The Future Leaks Out: William S. Burroughs and the Cut-Up Film

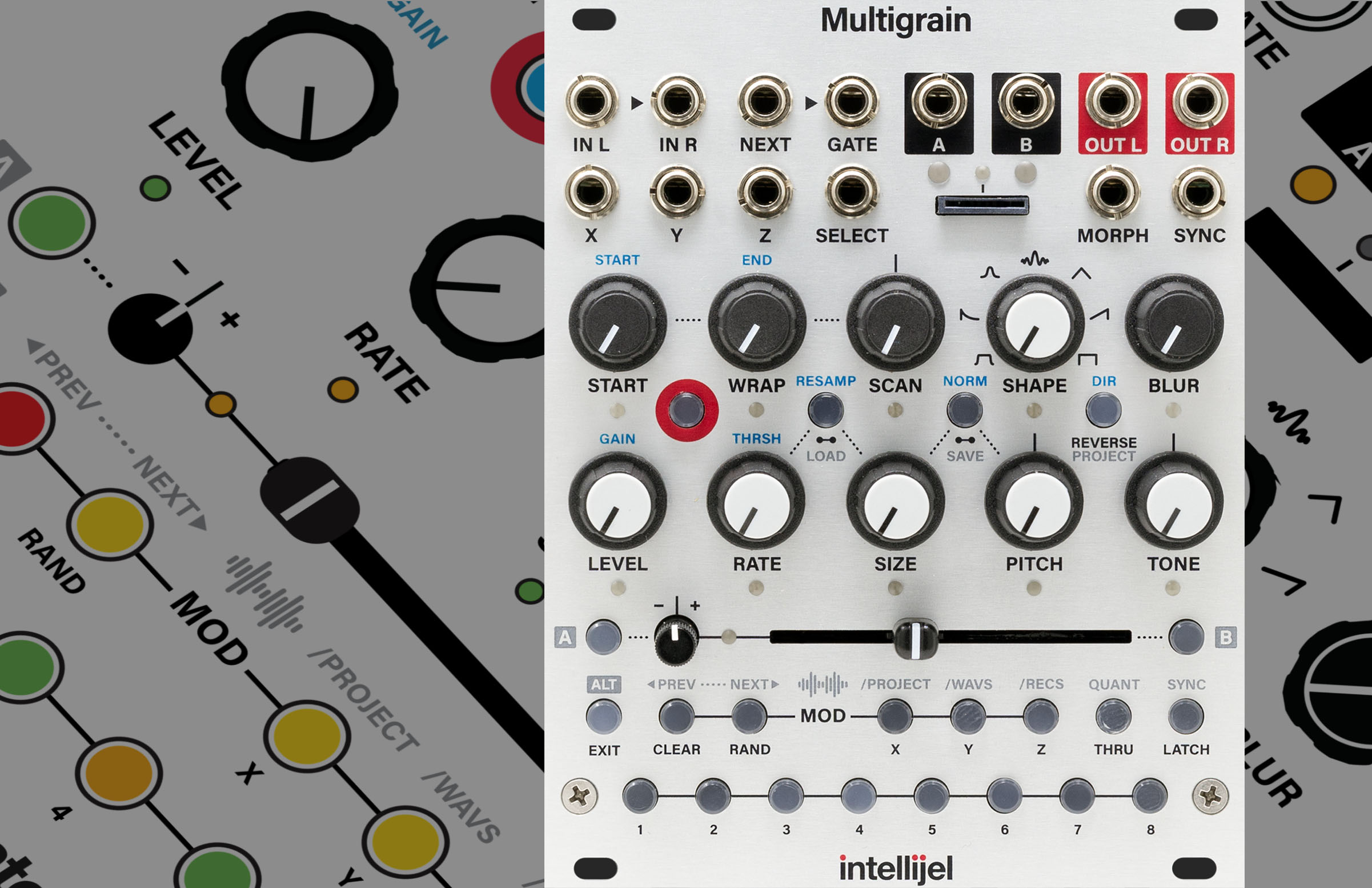

Luca Guadagnino’s Queer is now showing on MUBI in many countries.Queer (Luca Guadagnino, 2024).Anyone visiting William S. Burroughs in Paris while he edited his third novel would have found a scene closer to a bustling film-production office than a lonely writer’s retreat, with a storyboard on the wall and several collaborators beetling away. Burroughs composed Naked Lunch as a series of loosely related, nonchronological “routines”; the story was found in the edit as he rearranged these pieces into their final order. He had the help of friends such as Allen Ginsberg, Jack Kerouac, and the painter and poet Brion Gysin, who later recalled, “The raw material of Naked Lunch overwhelmed us. [...] Burroughs was more intent on Scotch-taping his photos together into one great continuum on the wall where scenes faded and slipped into one another than occupied with editing the manuscript.”1Gysin—having accidentally discovered what he and Burroughs would come to call the “cut-up” method when slicing through the old newspapers protecting a countertop workspace and becoming intrigued by the juxtaposition of scraps of stories from different editions—was by now applying a similar technique to audiotape recordings. With Gysin’s inspiration and collaboration Burroughs would develop variations on cut-ups across the 1960s, particularly in the novels The Soft Machine, The Ticket That Exploded, and Nova Express, using techniques such as slicing pages into quadrants and rearranging them like tangrams, or folding a page lengthwise and placing it atop another with the lines of text aligned. The composite page, featuring prose from earlier or later in the book, could then be inserted anywhere in the manuscript, simultaneously flashback and flash-forward. “Any narrative passage or any passage of poetic images is subject to any number of variations, all of which may be interesting and valid in their own right,” according to Burroughs, whose approach to prose in this period bears some resemblance to Soviet theories of montage, in which modular units of meaning are arranged and rearranged. “Cut-ups establish new connections between images.”2 The physical labor of the cut-ups, often involving cutting with a blade and resplicing with tape, is also analogous to analog film editing.Burroughs backed into filmmaking, developing a cinematic method for the production of prose works, and only later applying it to the production of actual moving images. In 1960, he met Antony Balch, a British expat in Paris, a colorful figure frequently described by his acquaintances as “camp.” Balch had been interested in filmmaking and film exhibition from an early age, projecting his work in the family living room as a child and selling tickets to his own parents. He was working in commercials and subtitling when he fell into Gysin’s orbit.3 Balch and Burroughs collaborated on a handful of films informed by Burroughs’s prose experiments; that the cut-up method was essentially cinematic is borne out by the fact that the Burroughs–Balch films fit so snugly within an experimental filmmaking zeitgeist characterized by collage and lysergic imagery. As well, Towers Open Fire (1963) and The Cut-Ups (1966), especially, align with other movements percolating in the artistic underground of the 1960s: revolutionary politics, sexual permissiveness, and esoteric spiritual and pharmaceutical practices. The cut-up films are liberatory in their implications, tuned into invisible currents. Per Burroughs: “Cut-ups put you in touch with something you know but don’t know that you know.”4Towers Open Fire (Antony Balch, 1963).Balch directed the nine-and-a-half-minute Towers Open Fire, for which Burroughs wrote the script and in which he stars in multiple roles, contributing to the film’s destabilizing and recombinant effect.The film includes a quick sequence of hands and papers in close-up, demonstrating the fold-in technique, followed by a longer sequence edited according to cut-up principles, with shots of Burroughs walking through Paris streets and quaysides. Cuts—initially every twelve frames, then speeding up—rearrange the footage into staccato blurts. The rest of the film is derived from sections of Burroughs’s recent novels; his voiceover opens with a racially provocative monologue from The Soft Machine (“Why don’t you straighten out and act like a white man?”). Other audio elements include Moroccan Sufi trance music, chants and incantations (accompanying footage of hands passing over stacks of film reels), medical jargon, and passages about the eleventh- and twelfth-century Islamic leader Hasan-i Sabbah, founder of the Order of Assassins, who is also invoked in Nova Express. The narrative, piecemeal as it is and punctured by random interruptions, coheres around intimations of collapse, with Pathé newsreels about the stock-market crash and scenes of a boardroom, where Burroughs is among the executive class erased in flickers of static, and of insurrection, with Burroughs in

Luca Guadagnino’s Queer is now showing on MUBI in many countries.

Queer (Luca Guadagnino, 2024).

Anyone visiting William S. Burroughs in Paris while he edited his third novel would have found a scene closer to a bustling film-production office than a lonely writer’s retreat, with a storyboard on the wall and several collaborators beetling away. Burroughs composed Naked Lunch as a series of loosely related, nonchronological “routines”; the story was found in the edit as he rearranged these pieces into their final order. He had the help of friends such as Allen Ginsberg, Jack Kerouac, and the painter and poet Brion Gysin, who later recalled, “The raw material of Naked Lunch overwhelmed us. [...] Burroughs was more intent on Scotch-taping his photos together into one great continuum on the wall where scenes faded and slipped into one another than occupied with editing the manuscript.”1

Gysin—having accidentally discovered what he and Burroughs would come to call the “cut-up” method when slicing through the old newspapers protecting a countertop workspace and becoming intrigued by the juxtaposition of scraps of stories from different editions—was by now applying a similar technique to audiotape recordings. With Gysin’s inspiration and collaboration Burroughs would develop variations on cut-ups across the 1960s, particularly in the novels The Soft Machine, The Ticket That Exploded, and Nova Express, using techniques such as slicing pages into quadrants and rearranging them like tangrams, or folding a page lengthwise and placing it atop another with the lines of text aligned. The composite page, featuring prose from earlier or later in the book, could then be inserted anywhere in the manuscript, simultaneously flashback and flash-forward. “Any narrative passage or any passage of poetic images is subject to any number of variations, all of which may be interesting and valid in their own right,” according to Burroughs, whose approach to prose in this period bears some resemblance to Soviet theories of montage, in which modular units of meaning are arranged and rearranged. “Cut-ups establish new connections between images.”2 The physical labor of the cut-ups, often involving cutting with a blade and resplicing with tape, is also analogous to analog film editing.

Burroughs backed into filmmaking, developing a cinematic method for the production of prose works, and only later applying it to the production of actual moving images. In 1960, he met Antony Balch, a British expat in Paris, a colorful figure frequently described by his acquaintances as “camp.” Balch had been interested in filmmaking and film exhibition from an early age, projecting his work in the family living room as a child and selling tickets to his own parents. He was working in commercials and subtitling when he fell into Gysin’s orbit.3 Balch and Burroughs collaborated on a handful of films informed by Burroughs’s prose experiments; that the cut-up method was essentially cinematic is borne out by the fact that the Burroughs–Balch films fit so snugly within an experimental filmmaking zeitgeist characterized by collage and lysergic imagery. As well, Towers Open Fire (1963) and The Cut-Ups (1966), especially, align with other movements percolating in the artistic underground of the 1960s: revolutionary politics, sexual permissiveness, and esoteric spiritual and pharmaceutical practices. The cut-up films are liberatory in their implications, tuned into invisible currents. Per Burroughs: “Cut-ups put you in touch with something you know but don’t know that you know.”4

Towers Open Fire (Antony Balch, 1963).

Balch directed the nine-and-a-half-minute Towers Open Fire, for which Burroughs wrote the script and in which he stars in multiple roles, contributing to the film’s destabilizing and recombinant effect.The film includes a quick sequence of hands and papers in close-up, demonstrating the fold-in technique, followed by a longer sequence edited according to cut-up principles, with shots of Burroughs walking through Paris streets and quaysides. Cuts—initially every twelve frames, then speeding up—rearrange the footage into staccato blurts. The rest of the film is derived from sections of Burroughs’s recent novels; his voiceover opens with a racially provocative monologue from The Soft Machine (“Why don’t you straighten out and act like a white man?”). Other audio elements include Moroccan Sufi trance music, chants and incantations (accompanying footage of hands passing over stacks of film reels), medical jargon, and passages about the eleventh- and twelfth-century Islamic leader Hasan-i Sabbah, founder of the Order of Assassins, who is also invoked in Nova Express. The narrative, piecemeal as it is and punctured by random interruptions, coheres around intimations of collapse, with Pathé newsreels about the stock-market crash and scenes of a boardroom, where Burroughs is among the executive class erased in flickers of static, and of insurrection, with Burroughs in goofy fatigues urging on militants armed with ping-pong guns. The otherwise black-and-white film ends with a figure played by Burroughs hanger-on Michael Portman looking skyward to see blotches of hand-painted color, à la Stan Brakhage, an ominous Atomic Age abstraction.

The startling juxtapositions and apocalyptic imagery place the film in conversation with Burroughs’s text (and multimedia) cut-ups of the era, as well as with the found-footage films of Bruce Conner, particularly A Movie (1958), in which mushroom clouds, firing squads, and Hindenburg crash footage combine for a bad-vibes-newsreel effect. Extended shots of Gysin’s Dreamachine—a spinning cylinder, with apertures at regular intervals and a light source in the center, said to induce a hypnagogic state—suggest the enchantment of proto-cinematic devices such as the Zoetrope, as well as the flicker films of Tony Conrad and drone compositions of John Cale.

Towers Open Fire (Antony Balch, 1963).

Towers Open Fire is confrontational and therefore consciousness-expanding, but not strictly a cut-up, which disappointed Gysin. More purely aleatory in its construction, The Cut-Ups is abrasive and abstract. Balch had planned a documentary called Guerilla Conditions, about Burroughs and Gysin, and collected footage of them at work at the so-called Beat Hotel in Paris’s Latin Quarter, where they, Ginsberg, and Gregory Corso lived, as well as at the Muniria Hotel in Tangier and the Hotel Chelsea in New York, and in the surrounding urban environments. Burroughs walks the streets, steps into a phone booth, and makes a call as the camera takes in Times Square movie marquees and signage; Gysin works on his calligraphic paintings.

Seen in its raw form, the footage might have resembled unstructured depictions of scenester mundanity à la Andy Warhol. Instead, it was edited into four linear reels, with the film constructed out of alternating one-foot sections from each reel, in a regular 1-2-3-4 sequence. As Balch later explained, “The actual chopping was done by a lady who was employed to take a foot from each roll and join them up. A purely mechanical thing, nobody was exercising any artistic judgement at all.” On the soundtrack, Burroughs and Gysin repeat a litany of anodyne phrases: “Yes, Hello?” “Look at that picture.” “How does it seem to you now?” “Where are we now?” “Does it seem to be persisting?” “Good. Thank you.” The phrases apparently come from a Scientology audit; Burroughs was deeply interested in Scientology at the time, particularly the principle of the reactive mind, the unconscious storehouse of toxic energy and traumatic memories, engrams, which could be cleared through repetition of negative phrases. The film is assembled like a musique concrète piece; Burroughs and Gysin repeated the phrases for exactly the length of the film, twenty minutes and four seconds. “I don’t know that it was necessarily the right length,” Balch later said. “I’ve shown the film at 16fps instead of 24, and it’s also very interesting.”5 Burroughs’s Beat bona fides and third-eye ethos connect him to the hippie mysticism of Harry Smith (who would soon begin work on the palindromic montage of No. 18: Mahagonny, 1970–80). The metrical editing scheme of The Cut-Ups is also closely related to the graphic cinema of Peter Kubelka; its deliberate constraints further recall the structural films of Hollis Frampton and others.

When considering an avant-garde art practice that prioritizes intuition or arbitrariness, it’s easier to discuss the conceptual implications of the process than the aesthetic revelations of the work itself. In this case, one might say that The Cut-Ups represents the death of the author, foreshadowing eras of postmodern collage and posthuman automation, or that its discontinuity is of a piece with the psychedelic age, and leave it at that. But the film’s content is not secondary to its form. The dense interweaving of images from across the urban environment, combined with some knowledge of the Burroughs mythology, makes the experience of watching the film haunted and uneasy.

The recurrent image, in The Cut-Ups, of a shirtless young man, his chest striped with light filtered through a Venetian blind, recalls the nude torso of Kiki de Montparnasse in Man Ray’s Return to Reason (1923), another experiment in montage derived from a non-filmic art practice, namely Ray’s “Rayographs”—cameraless photographic imprints. The unclothed figure in that film serves as an anchor, a moment of figuration at the end of a whirlwind of surrealism; it plays a similar role in the glitchy Cut-Ups, buthere, there are intimations of illicit queer desire. The intercutting takes on subliminal dimensions, like pangs of memory. Likewise, the shots of Burroughs on his urban ramblings, while echoing the Surrealist psychogeographic practice of the dérive, also suggest cruising. The frequent interruptions leave the viewer restless, paranoid, a state of awareness apt for contemplation of an author who wrote about gay sex, drugs, and other conspiracies carried out on the underside of society. This is necessarily a subjective reading, but triggering the viewer’s subjectivity is very much the work’s intention. Nevertheless the film’s influence is primarily formal: Nicolas Roeg, for one, was very taken with the cut-up technique, and consulted Balch about it when editing Performance (1970).

The Cut-Ups (Antony Balch, 1966).

Both Towers Open Fire and The Cut-Ups were made at a time when avant-garde film was a significant component of alternative performing-arts events, including Andy Warhol’s Exploding Plastic Inevitable. They were duly projected at early performances by bands such as Pink Floyd and Soft Machine, who had taken their name from Burroughs’s book, but they were also exhibited in mainstream theaters. Balch made an early foray into distribution when he exhibited Towers Open Fire on a bill with Tod Browning’s Freaks (1932), which had never previously received a release in the UK. Balch subsequently worked as a distributor and booker at several London cinemas, particularly the notorious Jacey Cinema at Piccadilly, where his program juggled arthouse and adult films, for which he designed many of the posters. He relished foisting his own films on unsuspecting audiences, who complained of headaches, and left an inordinate number of items behind in their rush to leave the theater, according to Gysin: “their handbags or their pants or their umbrellas or their shoes—an extraordinary number of unbelievable objects that they had never seen left behind before.” The Cut-Ups is only nineteen minutes long, but Balch later edited a twelve-minute version to placate the employees of one theater, who were sick of it. Despite featuring no explicit content that anyone noticed (there is a shot of Balch, shirtless from the waist up, in orgasmic ecstasy, but the censors may have been too confused to understand it), patrons complained that Towers Open Fire was “disgusting.” “It shows we’re really getting to them!” Balch enthused.6 Towers Open Fire eventually became the first British film with a U certificate to be reclassified as X.7

In a letter to Balch in 1968, Burroughs, in New York City after covering the Democratic National Convention in Chicago for Esquire, exulted in new radical possibilities, both political and pornographic: “The most interesting developments here are: real organized non communist resistance among both blacks and whites. And the complete breakdown of censorship. There are shops all over town [in New York City] where you can buy pictures of naked boys with hard ons.” The loosening of censorship around art throughout the 1960s—a process in which Burroughs played a large part as the author of Naked Lunch, the subject of a major First Amendment case—created a highbrow audience for films, artsy and otherwise, on taboo themes. Burroughs and Balch seem to have come fairly close to getting a film of Naked Lunch off the ground, though the money didn’t come together (blame Mick Jagger, who was interested but didn’t trust Balch to direct). In his novel The Wild Boys, involving a band of gay guerillas, Burroughs continued his experiments in montage across mediums. Passages he referred to as “abstracts” give neutral descriptions of multi-screen entertainments as if viewed in a “Penny Arcade Peep Show.” (The first sentence of the book: “The camera is the eye of a cruising vulture flying over an area of scrub, rubble and unfinished buildings on the outskirts of Mexico City.”)

Meanwhile, Balch distributed and exhibited softcore films and European art films, sometimes recutting and retitling the latter to appear as the former. (At one time, he had plans to release Au Hasard Balthazar [1966] under the title The Beast Is Not for Beating.) He explored his interest in the occult with the 1968 Witchcraft through the Ages re-edit of the silent classic Häxan (1922), featuring a voiceover by Burroughs, and finally directed his first feature in 1970. Cashing in on the sexploitation craze he had helped spearhead through his work in Soho grindhouses, Secrets of Sex is a profoundly eccentric, inventive, and very unsexy omnibus film narrated by a mummy. In one episode, a “strange young man” (Hollywood Babylon ghostwriter and fellow connoisseur of kink and black magick Elliott Stein) tries to bring a pangolin into the bedroom.

Bill and Tony (William S. Burroughs, 1972).

Burroughs and Balch also collaborated on Bill and Tony (1972), a five-minute film designed to be projected onto human faces. In it, Burroughs and Balch appear side by side, repeating, and then lip-synching, two text pieces aligned with their interests in the fetishistic, the bizarre, and the occult: an Scientology engram procedure, and the carnival barker's patter from the opening of Freaks. The “facial projection” effect, also used with tribal masks in Towers Open Fire, was inspired by Gysin, whose idea was to perform onstage while a nude photograph of himself was projected onto his clothes.

In September of 1964, Burroughs had enthusiastically described his idea for a similar effect: What if a photo of a street scene was overlaid atop the real scene such that “the photo fills the same space in the observer […] and naturally fits reality”? It would “cast yesterday shadows on today.” The cut-ups could also see into the future, Burroughs often claimed: “When you experiment with cut-ups over a period of time, you find that some of the cut-ups and rearranged texts seem to refer to future events [...] When you cut into the present the future leaks out [...].”8 This was proven true, after a fashion, after Balch’s 1980 death from cancer, aged just 42, robbed cinema of a rich character and cut short a fascinating career.

Ghosts at No. 9, completed in 2005, reuses and repurposes the Guerilla Conditions footage used in The Cut-Ups, as well as other footage set to be thrown out after Balch’s death. Genesis P-Orridge, who assembled the film, recalled receiving a call from Burroughs in New York, imploring them to rescue the reels from Balch’s office (which they did, after cashing a dole check to pay for the taxi).

Ghosts at No. 9 (Antony Balch and Genesis P-Orridge, 1982/2005).

One provocation of Burroughs and Balch’s methods is to obviate authorship. Yes, P-Orridge proves, someone else can generate an entirely new artwork by applying a new, random sequence to the same raw material. The first half of Ghosts at No. 9, especially, lives up to its title, with the Cut-Ups footage running in a different order, like a memory distorted over time. The second half, including footage shot by the German filmmaker Klaus Maeck after Balch’s death, plays with other avant-garde effects, including superimpositions, double-exposures, and extended close-ups of Burroughs’s left pinkie, which he cut off at the second knuckle during a Van Gogh–like episode of romantic obsession in the 1940s. Over time, the imagery grows more abstract, as if deteriorating. The soundtrack is derived from unreleased audio cut-ups Burroughs had allowed to be turned into the Industrial Records LP Nothing Here Now but the Recordings, as well as his dictated prose and industrial noise. Voiceover in the film’s final section draws from Burroughs’s “The Electronic Revolution,” in which he explains his idea that “illusion is a revolutionary weapon,” capable of disrupting the workings of power along organized mass-media channels through the proliferation of distorted and manipulated text and sound, in a process similar to the Situationist practice of détournement:

TO SPREAD RUMOURS Put ten operators with carefully prepared recordings out at rush hour and see how quick the words get around. People don't know where they heard it but they heard it. TO DISCREDIT OPPONENTS Take a recorded Wallace speech, cut in stammering coughs sneezes hiccoughs snarls pain screams fear whimperings apoplectic sputterings slobbering drooling idiot noises sex and animal sound effects and play it back in the streets subway stations parks political rallies. AS A FRONT LINE WEAPON TO PRODUCE AND ESCALATE RIOTS There is nothing mystical about this operation. Riot sound effects can produce an actual riot in a riot situation.

This reads today like a very prescient description of a modern digital-media ecosystem permanently on information-warfare footing. Burroughs had conceived of the cut-ups as radical, and democratizing: “anyone with a pair of scissors could become a poet.” Today, you can do it without the scissors—though today, rumor is a tool of hegemony, and disrupted continuity is the default setting of the infinite scroll. The “FRONT LINE WEAPON” is everywhere leveled against us. In the hands of its modern-day heirs—hyperpop bands and remixers, game-hacking media artists, copypastas—the technique is used to reflect reality, rather than intervene in it. Maybe the scissors were the important part after all—key to the provocation of the cut-up was its intimation of violence to and rupture of the dominant continuity. But when the present is already so thoroughly cut up, it will take a different form of transgression for the future to leak out once again.

- Nigel Krauth, Creative Writing and the Radical: Teaching and Learning the Fiction of the Future (Multiningual Matters, 2016), 118. ↩

- Barry Miles, El Hombre Invisible (Virgin Books, 1993), 118. Cited in Rob Bridgett, “An Appraisal of the Films of William Burroughs, Brion Gysin, and Anthony Balch in terms of Recent Avant Garde Theory,” Bright Lights Film Journal, February 1, 2003. ↩

- I. Q. Hunter, British Trash Cinema (British Film Institute, 2013), 124. ↩

- From a Q&A at the Jack Kerouac School of Disembodied Poetics at Naropa University, July 20, 1976. ↩

- Antony Balch, “Interview,” Cinema Rising 1 (April 1972). Cited in Hunter, British Trash Cinema, 124. ↩

- Jamie Russell, “Guerilla Conditions: Burroughs, Gysin and Balch Go to the Movies,” in Retaking The Universe: William S. Burroughs in the Age of Globalization, ed. Davis Schneiderman and Philip Walsh (Pluto Press, 2004), 168. ↩

- Tony Rayns, "Fear and Loathing in the Cinema," Time Out, 1975, cited in Russell, “Guerilla Conditions,” 169. ↩

- William S. Burroughs, “Origin and Theory of the Tape Cut-Ups,” lecture delivered at the Jack Kerouac School of Disembodied Poetics at Naropa University, July 20, 1976. ↩

![‘I’ve Got 8 Chickens at Home Counting on Me’—Delta Pilot Calms Nervous Cabin With Bizarre Safety Promise [Roundup]](https://viewfromthewing.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/delta-cabin.jpg?#)

.png?#)