Sinners review – links the past and present with music and blood

Finally free from the Marvel machine, Ryan Coogler delivers the goods and then some with his music-powered, genre-splicing latest. The post Sinners review – links the past and present with music and blood appeared first on Little White Lies.

It feels a little odd to reflect on Ryan Coogler’s career at this present moment and realise that the director has been locked into franchise filmmaking for a decade. Perhaps it’s because of how clearly his voice has come through even in legacy works like Creed, or amid the stifling weight of corporate synergy that comes from Black Panther. His new work, Sinners, feels like a filmmaker liberated: Coogler’s first original screenplay since 2012’s Fruitvale Station, and one bursting with ideas in its bloody, anarchic reflection on a history of black culture and artistry (and its continual appropriation).

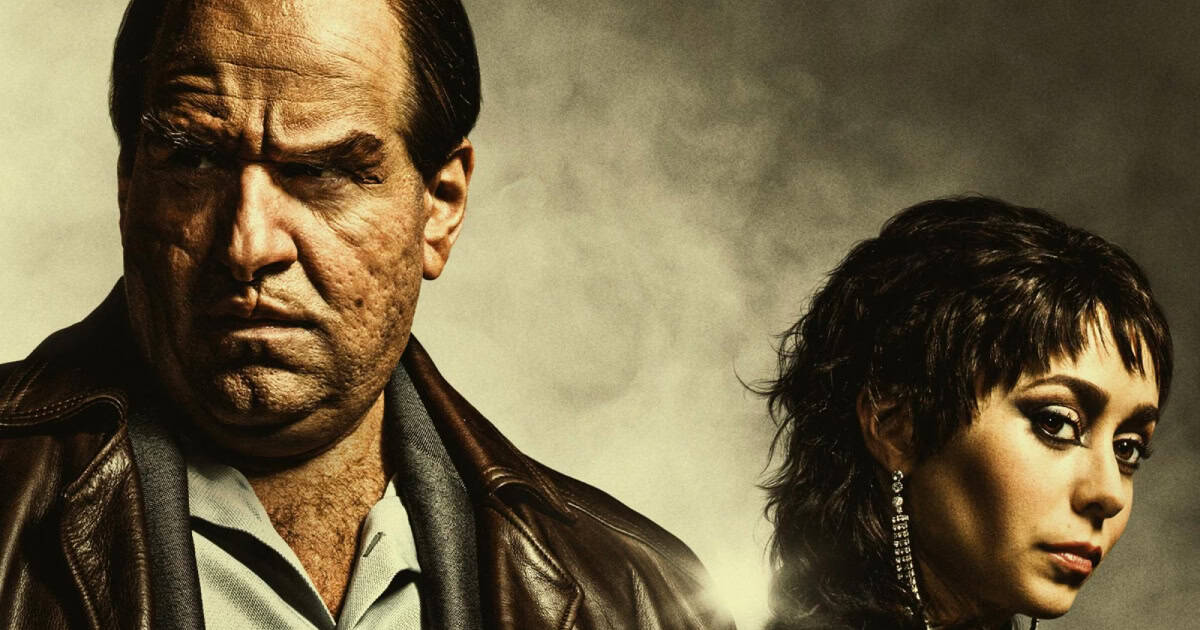

Set in 1930s Mississippi in the midst of Jim Crow and Prohibition, Sinners opens on a bloodied and terrified guitarist fleeing to the sanctuary of a church, clutching the neck of his broken instrument. He’s ordered by the preacher, his father, to give up his ‘sinning’ ways and put it down. Coogler cuts away before we see the decision made. One day earlier and everything is (relatively) fine, as Samuel is reconnected with his cousins, an infamous pair of local gangsters known as the Smokestack Twins (one is called Smoke, one is called Stack, both are played by Michael B. Jordan).

The two – separated by their red and blue ties and hats – have bought an old sawmill to convert into a juke joint, a rare communal space for African Americans living in this time. While this writer isn’t qualified to speak on the quality of southern accents, both iterations of Michael B. Jordan are magnetic, Coogler iterating on the actor’s fiery charisma by driving the twins down separate paths. For a time, though, he isn’t actually the entire focus, with much of the film focusing on Samuel navigating this other world of liquor-fiends, gangsters and maverick musicians. This naive boy is confronted with desires of the flesh that are a far cry from his father’s quiet, neat church.

And so begins a rushed operation to get the juke joint open by the evening, with Samuel recruited to play some live blues music along with charming drunk and musician, Delta Slim (Delroy Lindo, providing incredibly well-timed comic relief). Other than the warning at the film’s opening about music as a kind of magic ritual which can summon spirits, bring healing to communities and attract evil, Sinners is played straight as a period piece for a surprisingly long while.

Coogler’s work has always been patient even within the maelstrom of franchise spectacle, but the first half of Sinners is even more deliberate than before. His script roams among its wide cast, taking its time to add detail to the characters’ lives and expand the lay of the land, examining a tight-knit community of immigrants, displaced people and outcasts who gradually filter into the purview of Smoke and Stack.

Coogler’s eye, via DoP Autumn Durald Arkapaw (a collaborator on Black Panther: Wakanda Forever), is more trained on the immigrant and displaced communities of the time; many of the white characters in the film remain far in the background for a lot of this time, quite literally out of focus. The changes between large format IMAX photography and conventional 16:9 feel calculated rather than random, timed to stings of music or deliberately prying the frame open.

That might sound distant and analytical, but Sinners moves at a satisfying rhythm and weaves passionate conflicts as well as levity throughout this quieter first half. That could be in a sharp cut from Delta Slim being told about all the beer he can drink as payment, to him gleefully playing the harmonica in an impromptu street performance. Or in how a conversation between Wunmi Mosaku’s Annie and one of the Smokestack twins turns from spiritual connection to connection of a more physical kind. This is to say that while Sinners never makes light of the history of the south, it’s not at the cost of the fun that can be had with this crossover between blues players, drinkers, and vampires. Its reflections on marginalised communities are in part communicated through sex, big blood squibs and gnarly prosthetics, foot-stomping musical sequences, visual gags and even a gunfight, this well-honed carnage almost overpopulating the film’s second half.

Without giving the game away, as the film melds more with the horror and the viscera of Carpenter-esque genre pieces (Coogler has repeatedly cited The Thing and Salem’s Lot in the lead up to the release) it begins to shift to something more playful and fluid. The shift is marked by an audacious single take sequence shot in IMAX, swooping through the juke joint. The details are best witnessed rather than read here, but as the musical sequence takes hold, Sinners abandons realism in a strange and bold collision of anachronisms, with music becoming a ritual which connects people not just across space, but across time as well. There’s more than one dance sequence, each more wild than the last (I’m not sure I’ve ever seen a group of vampires doing an Irish Jig).

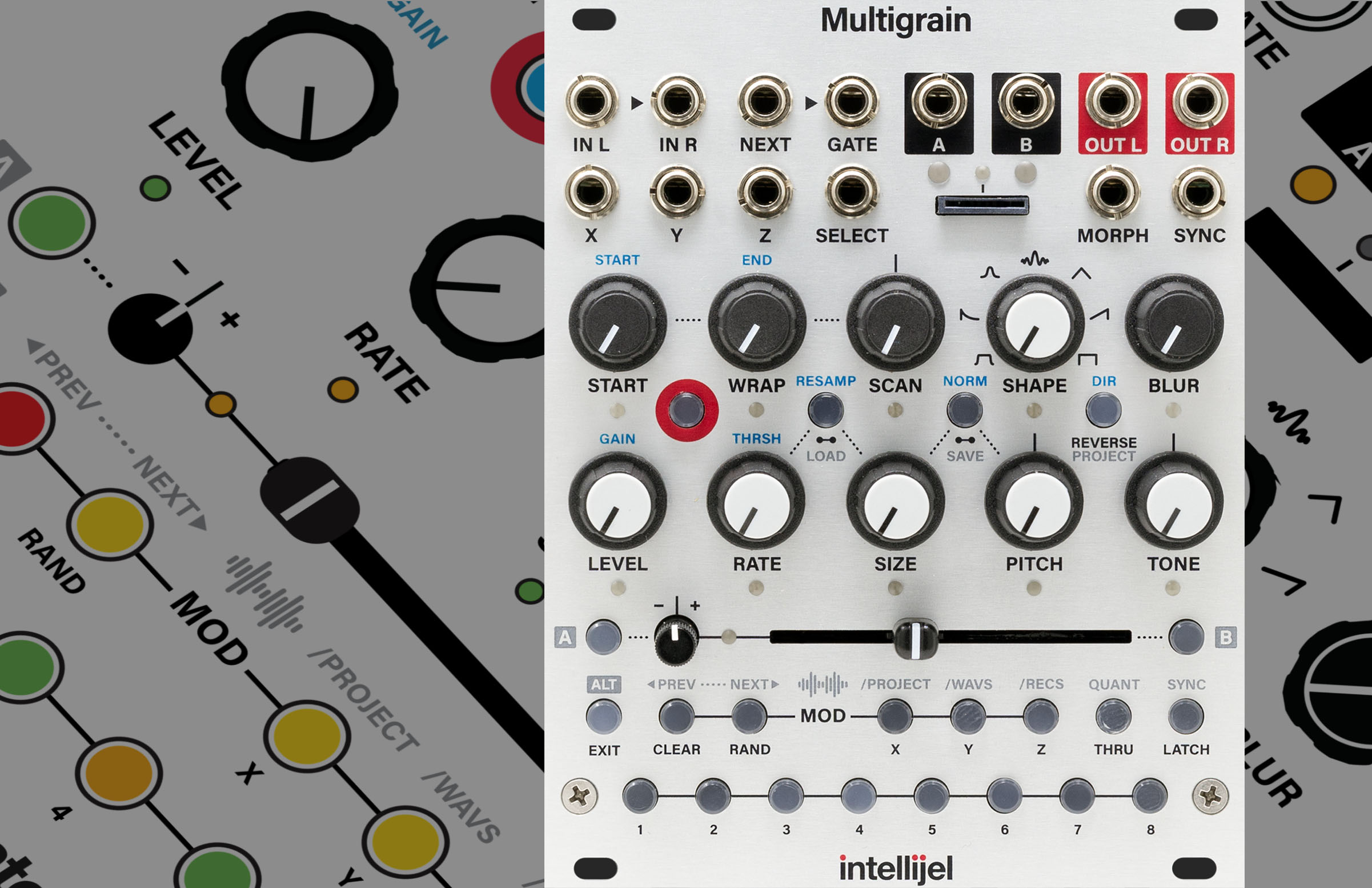

The eventual turn to its riotous second half is underlined by a typically inventive soundtrack from Ludwig Göransson. The multifaceted score begins with blues guitar playing as a base before subtly layering other styles of music over it. Compared with what’s to come, it comes off as formal restraint, with something supernatural simmering just below the surface through uncanny instances of sound design. Sometimes, though, there’s fun in being less subtle, and the director and composer indulge with the introduction of the vampire Remmick (Jack O’Connell), his arrival announced with the crash of drums and heavy electric guitar, the presence of which feels as unnatural as the demonic entities we’re watching. The film’s visual idea of the vampire is simple but fun, mostly normal in appearance other than an uncanny glint of light in their dark eyes – using this subtlety to stoke paranoia in the increasingly confined sawmill.

These two halves sound strikingly different, but it never feels like a completely bifurcated film: you can’t have one without the other. The sense of harmony and shelter that Coogler cultivates in the first half is in order to blow it up in the second, perhaps so the audience can share in the film’s rage and grief at how such spaces are invaded. The film as a whole does strain a little bit under the weight of these ideas, and the story runs surprisingly far into the end credits as it puts a button on what the past means to us now.

But regardless, there’s elation in seeing these musical performances and seeing Coogler free to play with technique and tackle political ideas in a manner that’s been constrained under the Marvel machine, for a time. Sinners elegantly walks a line between enjoyable mayhem as well as a sense of tragedy around this safe haven being ripped apart – but also leverages the classical allure of the vampire for motivations inspired by its reflective first half. You can see the temptation: of a prolonged life in a time and place where security is never guaranteed as well as the power to live free of the repression of the church and the oppression of white hegemony, without fear of demonisation from either.

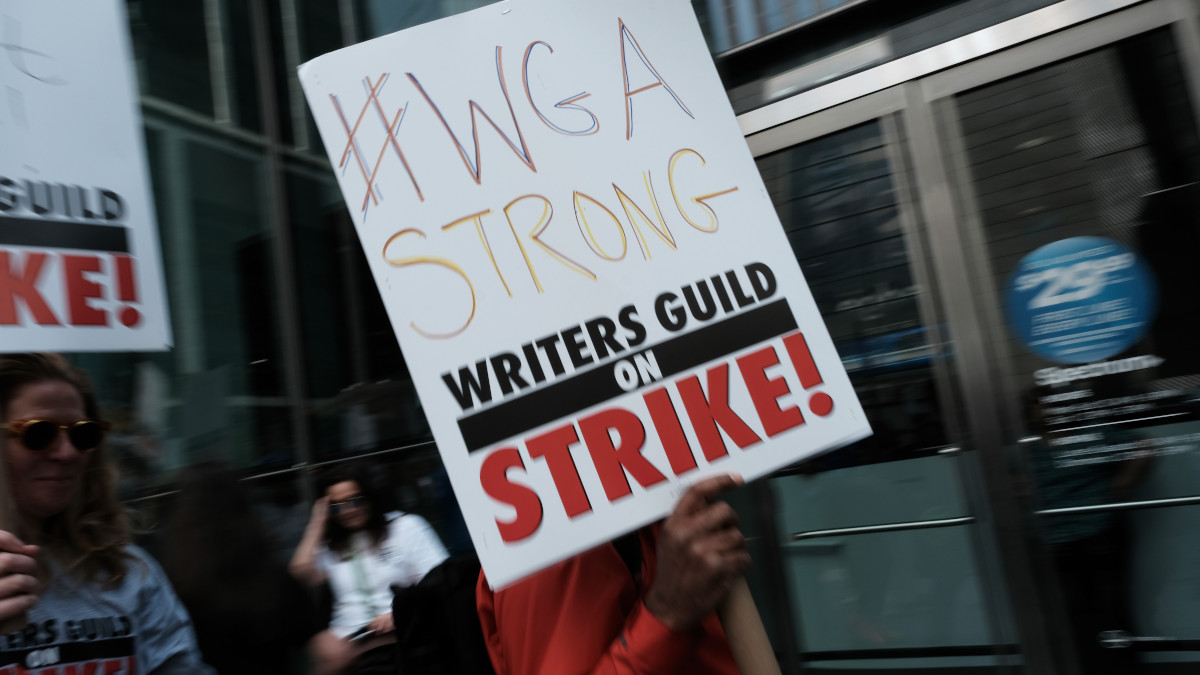

There’s a discussion of the contradictory drives of American segregation – a dehumanisation of anyone deemed undesirable, coupled with an envy of their culture. Delta Slim puts it plainly: “White folks like the blues just fine, they just don’t like the people who make it.” In this context, vampires were always going to be some kind of allegory relating to Jim Crow, but here they’re also evocative of a long-standing parasitic relationship between music pioneered by Black artists and white opportunists who take the chance to separate the sound from its origin. In that sense, having to work under this kind of system really does feel like a devil’s bargain – and though Sinners isn’t so simple as to have a correct “answer” to its take on vampires, it’s exciting to see the many ways in which Coogler presents the industry as something feeding on the blood of its artists.

ANTICIPATION.

His previous film felt underwhelming, but it’s exciting to see what the man who made Creed can do outside of pre-established franchises.

3

ENJOYMENT.

Ryan Coogler’s Thriller?

5

IN RETROSPECT.

An ambitious film which links the past and present with music and blood. Maybe the most “one for me” a post-Marvel Studios work a director has had to date.

5

Directed by

Ryan Coogler

Starring

Michael B Jordan,

Miles Caton,

Jack O’Connell

The post Sinners review – links the past and present with music and blood appeared first on Little White Lies.

![‘I’ve Got 8 Chickens at Home Counting on Me’—Delta Pilot Calms Nervous Cabin With Bizarre Safety Promise [Roundup]](https://viewfromthewing.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/delta-cabin.jpg?#)

.png?#)