Valnet Blues: How Online Porn Pioneer Hassan Youssef Built a Digital Media ‘Sweatshop’

The owner of consumer facing entertainment websites Screen Rant, Collider, CBR and MovieWeb faces a lawsuit over exploitative work conditions The post Valnet Blues: How Online Porn Pioneer Hassan Youssef Built a Digital Media ‘Sweatshop’ appeared first on TheWrap.

Hassan Youssef is the classic rags-to-riches story. Born in Quebec, Canada, to immigrant Lebanese parents, he climbed his way to vast wealth by building a digital empire — first in porn, and now in entertainment news.

The founder and CEO of Valnet, based in Montreal, owns Screen Rant, Collider, MovieWeb and the comic book news site CBR, which according to the company, collectively drives 260 million page views every month.

In the past decade, Valent has scooped up most of the independently owned fan-facing news sites and is constantly seeking to acquire more, regularly sending pitch emails to independent content owners to buy them out and add traffic to its online juggernaut.

“Valnet has one clear goal: become the greatest content and digital investment company the world has ever seen,” boasted a press release announcing the acquisition of tech site How-To Geek in 2023. The company does not disclose revenues.

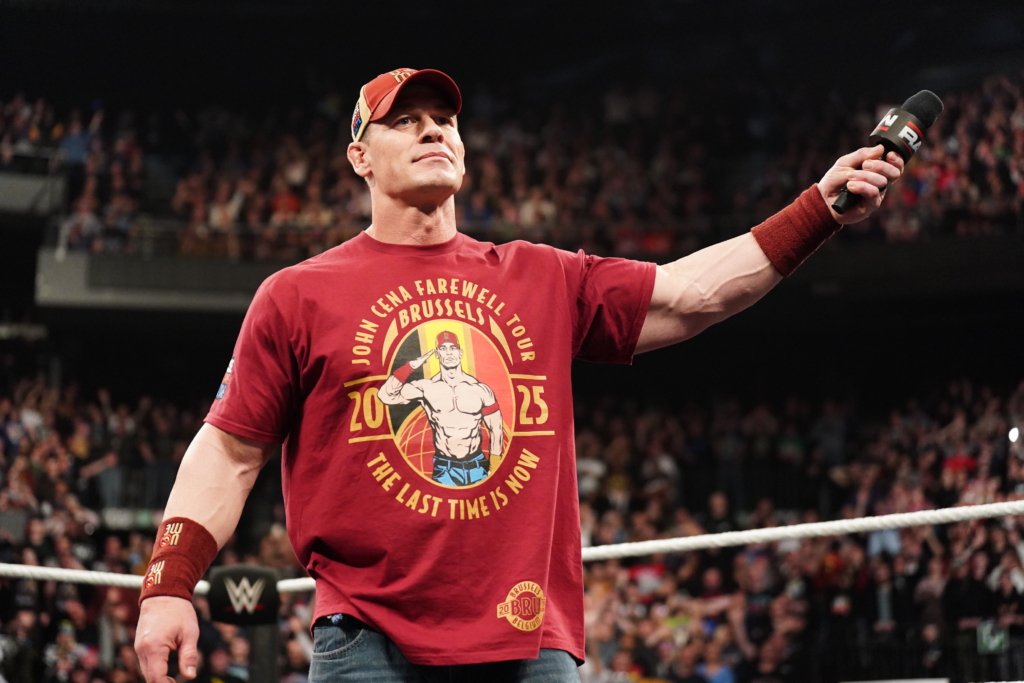

Lately, Valnet has been seeking credibility in Hollywood, such as with a March 11 screening Q&A and red carpet event at The Grove in Los Angeles, featuring Oscar-winning composer Hans Zimmer in honor of “the launch of music divisions on Collider and ScreenRant,” as a press release noted. Collider founder and editor-in-chief Steven Weintraub was the moderator.

But there’s a wrinkle in this story of a bootstrapping entrepreneur. When Valnet takes over a fan site, the playbook is well established: employees are replaced by contractors, compensation plummets and writers who complain land on a blacklist that blocks them from working for Valnet sites altogether.

TheWrap spoke to 15 current and former contributors who said Valnet routinely exploits and discards writers while prioritizing mass quantity over quality to churn out mind-numbing SEO bait.

“Everyone is underpaid, overworked and really pretty — extremely — exploited,” a former Collider contributor told TheWrap.

“They are a company without clear objectives or morals who present themselves as a safe haven for young and experienced writers, but they end up paying bargain-basement rates and forcing contractors to create junky clickbait,” a former Valnet contributor told TheWrap on condition of anonymity out of fear of retaliation.

Now one of those freelancers has filed a lawsuit claiming oppressive work conditions, and is seeking to establish a class action against Valnet. Daniel Quintiliano’s suit seeks $40,000 for violations including failing to pay minimum wage, overtime, provide meal or rest breaks and reimburse business expenses. The sum is unimpressive, but the prospect of extending this across a class of contractors has Valnet spooked — the company is now seeking signed releases from its contractors to not engage in any class action lawsuits against the company in exchange for $100 payment.

Few have accepted the offer, and a new offer has gone out … for just $200.

The Valnet Blacklist

Valnet may find it has few allies in the writing pool, because another operating tactic of the company is blacklisting those who are perceived as difficult.

TheWrap has obtained a spreadsheet of more than 400 “2025 Blacklisted Freelancers,” as the document is titled. When questioned about this, Valnet declined to comment. In an internal email accidentally forwarded to TheWrap, a Valnet executive said to another, “our documents are being leaked.”

The list is a remarkable catalogue of criticism or perceived misconduct tracked meticulously. “Applied to Screen Rant and went to Twitter with the rates,” one entry says. Another freelancer was blacklisted for “creating drama” by “discouraging a past writer from returning,” while others faced a Valnet ban for calling rates “abysmal” or requesting transparency. One freelancer who suggested Valnet include payment information in job listings was permanently banned. (TheWrap has blacked out the writers’ names.)

Other criticisms cited on the spreadsheet: “extremely rude and aggressive with hiring associate over rates and demanded a salary job”; “Combative, rude and argumentative with HR over pay”; and “Poor attitude, created drama via Writers Google Group email chain by discouraging a past writer from returning — speaking poorly about Screen Rant editorial team and company as a whole while being an active writer.”

A spokesman for Valnet said he was unavailable for comment because he was on vacation.

An M&A executive reached out to TheWrap saying the company would not be subject to “coercion” in responding, but did not respond to any specific questions.

“I’d like to bluntly ask you: What is Umberto trying to achieve?” asked head of M&A Rony Arzoumanian in an email. “Valnet invests tens of $millions in content, annually. We support journalism and would gladly welcome your questions.” He did not respond to further emails or phone calls.

“Valnet doesn’t care about exclusivity or quality,” said an insider familiar with digital publishing. “They arbitrage web traffic. They chase keywords in the same way day traders chase stocks. It’s quick gains over actual content. Their strategy treats digital content like a commodity. They flood the market with stories optimized for clicks rather than insight or originality.”

From foosball to digital porn empire

Hassan Youssef may be little-known in the clubby world of entertainment, and there’s a good reason for that. A civil engineer by training, he ventured into content creation after exiting an online porn business that he successfully built with his brother Sam and others, but that ended with a $6 million seizure of their funds by the Secret Service for alleged money laundering in 2009 before paying a $2.2 million fine.

The origins of Valnet can be traced back to Montreal’s competitive foosball circuit, according to a 2011 New York Magazine investigative report titled, “The Geek-Kings of Smut.”

In 2003, while still students, foosball players Matt Keezer, Stephane Manos, Sam Youssef and his brother Hassan decided to get into the world of online porn. Together, they started their first websites, with names like Jugg World, Ass Listing, KeezMovies and XXX Rated Chicks.

“We started with $5,000, and we grew the company … Everything happened gradually. We had a little money, we reinvested it,” Sam Youssef told The Montreal Journal last year.

Their venture proved hugely profitable. The group rapidly expanded, creating their own affiliate network (Jugg Cash) and their own paysite, Brazzers — named after a private joke, a “throaty immigrant-Arabonics version of ‘brothers,'” according to the report.

The company went from 80 employees in 2007 to 250 by 2009. Sam Youssef emerged as the business visionary, while Manos handled sales and motivation. Hassan did analytics. Keezer became a wizard of algorithms and Search Engine Optimization (SEO), helping their websites dominate search for adult keywords. It was their mastery of SEO that would help them later, as they expanded to more outwardly legitimate fan sites, helping their sites consistently rank at the top of Google searches.

Under the Brazzers brand, the company would develop a reputation for high quality productions, outsourcing the content creation for the websites to porn producers in Los Angeles, Las Vegas and Miami. The founders maintained a low profile and stayed under the radar amid their growing success.

They operated through a complex web of corporate entities, with the main business housed under the name “Mansef” — a combination of the names Manos and Youssef. In January 2007, Keezer bought the domain name pornhub.com for $2,750 and went online through a separate company called Interhub. The Brazzers group were silent partners.

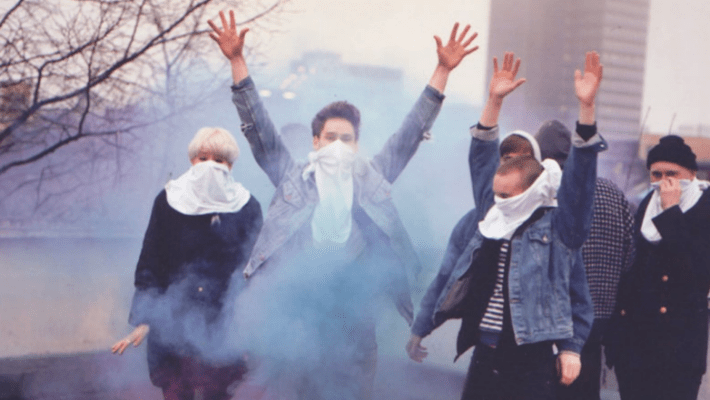

But Interhub ran into trouble in 2009 when British teenager Rose Kalemba discovered her rape as a 14-year-old broadcast on Pornhub. Kalemba pleaded to have the content removed for over six months, but was ignored. Kalemba’s rape was viewed over 400,00 times.

“The titles of the videos were ‘teen crying and getting slapped around’, ‘teen getting destroyed’, ‘passed out teen’. One had over 400,000 views,” Rose told the BBC. “The worst videos were the ones where I was passed out. Seeing myself being attacked where I wasn’t even conscious was the worst.” The video was finally removed after Kalemba set up a new email address posing as a lawyer and sent Pornhub an email threatening legal action.

By 2009, before they drew the attention of federal investigators, the Montreal-based enterprise had grown into one of the largest adult entertainment operations online, with the founders maintaining offices in both Canada and the United States. Their success in adult entertainment would ultimately provide the capital and the SEO playbook that Hassan Youssef would eventually apply a few years later in his pivot into mainstream digital media publishing.

Federal investigation and corporate transformation

In October 2009, the U.S. Secret Service’s Organized Fraud Task Force seized $6.4 million from two Mansef bank accounts, according to New York magazine. Federal investigators uncovered over $9 million in wire transfers from Israel, and the feds said that had been wired into the two accounts over a three-month period from banks in Israel and other countries on financial-fraud watch lists. Of the $6.4 million that was seized, the government returned $4.15 million and $2.2 million of the sum was forfeited in a settlement filed with the court.

In March 2010, the founders decided to get out of online porn and sold their adult entertainment assets to German businessman Fabian Thylmann, who paid $140 million for Pornhub.com and its related properties including Brazzers, according to Celebrity Net Worth.

Thylmann changed the company’s name from Mansef to Manwin, but the Youssef brothers were out.

From adult entertainment to entertainment media

After selling Mansef in 2010, Hassan and Sam Youssef took some time off before launching new ventures. They founded Valnet in August 2012. By 2015, after losing money investing in gyms and real estate, Sam Youssef founded Valsoft Corporation, focusing on acquiring and improving existing software companies.

Despite making their fortune in online porn, the Youssef brothers have scrubbed any mention of Mansef or their adult entertainment origins from their public personas of the Valnet site.

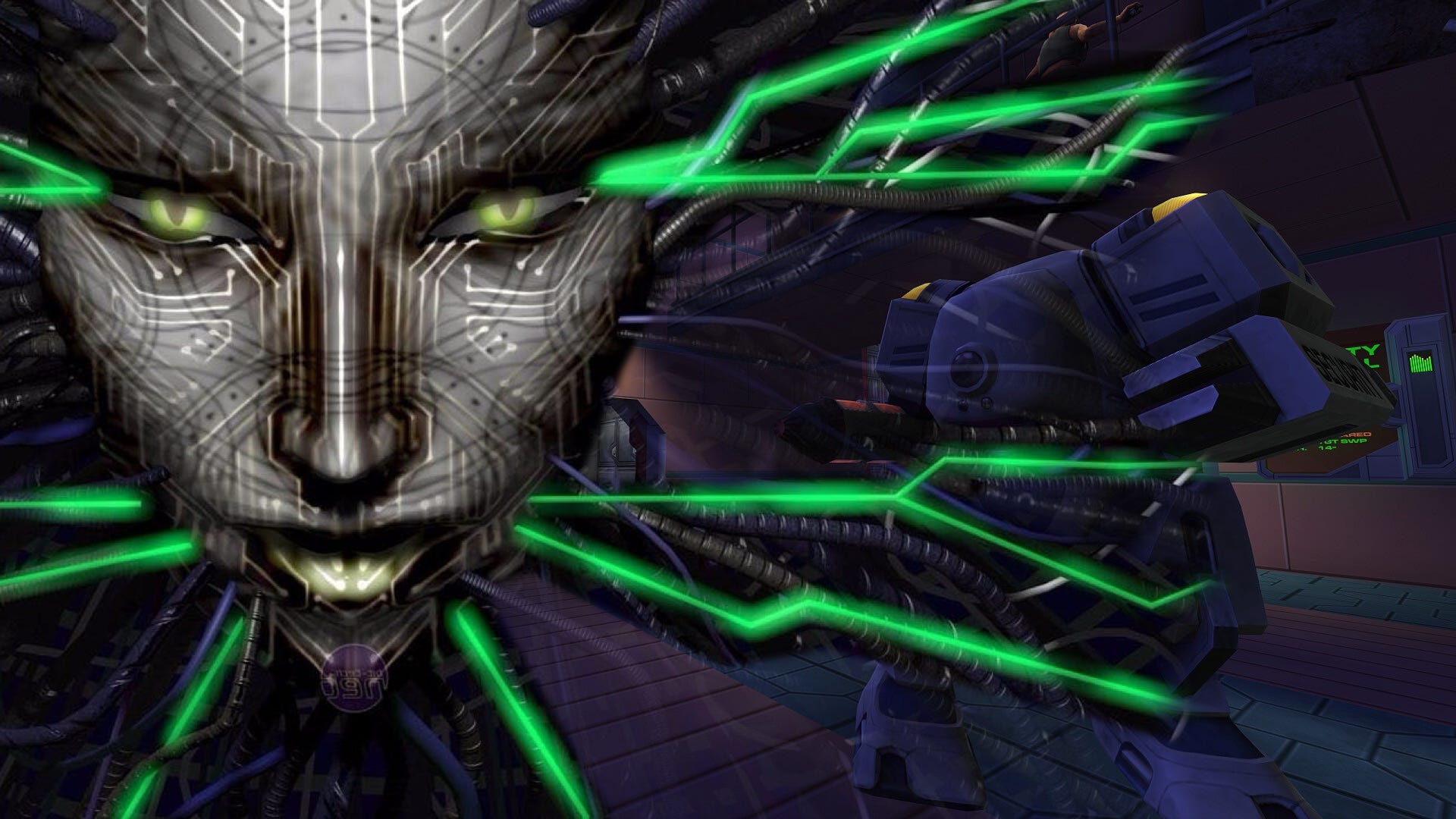

The Valnet sites serve passionate fans of film, television, video games and comics and need major scale traffic to make money off programmatic advertising.

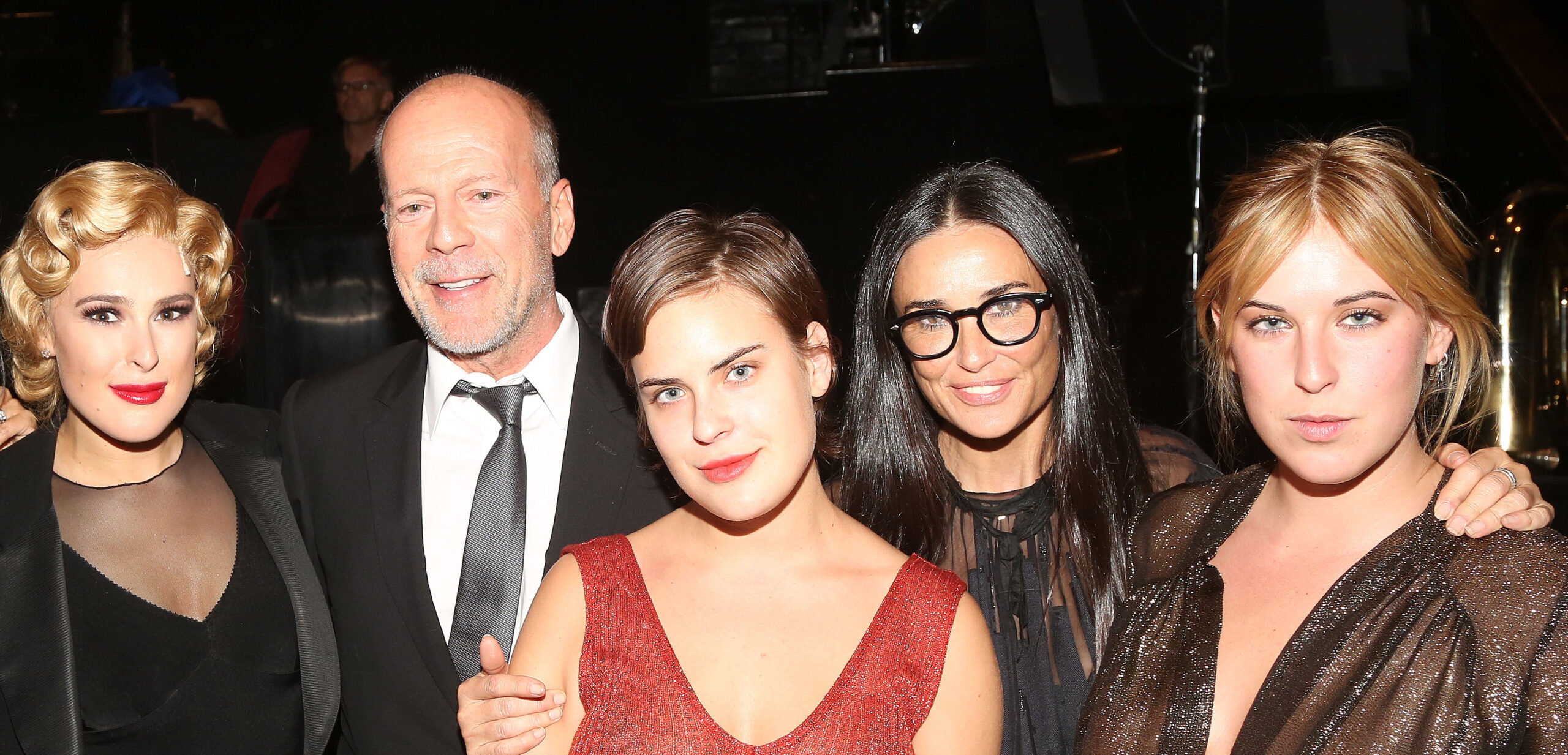

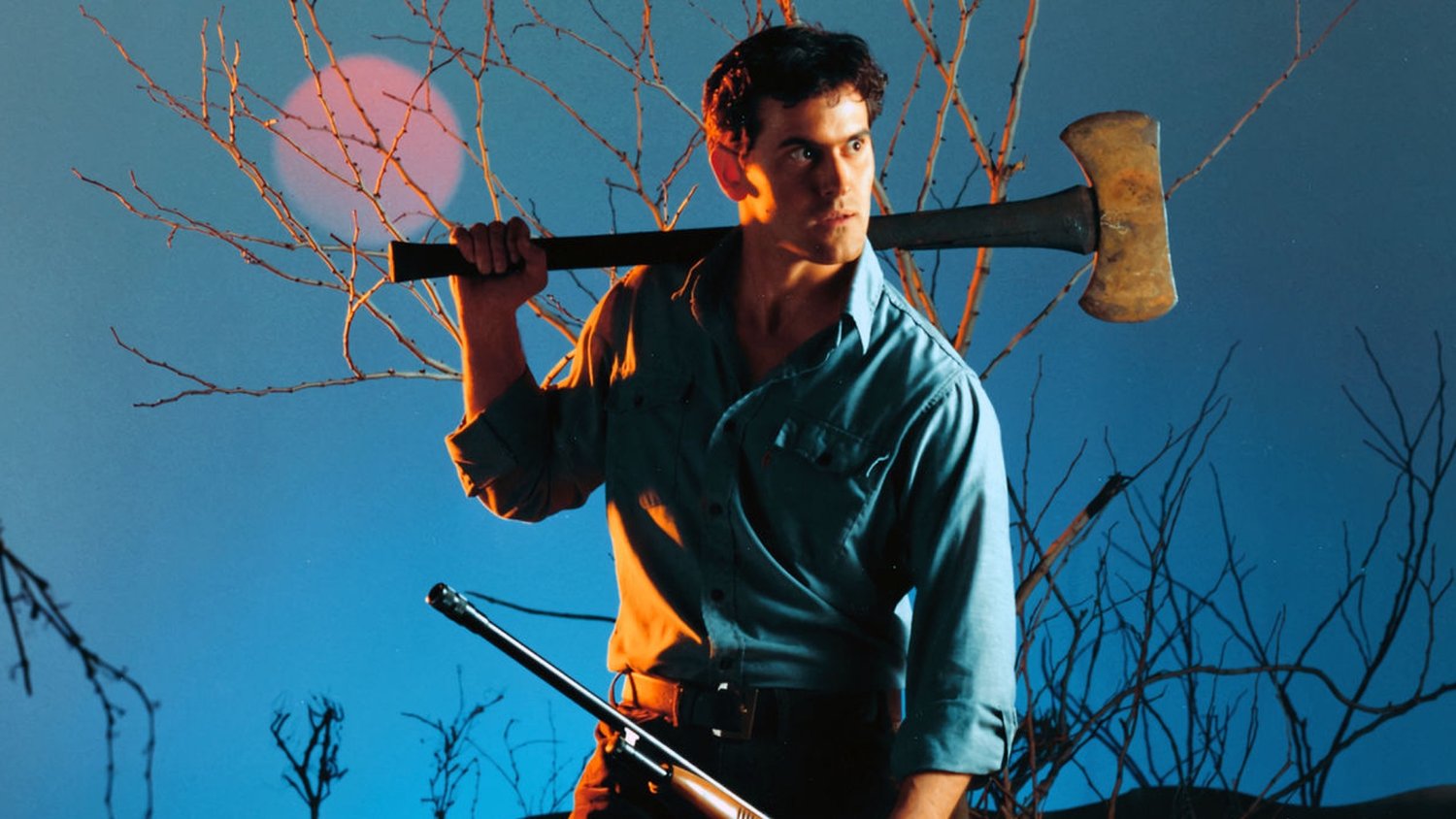

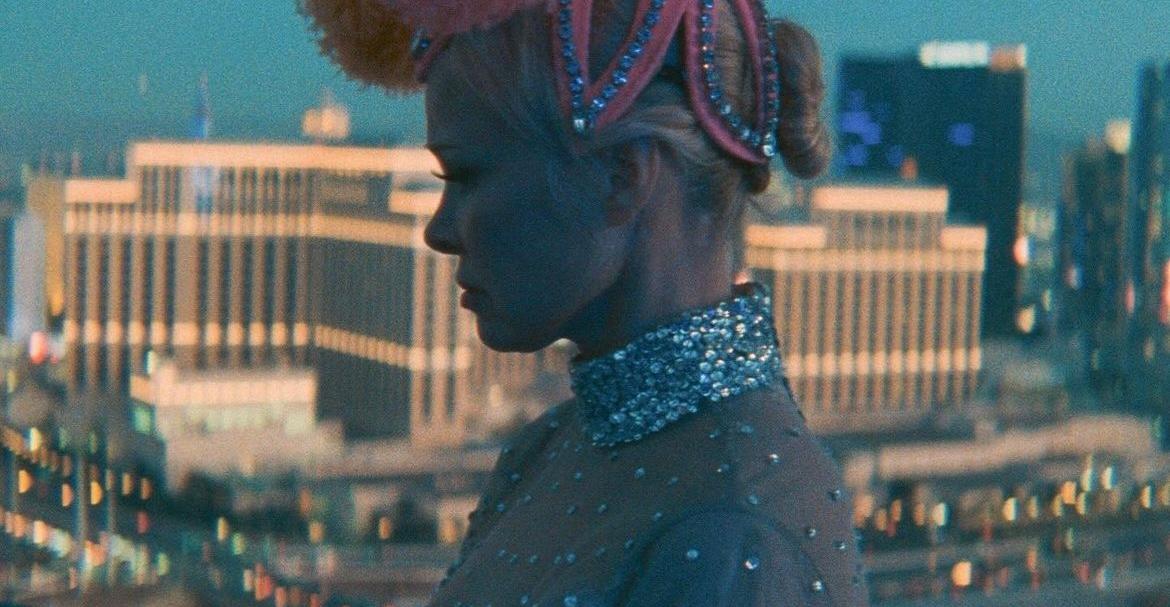

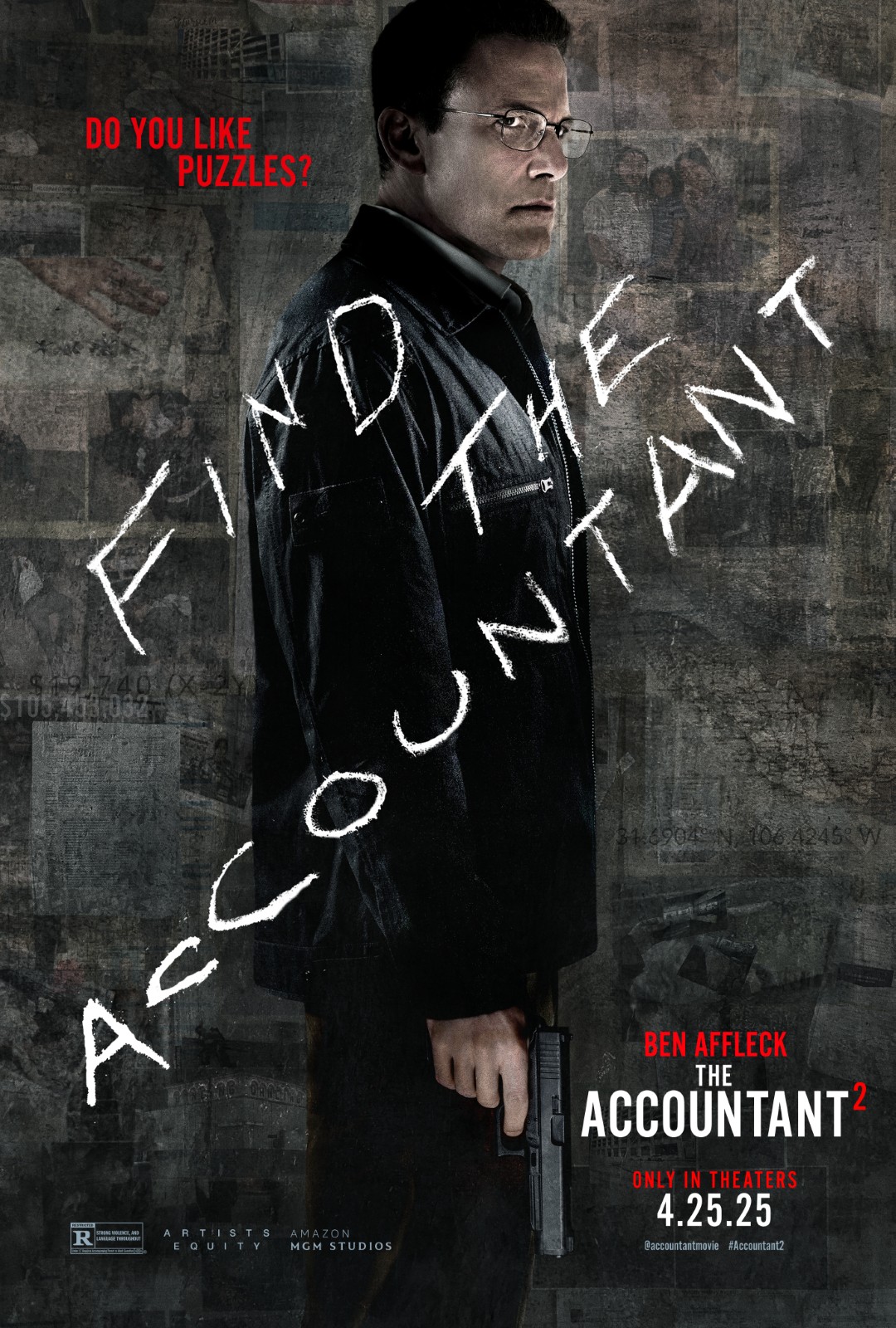

Remnants of the movie blog heydays of the late 2000s and 2010s when sites like Ain’t It Cool News made a mark, these Valnet-owned websites largely serve as fan-focused aggregation, commentary and listicle repositories focused on movies, TV, comic books and gaming. Many articles are designed to maximize consumer engagement (and fervent agreement or disagreement) with purposefully inflammatory headlines like “Arnold Schwarzenegger’s Perfect Replacement as the Terminator Is So Obvious, I Can’t Believe It Hasn’t Happened Yet.”

The current state of these websites reflect a Valnet playbook to maximize clicks and revenue. Once acquired, rates for freelancers at some of these sites dropped from $150 for reviews to $40, according to multiple freelancers who spoke to TheWrap. The current rate for reviews is now even lower at $30. Access to health insurance and benefits evaporated as full-time employees were rehired as at-will contractors, they said.

“I had written for Collider a couple of times prior to its Valnet acquisition, at a time when the freelance rate I was paid was $250 an article,” a former contributor said. “But soon after Valnet got involved, that rate dropped to $40.”

Content creators allege exploitation

According to another former contributor, Collider maintains “a content mill, borderline like almost sweatshop-level” where hundreds of writers are “constantly being pushed to write more, to do it quicker,” while editors face “pretty high level of quotas” despite being understaffed. The former contributor also alleged a pattern of firing employees who questioned company practices and recalled being called into a meeting where the individual was told “you should quit if you think it’s so bad here.”

In an interview with TheWrap, former Valnet writer Stephanie Ann Grant detailed her experience working for Valnet’s “The Travel” vertical. After accepting a contract for $30 per published article on Oct. 3, 2024, Grant described being suddenly locked out of Valnet on Oct. 23, 2024. She received no response from editors for six hours before getting an email announcing the termination of her contract.

“I then emailed the head of HR and then Valnet’s legal department. It appeared that Valnet had ghosted me,” Grant said. When her first paycheck failed to arrive on Nov. 1, Grant says her emails went unanswered for days until she received excuses that “it didn’t go through.”

Only after posting about her experience on LinkedIn did she receive payment — though she said she was still shorted $65.

“I checked my PayPal account settings to make sure it wasn’t a problem on my end, and as a freelance writer, this was the only time I’ve ever had someone having a ‘problem’ paying me,” Grant said.

Valnet declined to respond to questions about Grant’s experience.

According to the legal complaint filed by former MovieWeb writer Daniel Quintiliano, writers must submit to “Valnet’s complete and total discretion as to approval or revision of the work product” — a level of oversight that the lawsuit argues is inconsistent with independent contractor status under California law. The lawsuit details that Quintiliano regularly produced about three to four MovieWeb articles per day, five days or more per week, spending approximately two to three hours per article. Despite the intensive workload, he was paid only $15 per article with no additional compensation.

Valnet continues to aggressively expand its portfolio of consumer-facing websites, sending acquisition inquiries and seeking legal releases from freelancers while CEO Hassan Youssef remains largely behind the scenes.

The former Collider contributor said: “In journalism, there are really bad jobs. And then there is a place like Valnet,” adding it’s “one of the worst places that I’ve ever worked and is probably one of the worst journalism publications I’ve ever seen.”

The post Valnet Blues: How Online Porn Pioneer Hassan Youssef Built a Digital Media ‘Sweatshop’ appeared first on TheWrap.

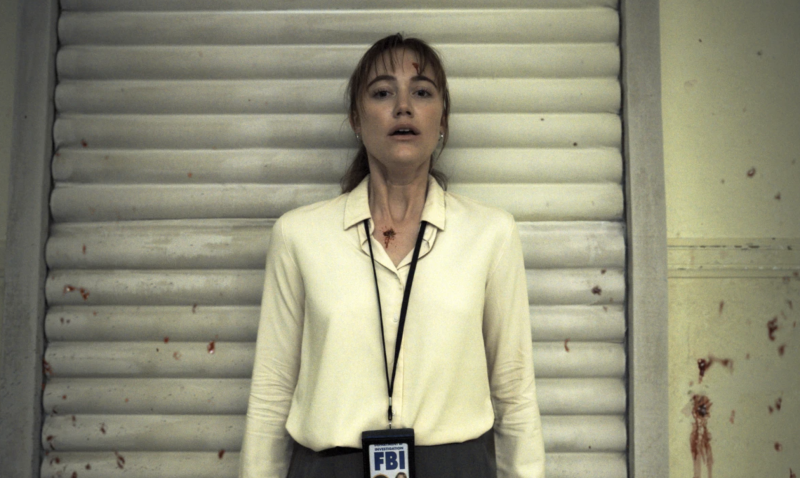

![First Dev Diary for ‘Cronos: The New Dawn’ Showcases Gameplay Mechanics and More [Video]](https://bloody-disgusting.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/cronos.jpg)

![‘FBC: Firebreak’ Coming in Summer 2025, New Gameplay Trailer Revealed [Watch]](https://bloody-disgusting.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/fbcfirebreak.jpg)

![Bloober Team and Skybound Entertainment Announce ‘I Hate This Place’ Game Adaptation [Trailer]](https://bloody-disgusting.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/ihatethisplace.jpg)

![‘System Shock 2: 25th Anniversary Remaster’ Infects PC and Consoles on June 26 [Trailer]](https://bloody-disgusting.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/sysshock2.jpg)

.png?format=1500w#)

![Arresting Images [THE BLOODY CHILD]](http://www.jonathanrosenbaum.net/wp-content/uploads/2010/12/the-bloody-child.jpg)

![‘Andor’: Tony Gilroy Teases More Romance, Season 2 Guests, Additional ‘Rogue One’ Characters & More [Interview]](https://cdn.theplaylist.net/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/20133148/tony-gilroy-andor-season-2.jpg)

![Elizabeth Olsen Says She’s Pitched A “Gnarly” White-Haired Wanda Returning To Marvel 50 Years Later [Exclusive]](https://cdn.theplaylist.net/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/20121325/Elisabeth-Olsen-WandaVision-Wanda-Scarlet-Witch.jpg)

![Delta Passenger Given Vomit-Covered Seat—Then The Flight Attendant Handled It In The Worst Place Possible [Roundup]](https://viewfromthewing.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/a321neogalley.jpg?#)

![Release: Rendering Ranger: R² [Rewind]](https://images-3.gog-statics.com/48a9164e1467b7da3bb4ce148b93c2f92cac99bdaa9f96b00268427e797fc455.jpg)

![[Podcast] Should Brands Get Political? The Risks & Rewards of Taking a Stand with Jeroen Reuven Bours](https://justcreative.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/jeroen-reuven-youtube-1.png)

![[Podcast] Should Brands Get Political? The Risks & Rewards of Taking a Stand with Jeroen Reuven](https://justcreative.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/jeroen-reuven-youtube.png)