Dear Atlas: How Do I Safely Explore Abandoned Places?

Dear Atlas is Atlas Obscura’s travel advice column, answering the questions you won’t find in traditional guidebooks. Have a question for our experts? Submit it here. * * * Dear Atlas, I want to explore some abandoned buildings and ruins. What do I need to pack? What tips should I keep in mind? There’s something magical about visiting the world’s forgotten places, from deserted mining towns like the Okanogan Highland Ghost Towns in Molson, Washington, to abandoned Italian mansions like Villa de Vecchi in Cortenova. However, exploring these fragile places can be dangerous, even illegal. Travelers should do their research beforehand and pack the right safety equipment. But don’t worry, we’re here to help. Step 1: Make Sure You Can Visit a Site Always ensure you can legally visit any abandoned places. This can be as simple as asking the owner for permission (even the most derelict ruins belong to someone). You can use public records (which can be freely accessed through a local county assessor’s website) to find out who owns a parcel of land. If you have a friend who’s a real estate agent, they can also track down the owner. Once you find the owner, say you’re a photographer rather than an urban explorer—it’ll likely be easier to get approval that way. Some sites, such as the Roosevelt Island Smallpox Hospital Ruins in Southpoint Park in New York City or the Old Spanish Fort in New Orleans, are open to the public. Ruins in parks or on public land can typically be visited without getting permission, but do your research to make sure. Some tour companies also have special permission to visit abandoned places, such as Gunkanjima Island, a deserted mining town in Nagasaki, Japan, that several tour companies visit. Step 2: Get the Right Gear Wear sturdy hiking boots to prevent stepping on a rusty nail or twisting an ankle. Bring heavy-duty gloves (gardening gloves work) and dress in long sleeves and pants to protect yourself from rough surfaces and sharp objects. Carry a flashlight or headlamp to see in any enclosed spaces, even if you go during the day (which we’d recommend). Keep a respirator handy to avoid inhaling any mold or asbestos. In a pinch, you can use a medical facemask; however, only N95s or P100 respirators are effective against asbestos. Bring a first aid kit or have one in your car in case you cut or scrape yourself. You may also want to apply some insect repellent, and rub some Vicks VapoRub or a mentholated ointment below your nose to lessen the stench of any foul odors. Many ruins don’t have great cell service so consider downloading an offline map to your phone, having a physical map and compass, or carrying marking chalk so you don’t get lost at a large site. A doorstop can also be a helpful tool to make sure a door doesn’t shut behind you. Always make sure you have a clear exit path out of the building. You might also want to carry an air horn or pepper spray to scare off animals or other people. If you’re exploring internationally, consider getting travel insurance, which can cover unexpected medical care abroad. Note that these plans won’t protect you if you visit a site illegally. Step 3: Take Precautions During Your Visit Don’t explore alone. Tell people where and when you’re going and share your location using Find My Friends or Google Maps. If you can, visit with a friend. If you’re exploring low-lying, foundational ruins, such as the 14th-century church remains of Dvorine in Serbia, be aware of uneven ground and loose rocks. Test precarious steps with a boot or walking stick before stepping with your full weight. Foundational ruins, like those at Dvorine, pose fewer risks than sites with more than one story or an intact roof. If there’s a ceiling above you, it can fall. So it’s best to stay near structural supports when inside. Stay near walls or columns. Don’t walk through the middle of rooms where the floor and ceiling are weakest. If you see mold, avoid it. When you first get to a site, walk around the outside to get a feel for the layout, identify exits, and know where to avoid. If a ceiling has already collapsed in one section, stay away from that area. If the interior looks hazardous, keep outside the ruin and peer in through open windows or doorways. Visiting abandoned places can be thrilling, but that thrill isn’t worth an injury. Be safe, be smart, and have fun. Good luck! * * * Sarah Durn is a freelance editor and writer who previously served as an associate editor at Atlas Obscura. Her work has appeared in the New York Times, National Geographic, and Smithsonian. Her first book, The Beginner’s Guide to Alchemy, was published by Callisto and Rockridge Press in 2020.

Dear Atlas is Atlas Obscura’s travel advice column, answering the questions you won’t find in traditional guidebooks. Have a question for our experts? Submit it here.

* * *

Dear Atlas,

I want to explore some abandoned buildings and ruins. What do I need to pack? What tips should I keep in mind?

There’s something magical about visiting the world’s forgotten places, from deserted mining towns like the Okanogan Highland Ghost Towns in Molson, Washington, to abandoned Italian mansions like Villa de Vecchi in Cortenova. However, exploring these fragile places can be dangerous, even illegal. Travelers should do their research beforehand and pack the right safety equipment. But don’t worry, we’re here to help.

Step 1: Make Sure You Can Visit a Site

Always ensure you can legally visit any abandoned places. This can be as simple as asking the owner for permission (even the most derelict ruins belong to someone). You can use public records (which can be freely accessed through a local county assessor’s website) to find out who owns a parcel of land. If you have a friend who’s a real estate agent, they can also track down the owner.

Once you find the owner, say you’re a photographer rather than an urban explorer—it’ll likely be easier to get approval that way.

Some sites, such as the Roosevelt Island Smallpox Hospital Ruins in Southpoint Park in New York City or the Old Spanish Fort in New Orleans, are open to the public. Ruins in parks or on public land can typically be visited without getting permission, but do your research to make sure.

Some tour companies also have special permission to visit abandoned places, such as Gunkanjima Island, a deserted mining town in Nagasaki, Japan, that several tour companies visit.

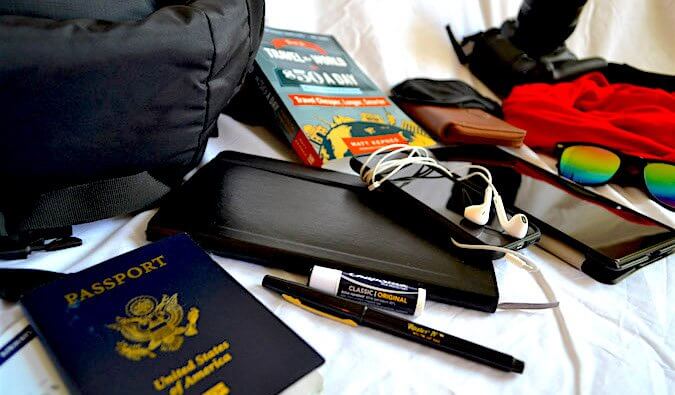

Step 2: Get the Right Gear

Wear sturdy hiking boots to prevent stepping on a rusty nail or twisting an ankle. Bring heavy-duty gloves (gardening gloves work) and dress in long sleeves and pants to protect yourself from rough surfaces and sharp objects.

Carry a flashlight or headlamp to see in any enclosed spaces, even if you go during the day (which we’d recommend). Keep a respirator handy to avoid inhaling any mold or asbestos.

In a pinch, you can use a medical facemask; however, only N95s or P100 respirators are effective against asbestos. Bring a first aid kit or have one in your car in case you cut or scrape yourself. You may also want to apply some insect repellent, and rub some Vicks VapoRub or a mentholated ointment below your nose to lessen the stench of any foul odors.

Many ruins don’t have great cell service so consider downloading an offline map to your phone, having a physical map and compass, or carrying marking chalk so you don’t get lost at a large site.

A doorstop can also be a helpful tool to make sure a door doesn’t shut behind you. Always make sure you have a clear exit path out of the building. You might also want to carry an air horn or pepper spray to scare off animals or other people.

If you’re exploring internationally, consider getting travel insurance, which can cover unexpected medical care abroad. Note that these plans won’t protect you if you visit a site illegally.

Step 3: Take Precautions During Your Visit

Don’t explore alone. Tell people where and when you’re going and share your location using Find My Friends or Google Maps. If you can, visit with a friend.

If you’re exploring low-lying, foundational ruins, such as the 14th-century church remains of Dvorine in Serbia, be aware of uneven ground and loose rocks. Test precarious steps with a boot or walking stick before stepping with your full weight.

Foundational ruins, like those at Dvorine, pose fewer risks than sites with more than one story or an intact roof. If there’s a ceiling above you, it can fall. So it’s best to stay near structural supports when inside. Stay near walls or columns. Don’t walk through the middle of rooms where the floor and ceiling are weakest. If you see mold, avoid it.

When you first get to a site, walk around the outside to get a feel for the layout, identify exits, and know where to avoid. If a ceiling has already collapsed in one section, stay away from that area. If the interior looks hazardous, keep outside the ruin and peer in through open windows or doorways.

Visiting abandoned places can be thrilling, but that thrill isn’t worth an injury. Be safe, be smart, and have fun. Good luck!

* * *

Sarah Durn is a freelance editor and writer who previously served as an associate editor at Atlas Obscura. Her work has appeared in the New York Times, National Geographic, and Smithsonian. Her first book, The Beginner’s Guide to Alchemy, was published by Callisto and Rockridge Press in 2020.

![Tommy Boy Director's Favorite Chris Farley Memory Involves A Classic Movie Star Impression And Some Car Chaos [Exclusive]](https://www.slashfilm.com/img/gallery/one-of-tommy-boys-most-quotable-moments-came-from-chris-farley-being-bored-exclusive/l-intro-1742930645.jpg?#)

![She Missed Her Alaska Airlines Crush—Then A Commenter Shared A Genius Trick To Find Him [Roundup]](https://viewfromthewing.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/alaska-airlines-in-san-diego.jpg?#)

.png?width=1920&height=1920&fit=bounds&quality=80&format=jpg&auto=webp#)

.png?width=1920&height=1920&fit=bounds&quality=80&format=jpg&auto=webp#)

![[Podcast] Should Brands Get Political? The Risks & Rewards of Taking a Stand with Jeroen Reuven Bours](https://justcreative.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/jeroen-reuven-youtube-1.png)