The Americans: On “Henry Fonda for President”

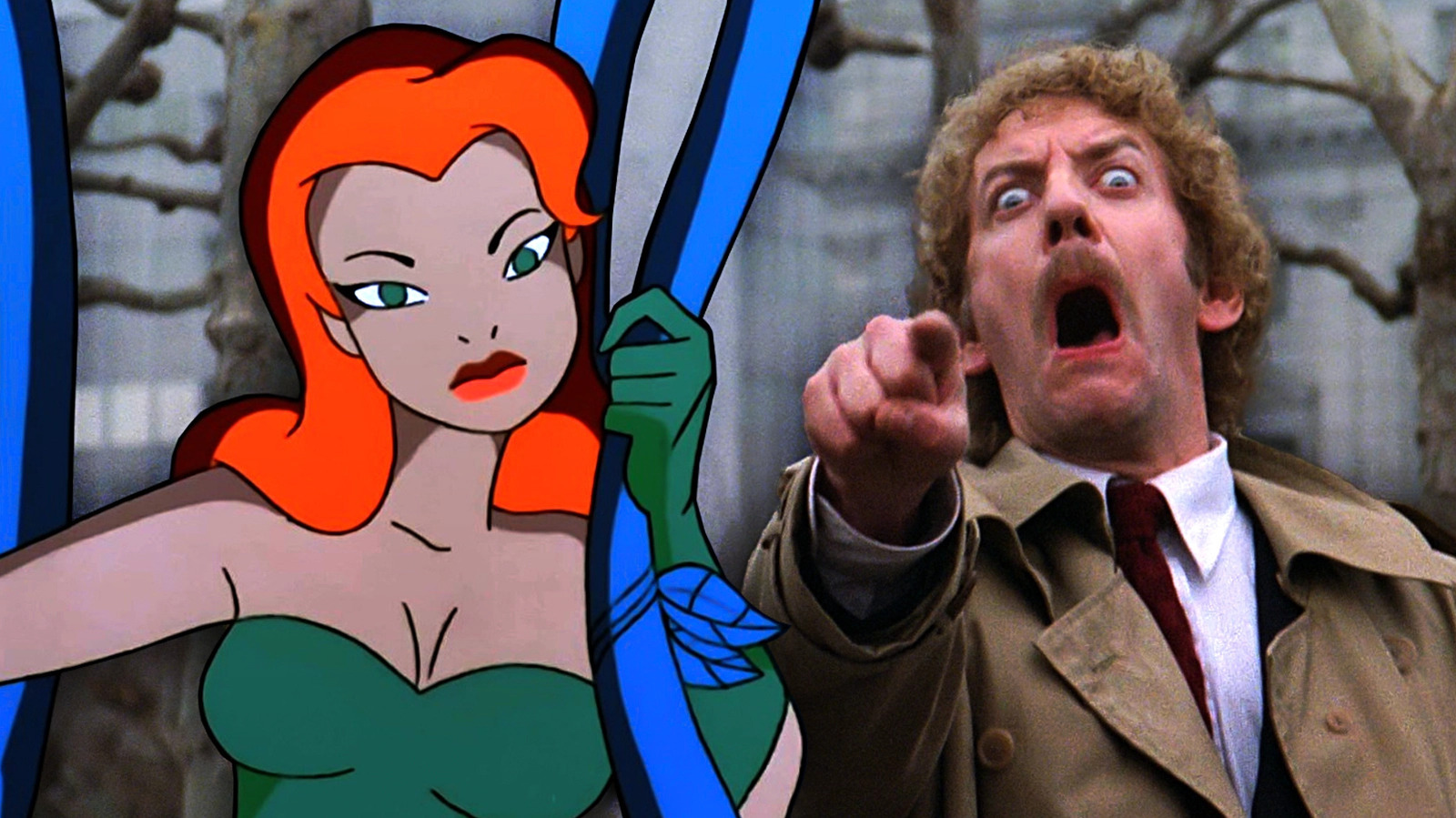

Henry Fonda for President (Alexander Horwath, 2024). From Fail Safe (Sidney Lumet, 1964).“What America needs is a kind of self-demystification,” muses Alexander Horwath in his new documentary, Henry Fonda for President (2024). Horwath, an Austrian film historian and curator, believes this can be accomplished through the medium of Henry Fonda. He sees Fonda, in a decidedly concrete and nonmystical way, as America itself. To prove that thesis, Horwath has filmed an essay, not a biography, and his approach is deliberately eccentric. His own feelings about the US—what its history, principles, and delusions look like to an outsider’s eyes—are at least as much a part of this three-hour film as Fonda is.Horwath, though a deep admirer of Fonda, is not a conventional “fan.” He has no use for “TCM Remembers”–type tropes, even the ones audiences most expect, such as identifying costars; either you recognize John Carradine, Vera Miles, or young Anthony Quinn, or you don’t. Fonda’s personal life is both there, via children Peter and Jane, and not there—Fonda had five marriages, but two are skipped, as is his enduring friendship with James Stewart. The emphasis is on the critical approach, and Horwath—who for 30 years ran the Viennale film festival and the Austrian Film Museum before making this, his first film—treats the films with respect. The clips from Fonda’s filmography are given enough time for us to see the actor at work, the ebb and flow of his long career, the different qualities he had in youth, middle age, and later in life.Lavish use is made of a Playboy interview with Fonda, recorded by Lawrence Grobel, who spent two hours a day at the actor’s home in Bel Air over the course of a week, accumulating about 12 hours of audio. It was the summer of 1981, and Fonda’s heart problems had worsened; everyone knew he was dying. It was Jane who convinced her father to do the interview, on the grounds that he owed it to himself and to posterity. Thus persuaded, Fonda still rarely sounds as though he wants to be doing this. The rasp of illness had all but erased his familiar twang, and the long pauses in his speech are up to the listener to parse. Caution about sensitive topics? Simple exhaustion? Here and there, maybe a decision to lie?The films are covered in roughly chronological order, though Horwath seems to enjoy going back to earlier scenes sometimes, as if to say “See? I told you so.” Horwath tackles John Ford’s epic Drums Along the Mohawk (1939) early on, having determined that Fonda is playing his own Dutch ancestor who settled in Upstate New York. Ford, says Horwath, “repeatedly sees figures of American history in Henry Fonda,” thus so do audiences to this day. Drums, filmed in Technicolor, is one of the most beautiful films of the 1930s. It is also ideologically thorny, to say the least, which makes Fonda’s presence its own kind of problematic. In this stage of his career, the actor radiated integrity in every role. Bringing that quality to a man whose desire for home means “extracting” (Horwath’s term) Indigenous people from theirs is a strange and uncomfortable thing to watch. Henry Fonda for President (Alexander Horwath, 2024). From Drums Along the Mohawk (John Ford, 1939).Born in Omaha, Nebraska, Fonda was a salesman’s son, with an upbringing as heartland as it gets, a distinction that connotes brutality as well as nostalgia. Fonda recounts how, at age 14, he and his father watched from the window of an office building as a mob attacked and lynched a Black man, Will Brown, in the street below. Horwath shows the archival photos in all their horror. Fonda believed his father, a liberal in a town of reactionaries, made him watch the riot to show where bigotry and intolerance could lead. If so, it worked. For the rest of his life, Fonda loathed violence and campaigned for justice, and chose roles that reflected both qualities.Such characters could take many forms. There was Fonda’s immortal Tom Joad in The Grapes of Wrath (1940), looking around the ramshackle transient camp and remarking drily, “They don’t look none too prosperous.” For Fritz Lang, Fonda essayed one of the first doomed-couple-on-the-lam films with You Only Live Once (1937); for John Ford, Fonda overcame his initial reluctance and played Young Mr. Lincoln (1939), in which the future president manages to stop a lynching. Horwath takes his time going over Fonda’s work in The Wrong Man (1956), an unusually somber film by Alfred Hitchcock about the cold indifference of American justice to those on the margins. Fonda’s soft-spoken cowboy in The Ox-Bow Incident (1943) tragically winds up a self-loathing witness to yet another lynching. It was a film that Fonda fought to get made and one that remained close to his heart. But his only film as producer was 12 Angry Men (1957), in which Fonda’s white-suited Juror No. 8 fights to prevent another killing, this time a judicial one. Henry Fonda for President (Alexander Horwath, 2024).Against the unusual th

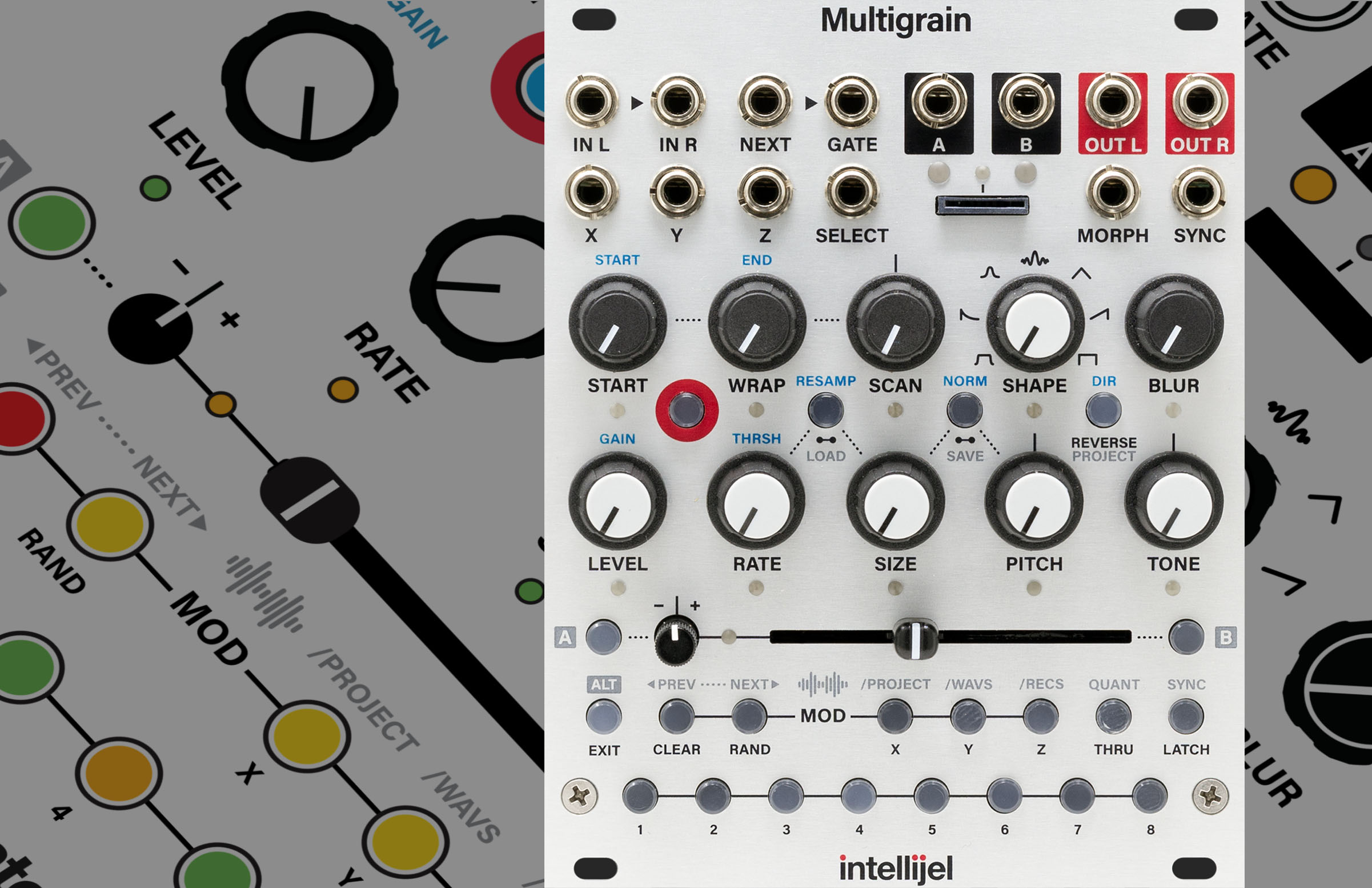

Henry Fonda for President (Alexander Horwath, 2024). From Fail Safe (Sidney Lumet, 1964).

“What America needs is a kind of self-demystification,” muses Alexander Horwath in his new documentary, Henry Fonda for President (2024). Horwath, an Austrian film historian and curator, believes this can be accomplished through the medium of Henry Fonda. He sees Fonda, in a decidedly concrete and nonmystical way, as America itself. To prove that thesis, Horwath has filmed an essay, not a biography, and his approach is deliberately eccentric. His own feelings about the US—what its history, principles, and delusions look like to an outsider’s eyes—are at least as much a part of this three-hour film as Fonda is.

Horwath, though a deep admirer of Fonda, is not a conventional “fan.” He has no use for “TCM Remembers”–type tropes, even the ones audiences most expect, such as identifying costars; either you recognize John Carradine, Vera Miles, or young Anthony Quinn, or you don’t. Fonda’s personal life is both there, via children Peter and Jane, and not there—Fonda had five marriages, but two are skipped, as is his enduring friendship with James Stewart. The emphasis is on the critical approach, and Horwath—who for 30 years ran the Viennale film festival and the Austrian Film Museum before making this, his first film—treats the films with respect. The clips from Fonda’s filmography are given enough time for us to see the actor at work, the ebb and flow of his long career, the different qualities he had in youth, middle age, and later in life.

Lavish use is made of a Playboy interview with Fonda, recorded by Lawrence Grobel, who spent two hours a day at the actor’s home in Bel Air over the course of a week, accumulating about 12 hours of audio. It was the summer of 1981, and Fonda’s heart problems had worsened; everyone knew he was dying. It was Jane who convinced her father to do the interview, on the grounds that he owed it to himself and to posterity. Thus persuaded, Fonda still rarely sounds as though he wants to be doing this. The rasp of illness had all but erased his familiar twang, and the long pauses in his speech are up to the listener to parse. Caution about sensitive topics? Simple exhaustion? Here and there, maybe a decision to lie?

The films are covered in roughly chronological order, though Horwath seems to enjoy going back to earlier scenes sometimes, as if to say “See? I told you so.” Horwath tackles John Ford’s epic Drums Along the Mohawk (1939) early on, having determined that Fonda is playing his own Dutch ancestor who settled in Upstate New York. Ford, says Horwath, “repeatedly sees figures of American history in Henry Fonda,” thus so do audiences to this day. Drums, filmed in Technicolor, is one of the most beautiful films of the 1930s. It is also ideologically thorny, to say the least, which makes Fonda’s presence its own kind of problematic. In this stage of his career, the actor radiated integrity in every role. Bringing that quality to a man whose desire for home means “extracting” (Horwath’s term) Indigenous people from theirs is a strange and uncomfortable thing to watch.

Henry Fonda for President (Alexander Horwath, 2024). From Drums Along the Mohawk (John Ford, 1939).

Born in Omaha, Nebraska, Fonda was a salesman’s son, with an upbringing as heartland as it gets, a distinction that connotes brutality as well as nostalgia. Fonda recounts how, at age 14, he and his father watched from the window of an office building as a mob attacked and lynched a Black man, Will Brown, in the street below. Horwath shows the archival photos in all their horror. Fonda believed his father, a liberal in a town of reactionaries, made him watch the riot to show where bigotry and intolerance could lead. If so, it worked. For the rest of his life, Fonda loathed violence and campaigned for justice, and chose roles that reflected both qualities.

Such characters could take many forms. There was Fonda’s immortal Tom Joad in The Grapes of Wrath (1940), looking around the ramshackle transient camp and remarking drily, “They don’t look none too prosperous.” For Fritz Lang, Fonda essayed one of the first doomed-couple-on-the-lam films with You Only Live Once (1937); for John Ford, Fonda overcame his initial reluctance and played Young Mr. Lincoln (1939), in which the future president manages to stop a lynching. Horwath takes his time going over Fonda’s work in The Wrong Man (1956), an unusually somber film by Alfred Hitchcock about the cold indifference of American justice to those on the margins. Fonda’s soft-spoken cowboy in The Ox-Bow Incident (1943) tragically winds up a self-loathing witness to yet another lynching. It was a film that Fonda fought to get made and one that remained close to his heart. But his only film as producer was 12 Angry Men (1957), in which Fonda’s white-suited Juror No. 8 fights to prevent another killing, this time a judicial one.

Henry Fonda for President (Alexander Horwath, 2024).

Against the unusual thematic consistency of Fonda’s roles, Horwath sets American history itself, reaching back to Fonda’s Dutch colonial roots and forward to just before his death in 1982, as the Reagan era gathered steam. Anchoring past to the present is Horwath’s own Fonda-linked travelogue, made with an attitude that’s part Alexis de Toqueville and part Louis Theroux. Horwath visits the Upstate New York village of Fonda (just take the Henry Fonda Memorial Highway); the building where the actor was born in Grand Island, Nebraska, since moved to the grounds of a museum in town; and the Christian Science church he attended in Omaha. Horwath journeys to the publicly managed migrant camp once used as a set in John Ford’s version of The Grapes of Wrath, talks to the women who preserve its past, and observes the Mexican laborers who now live in the modernized housing. There’s a deadpan tour of Tombstone, Arizona, the setting of another Ford masterpiece, My Darling Clementine (1946), whose existence is now entirely devoted to recreating the mythical past.

Those road-trip moments in the film’s leisurely running time have strong ties to the “Fonda Is America” theme. At other times Horwath uses a more tenuous Fonda connection to bring up something he clearly just wants to discuss, such as Taxi Driver (1976), a film that Horwath first relates to his subject via Travis Bickle’s “Mohawk” haircut; or Strange Victory (1948), an independent left-wing documentary that condemns the treatment of Black veterans (and promotes the candidacy of Henry Wallace). The latter film, directed by the blacklisted Leo Hurwitz, is used to belittle Fonda’s broken friendships during the age of HUAC; “such are the mild sacrifices made by liberals” is Horwath’s acid comment. This hardly seems fair, especially when Horwath skirts Fonda’s self-imposed exile from Hollywood to Broadway during the period. His principled absence lasted seven years, arguably among his last as a Hollywood-style leading man.

At other times, however, these loose fragments enrich the film in ways that aren’t spelled out in Horwath’s narration. More than once we’re treated to the windup of Ronald Reagan’s 1980 nomination speech, a fateful moment in US politics: “I’ll confess that I’ve been a little afraid to suggest what I’m going to suggest.” Reagan pauses, face scrunched up, swallowing hard, then adds, with a tiny quaver, “I’m more afraid not to.” A shorter, exquisitely timed pause, then “Can we begin our crusade, joined together in a moment of silent prayer?” It played like gangbusters in the arena and on TV, the prelude to Reagan’s landslide victory and the direction in which he took the country. Horwath uses the clip to show what he calls “the hubris that can emerge from utopia,” arguing that it is “only an aspiration.”

All true enough, but Reagan’s speech makes a different point too. It shows what Fonda meant when Grobel asks him, late in the movie, if Ronald Reagan is a good actor. Fonda responds with a hilariously sharp “No,” as if to slam the door on the very notion, and we’ve seen why. Reagan in that speech, whatever his personal beliefs, is indicating. This is the term actors use for someone performing calculated, surface gestures that tell the audience which emotion is being evoked. In Reagan’s case, we have the furrowed brow, the pauses, the feigned hesitation. Good acting is fundamentally interior; bad acting, indicating, is exterior. Contrasting Reagan with Fonda’s deep, fiery interiority makes it obvious what Fonda had as an artist, and what Reagan lacked. Not that it mattered when playing on a national stage. Indicating is a mortal sin in acting; in politics, it’s a way of life, and it works.

“We’re gonna be on that path”—Reagan’s path—“for a long time,” Fonda predicts to Grobel.

Henry Fonda for President (Alexander Horwath, 2024). From “Maude’s Mood,” Maude (season 4, episode 18, 1976).

Henry Fonda for President is admiring, but it is no hagiography. He was, said his children and even his friends, a hard man, closed off and difficult. Fonda acknowledges this more than once. Playing a part was a way of showing things he couldn’t bring out in real life, even if he wanted to. “You should understand,” he tells Grobel, “that I don’t like myself. I wish I was, you know, somebody better, smarter. But look at the chances I’ve had to play all these wonderful people, and I’ve been able to pretend I was those people.”

Bea Arthur, in a 1976 episode of the sitcom Maude (1972–78) that gives the documentary its name, latches onto Henry Fonda as the most natural choice there could be for what she wants in a president. Stoic, thoughtful, principled. Fonda, despite a lifetime of lending his name to liberal causes and candidates, told anyone who would listen, “That’s not me.” Horwath matches the reveal of Maude’s campaign poster with Fonda saying, “I know people speak of me as the typical American. Trustworthy, loyal, full of integrity and so on. I read it, but it doesn’t mean anything to me, and I’m not conscious of trying to be like that at all.” He didn’t have to be. Fonda came up during a time when such qualities were associated with Americans. Everyone always knew this was an ideal, not a reality. But it remained as an American self-image, a Fonda-like aspiration. At no point does Horwath say that image is gone. He doesn’t have to.

![‘I’ve Got 8 Chickens at Home Counting on Me’—Delta Pilot Calms Nervous Cabin With Bizarre Safety Promise [Roundup]](https://viewfromthewing.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/delta-cabin.jpg?#)

.png?#)