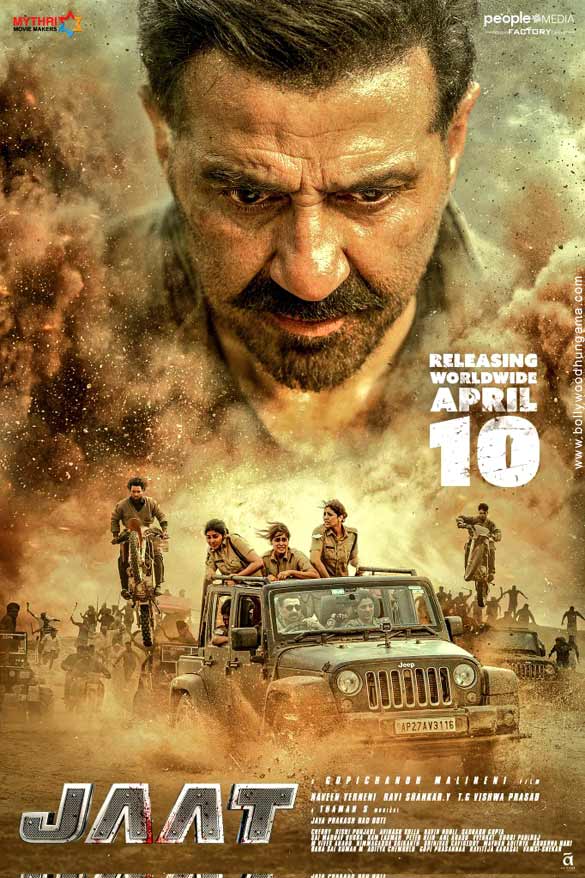

Total Fidelity: Alex Garland and Ray Mendoza on “Warfare”

The writers and directors talk about bringing a Navy SEAL's real-life story to screen without a shred of fictionalization.

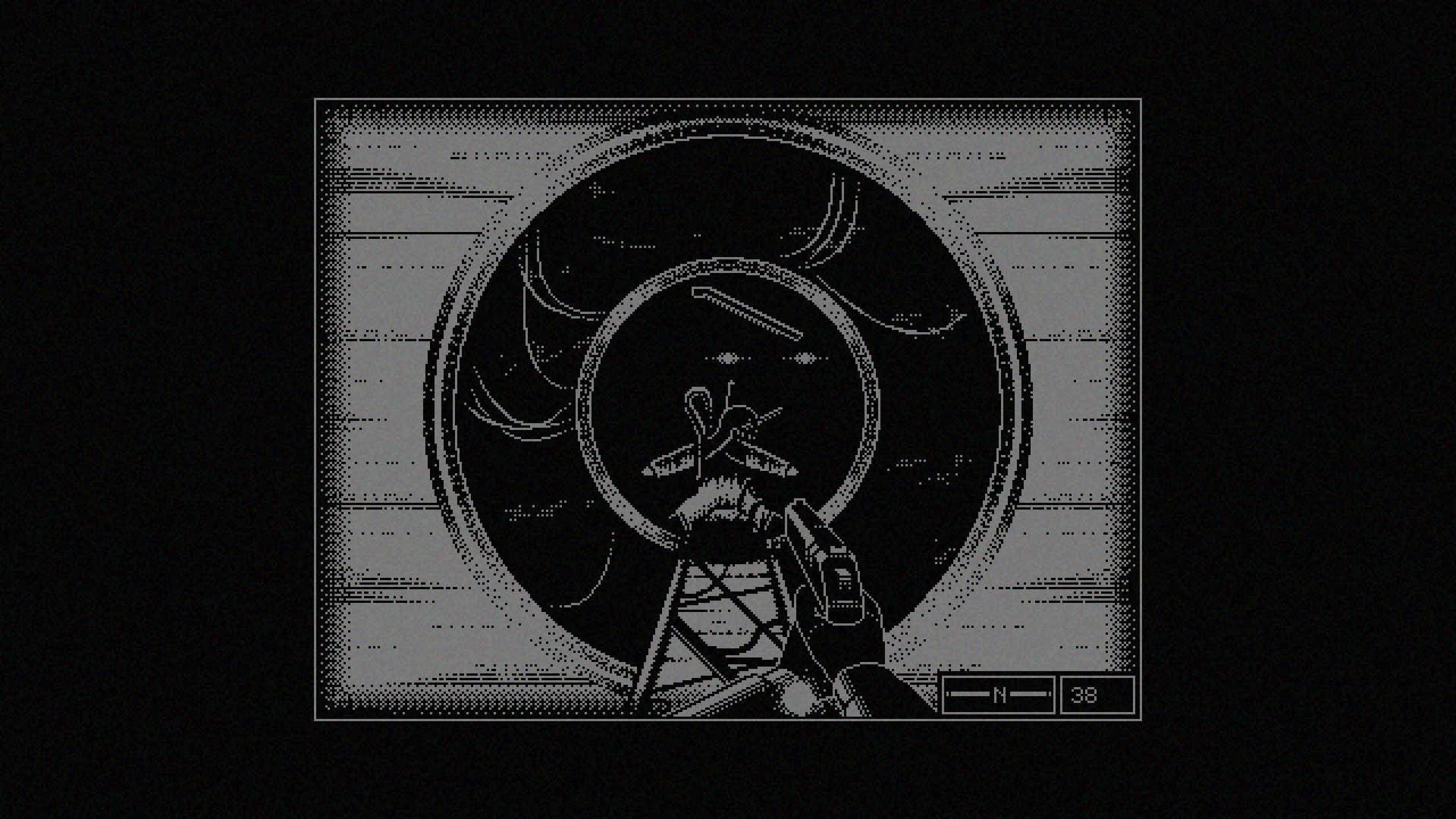

Alex Garland’s worlds, even those in the more fantastical realms of “Ex Machina,” “Dredd,” and “Annihilation,” find as many ways as possible to sell their fantasies within a realm of muted, grounded realism. And so it goes that his latest project, “Warfare,” takes that zeal for verisimilitude to its grandest degree yet: Recreating a real life incident during the Iraq War in 2006, dramatizing the events in real time to the best of its participants’ recollection. (Text at the film’s opening reads: “This film is recalled from their memories.”)

The incident itself, a terrifying operation in which a group of American Navy SEALs came under fire in Ramadi Province while occupying a civilian building, came to Garland courtesy of former SEAL and current military consultant Ray Mendoza. He’d met the man on the set of his last movie, “Civil War,” coordinating the realistic troop movements for that film’s ear-smashing raid on the White House. While there, Garland asked Mendoza if he had a story to tell; the latter told the former about this event, and the pair chose to co-write and direct an adaptation of this story. The quest to recreate this event, warts and all, became “Warfare.”

The results are staggering in their immersiveness: Long, theatrical takes let each agonizing second of the team’s overwatch shift go by in real time. In fits and starts, we see little moments that let us in on the inner lives of the unit, played with unfussy proceduralism by a murderer’s row of young talent (Will Poulter, Charles Melton, Cosmo Jarvis, Joseph Quinn, Michael Gandolfini; “Reservation Dogs“‘s D’Pharaoh Woon-A-Tai plays Mendoza), who all worked themselves to the bone for three weeks, training and bonding as a unit to sell the immediacy of their teamsmanship.

Then, after half a movie of waiting, an IED splits the characters’ (and the audience’s) ears, and “Warfare” hammers home the visceral unpredictability of combat: The bureaucratic and process loops that kick in once training takes over, the ways in which that training can fail even the most stalwart warriors, and the misty unknowability of where your enemies are and where they can strike next. All of this proceeds without a shred of film score or non-continuous editing; besides David J. Thompson’s steady, structured cinematography, you’d be forgiven for mistaking “Warfare” for a documentary.

Leading up to “Warfare”‘s release in theaters on April 11th, Garland and Mendoza sat down with RogerEbert.com to talk about the moment they chose to tell Mendoza’s story, the power of sound design, and whether you can truly capture the boots-on-the-ground feel of war on screen.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

I remain so curious about the origin story of this project, which stemmed when the two of you worked together on “Civil War.” What was the moment when you guys decided to make a film about [Ray’s] experience?

RAY MENDOZA: I think that moment started when [Alex] asked if I had a story to tell from that time. There’s a lot of stories we know over a twenty-year war; I know a lot of Rangers, Green Berets, Marine Corps. So I asked myself what story I’ve always wanted to tell. And I had to really ask myself if I was ready to tell it.

Furthermore, I had to ask my friends if it was okay, because I would need their help. Once I knew that support system was there (because I knew I would need it), I pitched it to Alex. I told him the whole story, and I think it fit the mold we needed it to. Some trust was already there, so we decided to do it.

As co-writers and co-directors, what was the division of labor there? Alex, how much of your perspective was putting your stamp on Ray’s story, versus using your experience and filmmaking tools to facilitate Ray telling it himself?

ALEX GARLAND: I had a kind of separate motivation, which is the reason I asked Ray if he had a story he wanted to tell: I wanted to make a war film in which war was treated as accurately as you could possibly do it. That was the challenge.

Originally, I said to Ray that, in order for this to work, we need approximately an hour and 30 minutes, hour and 40 minutes of an incident. We can slide a window around within that, but we can’t expand or contract it. If there are five minutes where nobody said anything, what’s the camera gonna do? The goal was total fidelity.

So from that point, I ask Ray if he’s got a story, he says, “yes, there’s a story I want to tell, and I feel comfortable working on this story.” At that point, my job stops being a writer in a traditional sense; I become like a recorder. It’s co-writing, because I’m not contributing any part of this story.

One of the rules we set was that nobody can subtract anything from the sequence of events or add things that weren’t there. They can say, “this is what happened,” and nobody who wasn’t there is allowed to do that. That included me. So as a piece of writing, the possession of the sequence of events and the dialogue, all the things you would normally attribute to a writer, really belong to Ray. All I did was structure it as a screenplay, which is a completely different, sort of technical job.

Then Ray and I interviewed many other people involved in this incident, and we would fold that into the screenplay. We’d work out where things were, how two separate but concurrent actions could coexist.

There’s an interesting effect that has, where you’re telling this true story with as much alacrity as possible, to see whether there’s an innately cinematic quality to that.

AG: I knew there was. I just think reality is interesting. When I was pitching this to A24, I said, “I think this approach would work if it were two people in a kitchen talking about getting divorced.” If you were somehow able to precisely recreate the hour and a half conversation in that kitchen, I think that would be pretty dismaying to watch, but probably quite compelling. I never had any doubts about that.

My real concern, and eventually those of the cast and crew we put together, was whether we could do justice to the thing Ray and his colleagues are offering. Ray and I would talk about how nervous I was about whether I would deliver on my side. I usually never worry about that; I probably should. But in this case, it was different. There was an enormous sense of responsibility we felt to Ray and the other guys.

Ray: What was it like revisiting these events, both with Alex and your former squadmates?

RM: It’s a bit of an emotional rollercoaster. There are obviously these very emotional, powerful moments, life-changing moments for me. Recreating them, digging into those deeper feelings of…. it’s not easy to admit that you were terrified, at least being a SEAL, in our culture. At least when you’re young. So it’s having to discuss those things and convey that to D’Pharoah.

But there were also rewarding parts of it; I’m so proud of these guys, even when you see them do these very complex movements, shooting blank rounds in close proximity, flowing and predicting each other’s moves. There are proud moments and sad moments. It’s this feeling of almost looking back in time, looking at myself and younger versions of all my friends. Smiles and cries, right?

I presume the other guys felt the same way about allowing their stories, in all of their vulnerabilities, to be told. I think specifically of the character Will Poulter plays, where he experiences a moment of shell-shock and has to defer to his fellow commander [played by Charles Melton]. There’s an honesty in that vulnerability, admitting that the experience incapacitates you.

RM: No one’s perfect, you know; I’ve done a lot of training and instructing for SEALs and actors alike, and it applies to a lot of industries, even the movie industry. Mistakes are going to happen. It’s inevitable.

What separates good production units or military units is, when mistakes happen, it all goes back to preparation and training. How fast can you get back on track? A mistake happens. Adjustments happen. Leadership makes decisions. Boom, we’re back. If you make a mistake, you’re off track. Make another mistake, we’re off track. Now it takes twice as much effort to get back on track.

On that day, there were a lot of things going wrong, but we were constantly fighting to get back to that line. That’s what I wanted to show: not the perfect heroes fighting with big score behind them. It’s not that. It’s us fighting constantly to get right back to that line. That’s what I wanted to showcase.

I’m really curious about the craft of it, too, because you mentioned the lack of score, which lets the sound design do so much of that aural heavy lifting. How did you work with the sound team to build that immersive soundscape?

AG: The lack of score was a no-brainer. It would have been weird, putting music in this. It would have felt crass and intrusive. I think the sound design team—this guy called Glenn Freemantle, I’ve worked with him for 25 years—is just really good. Of course, film is collaborative; I want to stress that above everything else because it’s so often not presented or seen as such. In this case, the primary sound design collaboration carried some abstractions that were sort of hearty. But one of the things about this film’s sound design that makes it work so well is this incredible precision when it comes to the sounds of battle. Ray and Glenn worked closely on that: Not doing the kind of tricks that we often employ in movies (add some sub to a gunshot to make it slightly sexier), but just aiming for fidelity.

Glenn had just come off the back of “Civil War,” which had some battle sequences where he had a chance to really think about the soundscape. Here, it had some crucial extra refinement from Ray, bringing this deep, complex, firsthand understanding that brings it to another level.

It makes it even more important as a tool to establish perspective in space, too. Think of the IED that goes off halfway through the film, in which everyone has to spend the next few minutes getting their bearings. You use sound really smartly to gauge who is where, who has been affected in what ways by the explosion, etc.

AG: There is that showy stuff, and it’s crucial. And the soundscape after the IED goes off is something people will notice. I often thing that what sound designers do is not notice. But I notice it in stuff like, when the grenade goes off, twenty dogs in the neighborhood start barking. People may or may not notice that, consciously or unconsciously, but it is a thing that happens. You’re lying in bed, and there’s a car crash outside, and all the dogs go crazy, right? That gives it this little quality of truth and depth. And of course, because there’s no music, there’s nothing to hide behind. It’s front and center the whole time.

Speaking of collaboration, I imagine the cast had to go through a process where they had to form a similar brotherhood while prepping and shooting this film. What did you two and the other squadmates do to take them through that, and what was it like seeing them bond through the course of production?

RM: It’s full immersion, really. I’ve found that the weapon stuff is the easy part: I can take someone from A to Z version relatively fast. But two things I wanted them to take away from the film and really experience was the genuine brotherhood, and the leadership of Will, Charles, Joe Quinn. It was more about the experience off set for me. They were going to have to use that, and it needed to be really genuine.

So we created this environment where they would work out and stay in this hotel in the middle of nowhere. There were no distractions other than that. They had to be with each other. I gave them the expectations of working out every day, staying fit and focused. So they would go out, eat, work out together. They’d all ride to set together, get dressed together. They did everything together. Even off set, when they weren’t on camera, you’d see them out back joking and doing weird shit. That’s them just having fun with each other, which allows them to be able to predict each other’s movements. If somebody’s falling short that day, they step in and pick each other up.

That was more important to me than the picture. The portrayal is obviously important for them; the process was built for them, and the rest of it—the character, their relationships—will follow. I told them to find their best friend in the platoon; find that guy, and they can now use that. Imagine this guy gets his fucking legs blown off.

Speaking to that moment, I was really struck by that introductory scene, which has to do a lot of economical storytelling to establish the unit. This is just about the only time we see their full faces, and we don’t know about them yet. But we see how they interact with each other as a unit, in a very irreverent context we won’t see for the rest of the film.

AG: Ray had this bit of music. I think he first talked about ending the movie with it, but the way he explained it, one of the guys used to show this group the film every time they went on an operation. Once we knew that, we weren’t exactly duty-bound to put it in, but it became a perfect way to start the film. I listened to the music and we talked about it; one morning meeting with our DOP Dave Thompson, phenomenal guy, and Allon [Reich] the producer, we sat around and thought, “Hang on, this could work. How do we do it? What do we need to build?”

We didn’t have permission to use the music at that point, we just decided to shoot it and get permission later. Ray did this lovely thing where he gave the cast three modes to be in—quiet, medium, and then really go for it. That was a lovely day.

So Ray, in the real-life context, what’s the goal of hyping up the team like that?

RM: This was 2006; we didn’t stream movies. Everything is a hard copy. So it was just this video that all of them are looking at. There’s a hard drive being passed around; there’s tons of other videos, but it was just a good song. We all wanted to be that dude in the music video. It just allowed us to be kids; we’d be dancing, and it was just all right. It became a tradition.

AG: It’s lovely, because it shows them partly as boys. We work with this incredible editor called Fin Oates, she’s a lovely person and a fantastic editor. The only thing she had a problem with was the video, because she has a kind of younger, more enlightened sensibility on the video itself. But once she clicked into why it’s there and what it is, she really got behind it. I thought it was a beautiful addition. We were permitted to do it because it happened.

But if you’re looking at it in pure film terms, it’s such an elegant way of introducing us to this group of young guys and giving us tiny bits of information. How are they reacting? Are they smiling? Are they slightly detached? They fully involved? Are they gearing everyone up and leading the cheers, or hanging back? and so on.

Ray, what do you hope people take from this, in terms of our views of servicepeople and the conflicts in which they’re serving?

RM: There are a lot of war films about there, and they can all be great. But this is totally from my perspective. What I want people to start to understand, if it becomes a conversation piece, where these guys are coming from. There’s a lot of crazy stuff going on right now, and they’re being asked to do these things that are changing their lives.

There are people who don’t have the vocabulary yet, and those who want to know. So hopefully, it could be a bridge for everyone: active duty, veterans, loved ones, family, friends. If you have a friend in the Army who’s coming back, you can watch the film and see the kind of things he could have gone through, and have a conversation.

![The Top 10 “Invisible” Movies of All Time (We Think) [Halloweenies Podcast]](https://bloody-disgusting.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/invisible-movies.jpeg)

![THE NUN [LA RELIGIEUSE]](https://www.jonathanrosenbaum.net/wp-content/uploads/2019/12/TheNun-300x202.jpg)

![Bright Spots in the Darkness [My 1998 Top Ten List]](https://jonathanrosenbaum.net/wp-content/uploads/2009/04/rochefort.jpg)

![Courtyard Marriott Wants You To Tip Using a QR Code—Because It Means They Can Pay Workers Less [Roundup]](https://viewfromthewing.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/tipping-qr-code.jpg?#)