Zine Archives Preserve Trans Survival and Storytelling

On an August night in 1991, Nancy Jean Burkholder was kicked out of the Michigan Womyn’s Music Festival. It wasn’t because she was disrupting the event—it was because she was transgender. The lesbian feminist women's music festival, which had been an annual event in Oceana County since 1976, claimed that they had a “womyn-born-womyn” policy that excluded trans women from attending. Nancy left the festival grounds, devastated, and returned to her home in New England. When the festival rolled around the following year, Nancy did not attend, but her presence was still felt. Trans women could not go in, and neither could their supporters—but zines could. In response to Nancy’s expulsion from the festival, trans organizers and cisgender allies organized Camp Trans, a demonstration outside of the Oceana County festival. Though they were unable to enter, trans organizers and cisgender allies funneled literature into the festival. They posted flyers debunking gender myths on the port-o-potties and passed out surveys to gauge support for trans women among the festival crowd. The protest became an annual tradition, and zines were an integral part of Camp Trans. A 2001 Camp Trans zine, now held in the Queer Zine Archive Project, describes their goal to “start new dialogues about trans-inclusion and identity” and invite festival goers to their camp just across the street. These documents offer one of the few available histories of Camp Trans organizing. Along with other zines created by the queer and trans community, they are the subject of a growing number of private and public archives. Zines have existed for over 100 years—from the “little magazines” that Black writers created and distributed during the Harlem Renaissance to the fan-created, self-published comics of the 1930s where modern zines get their name. The second- and third-wave feminist movements, including the ones responsible for the Michigan Womyn’s Music Festival, used zines to organize protests and community action. Defined often by a limited run or circulation of 1,000 or fewer copies, zines are created by collaging together written word, printed images, and drawings to create a small book that is then photocopied and distributed. As a result, each one represents a time capsule of community existence and culture. From a 1991 Riot Grrrl zine held in the D.C. Punk Archive, to A queer and trans fat activist timeline created in 2010 and held in the London College of Communication Zine Collection, they capture the struggles and victories of community building. These handmade publications have found their way into the special collections and libraries of Duke University, New York University, Columbia University, Michigan State University, and more. Along with academic archives, there are countless independent collections like the Papercut Zine Library in Boston and Zine Archive Publishing Project in Seattle, which inspired Milo Miller and Christopher Wilde to create the Queer Zine Archive Project (QZAP) in 2003. Today it is one of the largest digital repositories of queer zines anywhere. Long before any of these official collections were built, private collectors were compiling archives in their homes. One of these people was Larry-bob Roberts, who created the zines Holy Titclamps and Queer Zine Explosion, a compendium of all the queer zines that people had sent their way. Larry-bob's archives served as a vital reference for Miller and other QZAP research fellows as they studied zine culture over the past 50 years. David Evans Frantz, a queer curator based in Los Angeles, says that private collections are often more common for queer and trans histories. “Before museums would even consider collecting or we could even imagine our lives highlighted in museums,” Frantz says, “much of that history saving is done through grassroots archives and libraries, the people that are collecting voraciously in their apartments.” They were the people who chose to collect the objects and documents that make up the histories that were not deemed acceptable or not noteworthy enough for museum spaces. For years, archives and museums resisted collecting zines for this very reason. “With zines, everyone can make a copy,” says Vee Lawson, a writing professor at San Jose State University, “so you might have multiple variants of a zine that have been photocopied over time, held in different collections.” Today, as a result of nostalgia for the fluorishing zine culture of the 1990s and growing disenchantment with social media as platforms like Facebook and Instagram, queer and trans people are returning to the tried and tested tools of small circulation, often self-published works of art. Lawson has written extensively about zines and uses them as teaching tools and assignments for their students. They first learned about zines in the 2010s, and came to the medium through online spaces like Tumblr, rather than in print. It wasn’t until Tumblr banned female-presenting

On an August night in 1991, Nancy Jean Burkholder was kicked out of the Michigan Womyn’s Music Festival. It wasn’t because she was disrupting the event—it was because she was transgender. The lesbian feminist women's music festival, which had been an annual event in Oceana County since 1976, claimed that they had a “womyn-born-womyn” policy that excluded trans women from attending. Nancy left the festival grounds, devastated, and returned to her home in New England. When the festival rolled around the following year, Nancy did not attend, but her presence was still felt. Trans women could not go in, and neither could their supporters—but zines could.

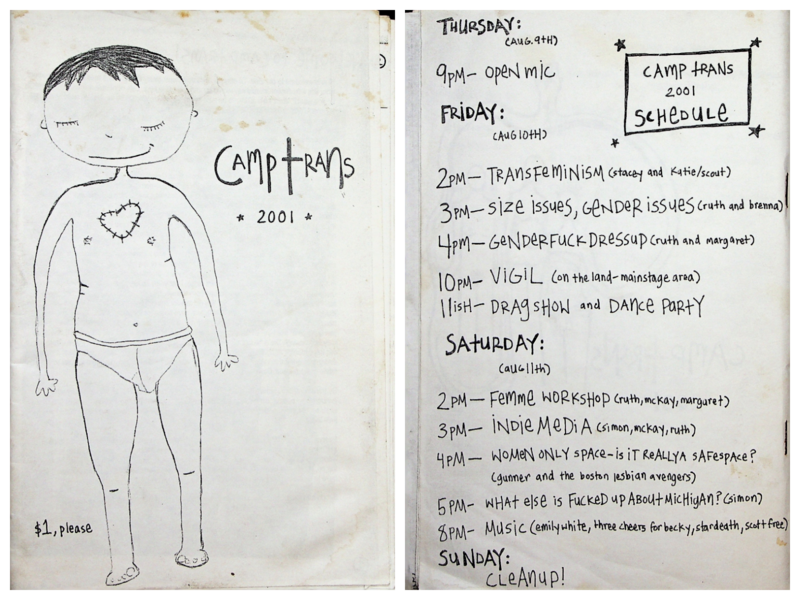

In response to Nancy’s expulsion from the festival, trans organizers and cisgender allies organized Camp Trans, a demonstration outside of the Oceana County festival. Though they were unable to enter, trans organizers and cisgender allies funneled literature into the festival. They posted flyers debunking gender myths on the port-o-potties and passed out surveys to gauge support for trans women among the festival crowd.

The protest became an annual tradition, and zines were an integral part of Camp Trans. A 2001 Camp Trans zine, now held in the Queer Zine Archive Project, describes their goal to “start new dialogues about trans-inclusion and identity” and invite festival goers to their camp just across the street. These documents offer one of the few available histories of Camp Trans organizing. Along with other zines created by the queer and trans community, they are the subject of a growing number of private and public archives.

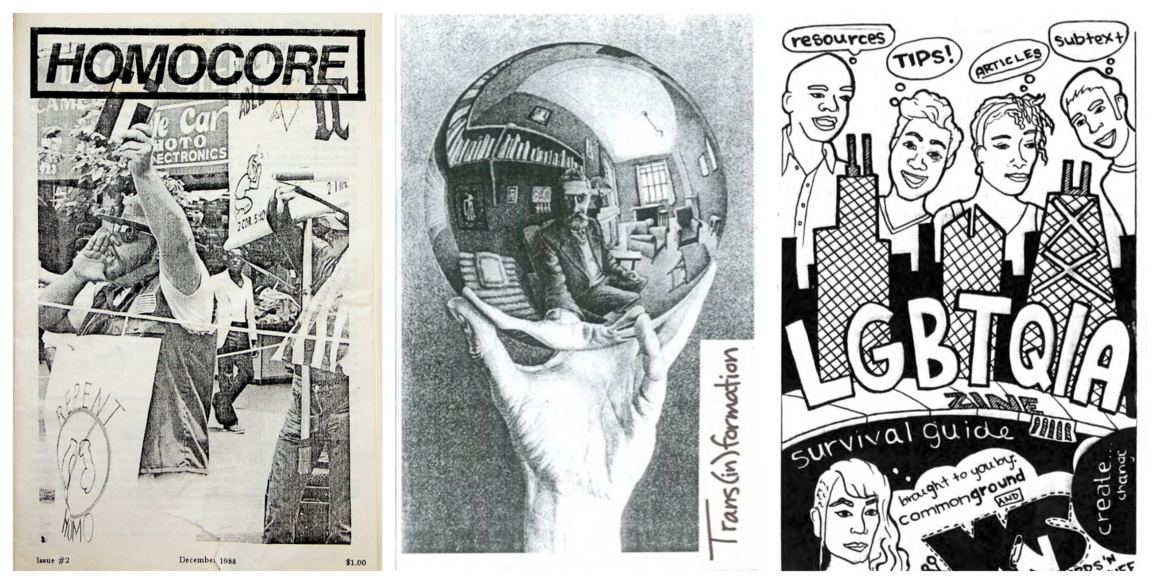

Zines have existed for over 100 years—from the “little magazines” that Black writers created and distributed during the Harlem Renaissance to the fan-created, self-published comics of the 1930s where modern zines get their name. The second- and third-wave feminist movements, including the ones responsible for the Michigan Womyn’s Music Festival, used zines to organize protests and community action.

Defined often by a limited run or circulation of 1,000 or fewer copies, zines are created by collaging together written word, printed images, and drawings to create a small book that is then photocopied and distributed. As a result, each one represents a time capsule of community existence and culture. From a 1991 Riot Grrrl zine held in the D.C. Punk Archive, to A queer and trans fat activist timeline created in 2010 and held in the London College of Communication Zine Collection, they capture the struggles and victories of community building.

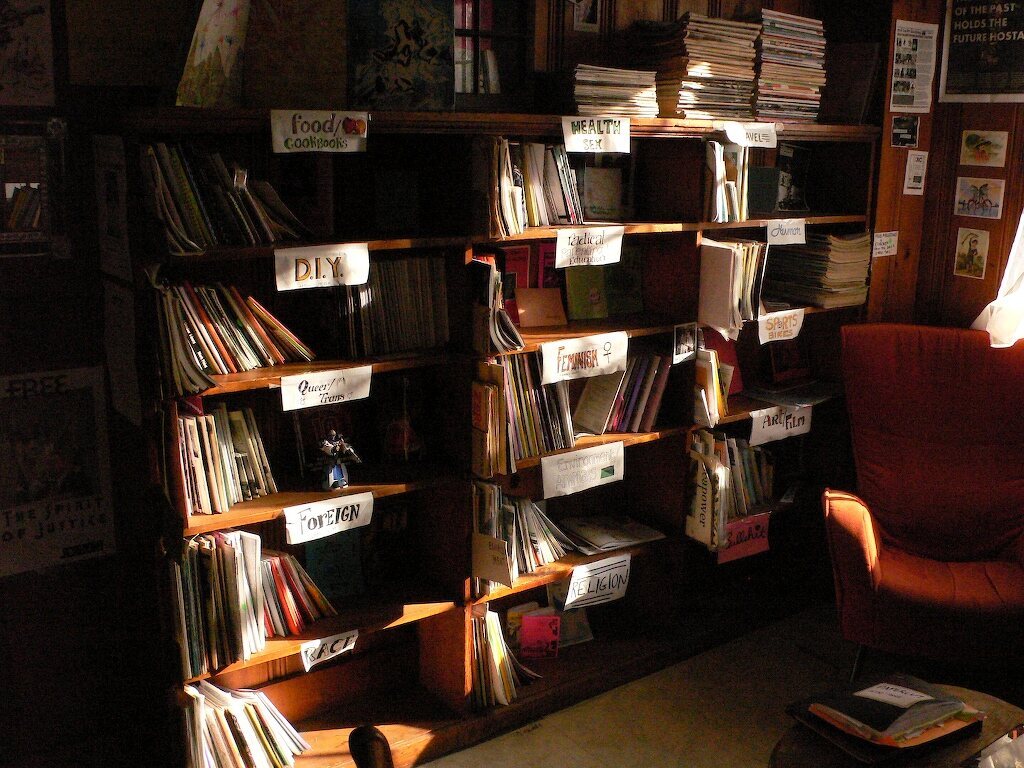

These handmade publications have found their way into the special collections and libraries of Duke University, New York University, Columbia University, Michigan State University, and more. Along with academic archives, there are countless independent collections like the Papercut Zine Library in Boston and Zine Archive Publishing Project in Seattle, which inspired Milo Miller and Christopher Wilde to create the Queer Zine Archive Project (QZAP) in 2003. Today it is one of the largest digital repositories of queer zines anywhere.

Long before any of these official collections were built, private collectors were compiling archives in their homes. One of these people was Larry-bob Roberts, who created the zines Holy Titclamps and Queer Zine Explosion, a compendium of all the queer zines that people had sent their way. Larry-bob's archives served as a vital reference for Miller and other QZAP research fellows as they studied zine culture over the past 50 years.

David Evans Frantz, a queer curator based in Los Angeles, says that private collections are often more common for queer and trans histories. “Before museums would even consider collecting or we could even imagine our lives highlighted in museums,” Frantz says, “much of that history saving is done through grassroots archives and libraries, the people that are collecting voraciously in their apartments.” They were the people who chose to collect the objects and documents that make up the histories that were not deemed acceptable or not noteworthy enough for museum spaces.

For years, archives and museums resisted collecting zines for this very reason. “With zines, everyone can make a copy,” says Vee Lawson, a writing professor at San Jose State University, “so you might have multiple variants of a zine that have been photocopied over time, held in different collections.”

Today, as a result of nostalgia for the fluorishing zine culture of the 1990s and growing disenchantment with social media as platforms like Facebook and Instagram, queer and trans people are returning to the tried and tested tools of small circulation, often self-published works of art.

Lawson has written extensively about zines and uses them as teaching tools and assignments for their students. They first learned about zines in the 2010s, and came to the medium through online spaces like Tumblr, rather than in print. It wasn’t until Tumblr banned female-presenting nipples in 2018 that they thought more deeply about it.

“What happened,” Lawson explains, “was that many of those queer and trans content creators who had formed the bulk of my online community were no longer allowed on the platform because they posted either truly explicit content or content that was queer or trans enough to be marked explicit.” As this online community imploded, they began to look for more stable, and anonymous, forms of queer communication. They found physical zines.

Lawson began creating their own zines in graduate school, using them to process the stressful and often classist world of higher education as someone from a working class background. They wanted to bring the theory they encountered in classrooms to their communities. Now they use zines in the classroom as an exercise for college students to think critically about their own experiences, tap into the medium as a space of exploration and discovery, and affirm the importance of the every day of trans and queer lives.

“[Zines] give a broad range of personal experiences of the everyday, so folks who don’t make the news,” Lawson said. “Folks who may even be stealth in their daily lives, who are just everyday people. So you get their stories, but you also get snippets of the materials they used to make these zines.” Some of their favorites include social media posts that people have printed out and glued into the booklets—pieces that may not exist in the future as platforms are phased out.

Some zines offer a glimpse into how communities respond to seismic political and social issues. Joey Gray started making HARDY in response to the socio-political climate in 2016, when Donald Trump was first elected to the presidency, queer communities were grieving the Pulse Nightclub shooting, and America was reckoning with the growing Black Lives Matter movement.

These zines also serve as vital spaces for sharing community knowledge, especially in a time when gender-affirming care is under fire. “It’s so important to have access to information about your community and your history,” says Lawson. Zines serve as knowledge-sharing tools about accessing hormone therapy and gendered spaces, and covert ones at that—to protect people who want to share information without being outed or that may be illegal.

The physical material on which zines are printed is not as important as the content itself. While they can be photocopied, many of these zines are ephemeral because they have not and will never end up in an archive and will never see a larger readership. But to QZAP founder and zinester Miller, this is at the heart of their work—zines are important historical documents that circumvent capitalist information sharing.

“We recognize that there’s so much that, especially in western queer world, does not get talked about in queer media,” Miller says. There are only so many column inches, only so many voices that can be represented because at the end of the day, these publications need to sell advertising to support their work. “Zines don’t do that,” Miller explains, “and one of the things that is so important about our collection is that we’re the rest of the story. We’re all the voices that don’t show up in other media and presses.”

With over 600 digitized zines available online and an estimated 4,000 physical zines from more than 10 different countries in their collection, QZAP proudly shares that “the only barriers are whatever you create for yourself. We don’t have publishers. We don’t have editors.” Their agenda, Miller asserts, is to make the world a better, safer place by creating a space where people can see themselves represented.

By design, QZAP does not know who is visiting or using the digital archive. They recognize that many of the zines in their collection can be considered “dangerous” because of who they represent and the ideas that they share, so they try to preserve the anonymity of people who access them. But the project isn’t entirely anonymous—QZAP offers internships and residencies, in-person efforts to research and record queer history.

This kind of community-focused work is critical because zines that do end up in university archives can feel inaccessible to the very communities whose histories they represent. “Zines do have a somewhat antagonistic relationship to academic institutions,” Lawson explains, because “when you take a zine and put it in a university library, it is preserved and technically it is usually open to the public but the folks who may be interested in reading that zine may not know that it’s there or that they even have access to the university’s special collections.”

Other community organizations like the Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual & Transgender Community Center also have extensive collections, and resources like the Digital Transgender Archive serve as online nexuses to compile all these materials in one place and make these collections searchable.

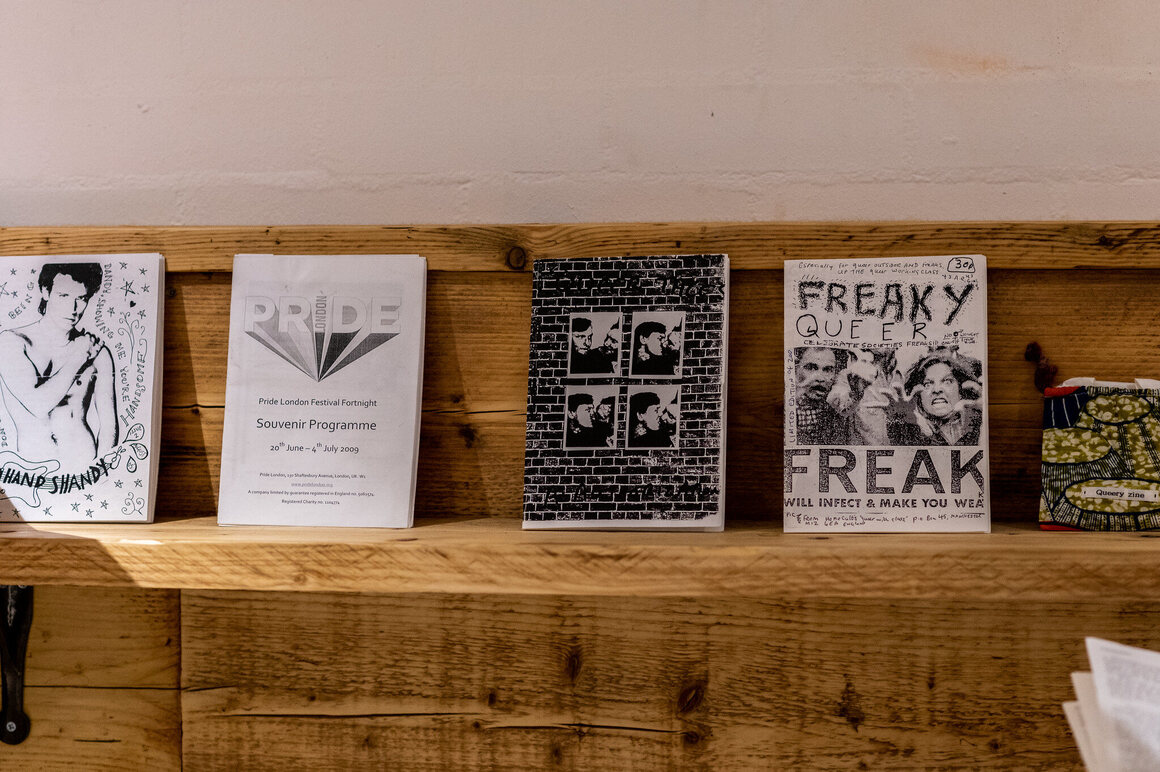

Independent zine archives have blossomed in the last 20 years to begin collecting underground queer community work, The Queer Reads Library in Hong Kong was founded in 2018, partially in response to the removal of 10 LGBTQ+ children’s books from the Hong Kong Public Libary. The traveling collection featured zines, and also inspired the Queer Zine Library collection, which was established in June 2019. Like the Queer Reads Library, the Queer Zine Library has no permanently accessible location but makes zines available through workshops, displays, and touring events.

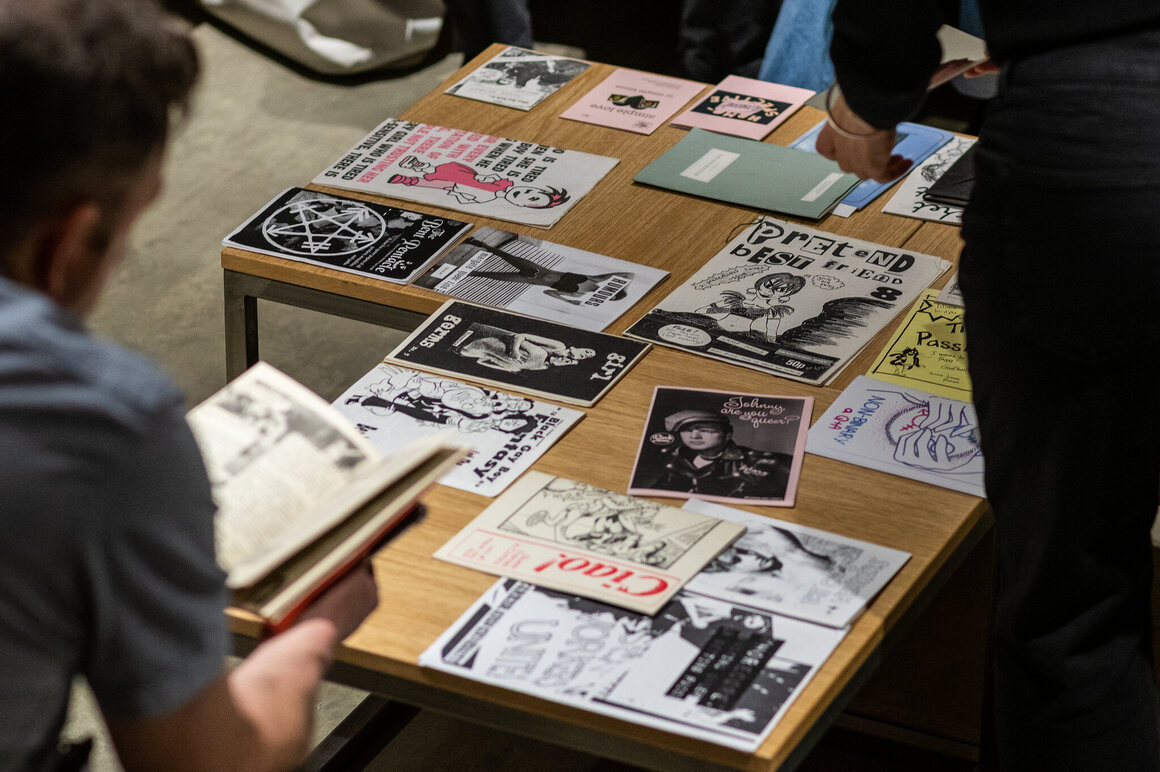

Zine festivals, indie comic events, and other community gatherings also serve as spaces to collect, trade, and distribute zines, although the pandemic temporarily slowed this work. Before founding QZAP, Miller organized the Media Alliance Zine Expo. One of the reasons they founded QZAP was because they and their partner wanted to capture and share the ephemera from Queeruption, an queer punk anarchist festival they helped organize in 2001. It was this question that led them to think about sharing their collection with a wider audience.

Today, many of the festivals are more local affairs that focus on how to serve their communities and recognize their histories. Aiden Bettine, the curator of the Tretter Collection in GLBT Studies at the University of Minnesota, operator of the Late Night Copies, and founder of the Midwest Queer and Zine Festival, explains that “we want to uplift regional zinesters who are making stuff that people in the region want to know and see.”

You can find zine collections in academic libraries, including Barnard College, Yale University, and Furman University, as well as public libraries in Seattle, San Francisco, Brooklyn, Chicago, and beyond. Sometimes they’re part of special collections, tucked away in special acid-free folders, while other times, zines are in integrated collections, stuck in between thick volumes and DVDs.

While these collections take different forms, they all provide access to a wide variety of materials. They preserve stories that are often left out of the historical record, like that of Camp Trans. It’s especially important now, when the word “transgender” is being removed from the written history of places like the Stonewall Monument and Dupont Circle. “We’re seeing our history erased in real time,” says Lawson. But as zine culture begins to flourish once more, new history is being written all the time. The most recent addition to the QZAP collection, Miller reports, was made the day we spoke with them.

![‘F1,’ ‘Weapons’ & Leonardo DiCaprio Give Warner Bros Some Life [CinemaCon]](https://cdn.theplaylist.net/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/01234706/HallTaylorDiCaprioCinemaConStage.jpg)

![The Depressing Relevance of ‘The Stepford Wives’ [Horror Queers Podcast]](https://bloody-disgusting.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/Stepford-Wives.jpg)

![‘Superman’ Sneak Features Feisty Krypto And Super Robots [CinemaCon]](https://cdn.theplaylist.net/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/01222722/SupermanFlyingArtic.jpg)

![David Fincher To Direct Brad Pitt In ‘Once Upon A Time In Hollywood’ Sequel Written By Quentin Tarantino [Exclusive]](https://cdn.theplaylist.net/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/31164409/David-Fincher-To-Direct-Brad-Pitt-In-%E2%80%98Once-Upon-A-Time-In-Hollywood-Sequel-Written-By-Quentin-Tarantino-Exclusive.jpg)