn’t survive the pandemic. At the same time, Swamp has embraced opportunities to work with a younger generation of artists in his home studio and elsewhere, collaborating with Lewis, Bon Iver’s singer-songwriter Justin Vernon and Margot Price.

“When I get with new people, it’s like going to a six-week class” on the newest sounds and ideas, he notes. “That’s how I kind of stay in touch.”

In the 1980s, Swamp managed the electro/rap/R&B group World Class Wreckin’ Cru, which included a young pre-gangsta Dr. Dre, soon to be a member of N.W.A. “He was very quiet, intelligent, and he was a hard worker and he wanted to come up with new sounds and all that kind of stuff,” says Swamp. “That shows in the very first album that they put out. I knew he was destined for greatness. He’s the first billionaire rapper and producer.”

In the documentary, viewers get a glimpse of Swamp’s late wife and career confidante, Yvonne, in vintage footage, and her presence is still strongly felt in the house. With shooting starting in 2018, the film also captures some visitors to the Swamp Dogg home—Johnny Knoxville, Mike Judge, and Tom Kenny (SpongeBob)—sitting poolside with the veteran music maker.

“He’s got an infinite amount of stories of really cool people, and I think he’s pretty proud of that,” says Gale. “One of the pleasures is to just sit there with him and hear more crazy bonkers tales of everyone he’s met.”

One of those stories was Swamp Dogg’s appearance on the Jane Fonda-led Free the Army Tour, an act of protest against the Vietnam War in 1970. It was a radical move for any pop musician, and it cost him his deal with Elektra Records, but he has few regrets.

“No, I thought I was right,” Swamp says now. “It was fun. We got a lot of criticism, because Jane was heading it up and we called the thing FTA, which was Free the Army—which was really ‘Fuck the Army.’ And I was saying things about the president. I talked about him like a dog.”

Swamp Dogg carried on. And decades later, he saw his influence in action when Snoop Dogg emerged as a new hip-hop sensation. The older player couldn’t help but see the similarity in their chosen names.

“I didn’t like the idea of it at first, but then my wife had a good talk to me,” says Swamp. “I hadn’t patented the name Swamp Dogg. A lot of ‘doggs’ came out, [including] Nate Dogg. Oh man, they got a baseball team down in North Carolina calling themselves the Swamp Doggs. Yeah, that ‘Dogg’ thing came from me. I was the first ‘Dogg.’”

The film offers some meaningful recognition for a career that has spanned decades and multiple genres and time zones. At screenings attended by Swamp Dogg and his inner circle, they’re soaking it up.

“Him and MoogStar, they’re cracking up with their own jokes,” says Gale. “They’re loving it. Hopefully it leads to some people buying some Swamp Dogg records, because everyone should have them in their collection.”

Swamp Dogg has never stopped working, and isn’t about to now in his 80s, especially with a new documentary introducing him to a new wave of listeners.

“I don’t feel like an 82-year-old guy when I’m on stage,” he insists.” I start doing things and I say to myself, ‘Motherfucker, what are you doing?’—because I’ll be dancing and shit. I walk onstage with a cane and when I finish my set, I can’t even find the cane. There’s something that music does for me the way I guess cocaine does for other people. I never had any cocaine, so I can’t compare it, don’t want to compare. But music just gets all into me.”

To see our running list of the top 100 greatest rock stars of all time, click here.

![Hollow Rendition [on SLEEPY HOLLOW]](https://jonathanrosenbaum.net/wp-content/uploads/2010/03/sleepy-hollow32.jpg)

![It All Adds Up [FOUR CORNERS]](https://jonathanrosenbaum.net/wp-content/uploads/2010/08/fourcorners.jpg)

![David Zaslav Killed A TV Sequel To Tucker And Dale Vs. Evil; Here's What It Would Have Been About [Exclusive]](https://www.slashfilm.com/img/gallery/david-zaslav-killed-a-tv-sequel-to-tucker-and-dale-vs-evil-heres-what-it-would-have-been-about-exclusive/l-intro-1746813804.jpg?#)

![Natasha Rothwell Pitched Belinda’s Big Moment In ‘The White Lotus’ Season 3 [Interview]](https://cdn.theplaylist.net/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/09171530/NatashaRothwellWhiteLotusSeason2.jpg)

![American Airlines Passenger Shocked By What Basic Economy Didn’t Include [Roundup]](https://viewfromthewing.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/american-airlines-do-not-occupy-seats.jpg?#)

-Nintendo-Switch-2-Hands-On-Preview-Mario-Kart-World-Impressions-&-More!-00-10-30.png?width=1920&height=1920&fit=bounds&quality=70&format=jpg&auto=webp#)

.jpg?width=1920&height=1920&fit=bounds&quality=70&format=jpg&auto=webp#)